Jul 8, 2021 | Biodiversity, Food & Water, Science and Policy, Young Scientists

By Neema Tavakolian, 2021 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant Scott Spillias explores how the adoption of offshore seaweed farming could affect land use.

Seaweed farming in the clear coastal waters of Zanzibar island © Ecophoto | Dreamstime.com

Since the start of the industrial revolution, the Earth’s population has grown exponentially, and it is still growing every year. In addition to heavy population growth, human advances in medicine, science, and technology have allowed people to live longer lives as well. As more countries industrialize, the demand for land extensive commodities like meat and dairy have also increased. Deforestation has risen worldwide making way for cattle and other livestock grazing, and more of the food we grow is being dedicated towards livestock rather than human consumption.

With problems like unsustainable land use, climate change, and suburban sprawls in places like the United States and Australia decreasing available arable lands, this poses the question: is there any way we can feed a growing population without further damaging ecosystems and contributing to climate change? In addition to achieving this goal, we simultaneously want to promote equitable and just societies. 2021 YSSP participant Scott Spillias believes he might have a solution: seaweed.

Spillias has a background in marine biology and sailing. After years of sailing the world, he could see the alarming state of our oceans. Wanting to be part of the solution, he moved to Australia to study oceanic food systems, environmental economics, and environmental decision making at the University of Queensland.

Scott Spillias © Scott Spillias

“We live on an ocean planet, yet almost all of the food we grow comes from land. When it comes to the sea, we are essentially just unsustainably hunting and gathering from our oceans. I want to know what it would look like if instead, we tried to farm them,” Spillias explains.

Spillias says that seaweed as an agricultural product is already useful with its range of uses including food, livestock feed, fuel, fertilizer, and multiple products in the form of hydrocolloids. Hydrocolloids, more commonly known as “gums”, are extracted from plants like seaweeds and algae; they are used as setting and thickening agents in a variety of products including foods and pharmaceuticals, often increasing shelf life and quality.

A University of California, Davis study found that incorporating seaweed in cattle feed could reduce methane emissions from beef cattle by as much as 82%. Moreover, seaweed’s broad range of uses can hypothetically decrease land usage in favor of sea usage. Seaweeds also serve many ecological roles such as filtering ocean waters, serving as nurseries for small fish and crustaceans, and protecting sea floors.

There are two types of seaweed farming in use today. In parts of China, South Korea, and Japan there is floating offshore seaweed production, where the seaweed is grown and harvested while floating in deep waters. Another form of seaweed farming seen in Indonesia, Tanzania, and the Philippines involves a different approach, where the seaweed is grown and farmed closer to the coast in shallower waters, or the intertidal zone. Both provide ecosystem services, jobs, and food for local populations.

As part of his YSSP project this summer, Spillias hopes to use the IIASA Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM) to determine land-use changes brought about by large-scale seaweed production.

“We are going to assume that the seaweeds we are growing will be for food, feed, and fuel. We are also taking certain constraints into consideration, such as the inability to place seaweed farms in high traffic shipping areas or marine protected zones. Getting rough estimates of seaweed production can then give us an idea of land commodities we can replace, for instance, corn used for biofuel,” he says.

Spillias hopes that this research can provide results that can influence policy.

“Locally, seaweed farming will either be beneficial or destructive – it depends on where you put it and how you do it. Zooming out and understanding how these tradeoffs relate to terrestrial production will give policymakers a clearer idea of whether to promote or restrict the practice.”

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 5, 2021 | Climate Change, Poverty & Equity, Risk and resilience

By Julian Joseph, research assistant in the Water Security Research Group

Julian Joseph explains the concept of the triple dividend of disaster risk reduction investments based on the application of a novel economic model applied to a case study undertaken in Tanzania and Zambia.

What are the benefits of Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) investments such as dams and the introduction of drought-resistant crops in agriculture for an economy? They are threefold and called the “triple dividend” of DRR investments. The first dividend comprises the direct effects of DRR investments, which limit damage to houses, infrastructure, and other physical assets and prevent death and injury. The second dividend unlocks the economic potential of an economy because risk reduction drives people and businesses to invest more, as they expect less of what they invest in to be destroyed by disasters, while the third dividend is comprised of development co-benefits through other uses the investments provide.

© Gerrit Rautenbach | Dreamstime.com

Using a new macroeconomic model called DYNAMMICs, my colleagues and I have found that there is often a significant growth effect for the economy attached to investing in mitigation measures like dams and drought resistant crops, which is commonly underestimated in traditional models. One reason for this is the focus of other models on only the first, direct dividend. We specifically looked into the examples of Tanzania and Zambia, which show that governments and other stakeholders in developing countries can spur economic growth by investing in DRR measures, thus increasing future earnings and creating a safe environment for investments into other economic activities.

In Tanzania and Zambia, floods affect tens of thousands of people each year (on average 45,000 or .08% of the population in Tanzania and 20,000 or .11% of the population in Zambia). Droughts have more widespread consequences and already affect 11.8% of the population in Tanzania and 19% of Zambians who often lose all or parts of their harvest. This poses an imminent threat to food security in countries where substantial shares of the population rely on subsistence farming as their primary source of income. Given the effects of climate change, these numbers and their ramifications are bound to become ever more pressing issues. However, policymakers, institutions, enterprises, and individuals tend to underinvest in adaption measures.

A promising avenue for demonstrating the potential of DRR investments is offered by including all economic growth effects they invoke into policy analysis, thus showing that besides risk reduction and post-disaster mitigation of destruction, investing in DRR measures can help countries achieve many of their other development goals as well.

We tend to only think of the first dividend of DRR investments, the direct effects of which stop people from being immediately affected by disasters. In the case of Tanzania and Zambia, we examined, among others, the benefits of constructing additional dams. The direct benefits of dams lie in the safeguarding of livelihoods, infrastructure, housing, and agricultural production. These are seen as the first dividend, called the ex-post damage mitigation effect. There are however also additional co-benefits.

In both Tanzania and Zambia, large shares of the population are heavily dependent on agriculture, which makes the introduction of drought-resistant crop varieties such an additional benefit. These crop varieties do not only help farmers preserve their yields in times of disastrous droughts, but additionally support farmers by generating higher yields, even in the absence of disaster. This effect is boosted by the lowered risk for the loss of crops, which spurs investment into farming activities and inputs. Farmers who do not fear losing their entire harvest can, and generally will, invest more into the production of this crop – an example of the second type of dividend, the ex-ante risk reduction effect. This type of economically beneficial effect materializes regardless of the onset of disaster.

The same is true for the third type of dividend, the co-benefit production expansion effect, which is especially relevant for the advantages of dams. The power generation capability of dams, leads to much larger economic gains than the two other dividends combined. In countries such as those at hand with frequent power cuts and comparably low levels of electrification, especially in rural areas, the additional electricity generated can lead to particularly pronounced positive effects by supplying economic actors with access to power. In other scenarios, the provision of ecosystem services is also an important effect falling into this category.

The results we obtained using the DYNAMMICs model are promising: Constructing only two additional dams leads to a 0.3% increase of GDP growth in Tanzania for the next 30 years (0.2% in Zambia) with results largely (97%) driven by the co-benefit production expansion effect. Similarly, the introduction of drought resistant crops and exposure management (i.e., land use restrictions) significantly boost economic growth perspectives. Finally, introducing insurance is a driver for a reduction in the variance of GDP growth, which helps to reduce uncertainty for everyone in the economy. Modeling in such a fashion is therefore an important means of weighing policy options for DRR against each other and for determining optimal levels of investment.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 14, 2020 | China, Environment, Food & Water, Water, Women in Science

By Maryna Strokal, Department of Environmental Sciences, Water Systems and Global Change, Wageningen University and Research, The Netherlands

Maryna Strokal discusses a new integrated approach to finding cost-effective solutions for nutrient pollution and coastal eutrophication developed with IIASA colleagues.

© Huy Thoai | Dreamstime.com

Have you ever wondered why the water in some rivers appear to be green? The green tinge you see is due to eutrophication, which means that too many nutrients – specifically nitrogen and phosphorus – are present in the water. This happens because rivers receive these nutrients from various land-based activities like run-off from agricultural fields and sewage effluents from cities. Rivers in turn export many of these nutrients to coastal waters, where it serves as food for algae. Too many nutrients, however, cause the algae and their blooms to grow more than normal. Because algae consumes a lot of oxygen, this lowers the available oxygen supply in the water, killing off fish and other marine life. Some algae can also be toxic to people when they eat seafood that have been exposed to, or fed on it. Polluted river water on the other hand, is unfit for direct use as drinking water, or for cooking, showering, or any of our other daily needs. Before we can use this water, it needs to be treated, which of course costs money.

To better understand and address these issues, I worked with colleagues from IIASA, Wageningen University, and China to develop an integrated approach to identify cost-effective solutions (read cheapest) to reduce river pollution and thus coastal eutrophication. Our integrated approach takes into account human activities on land, land use, the economy, the climate, and hydrology. We implemented the new approach for the Yangtze Basin in China.

The Yangtze is the third longest river in the world and exports nutrients from ten sub-basins to the East China Sea, where the coast often experiences severe eutrophication problems that may increase in the coming years. The Chinese government has called for effective actions to ensure clean water for both people and nature.

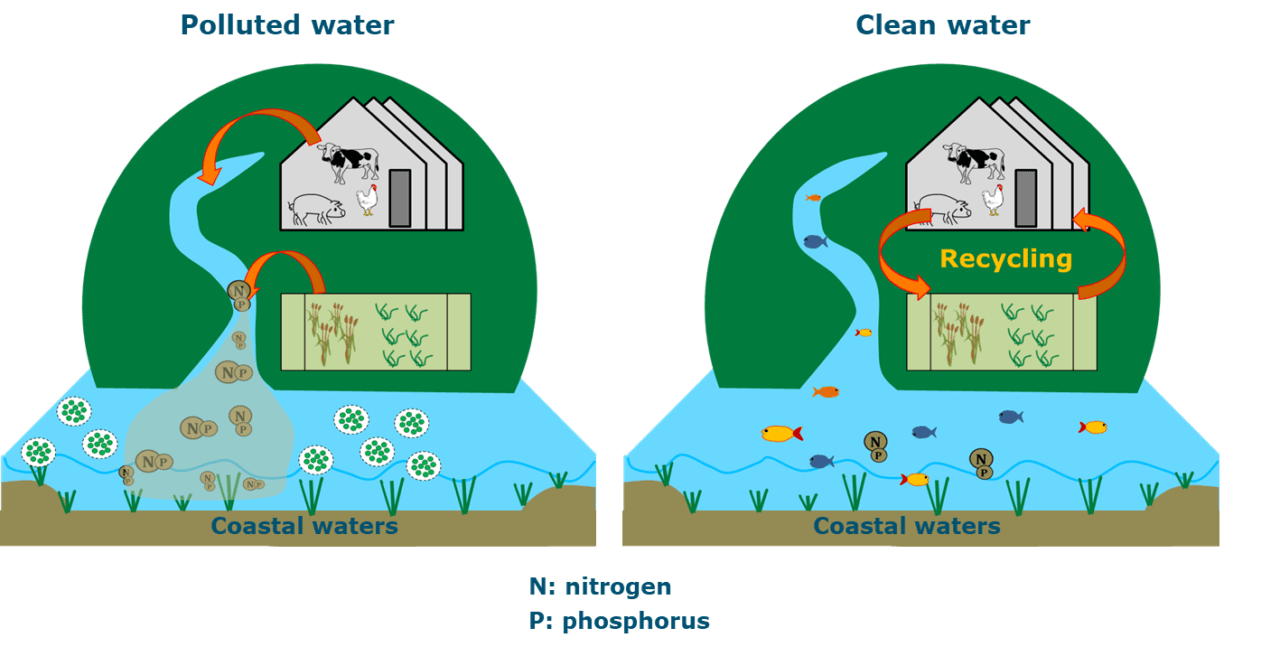

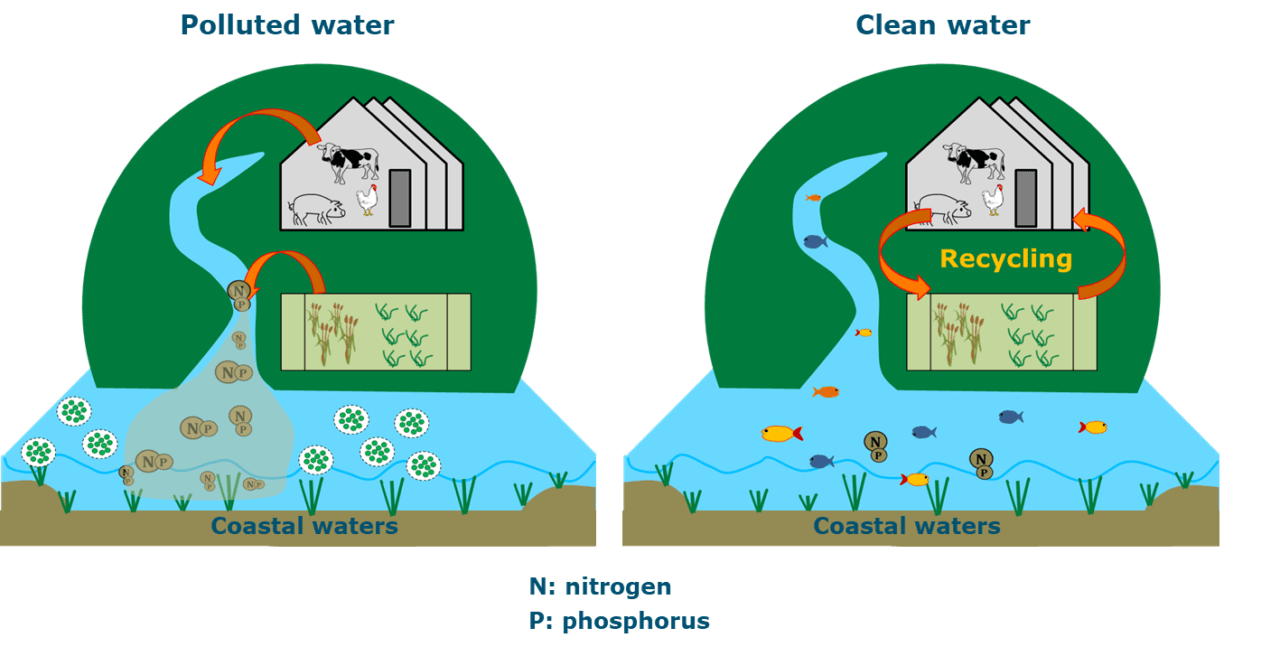

In our paper on this work, which was recently published in the journal Resources, Conservation, and Recycling, my colleagues and I conclude that reducing more than 80% of nutrient pollution in the Yangtze will cost US$ 1–3 billion in 2050. This cost might seem high, but it is actually far below 10% of the income level in the Yangtze basin. We also identified an opportunity in the negative or zero cost range, which would result in a below 80% reduction in nutrient export by the Yangtze. This negative or zero cost alternative involves options to recycle manure on land and reduce the use of chemical fertilizers (Figure 1). More recycling means that farmers will buy less chemical fertilizers and potential savings can then compensate for the expenses related to recycling the manure. We also illustrated the costs that would be involved for ten sub-basins to reduce their nutrient export to coastal waters.

Figure 1. Summarized illustration of eutrophication causes and cost-effective solutions for reducing nutrient export by Yangtze and thus coastal eutrophication in the East China Sea in 2050.

Recycling manure on cropland is an important and cost-effective solution for agriculture in the sub-basins of the Yangtze River (Figure 1). Manure is rich in the nutrients that crops need, and opting for this alternative instead of chemical fertilizers avoids loss of nutrients to rivers, and thus ultimately to coastal waters. Current practices are however still far from ideal, with manure – and especially liquid manure – often being discharged into water because crop and livestock farms are far away from each other, which makes it practically and economically difficult to transport manure to where it is needed. Another reason is the historical practice of farmers using chemical fertilizers on their crops – it is simply how they are used to doing things. Unfortunately, the amounts of fertilizers that farmers apply are often far above what crops actually need, thus leading to river pollution.

The Chinese government are investing in combining crop and livestock production, in other words, they are creating an agricultural sector where crops are used to feed animals and manure from the animals is in turn used to fertilize crops. Chinese scientists are working with farmers to implement these solutions.

In our paper, we showed that these solutions are not only sustainable, but also cost-effective in terms of avoiding coastal eutrophication. We invite you to read our paper for more details.

References

Strokal M, Kahil T, Wada Y, Albiac J, Bai Z, Ermolieva T, Langan S, Ma L, et al. (2020). Cost-effective management of coastal eutrophication: A case study for the Yangtze River basin. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 154: e104635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104635.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 21, 2019 | Air Pollution, Environment, Food & Water, Indonesia, Women in Science

By Adriana Gómez-Sanabria, researcher in the IIASA Air Quality and Greenhouse Gases Program

Adriana Gómez-Sanabria discusses the results of a new study that looked into the impacts of implementing various technologies to treat wastewater from the fish processing industry in Indonesia.

© Mikhail Dudarev | Dreamstime.com

To reduce water pollution and climate risks, the world needs to go beyond signing agreements and start acting. Translating agreements and policies into action is however always much more difficult than it might seem, because it requires all players involved to participate. A complete integration strategy across all sectors is needed. One of the advantages of integrating all sectors is that it would be possible to meet different objectives, for example, climate and water protection goals in this case, with the same strategy.

I was involved in a study that assessed the impacts of implementing various technologies to treat wastewater from the fish processing industry in Indonesia when involving different levels of governance. This study is part of the strategies that the government of Indonesia is evaluating to meet the greenhouse gas mitigation goals pledged in its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), as well as to reduce water pollution. Although Indonesia has severe national wastewater regulations, especially in the fish processing industry, these are not being strictly implemented due to lack of expertise, wastewater infrastructure, budgetary availability, and lack of stakeholder engagement. The objective of the study was to evaluate which technology would be the most appropriate and what levels of governance would need to be involved to simultaneously meet national climate and water quality targets in the country.

Seven different wastewater treatment technologies and governance levels were included in the analysis. The combinations included were: 1) Untreated/anaerobic lagoons – where untreated means wastewater is discharged without any treatment and anaerobic lagoons are ponds filled with wastewater that undergo anaerobic processes – combined with the current level of governance. 2) Aeration lagoons – which are wastewater treatment systems consisting of a pond with artificial aeration to promote the oxidation of wastewaters, plus activated sludge focused solely on water quality targets with no coordination between water and climate institutions. 3) Swimbed, which is an aerobic aeration tank focusing mainly on climate targets assuming no coordination between institutions. 4) Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) technology, which is an anaerobic reactor with gas recovery and use followed by Swimbed, and 5) UASB with gas recovery and use followed by activated sludge, which is an aerobic treatment that uses microorganisms forming particles that clump together. Both, 4 and 5 assume vertical and horizontal coordination between water and climate institutions at national, regional, and local level. It is important to notice that the main difference between 4 and 5 is the technology used in the second step. Two additional combinations, 6 and 7, are also proposed including the same technological combinations of 4 and 5, but these include increasing the level of governance to a multi-actor coordination level. The multi-actor level includes coordination at all institutional levels but also involves academia, research institutes, international support, and other stakeholders.

Our results indicate that if the current situation continues, there would be an increase of greenhouse gases and water pollution between 2015 and 2030, driven by the growth in fish industry production volumes. Interestingly, the study also shows that focusing only on strengthening capacities to enforce national water policies would result in greenhouse gas emissions five times higher in 2030 than if the current situation continues, due to the increased electricity consumption and sludge production from the wastewater treatment process. The benefit of this strategy would be positive for the reduction of water pollution, but negative for climate change mitigation. From our analyses of combinations 2 and 3 we learned that technology can be very efficient for one purpose but detrimental for others. If different institutions are, for example, responsible for water quality and climate change mitigation, communication between the institutions is crucial to avoid trade-offs between environmental objectives.

Furthermore, when analyzing different cooperation strategies together with a combination of diverse sets of technologies, we found that not all combinations work appropriately. For instance, improving interaction just within and between institutions does not guarantee proper selection and application of technologies. In this case, the adoption of the technology is not fast enough to meet the targets proposed in 2030, thus resulting in policy implementation failures. Our analyses of combinations 4 and 5 showed that interaction within and between national, regional, and local institutions alone is not enough to prevent policy failure.

Finally, a multi-actor cooperation strategy that includes cooperation across sectors, administrative levels, international support, and stakeholders, seems to be the right approach to ensure selection of the most appropriate technologies and achieve policy success. We identified that with this approach, it would be possible to reduce water pollution and simultaneously decrease greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity required for wastewater treatment. Analyzing combinations 6 and 7 revealed that multi-actor governance allows to simultaneously meet climate and water objectives and a high chance to prevent policy failure.

In the end, analyses such as the one shown here, highlight the importance of integrating and creating synergies across sectors, administrative levels, stakeholders, and international institutions to ensure an effective implementation of policies that provide incentives to make careful choices regarding multi-objective treatment technologies.

Reference:

Gómez-Sanabria A, Zusman E, Höglund-Isaksson L, Klimont Z, Lee S-Y, Akahoshi K, Farzaneh H, & Chairunnisa (2019). Sustainable wastewater management in Indonesia’s fish processing industry: bringing governance into scenario analysis. Journal of Environmental Management (Submitted).

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 17, 2019 | Alumni, IIASA Network

Monika Bauer, IIASA Network and Alumni Officer, interviewed alumnus Dennis Meadows during his recent visit to IIASA.

Dennis Meadows with colleagues in the IIASA Water & RISK Programs © Monika Bauer | IIASA

“It’s a great pleasure to be back at IIASA because the institute really had a big impact on my professional life,” said Dennis Meadows, coauthor of the seminal book Limits to Growth, after his lecture to IIASA staff during a recent visit to the institute. “I came to IIASA, and it gave me so many new ideas and contacts. It became the fuel for my professional activities for a long time.”

Meadows visited the IIASA Energy Program in 1977 when Roger Levien was director, and he says that Levien greatly impacted the way he viewed problems. In his lecture titled, Lessons from 50 years of model-based policy advocacy, he pointed out that Levien looked at problems as universal or global, and that he uses the criteria Levien passed on to him in what he calls “problem selection” to this day. Meadows also spent some time at the institute from 1983-1984 when C.S. Buzz Holling was director.

During his lecture, Meadows highlighted the idea of using the concept of an “invisible college” as a strategy to implement academic work. He explained that an “invisible college” usually constitutes a group of about 50 people connected with an issue, who, while they do not necessarily all have to agree on the issue or do the same work, can collectively come up with a solution.

© Dennis Meadows

Meadows created his version of an invisible college through the Balaton Group, a global network for collaboration on systems and sustainability that he founded in 1982. He says that the network is meant to “connect and empower people who will go back home and do good things”. Meadows stopped by IIASA on his way to the group’s annual retreat in at Lake Belaton in Hungary, where 50 leading scientists, teachers, consultants, writers, and managers annually get together to discuss topical issues on their own costs. According to Meadows, this in itself shows the value individuals see in the meetings. The results of past meetings are outlined on the group’s webpage.

When asked about his key messages for IIASA, Meadows’ answers focused on the institute’s alumni network and exploring a deeper understanding of resilience.

“The incredible power of IIASA lies in its alumni, rather than in its models. You create the alumni network through the process of creating models. IIASA doesn’t have many models, but it has thousands of alumni. One of the first things I would look at is how to link alumni more strongly together, so they could help each other. I still have affection for the institute and respect for what it does, and I’m sure that my opinion is shared by many.”

His second take-away for IIASA concerns building a deeper expertise on resilience. “Sustainable development is something that is hard to realize, while there is no doubt that shocks will continue to occur, and there is no unified theory in resilience yet. In my opinion, IIASA has an opportunity to tap into a huge legacy of understanding that goes back to Buzz Holling’s work.”

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.