Jan 20, 2021 | Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Sustainable Development, Women in Science

By Shonali Pachauri, Research Group leader, Transformative Institutional and Social Solutions

Shonali Pachauri discusses a new framework developed at IIASA to more accurately identify the energy poor.

PowerForAll

Energy is a prerequisite for economic and social development. Today, it is widely believed that there are 840 million people still living without electricity in Africa and Asia, while many more are without access to reliable power. And because of COVID-19, this number is growing again.

But what if this data, which governments and donors rely on to allocate money and shape policy, are flawed? And what if we’re even further from eradicating energy poverty than we think? This is the conclusion of a new framework for counting energy access.

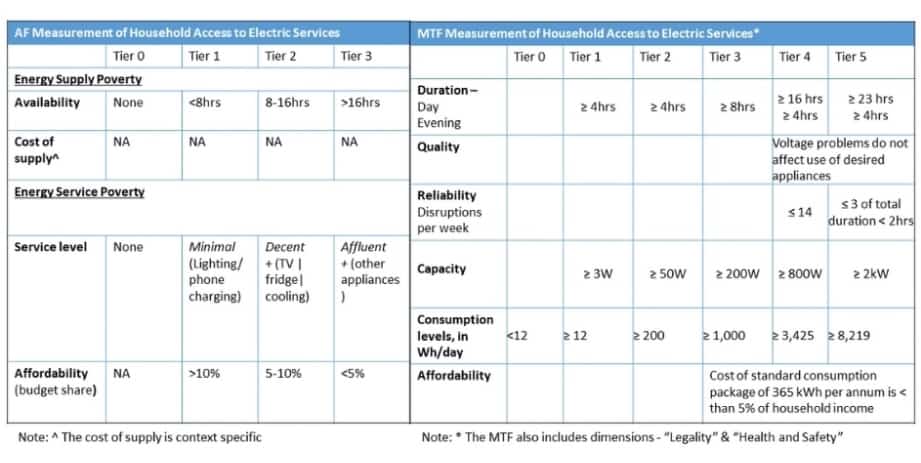

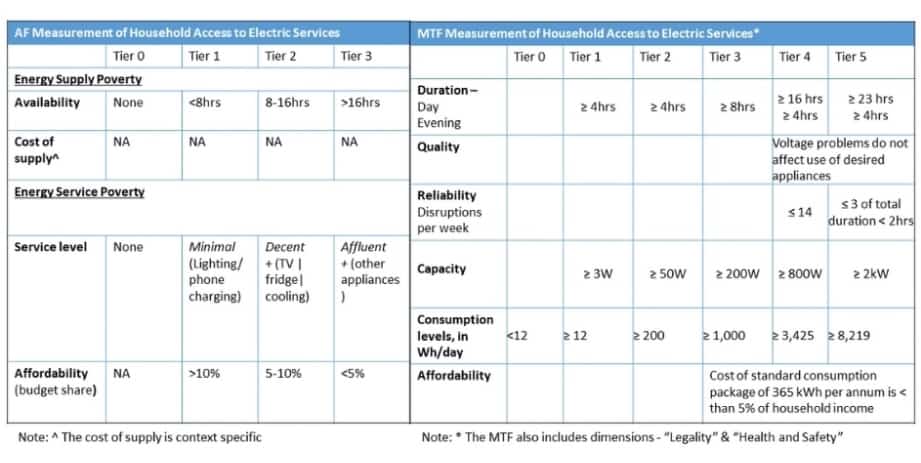

The United Nations uses a simple indicator of the share of population with electricity connections to measure energy access. But this grossly underestimates the number of energy poor, because it considers a household to have access even if they receive irregular quality and hours of electricity supply or are unable to afford anything beyond an electric light.

Recent efforts to improve how we measure energy poverty have made vast improvements but have now resulted in frameworks that are complicated and “data needy”, therefore difficult to scale up to a global level.

A new framework developed by IIASA builds on existing measurement frameworks, but simplifies and advances these to more accurately identify the energy poor. It has already been applied to actual data from Ethiopia, India, and Rwanda to test how well it captures energy poverty in comparison to the World Bank’s Multi-Tier Framework (MTF).

The framework distinguishes between two aspects of access: the quality of power supply and the circumstances of the end-user. This distinction is important to better direct policy efforts where they are most needed, that is, to energy suppliers and/or to households. It also reduces the number of dimensions and tiers to simplify the MTF.

Instead of correlating energy consumption with energy access, a key advancement of the new framework is using ownership of different types of appliances as a proxy for measuring household amenities and services derived from the use of these appliances to improve wellbeing. Electricity consumption is a misleading measure of energy service, because for those who use inefficient appliances, more consumption does not translate into more service. For instance, a household using six inefficient light bulbs is not better off than one that uses three efficient high luminosity light points and an efficient fan that provides comfort from the summer heat. The framework also improves on how affordability is measured to consider appliance purchase costs in addition to recurrent electricity expenditures in assessing the budget share spent on electric services.

When applied to real data, the framework suggests that the energy poor are more segmented than what is reflected by existing binary or MTF indicators. The categorization of households according to electricity consumption differs markedly from that according to energy services and using appliance ownership, revealing greater heterogeneity among the energy poor than what is reflected in the MTF’s consumption-based indicator.

In addition, the new framework shows that affordability is even more of a constraint to gaining access to modern electric services for households in Ethiopia, India, and Rwanda than reflected by the MTF. According to the MTF’s indicator of affordability, practically no one in Ethiopia or India would be considered unable to afford electricity access. However, if one includes the discounted cost of appliances needed to consume electricity in the indicator, about a third of the population in India and Ethiopia might be categorized as facing issues with affordability. In Rwanda, even without considering the discounted cost of appliances, most electricity consuming households are faced with affordability constraints to using basic electric services at home.

This evolution of measuring energy access is just a first step to more accurately counting the energy poor. This needs to go hand in hand with better data gathering, especially for countries and regions that face the biggest challenges in terms of extending access to modern energy services. Further refinements and applications of the framework can help improve how we identify the most vulnerable and design and target policies to achieve true energy access for all.

This blog post was first published on the PowerForAll Energy policy website. Read the original article here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 13, 2021 | Communication, Egypt, Women in Science

By Shorouk Elkobros, IIASA Science Communications Fellow

Shorouk Elkobros shares her love for science communication and why she thinks it is pivotal for humanity.

Early 2020, I saw viral GIFs about social distancing and flattening the curve. I remember how useful and accessible it felt to have science communicated in such a fun and non-jargon way, especially during a global crisis.

In today’s post-truth world, misinformation campaigns travel fast. Hence, science communication’s role becomes pivotal to humanity. Anne Glover, the president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, once said that “research not communicated is effectively research not done.”

What is science communication?

Science communication is the practice of educating and raising awareness of science-related topics. Science communicators, therefore, aspire to bridge the gap between science and the public and to inform decision makers.

But is it that easy?

You guessed it ̶ it is not. However, it is a challenge one would love to take on. Science communication is a constant game of problem solving.

Meme from the American sitcom television series Parks and Recreation | awwmemes.com

It is never about dumbing down information but rather about making it concise and clear. It requires a decent amount of practice, careful attention to language, and a deep understanding of the audience.

Enticing readers with clickbait information and sensationalized or misleading facts has almost pushed the reputation of science communication under the bus. Examples include the COVID-19 conspiracy theories that emerged amid the pandemic or climate change deniers’ campaigns that share fake scientific news to mislead the public.

Why I love science communication?

I come from a science background and a love for visual storytelling. After earning my master’s degree in climate sciences, I chose to become a science communicator because it brings me joy to make science relatable and fun for the public. For me, science communication is a great way to mainstream climate action.

In 2019, I worked closely with the CLICCS B1 team at the University of Hamburg, Germany, where I investigated how our imaginations of possible and plausible climate futures are socially and culturally constituted and embedded in broader visions of the future and belief systems. One thing I learned was that the mainstream media either tones down the climate crises or spreads alarming and apocalyptic messages. It was an eye-opening experience to investigate how climate change is communicated in the media and to recommend amends. However, I always wanted to practice what I preached. I was lucky to volunteer as an editor on the Climate Matters blog and as a video editor in conferences such as Tropentag 2019. The sense of satisfaction that I felt every time I worked on an article or a video made me realize that I want to pursue a career in science communication.

IIASA Science communication

In 2020 I was looking for opportunities to embark on a science communication learning journey to become a better science writer and a better storyteller. Having the chance to do a Science Communication Fellowship at IIASA was an experience that I hold near and dear to my heart. This program is targeted towards early career science communicators who want to sharpen their science communication skills. It was the perfect opportunity for me to transition from academia to the practical field.

Working closely with researchers to produce content on blogs, videos, and news-in-brief articles in the Options magazine 2020 winter edition gave me an excellent perspective on environmental, economic, technological, and social change all around the globe. Knowing that my work can provide the needed information to policymakers is so rewarding because I know it can make a change in the years to come. Interviewing early career researchers and IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program alumni, and listening to them discussing their work and future aspirations was awe-inspiring. I think my favorite project was producing a video on the biodiversity work done at IIASA because I was able to look beyond the research and highlight the researchers behind it. I figured one way people would relate to the science is if I put a human face to it.

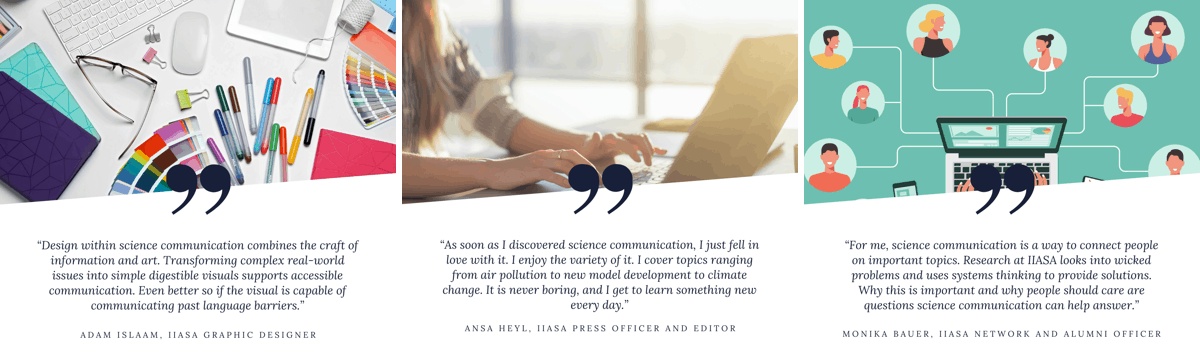

Working as part of the IIASA communications team has been a blast. For this blog, I asked my team members why they love science communication, and here are some of my favorite replies:

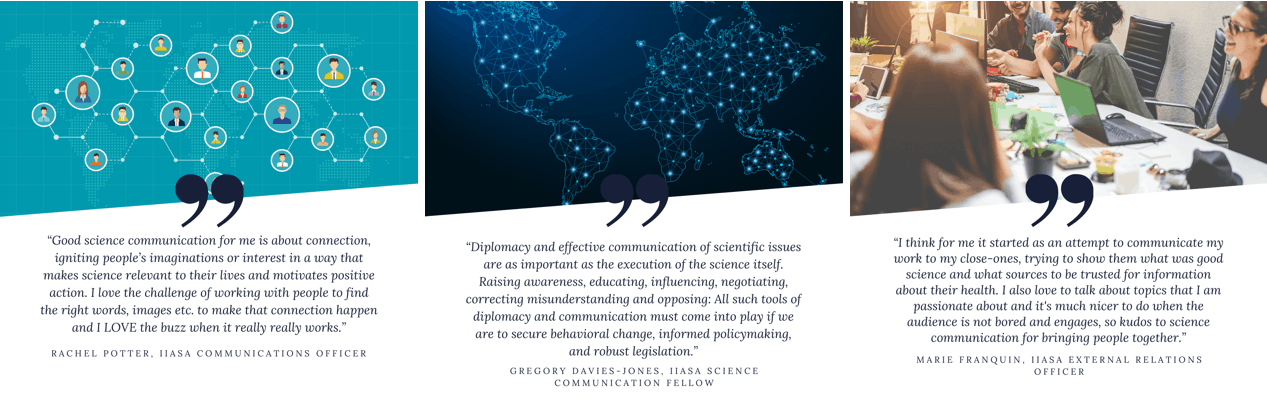

Communicating research addressing issues such as food and water security, biodiversity, or climate change can boost regenerative economies and decentralized renewable energy systems. It then becomes pivotal for humanity to give a voice to young people, grassroots movements, and people of color. Historically, researchers involved in outreach gave science communication its modern shape. Today, I think we live in a golden age of science communication. There are more thought-provoking science stories than ever before. Scientists blogging about science, science communicators using social media to promote recent publications, and storytellers creating science-oriented videos or designs, are all doing magnificent work, and I am lucky to count myself as one of them.

Communicating research addressing issues such as food and water security, biodiversity, or climate change can boost regenerative economies and decentralized renewable energy systems. It then becomes pivotal for humanity to give a voice to young people, grassroots movements, and people of color. Historically, researchers involved in outreach gave science communication its modern shape. Today, I think we live in a golden age of science communication. There are more thought-provoking science stories than ever before. Scientists blogging about science, science communicators using social media to promote recent publications, and storytellers creating science-oriented videos or designs, are all doing magnificent work, and I am lucky to count myself as one of them.

@ Lennart Wittstock | Pexels.com

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 7, 2020 | Biodiversity, Climate Change, Food & Water, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Shorouk Elkobros, 2020 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Being mindful of biodiversity loss and environmental impact can disrupt the beef industry globally, here’s how.

In his new polemical Netflix documentary, A life on our planet, Sir David Attenborough argues that, “We live on a finely tuned life support machine, one that relies on its biodiversity to run smoothly.”

The decline in biodiversity challenges the world’s capacity to produce food for a growing population. That is ironic when global food production itself is a contributing factor to biodiversity loss, especially beef production.

What’s wrong with the beef industry?

Here are a couple of the current challenges facing the beef industry: Cows are major culprits in climate change because they emit methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Beef production is the number one driver of deforestation and habitat loss in tropical forests. Grazing cattle also require a large amount of grass that requires using harsh nitrogen fertilizers. Hence, the beef production industry contributes heavily to biodiversity loss, which has dire consequences for the planet.

©Jonathan Casey | Dreamstime.com

There is no silver bullet to solve the challenges beef production poses to the environment. Research is going above and beyond to find diverse and integrated solutions that can go hand in hand to combat this challenge. Whether through ways to reduce methane emissions, such as creating an anti-burp vaccine for cows, designing lab-grown meat, or shifting diets to plant-based alternatives.

Katie Lee, an alumna of the 2020 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) and PhD student at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, is part of a broader project that focuses on redistributing where we produce beef to minimize its impact on greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity, as well as on the cost of production.

“I am particularly interested in ways to enhance the types of beef production systems. With the challenges of its water use, greenhouse gas emissions, and the large areas of land it requires compared to any other food source, any small changes we propose can have a big impact,” she explains.

For Lee, solutions to global food security are crucial, and looking at the status of production systems is both a need and a must. The world population is expected to reach 9.7 billion people by 2050. So, when thinking about ways to feed 10 Billion people by 2050, it becomes clear that it is not enough to simply look at beef alternatives without enhancing its current demand and supply chains. Lee thinks it is more efficient to pragmatically alter and improve the environmental impact of beef production than to convince people to stop eating beef.

It is understood that reducing beef consumption has health benefits. However, with a growing interest in alternative meat options, the question remains of which markets this appeals to, and how environmentally friendly and energy- and water intensive these alternatives are.

“While demand reduction on meat is important, sometimes it is not feasible in countries that do not have economic security or are still growing in terms of affluence, which leads to an increase in beef consumption. That is why we need to look at the producer side and the consumer side, as well as everything in between to have the biggest impact. I was particularly interested to conduct this research in cooperation with IIASA, mainly because the institute has a good history of looking at the impact of beef, particularly in terms of greenhouse gas emissions,” says Lee.

A win-win all-round solution

Using the IIASA Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM), Lee is assessing the impact on greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity when shifting both the production and demand of beef. Preliminary results from her ongoing study show a reduction in impact on biodiversity and greenhouse gas emissions, as well as a reduction of the producer price when switching away from extensive grazing systems ̶ a win-win situation all-round.

“Few studies explicitly address biodiversity loss compared to investigating ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. I want to show stakeholders that beef production can be more efficient in terms of reducing its impact on greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity. I am hopeful that this study can help beef producers to be mindful of this when making choices. That will be a win for the environment if it goes together with a proactive reduction of meat consumption,” concludes Lee.

Similar to Lee’s study and using a set of large-scale economic models including GLOBIOM, the IIASA AnimalChange research project aims to assess the global scale adaptation and mitigation options of the livestock sector to ensure a sustainable livestock production sector by 2050.

Limiting global warming and protecting biodiversity should be a priority when designing food systems able to feed an increasing population. As a food producer, whether you raise cattle or design cell cultured meat, it is important to be conscious about livestock hoof prints on biodiversity. As a food consumer, it is necessary to be mindful of having a healthy and sustainable diet that does not put the planet in jeopardy. Sustainable beef production might not be the panacea to future biodiversity loss or food scarcity, yet it can offer a significant change.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 11, 2020 | COVID19, Data and Methods, Science and Policy, Women in Science

By Sibel Eker, researcher in the IIASA Energy Program

IIASA researcher Sibel Eker explores the usefulness and reliability of COVID-19 models for informing decision making about the extent of the epidemic and the healthcare problem.

© zack Ng 99 | Dreamstime.com

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when facts were uncertain, decisions were urgent, and stakes were very high, both the public and policymakers turned not to oracles, but to mathematical modelers to ask how many people could be infected and how the pandemic would evolve. The response was a plethora of hypothetical models shared on online platforms and numerous better calibrated scientific models published in online repositories. A few such models were announced to support governments’ decision-making processes in countries like Austria, the UK, and the US.

With this announcement, a heated debate began about the accuracy of model projections and their reliability. In the UK, for instance, the model developed by the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis at Imperial College London projected around 500,000 and 20,000 deaths without and with strict measures, respectively. These different policy scenarios were misinterpreted by the media as a drastic variation in the model assumptions, and hence a lack of reliability. In the US, projections of the model developed by the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) changed as new data were fed into the model, sparking further debate about the accuracy thereof.

This discussion about the accuracy and reliability of COVID-19 models led me to rethink model validity and validation. In a previous study, my colleagues and I showed that, based on a vast scientific literature on model validation and practitioners’ views, validity often equates with how good a model represents the reality, which is often measured by how accurately the model replicates the observed data. However, representativeness does not always imply the usefulness of a model. A commentary following that study emphasized the tradeoff between representativeness and the propagation error caused by it, thereby cautioning against an exaggerated focus on extending model boundaries and creating a modeling hubris.

Following these previous studies, in my latest commentary in Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, I briefly reviewed the COVID-19 models used in public policymaking in Austria, the UK, and the US in terms of how they capture the complexity of reality, how they report their validation, and how they communicate their assumptions and uncertainties. I concluded that the three models are undeniably useful for informing the public and policy debate about the extent of the epidemic and the healthcare problem. They serve the purpose of synthesizing the best available knowledge and data, and they provide a testbed for altering our assumptions and creating a variety of “what-if” scenarios. However, they cannot be seen as accurate prediction tools, not only because no model is able to do this, but also because these models lacked thorough formal validation according to their reports in late March. While it may be true that media misinterpretation triggered the debate about accuracy, there are expressions of overconfidence in the reporting of these models, even though the communication of uncertainties and assumptions are not fully clear.

© Jaka Vukotič | Dreamstime.com

The uncertainty and urgency associated with pandemic decision-making is familiar to many policymaking situations from climate change mitigation to sustainable resource management. Therefore, the lessons learned from the use of COVID models can resonate in other disciplines. Post-crisis research can analyze the usefulness of these models in the discourse and decision making so that we can better prepare for the next outbreak and we can better utilize policy models in any situation. Until then, we should take the prediction claims of any model with caution, focus on the scenario analysis capability of models, and remind ourselves one more time that a model is a representation of reality, not the reality itself, like René Magritte notes that his perfectly curved and brightly polished pipe is not a pipe.

References

Eker S (2020). Validity and usefulness of COVID-19 models. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7 (1) [pure.iiasa.ac.at/16614]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jun 3, 2020 | COVID19, Health, Science and Policy, Women in Science

By Nicole Arbour, external relations manager in the IIASA Communications and External Relations department

As Canadian expats in Austria, one of the things that has particularly struck my family and I is the orderliness with which the country is dealing with the pandemic. As quarantine policies were put into place, we saw panic toilet paper hoarding in other countries, but here in Austria people were (amazingly) compliant and seemed to obey instructions and timelines provided by the authorities. We never worried about our basic needs. Grocery stores were always well stocked, public transit was always there and on time – and masks were readily available when required as physical barrier to protect others.

© Luca Santilli | Dreamstime.com

Expert opinions, governments, and publics are making it clear that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to this pandemic. What works in Austria might not be what worked for South Korea; and likely not the same as what works in other parts of Europe. Consider the Canadian landscape. There is huge variation in sociopolitical and cultural dynamics between and within provinces and territories. What works for some parts of Canada (virtual home schooling, grocery shopping) is impossible for others (Canada’s North). Cultural norms (multigenerational living, child/elder care) vary across the vast landscape. The “At Home on the Land” initiative – aimed at the particular needs of Indigenous communities is an example of a culturally-grounded way to address the pandemic. Finding solutions isn’t always as intuitive as we might like.

Humans tend to look for the easiest way out – we want simple solutions to complex problems. We don’t seem to want to think about the problems, we want them magically disappear. And thinking “outside of the box” isn’t always appreciated. Hand washing, clean water and the advent of antibiotics have made enormous leaps in our ability to tackle public health outbreaks – significant results. Where the bubonic plague is estimated to have killed 30%-60% of Europe’s population in the Middle Ages, modern outbreaks are now quickly identified and contained (were you even aware of the 2017 outbreak in Madagascar?). Understanding transmission routes has significantly impacted public health outcomes. The identification of tainted water as a vector for cholera transmission by John Snow led to the advent of modern epidemiology. But, as we find solutions to larger challenges, those that remain are more complex with increasing numbers of variables making solutions harder to come by.

There is some global agreement: lots of testing, quick results/containment, use of masks/physical barriers for community protection, social distancing, data collection. However, certain measures work better in some jurisdictions than others. What policies and practices are working and why are they working in these contexts? What is applicable in different contexts?

Our current global situation, has reminded me of a presentation I saw on the 2014 Ebola outbreak (Professor Melissa Leach, IDS), and how important it is to remember the human factor in crises. She discussed how the key elements that made the Ebola pandemic so persistent – despite the best efforts of global public health engagement – was a/the failure to understand how historic context, trust, cultural dynamics played into the spread of the virus. Those providing interventions did not appreciate how historic context (i.e. post-colonialism, slavery, medical testing scandals) and mistrust in the intentions of Western interventions factored into the willingness of the local population to accept the solutions provided. Awareness of social structures, influencers and leaders, and co-creation were also important to developing solutions that would be adopted by affected communities.

Evidence is more than the numbers of tests, infections and deaths. It is understanding the social context of communities, society writ large, and how they interact within and between. It’s about understanding historical context and how it feeds into local culture, social interactions and trust relationships. It’s about community dynamics, power struggles and the struggle for some to meet basic survival needs. It’s about timing of decision-making, political landscapes and different ways of leading. As with many of our global challenges, it’s a complex and multifaceted systems problem – in which the human factor is a huge driver.

As we strive for solutions to this global crisis – bring on innovation, research and science funding. We will need these – but please, also bring along those who study the complexity that is humanity: epidemiologists, anthropologists, economists, ethicists, political scientists, sociologists, futurists, etc. In an era where evidence is being questioned, fake news is rampant and anti-science sentiments are strong, it is crucial that we remember that one piece to engaging with this and the world’s other wicked problems is our relationships with our communities – the ones we are trying to protect. Public trust, built on understanding of the importance of human dynamics is key to broad acceptance and uptake. Solutions need to be palatable to society, or they won’t be adopted.

As we focus on the virus, let’s not forget the humans.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. Link to original post: https://sciencepolicy.ca/news/save-covid19-lets-not-forget-humans

May 14, 2020 | Alumni, Postdoc, Sustainable Development, Women in Science

By Raquel Guimaraes, postdoc in the IIASA World Population Program, and Debbora Leip, an alumnus of the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program

IIASA researcher Raquel Guimaraes and former research assistant Debbora Leip encourage the support of the Cercedilla Manifesto, arguing that it is high time for the scientific community to take responsibility and set an example by making research meetings more sustainable.

© La Fabrika Pixel S.l. | Dreamstime.com

The research community widely agrees that strong action is needed to counteract the climate crisis that is currently taking place. Nevertheless, scientists regularly meet at conferences that are often far from sustainable. Problems range from participants flying to attend events, to unnecessary gadgets and gifts handed out at the meetings, and unsustainable catering at conference dinners. In light of the current public debate on environmental and social sustainability, we call on scientists to take a leading role in changing their work practices towards more sustainable habits, starting with research meetings.

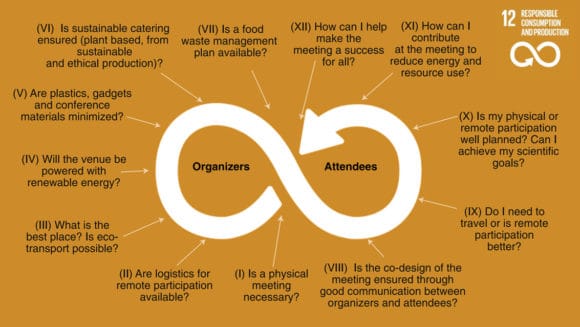

In April 2020, Alberto Sanz-Cobena and several colleagues published an article titled Research meetings must be more sustainable in Nature Foods. They presented the Cercedilla Manifesto with 12 sustainability decisions as guidelines for organizers and attendees of research meetings (see Figure 1). The starting point of the manifesto is to question whether a physical meeting is indeed necessary. If organizers decide that it is, there is still the question of whether each single attendee really needs to physically join the conference. Often, remote participation can be equally efficient if a technical solution is provided by the organizers. Furthermore, if a decision to conduct a physical meeting is taken, organizers have to consider what food will be served.

The authors state that excessive amounts of food and food waste are very common at meetings, which makes a change of mindset towards better food management very important, not only for climate change, but for many other environmental threats. In our opinion, this point has so far been neglected in public debate.

Given the urgency for climate change action and the need for individuals to play an active role – with research scientists taking the lead – we assert that it is urgent to start changing our habits and setting an example regarding environmental and social sustainability in research meetings. Indeed, many of us take it for granted that to meet and discuss our work, we must travel. Most attendees do not even question that unnecessary gadgets and gifts are distributed or that opulent dinners are provided.

We hope that the Cercedilla Manifesto will raise awareness about the fact that good scientific output often does not require a physical meeting by providing a conceptual framework for change in this regard. If we support the manifesto, we stand a chance to lower the barrier to dare deviating from currently applied practices. The 12-sustainability decisions were designed by specialists to serve as a reference for anybody who wishes to organize/attend a sustainable meeting.

In the current situation brought about by the global COVID-19 crisis, almost everybody has experienced that remote conferences are not only possible, but also efficient – sometimes even more so than a physical meeting would have been. First, it saves time in terms of travel. Second, it may be more inclusive by allowing people to attend, who would not have had the opportunity to join otherwise, be it for financial, family, or other reasons. In addition, remote meetings provide additional features, like a chat function that could add another discussion layer.

Of course, remote meetings also have their limitations: informal in-person meetings during coffee breaks, for example, can enhance networking and free discussions, and sometimes contribute significantly to a meeting’s outcome. Virtual meetings also face several other challenges, such as participation by attendees from different time zones, or poor internet connections. These issues could however easily be addressed by spreading the meeting over more days, in such a way that the need for attendance outside of acceptable time slots is minimized, and by investing saved traveling costs into better equipment.

Let us learn from this experience and not go ‘back to normal’ after the COVID-19 crisis. We should take this as an opportunity to speed up change and tackle the other global crisis of climate change!

You can find the petition at openpetition.eu/!cercedillamanifesto. We encourage you to share and support this initiative.

References:

Sanz-Cobena A, Alessandrini R, Bodirsky BL, Springmann M, Aguilera E, Amon B, Bartolini F, Geupel M, et al. (2020). Research meetings must be more sustainable. Nature Food 1, 187–189. DOI: 10.1038/s43016-020-0065-2

Frisch B, & Greene C (2020). What it takes to run a great virtual meeting. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/03/what-it-takes-to-run-a-great-virtual-meeting?ab=hero-subleft-3

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Communicating research addressing issues such as food and water security, biodiversity, or climate change can boost regenerative economies and decentralized renewable energy systems. It then becomes pivotal for humanity to give a voice to young people, grassroots movements, and people of color. Historically, researchers involved in outreach gave science communication its modern shape. Today, I think we live in a golden age of science communication. There are more thought-provoking science stories than ever before. Scientists blogging about science, science communicators using social media to promote recent publications, and storytellers creating science-oriented videos or designs, are all doing magnificent work, and I am lucky to count myself as one of them.

Communicating research addressing issues such as food and water security, biodiversity, or climate change can boost regenerative economies and decentralized renewable energy systems. It then becomes pivotal for humanity to give a voice to young people, grassroots movements, and people of color. Historically, researchers involved in outreach gave science communication its modern shape. Today, I think we live in a golden age of science communication. There are more thought-provoking science stories than ever before. Scientists blogging about science, science communicators using social media to promote recent publications, and storytellers creating science-oriented videos or designs, are all doing magnificent work, and I am lucky to count myself as one of them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.