Dec 16, 2021 | Alumni, Demography, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Fanni Daniella Szakal, 2021 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Can we lift people out of energy poverty while simultaneously reducing carbon dioxide emissions? 2021 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant Camille Belmin tried to tackle this seemingly contradictory issue by including fertility in the equation and estimating the conditions where an increase in energy access would reduce demand through decreasing population sizes.

© Photopassion77 | Dreamstime.com

About every third person in the world today doesn’t have access to clean cooking fuels and 1 in 10 are without electricity, predominantly in the Global South. Increasing energy access will not only improve the quality of life for many, but it will also propel us towards achieving some of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) such as SDG3, Good Health and Wellbeing, and SDG7, Access to Clean and Affordable Energy.

The downside of increasing energy access is the surge in carbon dioxide emissions that will likely follow. Although populations with low energy access emit only a small share of global carbon emissions compared to countries in the Global North, an increase in energy provisioning would still put more pressure on the climate crisis. But, what if we could increase energy access and decrease emissions at the same time while tackling a few more SDGs in the process, such as SDG5, Gender Equality and SDG13, Climate Action?

Camille Belmin, a participant in the 2021 YSSP aimed to do just that. As a PhD Student at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and at the Humboldt University of Berlin, Belmin focuses on the relationship between energy access and women’s fertility. In a previous study covering 43 countries around the globe, she found evidence that higher access to electricity and modern cooking fuels was associated with women having fewer children.

“With more access to energy, instead of, for example, picking up firewood for many hours a day, women are able to spend more time on education and employment. Energy access also lowers the need for child labor and reduces child mortality through reduction of indoor air pollution and improved healthcare. This often leads to women becoming more empowered and gives them agency over their reproductive choices, leading to a fertility decline,” says Belmin.

In her YSSP project, Belmin took the energy-fertility relationship a step further: she wanted to explore if an initial boost in energy access could lead to a decline in energy demand in the long term through reduced population sizes, both increasing the quality of life and reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

“I hope that by showing that universal access to energy can also have benefits for sustainability, I can encourage investments in modern energy access in countries where basic services are lacking,” she notes.

To find out under which conditions increasing energy access will lead to a decrease in energy demand, Belmin used a microsimulation model of population projection. Under different energy access scenarios, the model follows each individual in a hypothetical population through life events, such as birth, death, and gaining access to education and electricity, while calculating their total energy consumption. She hoped to find a scenario with net savings in energy demand, in other words, a scenario where the more you give, the more you get.

Setting up the model was a new challenge for Belmin ̶ while many scientific fields have been using microsimulation for a long time, applying it to population modeling based on energy access is a novelty. The potential benefits and positive implications of the work were however well worth the difficulty.

The study focused on population simulations in Zambia, where Belmin collaborates with an NGO that aims to finance education for girls through carbon credits, building on the idea that education will lead to lower population sizes and decreased emissions in the future.

“Because of patriarchal structures, women are often bound to household chores, making the lack of energy a huge burden,” says Belmin. “This research is very important to me as a woman, or just as a human, as it seems that providing modern energy services might be a way for women to have more choice and freedom in their lives.”

Further information:

Belmin, C. (2021). Introducing the energy-fertility nexus in population projections: can universal access to modern energy lead to energy savings? IIASA YSSP Report. Laxenburg, Austria: IIASA [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17688]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 18, 2021 | Climate, Climate Change, Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Marina Andrijevic, researcher in the IIASA Energy, Climate, and Environment Program

Marina Andrijevic tackles some inconvenient but fundamental issues around climate change adaptation.

© Lio2012 | Dreamstime.com

Anyone who followed climate-related headlines this summer would have noticed a more than usual amount of talk on climate change adaptation. As it goes with sudden epiphanies in aftermaths of humanitarian disasters in our Western realities, this time we’ve come to realize that we need to seriously think about doing some adaptation.

To be fair, the realization that adaptation is inevitable has for a long time been somewhat of a taboo in the “woke” climate policy and activist circles (the author of this blog is a millennial and would like to acknowledge that the reader’s idea of a long time in climate policy might be different). Admitting that there might be no other option but to adapt to whatever the locked-in effects of climate change are, is arguably defeatist and gives in to the notion that mitigation alone won’t cut it.

While this might be yet another depressing but accurate reflection of the reality under climate change, portraying adaptation and mitigation as different but equally urgent actions could set a dangerous trap if it produces ideas such as: if we adapt enough, perhaps our economies and energy systems won’t need to change so much.

Even if it would be enough (which it wouldn’t), adaptation will not necessarily just happen once we recognize it needs to be done, because the needs and abilities for it operate on different time horizons and geographical scales. Many parts of the world that need adaptation will not necessarily be able to take action, so we have to be very careful when we count on it as a solution to climate change.

This is where we must tackle some inconvenient but fundamental issues about adaptation. Climate change research, especially the areas positioned at the “interface” with policy, could play a crucial role here. In this role, it must be very prudent and avoid doing a disservice to decision makers, and even worse, to people affected by those decisions. In other words, the scientific assessments need to be careful when assuming for whom, where, and how adaptation can reasonably be expected.

We tried to illustrate why this matters in our recent paper that looks at the capacity of populations to adapt to heat stress. We used air-conditioning as a popular, albeit not (yet) climate-friendly adaptation option. My coauthors and I understand that air conditioning could well be maladaptation, meaning that it causes more harm than good in the long-run. Adaptation practices, however, it turns out, are quite difficult to measure, while installed air conditioners can literally be counted, which makes them handy for plugging into our statistical models. We contend with access to air conditioning currently being a good enough example of access to adaptation and promise to assess more options in the future.

Our paper shows how the capacities to protect against heat stress vary widely around the world. Like with many other unjust manifestations of climate change, people in the world’s hottest areas also have the least means to adapt. We found that countries with more income, more urban areas, and less income inequality, are also the ones where more people have access to air conditioning.

This does not come as the world’s biggest revelation, but it conveniently allows us to make informed guesses on how access to air conditioning might change in 2050 or 2100. This is possible because the research community has already engaged in a group effort to propose five different futures with regard to GDP, urbanization, and income distribution (in climate jargon: the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways or SSPs).

Coupling the potential rates of air conditioning with the people exposed to heat stress based on projections of climate models, lets us calculate the cooling gap – the difference between people exposed to heat stress and people who can protect themselves against it with the use of air conditioning.

Depending on whether we find ourselves in the best- or the worst-case scenario of socioeconomic development could mean anywhere between two billion and five billion people globally unable to protect themselves against heat stress with air conditioning in 2050. This range only grows with longer time horizons, with Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia being the areas of the world where these differences are the starkest.

We hope that our paper will motivate further investigations of potential gaps in adaptation that point to insufficient adaptive capacity and help to identify the areas and populations most at risk, as well as what additional work needs to be done in terms of socioeconomic improvements before we can reasonably expect adaptation to take place. Our findings on the importance of factors beyond just GDP, suggest that helping communities to build their adaptive capacity doesn’t mean only throwing money at them (although that would make for a decent start!), but international efforts must focus on issues such as eradicating inequalities, supporting smart urban development, strengthening institutions, and providing education.

So, let’s not take it for granted that we will all be able to adapt either now or in the future. Eliminating the causes of climate change must remain the number one policy objective that will help to reduce the need for adaptation in the first place. But number two could be helping communities that have no option but to cope with what’s already coming at them. Highlighting in our research what the implications of different adaptive capacities are for preservation of livelihoods, is a small step towards achieving this.

Reference:

Andrijevic, M., Byers, E., Mastrucci, A., Smits, J., & Fuss, S. (2021). Future cooling gap in shared socioeconomic pathways. Environmental Research Letters 16 (9) e094053. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17411]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 12, 2021 | Climate Change, Evolution, Science and Policy, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Neema Tavakolian, 2021 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant Lyndsie Wszola explores how human interactions with warming freshwater systems have affected the evolution of fish species through the lens of the North American walleye.

© Justinhoffmanoutdoors | Dreamstime.com

The effects of climate change have intensified over the past few years, especially in our oceans, and human based activities contributing to it are now being taken more seriously. While the warming of our oceans is indeed troubling, many forget that freshwater systems are also being influenced, and that this is affecting the growth and evolution of the species that reside in them.

2021 YSSP participant Lyndsie Wszola wants to explore changes in freshwater systems using human-natural modeling systems at IIASA.

© Lyndsie Wszola

Growing up with a conservation officer father, Wszola is a second-generation conservationist. Knowing she wanted to enter this field at an early age, she realized that she had to get into research and academia first. Her main interests while studying at the University of Nebraska have been the interactions between humans and wildlife.

While researching the relationships between hunters and ring-necked pheasants, she discovered an affinity for quantitative research. This curiosity went even further after she discovered literature on harvest induced evolution and mathematical ecology specifically pertaining to fish populations. Together, this initial desire to explore human and wildlife interactions and her newfound interest in mathematical ecology, led Wszola to take a closer look at North American freshwater systems and how we as humans are influencing its ecology. Her research specifically delves into the growth and evolutionary changes seen in the North American walleye (Sander vitreus) – a popular fish in Canada and the United States. The reason for its fame is its palatable taste as a freshwater fish and its status among anglers, making it both a commercially and recreationally fished species.

Walleye was chosen as the subject of Wszola’s research for many reasons. First, walleye, like many fish, are ectotherms meaning that their body processes and behaviors are directly linked to their body temperature, which is in turn directly linked to the temperature of the water. Unlike other fish however, there is already plenty of research and data on the relationship between the walleye’s growth and temperature. This information makes it much easier to simulate the walleye’s eco-evolutionary growth dynamics in the context of human driven harvests in warming waters. Wszola will also be working with very large datasets spanning multiple latitudes ranging from Ontario, Canada down to Nebraska, USA. The datasets include up to six million fish with four million of those being walleye.

“My goal is to model the influence of temperature on fish harvests based on size. Due to their ectotherm nature, we can observe the changes in body size in annual harvests. As waters warm, walleye grow much faster. We also know that intensely harvested fish often evolve to reach maturation at smaller sizes. When coupled with rising temperatures, this relationship between harvest induced and temperature induced evolution can be fascinating, as we now have two sources working together to change the growth evolution of this fish,” she explains.

Due to warming temperatures, many natural resources are at stake with some of the most sensitive being aquatic in nature. Research like this is important as it allows us to look at our relationships with the environment to be able to react accordingly.

“I hope that the research I do yields fascinating enough results so that from a practical standpoint, future fisheries policies can include climate change dynamics in addition to fish and human dynamics,” Wszola concludes.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 19, 2021 | IIASA Network, Risk and resilience, Women in Science

By Raquel Guimaraes, guest research scholar in the IIASA Migration and Sustainable Development and Equity and Justice research groups and assistant professor at the Federal University of Parana in Brazil

IIASA Network and Alumni Officer, Monika Bauer, recently invited me to participate in a genuinely important event hosted on IIASA Connect with the aim of gathering the IIASA community to discuss the gender dimension in research. As a gender researcher, this topic is part of my daily activities, and I decided to focus on the most important findings of my research: gender, disasters, and climate change.

© Raquel Guimaraes

In my talk, I gave an overview of the data relating to gender and disasters. According to the United Nations Development Programme, disasters lower women’s life expectancy more than men’s; moreover, women and children are 14 times more likely to die during a disaster. For example, most of the victims trapped in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina were African-American women and their children.

Given these facts, it becomes clear that gender is an important dimension of disaster and climate change research. Why is that? First, because gender and natural disasters are socially constructed under different geographic, cultural, political-economic, and social conditions and it has complex social consequences for both women and men. They therefore highlight societal, cultural, and religious norms and values, and shape the needs and risks of the affected individuals. Second, because disasters often affect women, girls, men, and boys differently due to gender inequalities caused not only by socioeconomic conditions, but also by cultural beliefs and traditional practices.

In addition to the above, climate change is connected to an increase in the frequency and/or severity of natural disasters such as flooding, heat waves, and cyclones. Disasters will therefore exacerbate existing inequalities and vulnerabilities in communities, since, as already mentioned, they have a wide range of effects for men and women, as well as for youth and children in both developing and developed countries.

Interestingly, the discussion on the intersection between gender and disasters is not new. References to gender as an issue in climate change debates and international protocols on disaster management have been made since at least the 1994 Yokohama World Conference on Natural Disaster Reduction. Since then, the international community has repeatedly called for gender-responsive disaster risk management.

To ensure gender equality and to overcome problems of marginalization, invisibility, and under-representation, gender concerns and women’s issues has been included into mainstream disaster risk reduction policies. Hence, understanding different gender roles, responsibilities, needs, and capacities to identify, reduce, prepare, and respond to disasters, is crucial to promoting effective disaster risk management.

Given the gender dimension of climate change and disaster research, some important questions that come to mind are: Do women really lack power in disasters? Are they really the fragile gender? The answer is: not always. Evidence shows that, despite gender-differentiated vulnerabilities, women and girls are also powerful agents of positive change before, during, and after disasters.

My research on floods, for instance, shows that in Brazil and Thailand, women can be agents of change. Preparedness to natural disasters have been recognized as key in disaster risk management to the extent that local and international actors emphasize the importance of saving lives and avoiding losses, even before the onset of a disaster. If there are different strategies for disaster prevention according to gender, then emergency management agencies and policymakers should account for these differences, ensuring that men and women combine their strengths to maximize preparedness for floods. Through data from two surveys, I evaluated preparedness by assessing several indicators that accounts for the provision of protective items, emergency plans, and the availability of insurance or information. Using econometric models, I found that women play an active role in disasters, being resourceful actresses in times of crises.

Therefore, during the IIASA Connect Coffee Talk I asserted that gender should be integrated as the basis of a complex and dynamic set of social relations in disaster and climate change research. I appreciate the opportunity IIASA Connect gave me to reflect on this issue with colleagues.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 20, 2021 | COVID19, Poverty & Equity, Risk and resilience, Women in Science

By Benigna Boza-Kiss, Shonali Pachauri, and Caroline Zimm from the IIASA Transformative Institutional and Social Solutions Research Group

Benigna Boza-Kiss, Shonali Pachauri, and Caroline Zimm explain how COVID-19 has impacted the poor in cities and what can be done to increase the future resilience of vulnerable populations.

© Manoej Paateel | Dreamstime.com

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought a halt to life as we knew it. We have been restrained in our activities and freedoms, forced to stay indoors at home, to cancel travel plans, and to transfer meetings to an online space, where most of us have also celebrated birthdays and other important life events that should have been in person with our loved ones. These changes have impacted many aspects of our comfort, our social wellbeing, as well as our financial situations, but it has also brought existing inequalities and poverty into the spotlight.

The risks of the pandemic and restrictions following containment measures have been felt most acutely by the poor, the vulnerable, those in the informal sector, and those without savings and safety nets. The suffering of women in the health sector, school children in households without electricity and internet, workers in the informal sector that don’t have the option to telework, crowds living in slums – to name just a few examples of vulnerable groups – have become glaringly visible to all. These people have had to adapt to new rules and conditions when they were living on the edge even before the pandemic.

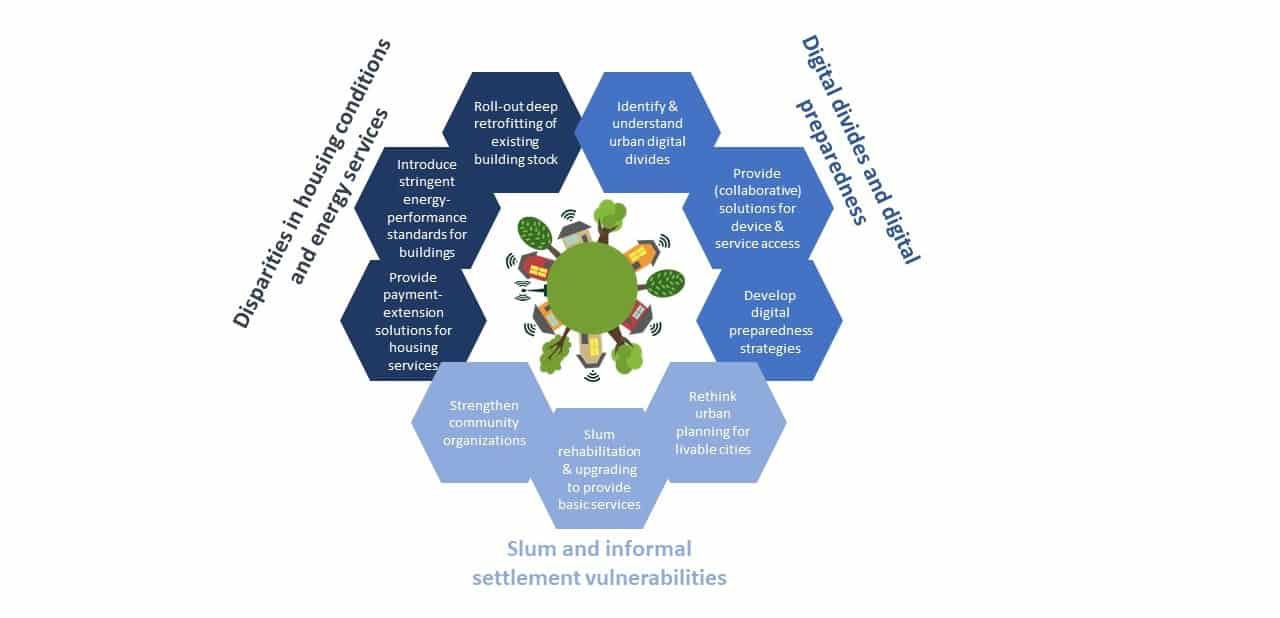

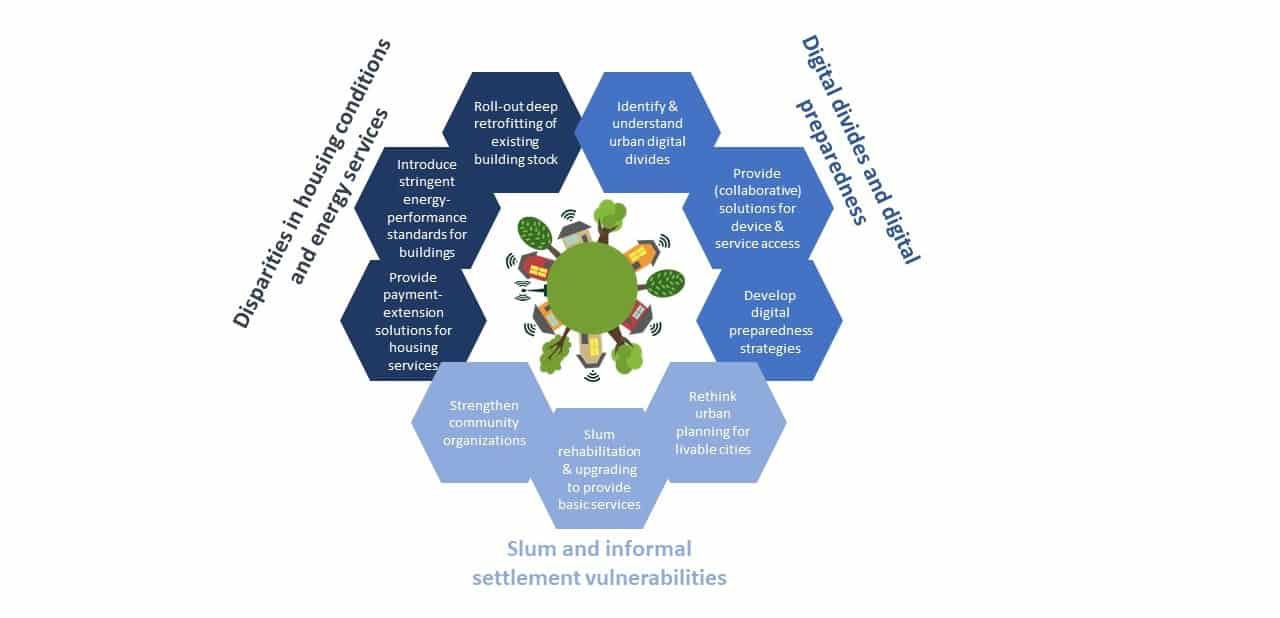

In a new perspective piece published in the journal Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, we explored how aspects related to access to shelter/housing, modern energy, and digital services in cities have influenced the poor and what can be done to increase the future resilience of vulnerable populations.

We described three ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic and related containment measures have exacerbated urban inequalities, and identified how subsequent recovery measures and policy responses could redress these.

First, lockdowns amplified urban energy poverty. Staying at home has meant increased energy use at home. For the poor, who already struggle with utility costs, and typically live in low energy quality buildings, these services have become even more unaffordable. These populations also shoulder a higher burden of poor health, for example, higher incidence of respiratory problems, with poor or inadequate ventilation and insulation increasing their risk of infection even more.

Second, preexisting digital divides have surfaced, even within well-connected cities. Multiple barriers limit digital inclusion: access to digital technologies due to high costs (for devices, internet access, and electricity connections), and unreliable services (again both for electricity and internet), as well as low digital literacy and support. This lack of adequate digital service access is contributing to these populations falling further behind during lockdowns as they miss out on education and income.

Third, slum dwellers in the world’s cities have been particularly hard hit, because of precarious and overcrowded housing conditions, lack of basic infrastructure and amenities, and a high concentration of the socioeconomically disadvantaged, resulting in even more negative consequences of lockdown measures. With many slum inhabitants working in the informal sector, many have been left either without jobs and income, or have been compelled to work in precarious and unsafe conditions to survive. The loss of income has also had knock-on effects, making payments of regular expenditures for rent, water, electricity, and other utility services difficult. Women within these settlements have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, as they are over represented in the informal economy, and more likely to be engaged in invisible work, such as home-based or domestic and care work.

Recovery measures need to ensure immediate relief, but also point towards long-term solutions that contribute to the redistribution of wealth and new urban development, while also increasing resilience to the current and future pandemics or other disasters. There are tested measures that should be reemphasized.

Urban green recovery plans that include large-scale home renovation programs could ensure warm, healthy homes, and affordable energy bills for all. In the shorter-term, alleviation of payment defaults on the rents and utility bills of the energy poor should continue. In parallel, urban digital preparedness, more equal access to the virtual delivery of essential services, and provision of opportunities for virtual working and education for all in the future, need attention.

COVID-19 can be a wake up call to increase efforts to close the digital divide and push for structural change. The crisis has increased the urgency to redesign and improve informal settlements and provide adequate and efficient services that address the diverse needs of poor urban residents. This requires partnerships between urban municipalities, planners, and stakeholders, as well as strengthening local communities for inclusive planning strategies. More immediately, it is necessary to provide direct support to slum and informal settlement populations in terms of income support, adequate nutrition, energy, water, and other basic infrastructure and services.

All in all, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a “test of societies, of governments, of communities, and of individuals”. Digital technologies, home renovation, and slum rehabilitation are the means, rather than the end to improve conditions for all, but if specifically targeted to the poor and most deprived, such measures can reduce inequalities and increase resilience.

All in all, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a “test of societies, of governments, of communities, and of individuals”. Digital technologies, home renovation, and slum rehabilitation are the means, rather than the end to improve conditions for all, but if specifically targeted to the poor and most deprived, such measures can reduce inequalities and increase resilience.

Reference:

Boza-Kiss, B., Pachauri, S., & Zimm, C. (2021). Deprivations and Inequities in Cities Viewed Through a Pandemic Lens. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 3 e645914. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17121]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 10, 2021 | Communication, IIASA Network, Science and Policy, Women in Science

By Marie Franquin, External Relations Officer in the IIASA Communications and External Relations Department

Marie Franquin writes about her first six months as part of the IIASA Communications and External Relations team.

This year has certainly been a great challenge for all of us, migrating our lives online and our offices to the living-room. Last summer, I finished my PhD and was ecstatic to have found a job at IIASA that encompassed day-to-day work on my favorite skills: international stakeholder engagement, policy interface, and interacting with researchers, including early career ones!

All of these aspects were covered in the newly launched 2021-2030 IIASA Strategy that was published in the winter. My challenge remained to know how I could best apply my science to policy and research skills to contribute to these goals. How do I help a systems analysis research community move towards more impact and increasing stakeholder engagement?

It quickly became obvious that my position in the external relations team required multitasking and honing a series of skills. The first and top skill that I have kept developing for the past six months was interacting with international stakeholders from all over the world, which included not only our National Member Organization (NMO) representatives and researchers from these countries, but also IIASA researchers and alumni. Working at IIASA I have already gained experience in developing relationships with stakeholders of the research community all over the world.

© Swietlana Malyszewa | Dreamstime.com

The IIASA stakeholder community also sheds new light on the value of the institute’s expertise in systems analysis for building international scientific partnerships, whether it be formal ones with my colleague Sergey Sizov and his science diplomacy expertise, or by facilitating research partnerships between our NMO countries and IIASA researchers.

With my colleague Monika Bauer, I am also learning about the future of stakeholder engagement and how to build virtual communities, like she’s doing with IIASA Connect:

“We are building the global systems analysis network on IIASA Connect. This tool allows colleagues, alumni, the institute’s regional communities, and collaborators to directly engage with each other and take advantage of the institute’s international and interdisciplinary network. It is something completely new for the organization,” she explains.

Our recent partnership with the Strategic Initiatives (SI) Program was aimed at better understanding the IIASA NMO countries and their individual research priorities for the next decades. I learned about local challenges and strengths and how countries have managed to move forward as a nation or by working hand in hand with their neighbors.

Coming from a research background, I am fascinated by the insights I am gaining working with IIASA communications colleagues on how to promote research and its impacts. I particularly enjoyed working with Ansa Heyl, helping IIASA experts build their policy brief submissions for the recent T20 Italy call for abstracts. As part of my skillset and center of interest, I aim to apply my science to policy skills here at IIASA to support the researchers and impacts of the amazing work done across the institute.

Having mostly worked with and for early career researchers for several years, I remain sensitive to their needs for career development opportunities. I am therefore excited to work with colleagues in the institute’s Capacity Development and Academic Training (CDAT) program to further define and support research excellence at IIASA, especially in the very promising next generation of systems scientists.

Few workplaces are so well connected and offer so many opportunities to develop such a broad range of skills as the IIASA Communications and External Relations team. As we are working towards fulfilling the IIASA Strategy’s aim of strengthening partnerships, I look forward to continuing to interact with IIASA researchers and supporting the institute’s goals of making sure the work done at IIASA positively impacts society. So come and chat with me!

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.