Jan 13, 2022 | Austria, Climate Change, COVID19, Energy & Climate, Sustainable Development

By Thomas Schinko, IIASA Equity and Justice Research Group Leader in the Population and Just Societies Program

IIASA researcher Thomas Schinko discusses the visionless outcomes of the recent UN Climate Conference (COP26) in Glasgow and an Austrian project he is involved in, which aims to co-create courageous and positive visions for a low-carbon and climate resilient future.

© Kengmerry | Dreamstime.com

In December 2015, the international community agreed to limit global average temperature increase to “well below 2°C” above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to hold them to 1.5°C under a landmark agreement known as the Paris Climate Accord. At COP26, which many considered the real follow-up to Paris, nations were asked to present updated plans and procedures to deliver in Glasgow what Paris promised.

While this ambitious goal was not achieved with the Glasgow Climate Pact and many delegates speaking in the closing plenary expressed disappointment, COP26 President Alok Sharma said that at least it “charts a course for the world to deliver on the promises made in Paris”, and parties “have kept 1.5°C alive”. However, parties substantially differ in their views around whether COP26 actually kept the 1.5°C target within reach.

In the time between Paris and Glasgow, we have seen the climate crisis unfolding in almost all parts of the world, with record heatwaves, storms, heavy rains, floods, droughts, wildfires, rising sea levels, and melting glaciers, to name but a few. At the same time, and notwithstanding many nations’ existing mitigation pledges, global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are still on the rise, and despite the small temporary dent to the upward sloping curve induced by COVID-19 pandemic related impacts on the world economy, there is no turning point in sight. While more and more nations are setting net-zero targets towards the middle of the century – most recently India announced reaching net-zero at COP 26, although only by 2070 – there is still a lack of intermediate steps, concrete measures, and financing strategies around how to achieve those targets.

What we need to achieve climate neutrality by mid-century and thereby stand a decent chance of preventing the worst effects of the climate crisis, is an immediate and drastic U-turn in the global GHG emission trajectory, rather than slowly reaching a turning point. The cuts required per year to meet the projected emissions levels for 2°C and 1.5°C are now 2.7% and 7.6% respectively, from 2020 and per year on average. This in turn requires sudden and drastic climate action at different policy and governance levels, rather than some incremental policy and behavioral changes.

However, many policy- and decision makers, as well as other societal stakeholders, consider such radical change impossible. I am positive we have all heard many excuses for slow progress in climate action, including that people won’t tolerate any climate policy measures that would require a palpable change in their lifestyles, habits, and routines; or that there is no money after carrying our economies through the economic crisis induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Other favorites are that “there is no alternative to our growth-based economic model”; or “our industries cannot just change their business models from one day to another”.

Overall, such excuses are blatant manifestations of a more general observation: At the heart of political failure there is often a lack of imagination or vision. One might argue that the policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have shown that governments are able to actually govern, and people were ready to profoundly change their behaviors. However, the overarching policy narrative was suggesting that these changes are all temporary and that once the pandemic is under control, we will move back to the pre-crisis state. In the context of the climate crisis and other closely related grand global challenges such as the biodiversity crisis, a “back to the future” narrative is at least useless and in the worst case even counterproductive.

To operationalize the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal and the follow-up Glasgow Climate Pact, we need courageous forward-looking visions that go beyond technology scenarios by describing what a climate neutral and resilient society could look like in all its complex facets. Last minute interventions at COP26 to tone down the Pact’s wording on fossil fuels to “phasing down” unabated coal power and “phasing out” inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, have proven once more that international climate policymaking is a tough diplomatic struggle, but also that it still suffers from a chronic lack of imagination at all levels.

Also at the individual level, recent research has found that while citizens are alarmed by the climate crisis, few are willing to act proportionately as they lack a clear vision of what a low-carbon transformation actually means. If we are not able to develop courageous visions of low-carbon and climate resilient futures that generate broad societal buy-in, we will not be able to identify and implement radical and transformational climate actions that will catapult us onto the low-carbon trajectories that have been laid out by scientists for achieving the 1.5°C goal. Hence, these visions need to be co-created with all relevant societal stakeholders that have a legitimate claim in the low-carbon transformation of our societies.

In developing such joint visions, it is of the utmost importance to first understand and eventually negotiate between different imaginations of a livable future and perceptions of what constitutes fair outcomes of, and just process for this fundamental transformation our societies will have to undergo.

In Austria, as in many other countries, national and sub-national governments are announcing net-zero targets and starting to think about the strategies and measures needed to achieve those. With a transdisciplinary group of researchers, practitioners, and policy- and decision makers, we are developing a participatory process for Styria, one of Austria’s nine states, that aims to co-create courageous and positive visions for a low-carbon and climate resilient future with a representative group of about 50 people. The central building block of this process is a co-creation workshop called “climate modernity ̶ the 24-hour challenge”. This weekend workshop will not take up more than 24 hours in total of participants’ time and it not only aims to imagine visions, but also to back-cast from these visions what is required to achieve them.

With this process, we set out to support the development of a new, politically as well as societally feasible, climate, and energy strategy for Styria. The Klimaneuzeit website, which includes an online application form that allows for eventually inviting a representative group of participants, has just been launched. Stay tuned to find out more about our lessons learned in co-developing this visioning process and implementing this prototype in Austria.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 7, 2021 | Climate Change, Environment, Food & Water, Sustainable Development

By Stefan Frank, researcher in the Integrated Biosphere Futures Research Group of the IIASA Biodiversity and Natural Resources Program

Stefan Frank discusses a recent study that looked into the impacts of ambitious EU agricultural mitigation policies on the livelihoods of farmers.

© Milkos | Dreamstime.com

Balancing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and removals in the land-use sector by 2035 is one of the key milestones presented in the European Green Deal, but achieving climate neutrality will require further emission cuts in the agricultural sector. However, when it comes to setting ambitious mitigation targets for the sector, (national) policymakers are often reluctant to make strong commitments.

One reason could be the close interactions of agriculture with other policy objectives related to climate change mitigation, such as sustained food production, nutrition security, or biodiversity. Even though agricultural policies are frequently implemented using subsidies, such as in the European Union Common Agriculture Policy, policymakers strive to find a balance that ensures progress on these goals while at the same time not overburdening farmers.

Another fear is that ambitious mitigation efforts could cause economic losses for EU farmers whose income already relies heavily on subsidies. Reducing emissions could for instance lead to increased production costs and a consequent deterioration in the cost-competitiveness of EU farmers when comparing domestic production with imports. For example, the adoption of mitigation practices such as precision farming or anaerobic digesters increase costs, and the reduction in fertilizer application as suggested in the Farm to Fork Strategy may also directly impact crop yields and subsequently revenues.

In our study recently published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, we investigated the impacts of an ambitious EU agricultural mitigation policy on agricultural markets, farmers, and GHG emissions applying an ensemble of agricultural sector models. We investigated two alternative scenarios.

The first scenario represents a situation where only the EU adopts stringent mitigation efforts for agriculture compatible with the 1.5°C target at global scale, while the second imagines a world where other world regions also take action.

Figure from Frank et al. (2021): Average impact across models of different levels of ROW mitigation ambition on EU agricultural production, prices and production value corrected for carbon tax payments in 2050. RUM—ruminant beef, DRY—milk, NRM—non-ruminant meatand eggs, CGR—coarse grains, WHT—wheat, and OSD—oilseeds.

We found that EU beef producers are strongly affected if only the EU pursues stringent agricultural emission reduction efforts. For example, cutting EU agricultural non-CO2 emissions by close to 40% (155 MtCO2eq/yr) in 2050 could result in a 22% decline in EU beef production. Despite emission leakage effects through reallocation of production outside the EU, a unilateral mitigation policy delivers climate benefits and yields net emission savings at global scale of around 90 MtCO2eq/yr.

Once regions outside Europe start to pursue mitigation efforts that are compatible with those in the EU, economic impacts on EU farmers are distributed more equally across world regions as farmers outside the EU are included in the mitigation policy and start contributing. Since EU farmers rank among the most GHG efficient producers at global scale, with increasing mitigation efforts in other world regions, EU farmers don’t lose their competitiveness, even if the EU pursues 1.5°C compatible efforts.

Unlike in the unilateral EU policy, EU farmers could even start to benefit from a globally coordinated mitigation policy beyond a certain point. For example, if regions outside the EU were to pursue at least half the effort implemented in the EU and were required to reach the 1.5°C target globally, the economic value of production of EU beef and non-ruminant producers could exceed baseline scenario projections without any mitigation efforts in agriculture.

Similar effects are observed for other world regions with GHG-efficient agricultural production systems, while GHG intensive producers are projected to lose market shares. Given differences in GHG mitigation efficiencies and economic prospects across world regions, accompanying distributional policies such as climate finance policies could help to alleviate the risk of mitigation induced food security or poverty issues. Our study highlights these economic challenges and opportunities for farmers related to the required transition of the global food system to achieve the 1.5°C target.

Further info:

Frank, S., Havlik, P, Tabeau, A., Witzke, P., Boere, E., Bogonos, M., Deppermann, A., van Dijk, M., et al. (2021). How much multilateralism do we need? Effectiveness of unilateral agricultural mitigation efforts in the global context. Environmental Research Letters 16 (10) e104038. DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac2967 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17492]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 26, 2021 | Demography, Environment, Finland, IIASA Network, Poverty & Equity

By Venla Niva, DSc researcher with the Water and Development Research Group, School of Engineering, Aalto University, Finland

Venla Niva shares insights from a recent article exploring the interplay of environmental and social factors behind human migration. The project was carried out in collaboration with Raya Muttarak from the IIASA Population and Just Societies Program.

© Irina Nazarova | Dreamstime.com

Environmental migration has gained increasing attention in the past years, with recent climate reports and policy documents highlighting an increase in environmental refugees and migrants as one of the potential effects of the warming globe. Policymaking is dominated by a narrative that portrays environmental migration as a security threat to the “Global North”. Meanwhile, researchers around the world have put enormous efforts into understanding environmental migration and what is driving it. Yet, the causes and effects of environmental migration remain under debate.

In our latest paper, we extend the understanding of environmental migration by looking into how environmental and societal factors interacted in places of excess out- or in-migration between 1990 and 2000. We found that understanding these interactions is key for understanding migration drivers. Ultimately, migration is based on human decision-making, and in our view “simply cannot and should not be studied without the inclusion of the societal dimension: human capacity and agency.” Our findings were both expected and, to a certain degree, surprising.

Our results show that the majority of global migration takes place in areas with rather similar profiles. It is known that migration mostly occurs over short distances, and that internal migration – in other words, people moving around in their own country – outplays international migration – people moving between countries – by significant numbers globally. This, however, shows that the characteristics of these areas are alike too. High environmental stress coupled with low-to-moderate human capacity characterized these areas at both ends of migration. Such characteristics portray a combination of variables with a high degree of drought and water risks, natural hazards, and food insecurity, but low levels of income, education, health, and governance.

We found that income was the best variable to explain the variation of net-negative and net-positive migration in around half of the countries, globally, confirming that income is a good predictor of migration. This is interesting in two ways. According to traditional migration theories, income disparity between regions is seen as the primary driver for migration. Yet, income only dominated the other variables in half of the countries we examined. Education and health were especially important in areas with more out-migration than in-migration. Drought and water risks were important explaining factors in many countries, but were outranked by societal factors such as income, health, education, and governance in the majority of countries.

In light of our research, we would like to point out that it is unlikely that environmental factors alone would be responsible for migration. Instead, the role of human agency is vital. Investments in building human capacity have two-fold benefits: First, higher human capacity facilitates not only local adaptation to changes in the environment, but also adaptation at the destination in case of migrating. Second, protecting ecosystems and the environment helps to mitigate and adapt to climate and environmental change in areas with high environmental stress, which is again crucial for maintaining livelihoods and a good life at both ends of migration.

Environmental migration is often portrayed by the media as a catastrophic phenomenon. Our study confirms that migration drivers are a result of the interactions between socioeconomic and environmental factors and that human capacity plays a central role in both enabling the migration process and adaptation at the place of destination.

Further info:

Niva, V., Kallio, M., Muttarak, R., Taka, M., Varis, O., & Kummu, M. (2021). Global migration is driven by the complex interplay between environmental and social factors. Environmental Research Letters DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac2e86. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17507]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 11, 2021 | Brazil, Economics, Environment

By Fanni Daniella Szakal, 2021 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

In an attempt to foster economic development for Brazil, the government is planning to open up indigenous and protected areas for mining. But will this truly lead to economic development for the country? 2021 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant, Sebastian Luckeneder is using spatial modeling to find out.

© Prabhash Dutta | Dreamstime.com

As the largest rainforest on the planet, the Amazon harbors the highest biodiversity of all ecosystems and is home to many indigenous tribes. It is also literally sitting on a goldmine of natural resources. There are plans in the works to open up protected and indigenous areas of the rainforest to mining activities, which is expected to bring more wealth and development for the country, but at the same time, it will also pose a threat to the environment and indigenous communities.

At first glance, the issue looks like the classic trade-off between economic growth versus environmental and social disruption. In reality however, mining affects social, environmental, and economic spheres both directly and indirectly, creating a complex network of interactions that potentially defy the current dogma.

Mining relies heavily on machines while creating relatively few jobs in comparison to the investment of capital it requires. In addition, mining companies are often large international corporations, which means that most of the profits gained from mining operations in a particular country end up outside that country’s borders.

“One could say that just the very few benefit from extractive activities, whereas many have to pay the cost,” says Sebastian Luckeneder, a 2021 YSSP participant at IIASA, when referring to the environmental destruction, disruption of livelihoods, and displacement of indigenous communities that mining would bring about.

As a second-year PhD candidate at the Institute for Ecological Economics of Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU), Luckeneder is studying the environmental and socioeconomic impacts of mining activities. At IIASA, he used spatial modeling to understand how mining and land use affect regional economic growth in Brazil in the hopes of finding the best economic solution for the country.

Using GDP growth as a proxy for economic development, he looked at the impacts of mining and other types of land use between 2000 and 2020. The model incorporates data on mining, agriculture, and land-use change, as well as other socioeconomic factors, such as employment and infrastructure for about 5,500 municipalities in Brazil.

The study is as complex as it sounds: Luckeneder’s main challenge is to set up a theoretical framework that depicts how the environmental and socioeconomic factors influence each other. Once his comprehensive model is complete, he hopes to get a clear picture of how mining affects the Brazilian economy.

He suspects that while mining activities would bring some economic gains, these might not be sustainable, as the environmental and social upheaval that follow the opening of a mine could negatively impact development in the long-run.

While economic development is important, in the current climate crisis, decisions to enable activities that lead to deforestation cannot be taken lightly. Luckeneder hopes that his results will be used to inform the political debate in Brazil and support policy decisions by the way of science.

Nov 4, 2021 | Climate Change, Data and Methods, Risk and resilience

By Asjad Naqvi and Irene Monasterolo from the IIASA Advancing Systems Analysis Program

Asjad Naqvi and Irene Monasterolo discuss a framework they developed to assess how natural disasters cascade across socioeconomic systems.

© Bang Oland | Dreamstime.com

The 2021 Nobel Prize for Physics, was awarded to the topic of “complex systems”, highlighting the need for a better understanding of non-linear interactions that take place within natural and socioeconomic systems. In our paper titled “Assessing the cascading impacts of natural disasters in a multi-layer behavioral network framework”, recently published in Nature Scientific Reports, we highlight one such application of complex systems.

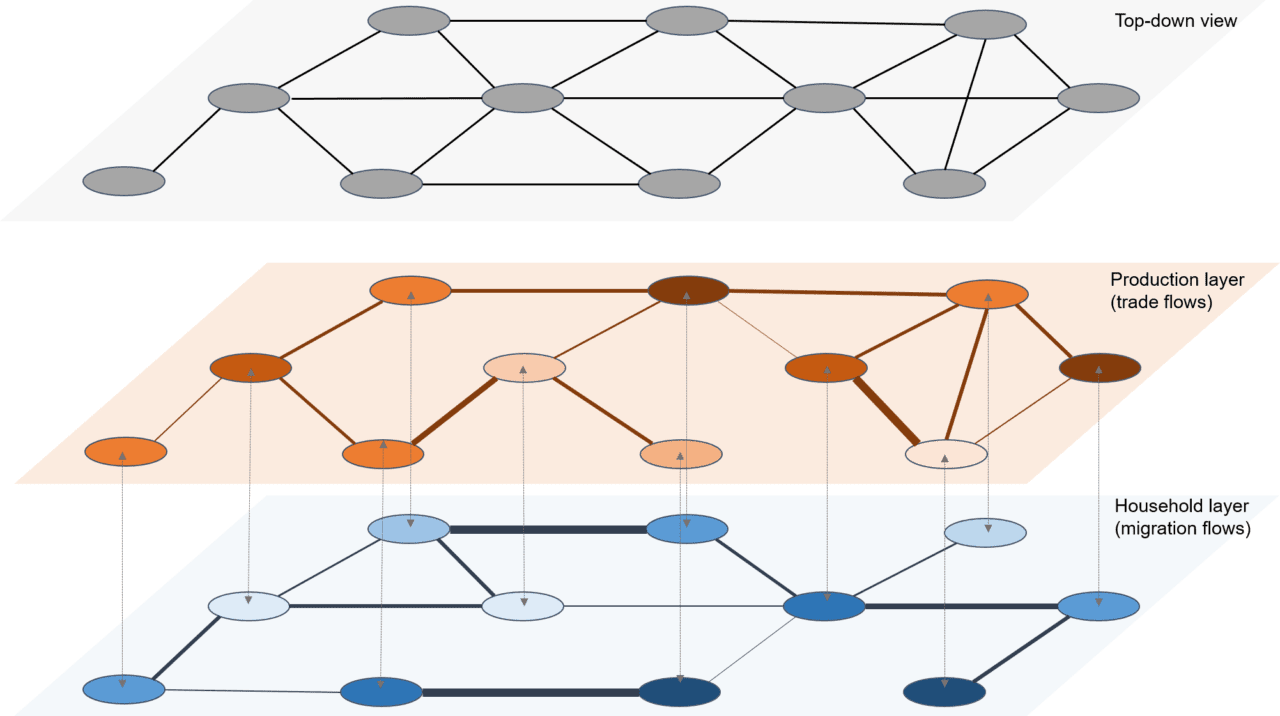

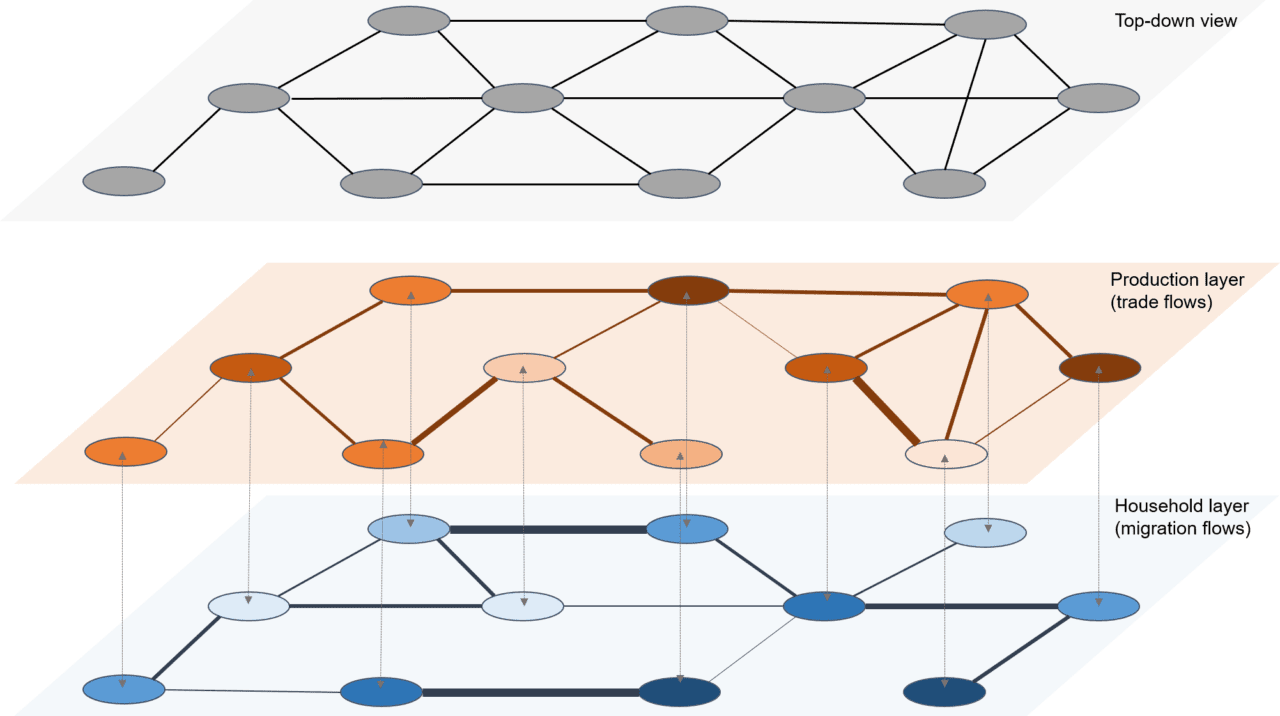

In this paper, we develop a framework for assessing how natural disasters, for example, earthquakes and floods, cascade across socioeconomic systems. We propose that in order to understand post-shock outcomes, an economic structure can be broken down into multiple network layers. Multi-layer networks are a relatively new methodology, mostly stemming from applications in finance after the 2008 financial crisis, which starts with the premise that nodes, or locations in our case, interact with other nodes through various network layers. For example, in our study, we highlight the role of a supply-side production layer, where the flows are trade networks, and a demand-side household layer, which provides labor, and the flows are migration flows.

Figure 1: A multi-layer network structure

In this two-layer structure, the nodes interact, not only within, but across layers as well, forming a co-evolving demand and supply structure that feeds back across each other. The interactions are derived from economic literature, which also allow us to integrate behavioral responses to distress scenarios. This, for example, includes household coping mechanisms for consumption smoothing, and firms’ response to market signals by reshuffling supply chains. The price signals drive flows, which allows the whole system to stabilize.

We applied the framework to an agriculture-dependent economy, typically found in low-income disaster-prone regions. We simulated various flood-like shock scenarios that reduce food output in one part of the network. We then tracked how this shock spreads to the rest of the network over space and time.

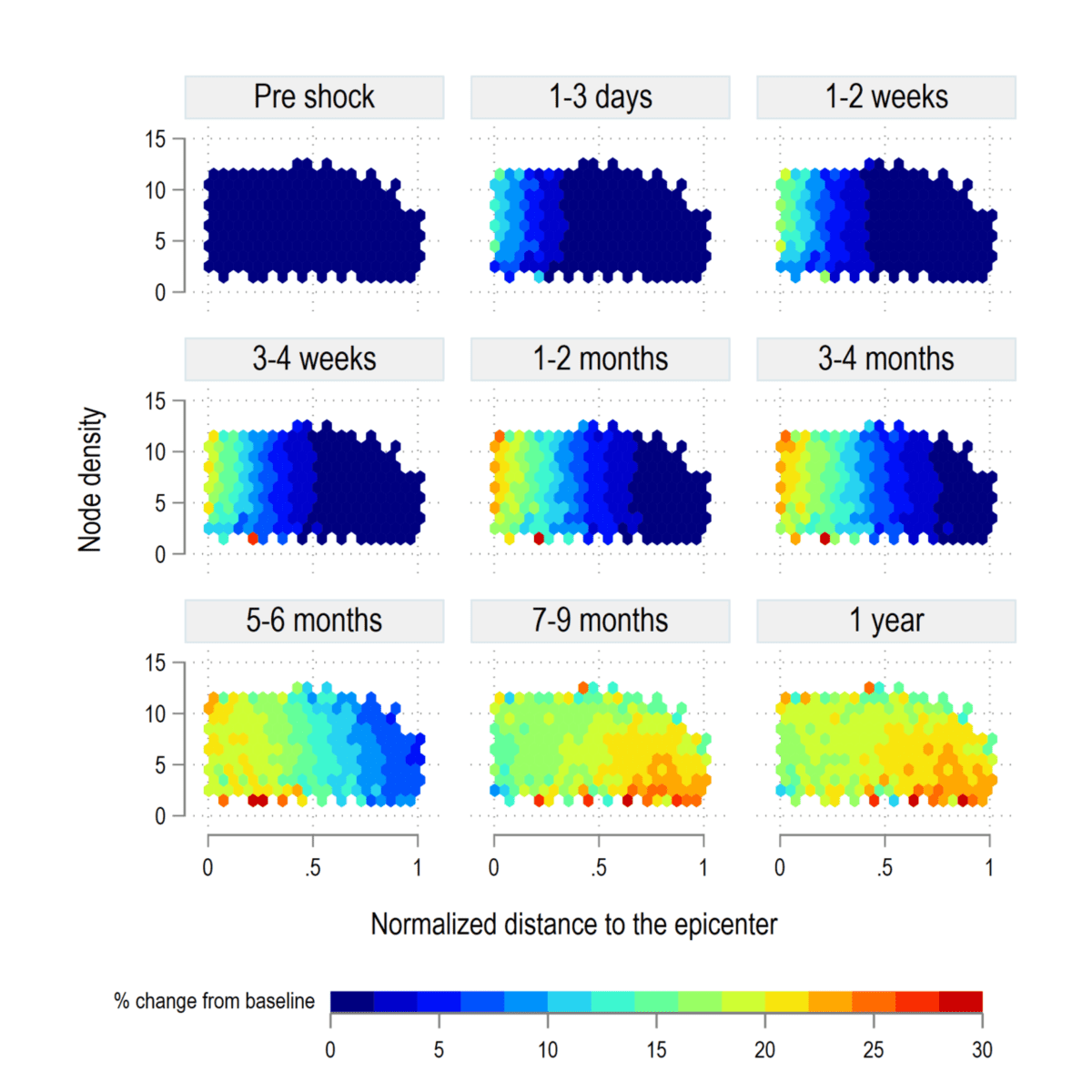

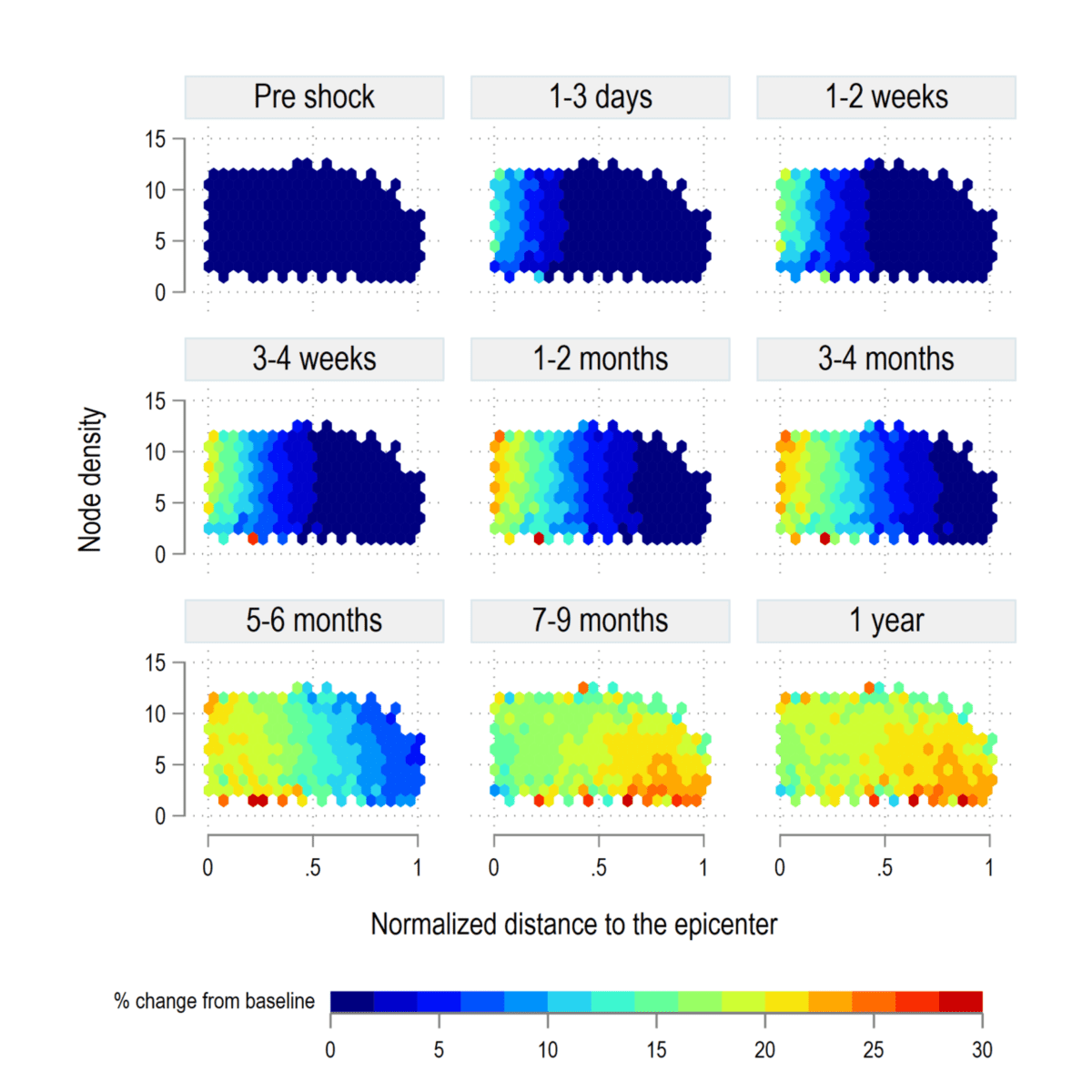

Figure 2: Evolution of vulnerability over time

Our results show that the transition phase is cyclical and depends on the network size, distance from the epi-center of the shock, and node density. Within this cyclical adjustment new vulnerabilities in terms of “food insecurity” can be created. Then, we introduce a new measure, the Vulnerability Rank, or VRank, to synthesize multi-layer risks into a single index.

Our framework can help inform and design policies, aimed at building resilience to disasters by accounting for direct and indirect cascading impacts. This is especially crucial for regions where the fiscal space is limited and timing of response is critical.

Reference:

Naqvi, A. & Monasterolo, I. (2021). Assessing the cascading impacts of natural disasters in a multi-layer behavioral network framework. Scientific Reports 11 e20146. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17496]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.