Dec 16, 2021 | Alumni, Demography, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Fanni Daniella Szakal, 2021 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Can we lift people out of energy poverty while simultaneously reducing carbon dioxide emissions? 2021 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant Camille Belmin tried to tackle this seemingly contradictory issue by including fertility in the equation and estimating the conditions where an increase in energy access would reduce demand through decreasing population sizes.

© Photopassion77 | Dreamstime.com

About every third person in the world today doesn’t have access to clean cooking fuels and 1 in 10 are without electricity, predominantly in the Global South. Increasing energy access will not only improve the quality of life for many, but it will also propel us towards achieving some of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) such as SDG3, Good Health and Wellbeing, and SDG7, Access to Clean and Affordable Energy.

The downside of increasing energy access is the surge in carbon dioxide emissions that will likely follow. Although populations with low energy access emit only a small share of global carbon emissions compared to countries in the Global North, an increase in energy provisioning would still put more pressure on the climate crisis. But, what if we could increase energy access and decrease emissions at the same time while tackling a few more SDGs in the process, such as SDG5, Gender Equality and SDG13, Climate Action?

Camille Belmin, a participant in the 2021 YSSP aimed to do just that. As a PhD Student at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and at the Humboldt University of Berlin, Belmin focuses on the relationship between energy access and women’s fertility. In a previous study covering 43 countries around the globe, she found evidence that higher access to electricity and modern cooking fuels was associated with women having fewer children.

“With more access to energy, instead of, for example, picking up firewood for many hours a day, women are able to spend more time on education and employment. Energy access also lowers the need for child labor and reduces child mortality through reduction of indoor air pollution and improved healthcare. This often leads to women becoming more empowered and gives them agency over their reproductive choices, leading to a fertility decline,” says Belmin.

In her YSSP project, Belmin took the energy-fertility relationship a step further: she wanted to explore if an initial boost in energy access could lead to a decline in energy demand in the long term through reduced population sizes, both increasing the quality of life and reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

“I hope that by showing that universal access to energy can also have benefits for sustainability, I can encourage investments in modern energy access in countries where basic services are lacking,” she notes.

To find out under which conditions increasing energy access will lead to a decrease in energy demand, Belmin used a microsimulation model of population projection. Under different energy access scenarios, the model follows each individual in a hypothetical population through life events, such as birth, death, and gaining access to education and electricity, while calculating their total energy consumption. She hoped to find a scenario with net savings in energy demand, in other words, a scenario where the more you give, the more you get.

Setting up the model was a new challenge for Belmin ̶ while many scientific fields have been using microsimulation for a long time, applying it to population modeling based on energy access is a novelty. The potential benefits and positive implications of the work were however well worth the difficulty.

The study focused on population simulations in Zambia, where Belmin collaborates with an NGO that aims to finance education for girls through carbon credits, building on the idea that education will lead to lower population sizes and decreased emissions in the future.

“Because of patriarchal structures, women are often bound to household chores, making the lack of energy a huge burden,” says Belmin. “This research is very important to me as a woman, or just as a human, as it seems that providing modern energy services might be a way for women to have more choice and freedom in their lives.”

Further information:

Belmin, C. (2021). Introducing the energy-fertility nexus in population projections: can universal access to modern energy lead to energy savings? IIASA YSSP Report. Laxenburg, Austria: IIASA [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17688]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 26, 2021 | Demography, Environment, Finland, IIASA Network, Poverty & Equity

By Venla Niva, DSc researcher with the Water and Development Research Group, School of Engineering, Aalto University, Finland

Venla Niva shares insights from a recent article exploring the interplay of environmental and social factors behind human migration. The project was carried out in collaboration with Raya Muttarak from the IIASA Population and Just Societies Program.

© Irina Nazarova | Dreamstime.com

Environmental migration has gained increasing attention in the past years, with recent climate reports and policy documents highlighting an increase in environmental refugees and migrants as one of the potential effects of the warming globe. Policymaking is dominated by a narrative that portrays environmental migration as a security threat to the “Global North”. Meanwhile, researchers around the world have put enormous efforts into understanding environmental migration and what is driving it. Yet, the causes and effects of environmental migration remain under debate.

In our latest paper, we extend the understanding of environmental migration by looking into how environmental and societal factors interacted in places of excess out- or in-migration between 1990 and 2000. We found that understanding these interactions is key for understanding migration drivers. Ultimately, migration is based on human decision-making, and in our view “simply cannot and should not be studied without the inclusion of the societal dimension: human capacity and agency.” Our findings were both expected and, to a certain degree, surprising.

Our results show that the majority of global migration takes place in areas with rather similar profiles. It is known that migration mostly occurs over short distances, and that internal migration – in other words, people moving around in their own country – outplays international migration – people moving between countries – by significant numbers globally. This, however, shows that the characteristics of these areas are alike too. High environmental stress coupled with low-to-moderate human capacity characterized these areas at both ends of migration. Such characteristics portray a combination of variables with a high degree of drought and water risks, natural hazards, and food insecurity, but low levels of income, education, health, and governance.

We found that income was the best variable to explain the variation of net-negative and net-positive migration in around half of the countries, globally, confirming that income is a good predictor of migration. This is interesting in two ways. According to traditional migration theories, income disparity between regions is seen as the primary driver for migration. Yet, income only dominated the other variables in half of the countries we examined. Education and health were especially important in areas with more out-migration than in-migration. Drought and water risks were important explaining factors in many countries, but were outranked by societal factors such as income, health, education, and governance in the majority of countries.

In light of our research, we would like to point out that it is unlikely that environmental factors alone would be responsible for migration. Instead, the role of human agency is vital. Investments in building human capacity have two-fold benefits: First, higher human capacity facilitates not only local adaptation to changes in the environment, but also adaptation at the destination in case of migrating. Second, protecting ecosystems and the environment helps to mitigate and adapt to climate and environmental change in areas with high environmental stress, which is again crucial for maintaining livelihoods and a good life at both ends of migration.

Environmental migration is often portrayed by the media as a catastrophic phenomenon. Our study confirms that migration drivers are a result of the interactions between socioeconomic and environmental factors and that human capacity plays a central role in both enabling the migration process and adaptation at the place of destination.

Further info:

Niva, V., Kallio, M., Muttarak, R., Taka, M., Varis, O., & Kummu, M. (2021). Global migration is driven by the complex interplay between environmental and social factors. Environmental Research Letters DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac2e86. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17507]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 20, 2021 | COVID19, Poverty & Equity, Risk and resilience, Women in Science

By Benigna Boza-Kiss, Shonali Pachauri, and Caroline Zimm from the IIASA Transformative Institutional and Social Solutions Research Group

Benigna Boza-Kiss, Shonali Pachauri, and Caroline Zimm explain how COVID-19 has impacted the poor in cities and what can be done to increase the future resilience of vulnerable populations.

© Manoej Paateel | Dreamstime.com

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought a halt to life as we knew it. We have been restrained in our activities and freedoms, forced to stay indoors at home, to cancel travel plans, and to transfer meetings to an online space, where most of us have also celebrated birthdays and other important life events that should have been in person with our loved ones. These changes have impacted many aspects of our comfort, our social wellbeing, as well as our financial situations, but it has also brought existing inequalities and poverty into the spotlight.

The risks of the pandemic and restrictions following containment measures have been felt most acutely by the poor, the vulnerable, those in the informal sector, and those without savings and safety nets. The suffering of women in the health sector, school children in households without electricity and internet, workers in the informal sector that don’t have the option to telework, crowds living in slums – to name just a few examples of vulnerable groups – have become glaringly visible to all. These people have had to adapt to new rules and conditions when they were living on the edge even before the pandemic.

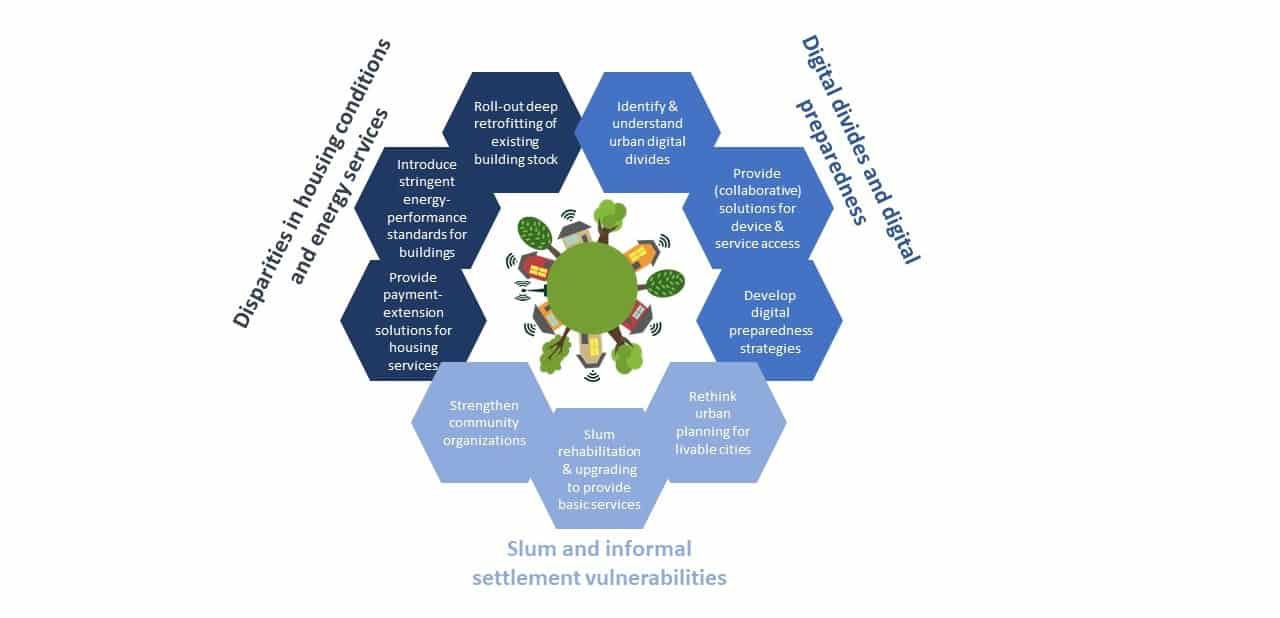

In a new perspective piece published in the journal Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, we explored how aspects related to access to shelter/housing, modern energy, and digital services in cities have influenced the poor and what can be done to increase the future resilience of vulnerable populations.

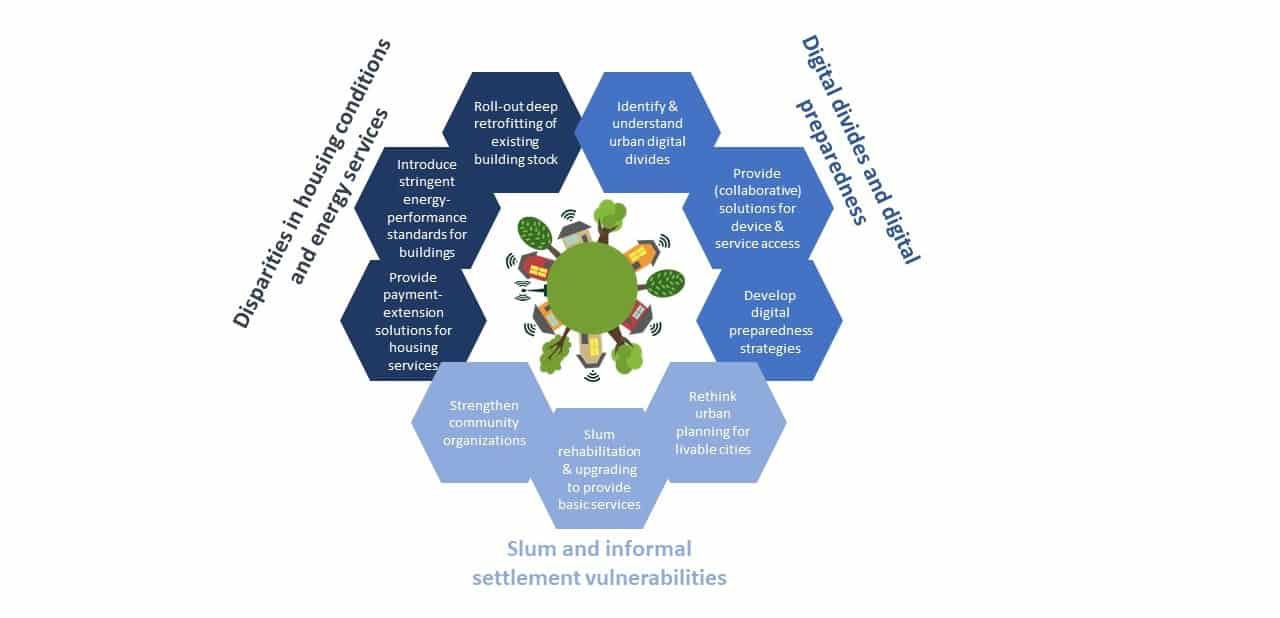

We described three ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic and related containment measures have exacerbated urban inequalities, and identified how subsequent recovery measures and policy responses could redress these.

First, lockdowns amplified urban energy poverty. Staying at home has meant increased energy use at home. For the poor, who already struggle with utility costs, and typically live in low energy quality buildings, these services have become even more unaffordable. These populations also shoulder a higher burden of poor health, for example, higher incidence of respiratory problems, with poor or inadequate ventilation and insulation increasing their risk of infection even more.

Second, preexisting digital divides have surfaced, even within well-connected cities. Multiple barriers limit digital inclusion: access to digital technologies due to high costs (for devices, internet access, and electricity connections), and unreliable services (again both for electricity and internet), as well as low digital literacy and support. This lack of adequate digital service access is contributing to these populations falling further behind during lockdowns as they miss out on education and income.

Third, slum dwellers in the world’s cities have been particularly hard hit, because of precarious and overcrowded housing conditions, lack of basic infrastructure and amenities, and a high concentration of the socioeconomically disadvantaged, resulting in even more negative consequences of lockdown measures. With many slum inhabitants working in the informal sector, many have been left either without jobs and income, or have been compelled to work in precarious and unsafe conditions to survive. The loss of income has also had knock-on effects, making payments of regular expenditures for rent, water, electricity, and other utility services difficult. Women within these settlements have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, as they are over represented in the informal economy, and more likely to be engaged in invisible work, such as home-based or domestic and care work.

Recovery measures need to ensure immediate relief, but also point towards long-term solutions that contribute to the redistribution of wealth and new urban development, while also increasing resilience to the current and future pandemics or other disasters. There are tested measures that should be reemphasized.

Urban green recovery plans that include large-scale home renovation programs could ensure warm, healthy homes, and affordable energy bills for all. In the shorter-term, alleviation of payment defaults on the rents and utility bills of the energy poor should continue. In parallel, urban digital preparedness, more equal access to the virtual delivery of essential services, and provision of opportunities for virtual working and education for all in the future, need attention.

COVID-19 can be a wake up call to increase efforts to close the digital divide and push for structural change. The crisis has increased the urgency to redesign and improve informal settlements and provide adequate and efficient services that address the diverse needs of poor urban residents. This requires partnerships between urban municipalities, planners, and stakeholders, as well as strengthening local communities for inclusive planning strategies. More immediately, it is necessary to provide direct support to slum and informal settlement populations in terms of income support, adequate nutrition, energy, water, and other basic infrastructure and services.

All in all, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a “test of societies, of governments, of communities, and of individuals”. Digital technologies, home renovation, and slum rehabilitation are the means, rather than the end to improve conditions for all, but if specifically targeted to the poor and most deprived, such measures can reduce inequalities and increase resilience.

All in all, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a “test of societies, of governments, of communities, and of individuals”. Digital technologies, home renovation, and slum rehabilitation are the means, rather than the end to improve conditions for all, but if specifically targeted to the poor and most deprived, such measures can reduce inequalities and increase resilience.

Reference:

Boza-Kiss, B., Pachauri, S., & Zimm, C. (2021). Deprivations and Inequities in Cities Viewed Through a Pandemic Lens. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 3 e645914. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17121]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 12, 2021 | Poverty & Equity, Risk and resilience, Sustainable Development

by Viktor Roezer | Swenja Surminski | Finn Laurien | Colin McQuistan | Reinhard Mechler | Anna Svensson

Disaster Risk Reduction investments bring a wide variety of benefits, including economic, ecological, and social, but in practice these multiple resilience dividends are often not included in investment appraisals or are not recognized by those making funding decisions. How do we change this?

Research led by the London School of Economics and Political Science with IIASA and Practical Action published in the Working Paper Multiple resilience dividends at the community level: A comparative study on disaster risk reduction interventions in different countries highlights the need for an integrated decision-making framework to overcome the challenges.

The negative effects of disasters on people and communities are varied and far reaching, and will only get worse as climate change make floods and other natural hazards more frequent, severe, and unpredictable. Disasters lead to loss of lives, assets, and livelihoods, they undermine or destroy development progress. Since 2000 climate related hazards have caused $2.2 trillion of losses and damages and have affected approximately 3.9 billion people globally.

With investments in disaster risk reduction (DRR), where community resilience is enhanced these negative impacts can be reduced and savings can be made. It’s more cost effective to invest in pre-event resilience than post-event response and recovery.

So why is disaster risk reduction so difficult to finance?

The problem with estimating the direct benefit of disaster risk reduction interventions is that you only see the benefits when an event which would otherwise have turned into a disaster occurs and is successfully mitigated.

This makes cost-benefit analysis and other decision-making methods difficult to carry out, and makes the costs of doing something more aligned to the probability of the event, rather than the lives and economic costs saved, thus changes to policy and practice are slow to materialize.

What are the multiple dividends of resilience?

The multiple dividends of resilience refer to positive socioeconomic outcomes generated by, and co-benefits of, an intervention beyond, and in addition to, risk reduction.

It’s an approach aimed at making DRR investments more attractive as the multiple dividends of an investment may help identify win-win-win situations (as well as trade-offs), even if no hazard event occurs. Co-benefits can be intended, or unintended.

As framed by the Triple Resilience Dividend concept these benefits can be divided into three categories:

1. The avoided losses and damages in case of a disaster

For example, how bio-dykes in Nepal prevent river bank erosion, which reduces the risk of flooding, and associated sand deposits that ruin the fertility of agricultural land.

2. The economic potential of a community that is unlocked through the intervention

This includes ecosystem-based adaptation solutions in Vietnam where mangrove plantations create new habitats for fish, leading to improved livelihood opportunities for those making their living from fishing.

3. Other development co-benefits

Transition to solar stoves in rural Afghanistan does not only protect natural capitals from degradation, but also empowers women and girls, reduces in-house smog pollution, and fosters technological innovations.

Rongali next to his community’s bio-dyke. Photo by Sanjib Chaudhary, Practical Action.

What are the challenges?

The triple resilience dividend approach is often linked to new and innovative solutions like ecosystem based adaptation, where the benefits can be wider, but when and how they will materialize is more uncertain than with traditional, hard infrastructure solutions.

Although many developing countries have policies that align DRR, climate change adaptation, and sustainable development, sadly, in practice, local decision makers assume that multiple resilience dividends will only accumulate over the long term. This often leads them to select traditional, hard infrastructure solutions that offer quick and more visible protection.

We need more success stories. Pilot interventions can be shared and shown to community members and decision makers to overcome their skepticism but this require better and more comprehensive evidence than we have today.

We also lack decision-making frameworks that can include and monitor multiple resilience dividends. Frameworks that support planners as they navigate the decision-making process, and help generate the evidence needed.

Community members in the Peruvian Andes working at a local tree nursery. Photo by Giorgio Madueño , Practical Action

How do we overcome these challenges?

The solution suggested in Multiple resilience dividends at the community level: A comparative study on disaster risk reduction interventions in different countries is an integrated decision-making framework that allows to systematically include, appraise, implement, and evaluate individual resilience dividends at each stage of the decision-making process.

Application and relevance matters.

As we suggest, instead of maximizing resilience dividends based on a specific, one dimensional, metric (e.g., monetary benefits) decision-making approaches need to identify those dividends that are most needed and demanded by the community and the solutions, novel or local in nature, best suited to generate these.

A structured approach in combination with participatory decision making allows for a tailored approach where community buy-in is achieved by prioritizing the resilience dividend(s) that matter most to them, while at the same time contributing to the evidence base for multiple resilience dividends.

This is urgently needed to highlight the fundamental challenges with the existing planning and decision-making system and therefore generate demand to deliver more effective solutions at scale.

Cleaning waste from river in Penjaringan Urban Village, Jakarta, Indonesia. Photo by Piva Bell, Mercy Corps.

Read the working paper this blog is based on here.

This blog post first appeared on the Flood Resilience Portal. Read the original post here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 2, 2021 | Environment, Poverty & Equity, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

By Prakash Khadka, IIASA Guest Research Assistant and Wei Liu, Guest Research Scholar in the IIASA Equity and Justice Research Group

Prakash Khadka and Wei Liu explain how unbridled, unplanned infrastructure expansion in Nepal is increasing the risk of landslides.

Worldwide, mountains cover a quarter of total land area and are home to 12% of the world’s population, most of whom live in developing countries. Overpopulation and the unsustainable use of these fragile landscapes often result in a vicious cycle of natural disaster and poverty. Protecting, restoring, and sustainably using mountain landscapes is an important component of Sustainable Development Goal 15 ̶ Life on Land ̶ and the key is to strike a balance between development and disaster risk management.

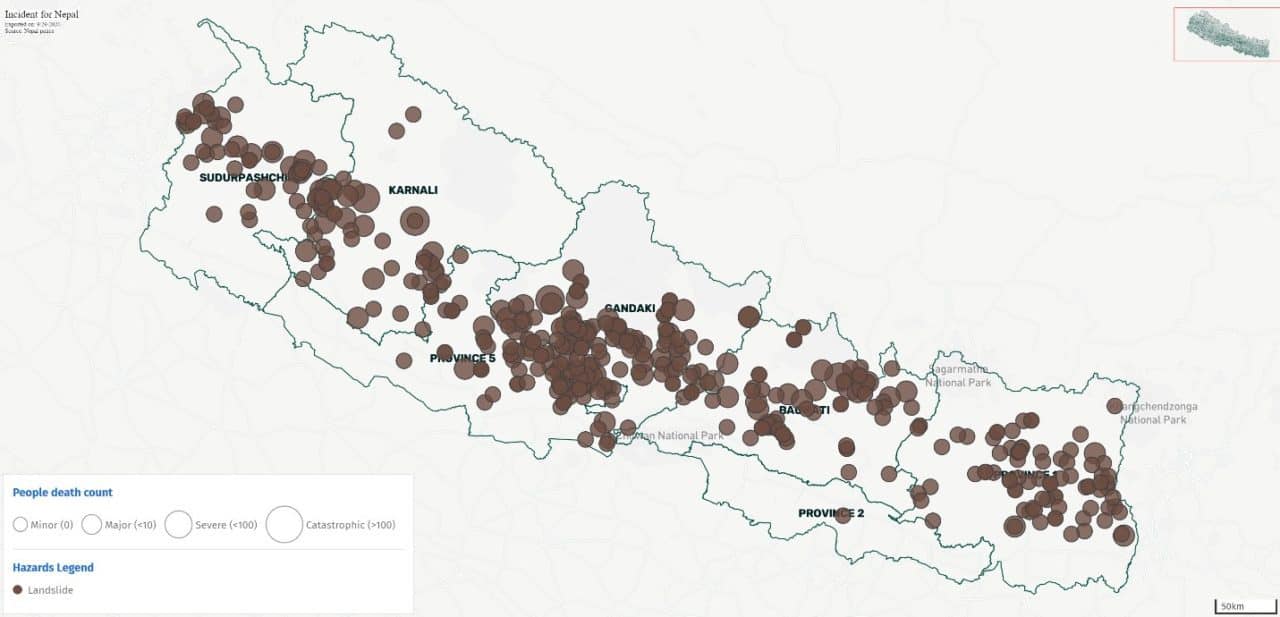

Nepal is among the world’s most mountainous countries and faces the daunting challenge of landslides and flood risk. Landslide events and fatalities have been increasing dramatically in the country due to a complex combination of earthquakes, climate change, and land use, especially the construction of informal roads that destabilize slopes during the monsoon.

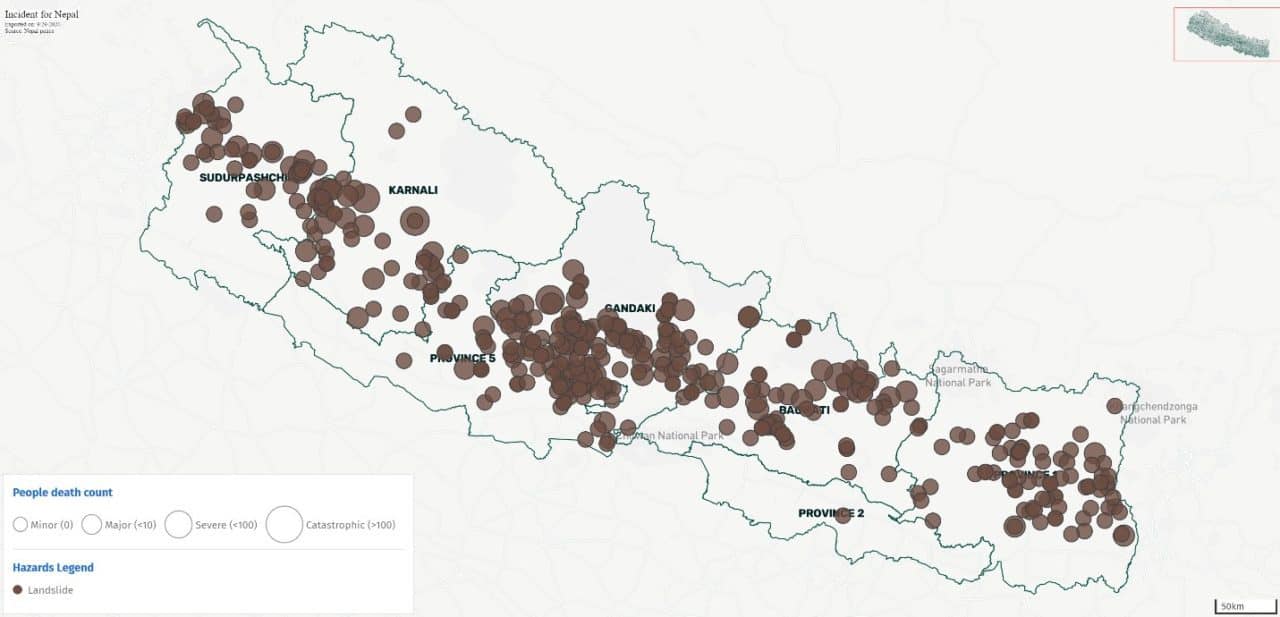

According to Nepal government data, 476 incidents of landslides and 293 fatalities were recorded during the 2020 monsoon season – the highest number in the last ten years, mostly triggered by high-intensity rainfall – a trend which is increasing due to climate variations. According to one study, by mid-July 2020, the number of fatal landslides for the year had already exceeded the average annual total for 2004–2019.

Figure 1: A map of landslide events in Nepal from June to September 2020. Source: bipadportal.gov.np

Landslides are not a new phenomenon in the country where hills and mountains cover nearly 83% of the total land area. While being destructive, landslides are complex natural processes of land development. The Gangetic plain, situated in the foothills of the Himalayas, was formed by the great Himalayan river system to which soil is continually added by landslides and deposited at the base by rivers. Mountain land changes via natural geo-tectonic and ecological processes has been happening for millions of years, but fast population growth and climate change in recent decades substantially altered the fate of these mountain landscapes. Road expansion, often in the name of development, plays a key role.

Many mountain areas in Nepal are physically and economically marginalized and efforts to improve access are common. Poverty, food insecurity, and social inequity are severe, and many rural laborers opt to migrate for better economic opportunities. This motivates road network expansion. Since the turn of the century, Nepalese road networks has almost quadrupled to the current level of ~50 km per 100 km2, among which rural roads (fair-weather roads) increased more than blacktop and gravel roads.

Figure 2: Mountains carved just above Jay Prithvi Highway in Bajhang district of Sudurpaschim province to build a road

Nepalese mountain roads are treacherous and subject to accidents and landslides. Rural roads, which are often called “dozer roads”, are constructed by bulldozer owners in collaboration with politicians at the request of communities (also as part of the election manifesto in which politicians promised road access in exchange for votes and support to win), often without proper technical guidance, surveying, drainage, or structural protection measures. In addition, mountains are sometimes damaged by heavy earthmovers (so-called “bulldozer terrorism”) that cut out roads that lead from nowhere to nowhere, or where no roads are needed, at the expense of economic and environmental degradation. Such rapid and ineffective road expansion happens throughout the country, particularly in the middle hills where roads are known to be the major manmade driver of landslides.

To tackle these complexities, we need to rethink how we approach development in light of climate change. This has to be done with sufficient investigation into our past actions. The Nepalese Community forestry management program, which emerged as one of the big success stories in the world, encompasses well defined policies, institutions, and practices. The program is hailed as a sustainable development success with almost one-third of the country’s forests (1.6 million hectares) currently managed by community forest user groups representing over a third of the country’s households. Another successful example is the innovation of ropeways and its introduction in the Bhattedanda region South of Kathmandu. The ropeways were instrumental in transforming farmers’ lives and livelihoods by connecting them with markets. Locals quickly mastered the operation and management of the ropeway technology, which was a lifesaver following the 2002 rainfall that washed away the road that had made the ropeway redundant until then.

These two examples show that it is possible to generate ecological livelihoods for several households in Nepal without adversely affecting land use and land cover, which in turn contributes to increased landslide risk in the country, as mentioned above.

A rugged landscape is the greatest hindrance to the remote communities in a mountainous country like Nepal. It cannot be denied that the country needs roads that serve as the main arteries for development, while local innovations like ropeways can well complement the roads with great benefits, by linking remote mountain villages to the markets to foster economic activities and reduce poverty. Such a hybrid transportation model is more sustainable economically as well as environmentally.

It is a pity that despite strong evidence of the cost-effectiveness of alternative local solutions, Nepal’s development is still mainly driven by “dozer constructed roads”. Mountain lives and livelihoods will remain at risk of landslides until development tools become more diverse and compatible.

References:

- Gyawali, D. (Ed.), Thompson, M. (Ed.), Verweij, M. (Ed.). (2017). Aid, Technology and Development. London: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315621630

- Gyawali, Dipak; Dixit, Ajaya; Upadhya, Madhukar (2004). Ropeways in Nepal.

- Petley, D. N. (2020). The deadly start to the monsoon season in Nepal – The Landslide Blog – AGU Blogosphere. The Landslide Blog. https://blogs.agu.org/landslideblog/2020/07/24/nepal-2020/

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.