Oct 22, 2020 | Climate Change, Energy & Climate, Science and Policy

By Shorouk Elkobros, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Assessing energy-related choices and the behaviors of households can help us transition to a low-carbon economy. How can research provide more effective decision-making tools to policymakers for better climate change mitigation policies?

We live at a defining moment for climate change, where today’s actions affect tomorrow’s reality. Every little climate-friendly decision counts. Whether we decide to insulate our houses, put solar panels on our rooftops, or invest in energy-efficient appliances. However, our personal and energy-related decisions vary based on our awareness, age, education, income, energy provider services, social norms, culture, and many other factors. Researchers are starting to pay attention to how this diversity is not well represented in the economic models that politicians use to plan climate change policies.

@ VectorMine | Dreamstime.com

Designing policies inspired by people

Households contribute an average of 70% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Limiting global emissions requires holistic policy approaches that take households’ behaviors and lifestyle decisions into account. Adding such a dimension can potentially upscale low carbon behavioral and social changes to national and global levels, which is fundamental to tackling climate change.

Worried about the future of the planet and motivated to support policymakers in designing better climate change mitigation policies, the authors of a recent study published in the journal Environmental Modeling & Software aspired to build bridges through interdisciplinary research. The study presented a novel interdisciplinary method that aims to integrate households’ energy behavior and social dynamics in climate-energy-economy models and thus help politicians design policies inspired by people.

“I have always been interested in the science-policy-society aspect of mitigating climate change. Climate change is a collective challenge that we need to address together to come up with better solutions for future generations,” notes study lead author Leila Niamir, a researcher jointly associated with the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, Berlin and the IIASA Transitions to New Technologies Program.

Better models for a better future

Climate change mitigation policies play a pivotal role in achieving ambitious environmental targets like the Paris Agreement or the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To be able to formulate appropriate mitigation policies, decision makers need assessment tools to measure complex systems quantitatively. In the past decade, a variety of assessment tools have emerged, which have since been predominantly used to support climate change policy debates. In the study, Niamir argues that current assessment models are missing bottom-up and grassroots dynamics, they cannot project realistic variables of what households’ lifestyles and social movement are, and they therefore may not be sufficient to provide reliable information for policymakers.

There is a gap between what policymakers’ current assessment tools can offer and what social scientists and behavioral economists highlight as pro-environmental behavior and climate change mitigation movements. By adding this complex behavior and social perspective to the models, the researchers make it easier for policymakers to design future policies to accommodate different societal behaviors and lifestyles.

Niamir and her team presented a novel method for systematically upscaling grassroots dynamics by linking the best of both “top-down” macroeconomic computable general equilibrium (CGE) models and “bottom-up” empirical agent-based models (ABM). Their approach demonstrates that with computational ABM directly linked to survey data and macroeconomic CGE models, individual behavioral diversity and social influences can be considered when designing implementable and politically feasible policy options.

“We need better assessment tools to quantitatively explore the complex climate-energy-economy system, and reveal the potential of demand-side mitigation strategies. To see substantial changes, we need a mix of external interventions, from soft information policies aimed at raising awareness bottom-up, to financial incentives altering the macro landscape of energy markets and technological transitions. Only modular and integrated models can help policymakers quantitatively explore this complex system and plan for changes in the coming decades,” says Niamir.

Towards a low-carbon economy

We cannot tackle what we do not know. Pathways to a low-carbon economy future entail diminishing the growing discrepancy between mitigation policies and individual and collective behaviors. When redesigning our socio-environmental systems to mitigate climate change, we need to start looking at people as case studies rather than numbers. To transition to a low-carbon economy and accelerate decarbonization, policymakers must adopt novel models that integrate energy consumption, individual behavior, heterogeneity, and social influence into current assessment tools.

In 2019, IIASA and the Research Institute of Innovative Technology for the Earth (RITE), Japan co-organized an international workshop towards improved understanding, concepts, policies, and models of energy demand, where Niamir presented her research and received the young scientist award to continue and extend her research.

“Mitigating climate change indeed requires a massive effort from individual and social movements to advance national and international collaboration. Each individual small step towards shrinking our carbon footprint creates cascading changes in social behavior and consequently mitigates climate change,” Niamir concludes.

Reference:

Niamir L, Ivanova O, & Filatova T (2020). Economy-wide impacts of behavioral climate change mitigation: linking agent-based and computable general equilibrium models. Environmental Modelling & Software 134: e104839. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/16671]

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 2, 2020 | Climate Change, Economics, Food, Poverty & Equity

By Charlotte Janssens, guest researcher in the IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program and researcher at the University of Leuven and Petr Havlík, Acting Ecosystems Services and Management Program Director.

Charlotte Janssens and Petr Havlik write about their recent study in which they found that world trade can relieve regional impacts of climate change on food production and provide a way to reduce the risk of hunger.

© Alisali | Dreamstime.com

In a warmer world, decreasing crop yields and rising food prices are expected to strongly jeopardize the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 – ending global hunger. Climate change has consequences for food production worldwide, but there are clear differences between regions. Sufficient food is expected to remain available in the Northern hemisphere, while in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia, falling crop yields may lead to higher food prices and a sharp rise in hunger.

In our recent publication in Nature Climate Change, we find that world trade can relieve these regional differences and provide a way to reduce hunger risks under climate change. For example, if regions like Europe and Latin America where wheat and corn thrive increase their production and export food to regions under heavy pressure from the warming of the Earth, food shortages can be reduced.

Global Hunger by 2050

The State of Food and Nutrition Security in the World 2020 reports that globally almost 690 million people were at risk of hunger in 2019. Many factors determine how global hunger will develop in the future, including population growth and economic development, as demonstrated in a study in Environmental Research Letters. Our article uses the “middle-of-the-road” socioeconomic pathway where population reaches 9.2 billion, income grows according to historical trends, and the number of undernourished people decreases to 122 million by 2050. Within this socioeconomic setting, we investigate the impact of different climate change scenarios and trade policies on global hunger by 2050.

The worst-case climate scenario of a 4°C warming leads to an extra 55 million people enduring hunger – a 45% increase compared to the situation without climate change. In a protectionist trade environment where vulnerable regions cannot increase their food imports as a response to climate impacts, this effect rises to 73 million. The largest hunger risks are located in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, with respectively a 33 million and 15 million increase in people at risk of hunger in the worst-case climate scenario.

Where barriers to trade are eliminated, “only” 20 million people endure food shortages due to climate change. While this number is high, it is a vast improvement on the 73 million people that would potentially be exposed to hunger without the suggested measures. In the milder climate change scenarios, an intensive liberalization of trade may prevent even more people from enduring hunger owing to global warming. Yet a liberalization of international trade may also involve potential dangers. If Asian countries increase rice exports without making more imports of other products possible, they could well end up with a food shortage within their own borders.

Mobilizing Investment

Our study shows not only that the challenge of ending global hunger is strongly determined by the extent of progress on SDG 13 (climate action), but also that achievement of SDG 2 (zero hunger) is affected by developments articulated in SDG 9 (resilient infrastructure). We find that international trade can relieve regional food shortages and reduce hunger, particularly where trade barriers are eliminated. Such trade integration requires phasing out import tariffs as well as the facilitation of trade through investment in transport infrastructure and technology. Especially in low-income regions such as sub-Saharan Africa infrastructure is weak. In its 2018 African Economic Outlook, the African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates that between USD 130 billion and 170 billion a year is needed to bridge the infrastructure gap in the region by 2025. Given that infrastructure finance averaged only USD 75 billion in recent years, and the largest contribution is coming from budget-constrained national governments, alternative financing through institutional and private investments could be crucial in the face of climate change.

Crisis and Protectionism

In times of crisis, countries are inclined to adopt a protectionist stance. For example, in the face of the current COVID-19 pandemic, several countries have temporarily closed their borders for the export of important food crops (see IFPRI Food Trade Policy Tracker for updated information). Some commentators warn that such measures can have large detrimental effects on food security. Our study finds that also in the context of climate change, a well-thought-out liberalization of trade is needed in order to be able to relieve food shortages properly.

Reference

Janssens C, Havlík P, Krisztin T, Baker J, Frank S, Hasegawa T, Leclère D, Ohrel S, et al. (2020). Global hunger and climate change adaptation through international trade.

Nature Climate Change [

pure.iiasa.ac.at/16575]

This blog post first appeared on the SDG Knowledge Hub website. Read the original post here.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 26, 2020 | Alumni, Climate Change, History, USA, Young Scientists

By Marcus Thomson, IIASA alumnus and a researcher at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), the University of California, Santa Barbara

IIASA alumnus Marcus Thomson explains how what we have learnt about prehistoric farming cultures can be used to provide useful insights on human societal responses to climate change.

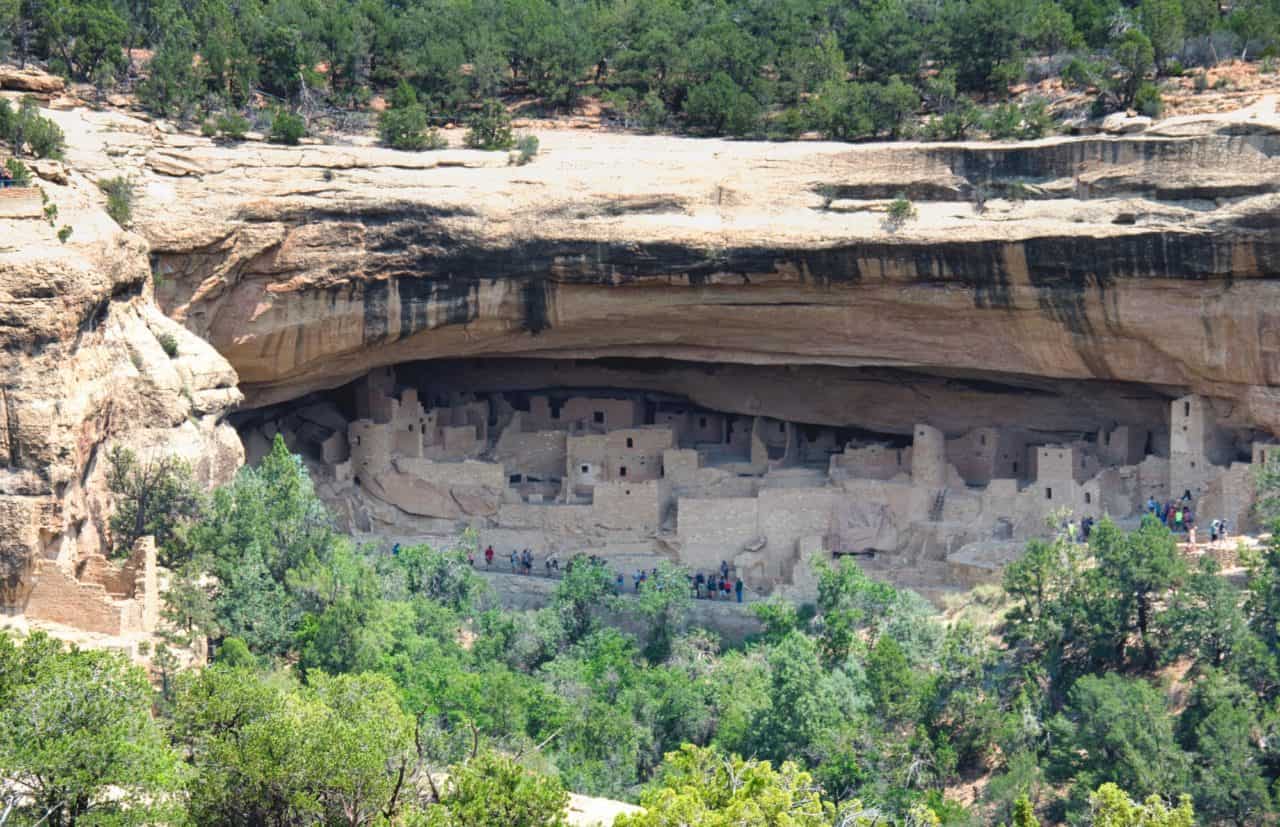

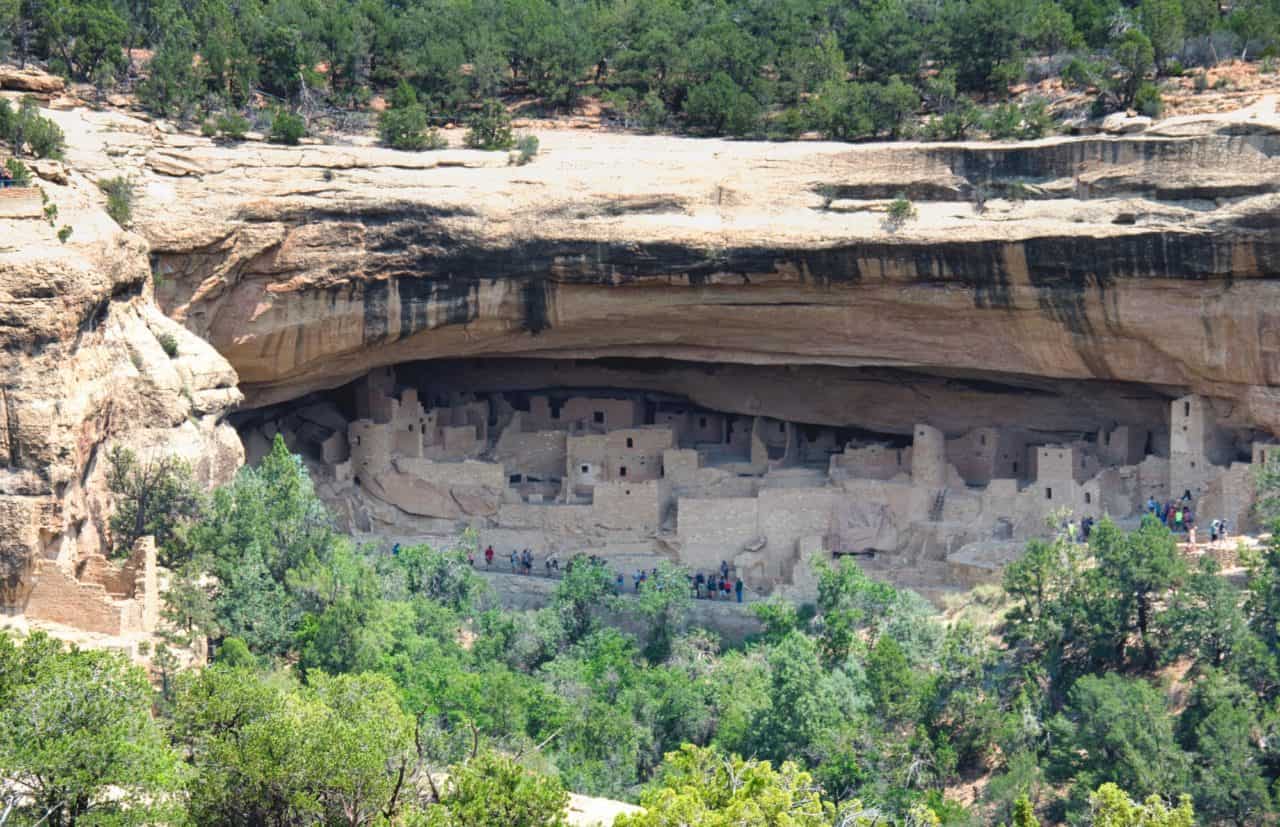

The climate of the western half of the North American continent, between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific coastal region, is dry by European standards. The American Southwest, in particular, centered roughly on the intersection of the states of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, is predominantly desert between high mountain plateaus. It is, and has always been, a challenging environment for farmers. Yet the prehistoric Southwest was home to complex maize-based agricultural societies. In fact, until the 19th century growth of industrial cities like New York, the Southwest contained ruins of the largest buildings north of Mexico — and these had been abandoned centuries before the Spanish arrived in the Americas.

© Mudwalker | Dreamstime.com

For more than a century, researchers have pored over data, from proxies of paleo-environmental change, to historiographies collected by explorers, to archaeology and computational models of human occupation, and produced a detailed picture of the socio-environmental, economic, and climatic conditions that could explain why these sites were abandoned. While details vary in fine-grained analyses of the various sub-groupings of peoples in the region, the big picture is one of societal transformation in adapting to climate change.

Also important is just how the climate changed during the period, because similar dynamics are expected to emerge in the future as a consequence of global warming. European historians point to a medieval era with generally warmer mean annual temperatures. In the Southwestern United States however, which is more sensitive to changes in drought than temperature, the period between roughly AD 850 to 1350 is known as the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA). The warm, dry MCA was followed by a long stretch of increased changes in the availability of water, known as the Little Ice Age (LIA). More frequent “warm droughts” at the end of the MCA, and generally increasing changes in water resources at the onset of the LIA, is thought to be a good analogy for future conditions in western North America.

When I had the good fortune to visit IIASA as a participant of the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) in 2016, I worked with research scholars Juraj Balkovič and Tamás Krisztin to develop a model of ancient Fremont Native American maize. The Fremont were an ancient forager-farmer people who lived in the vicinity of modern Utah. We used a climate model reconstruction of the temperature and rainfall between AD 850 and 1450 to drive this maize crop model, and compared modeled crop yields against changes in radiocarbon-derived occupations – in other words, the information gathered from carbon dated artifacts that show that an area was occupied by a particular people – from a few archaeological areas in Utah.

© Galyna Andrushko | Dreamstime.com

Among our findings was that changes in local temperatures appeared to play a larger role in the lives, practices and habits of the people who lived there than changes in regional, long-term temperature conditions [1]. Later, while a researcher at IIASA myself, I returned to the subject with one of our coauthors, professor Glen MacDonald of the University of California, Los Angeles, using an expanded geographic range and a more sophisticated treatment of radiocarbon dated occupation likelihoods.

We used the climate model to reconstruct prehistoric maize growing season lengths and mean annual rainfall for Fremont sites. We found that the most populous and resilient Fremont communities were at sites with low-variability season lengths; and low populations coincided with, or followed, periods of variable season lengths. This study confirmed the important dependence on climate variability; and more importantly, our results are in line with others on modern smallholder farming contexts.

More details on our latest study [2] have just been published online in Environmental Research Letters (ERL). It will become part of an ERL special issue looking at societal resilience drawing lessons from the past 5000 years. Studies like these can give useful insights on human societal responses to climate change because these ancient civilizations are, in a sense, completed experiments with complex human-environmental systems. For decision makers, who must plan early to commit resources to offset the effects of future climate change on smallholder farmers in similarly drought-sensitive, marginally productive environments, these studies indicate that year-to-year climatic variability drives occupation change more than long-term temperature change.

References:

[1] Thomson MJ, Balkovič J, Krisztin T, & MacDonald GM (2019). Simulated impact of paleoclimate change on Fremont Native American maize farming in Utah, 850–1449 CE, using crop and climate models. Quaternary International, 507, pp.95-107 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15472]

[2] Thomson MJ, & MacDonald GM (In press). Climate and growing season variability impacted the intensity and distribution of Fremont maize farmers during and after the Medieval Climate Anomaly based on a statistically downscaled climate model. Environmental Research Letters.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 19, 2020 | Climate Change, COVID19, USA, Wellbeing, Young Scientists

By Lisa Thalheimer, 2020 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant in the Risk and Resilience and World Population Programs

Lisa Thalheimer shares her journey in researching climate-related migration in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and the importance of taking mental health issues into account in climate science and the policy realm.

© Raul Mellado Ortiz | Dreamstime.com

COVID-19 has changed our idea of normal. These unprecedented, stressful times affect us all – some of us more than others. Fear and anxiety over a new disease without any promise of a vaccine anytime soon, global economic downturn, along with feelings of loneliness and emotional exhaustion due to the lockdown, can leave us mentally exhausted. Rates of depression and addiction-related suicide are in fact already on the rise among young people like myself.

Now imagine you are advised to stay at home, but you cannot do so because climate change has turned your entire life upside down: your house is no longer there, you have lost your job, your family or friends – you are likely to feel unhinged. This is a reality for many migrants across the globe. It is inevitable that existing migration patterns will be shifted beyond disasters alone. Cascading impacts form the still unfolding pandemic could compound. No matter if you are a migrant yourself or not, agency and the choice over the decision whether to leave your house or not, and the luxury to socially distance could potentially not be an option with a systemic shock like COVID-19.

These changes in circumstances have also affected me as a young scientist. I would have been in Laxenburg, getting to know my YSSP peers and IIASA colleagues, but this year’s journey has been rewritten – courtesy of the COVID-19 pandemic.

I was living in Oxford in the UK when I came to realise that mental health is a game changer in the way I manage my day, make decisions, my ability to care for my partner who suffers from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), and making progress on my PhD thesis. Everything felt more difficult. I was overwhelmed. I wanted to understand why this is the case. My interest soon evolved into researching the links between mental health and my PhD topic of climate-related migration.

For the article “The hidden burden of pandemics, climate change and migration on mental health”, I teamed up with an epidemiologist who specialises in mental health at my old university home, the Earth Institute in New York City. This research experience was an eye-opener, both personally and scientifically.

In our article, we focused on the US, as it has been hit hardest by COVID-19 – in mid-August, the number of COVID-19 cases exceeded five million. On top of this, depression and anxiety are already prominent among Americans, as is costly impacts from disasters. Hurricanes cost the US around US$ 17 billion every year, but estimates show a higher probability of extremely damaging hurricane seasons with climate change. We may know the impact of climate change on assets and on physical health, but what about mental health impacts?

© Raggedstonedesign | Dreamstime.com

Although my coauthor and I come from different scientific disciplines, I soon came to realize that our scientific approach has a common denominator: systems thinking. Accounting for interconnections and cascading effects, our article shed light on different systems affected by COVID-19 and situations where mental health issues are likely to become increasingly prevalent in a changing climate. The article focuses on already vulnerable parts of the population, for example those who have been impacted by Hurricane Katrina or Hurricane Harvey – the latter of which has been made worse by climate change. The article illustrates how COVID-19 becomes a risk multiplier for climate migrants in three distinct case studies: key workers in New York as urban setting, seasonal migration dynamics, and disproportionate effects on black and Latino communities. Unrelenting effects include loss of employment, and a lower likelihood of being able to work from home or to have health insurance than white people.

A better understanding of the mental health-migration-climate change nexus can help absorb adverse mental health outcomes from COVID-19, which would otherwise compound. We however need to tackle systemic risks affecting mental health through synergies in research and policy, and an integrated intervention approach. Free mental health support for key workers through tele-therapy and mental health hotlines provide a practical way forward. Personally, I learned that climate migrants have been relentlessly resilient to systemic shocks. Nevertheless, with mental health issues, it becomes increasingly hard to maintain such resilience. With this commentary, I hope that mental health and interdisciplinary research finds its way in climate science and in the policy realm. We all need a clear mind to attain the Sustainable Development Goals.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 5, 2020 | Alumni, Climate Change, Science and Policy, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Leila Niamir, post-doctoral researcher at the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), Germany and IIASA YSSP alumna.

© Cienpies Design Illustrations | Dreamstime

Weather patterns and events are changing and becoming more extreme, sea levels are rising, and greenhouse gas emissions are now at their highest levels in history[1]. Climate change is affecting every individual in every city on every continent. It imposes adverse impact on people, communities, and countries, disrupting regional and national economies.

Climate change mitigation refers to efforts to reduce or prevent emissions of greenhouse gases to limit the magnitude of long-term climate change. Human consumption, in combination with a growing population, contributes to climate change by increasing the rate of greenhouse gas emissions. Over the last decade, instigated by the Paris Agreement, the efforts to limit global warming have been expanding. Significant attention is being devoted to new energy technologies on both the production and consumption sides, however, changes in individual behavior and management practices as part of the mitigation strategy are often neglected[2]. This might derive from the complex nature of human which makes explaining and affecting human behavior a difficult task. As a result, quantitative tools to assess household emissions, considering the diversity of behaviors and a variety of psychological and social factors influencing them beyond purely economic considerations, are scarce. Policymakers would benefit from reliable decision supporting tools that explore the interaction of economic decision-making and behavioral heterogeneity in households behavioral and lifestyle changes, when testing climate mitigation policies (e.g. carbon pricing, subsidies)[3].

To address this issue, during my PhD research I studied the potential of behavioral changes among heterogeneous households regarding energy use and their role in mitigating climate change. By designing and conducting comprehensive household surveys, it was explored how individuals choose to change their energy behaviour and what factors trigger or inhibit these choices[4]. Decision support tools are designed to study large-scale regional effects of individual actions, and to explore how they may change over time and space. The model explicitly treats behavioral triggers and barriers at the individual level, assuming that energy use decision making is a multi-stage process. This theoretically and empirically grounded simulation model offers policymakers ways to explore various policy portfolios by running diverse micro and macro scenarios.

This model was further developed during my collaboration with the IIASA the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), to estimate macro impacts of individuals’ energy behavioral changes on carbon emissions[5]. Within this research, we illustrate that individual energy behavior, especially when amplified through social context, shapes energy demand and, consequently, carbon emissions. Our results show that residential energy demand is strongly linked to personal and social norms. When assessing the cumulative impacts of these behavioral processes, we quantify individual and combined effects of social dynamics and of carbon pricing on individual energy efficiency and on the aggregated regional energy demand and emissions.

In summary, mitigating climate change requires massive worldwide efforts and strong involvement of regions, cities, businesses and individuals, in addition to the commitments at the national levels. We should always keep in mind that every single behavior matters. In the transition to a sustainable and resilient society, we –as individuals- are more than just consumers.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

[1] Climate Action– United Nations Sustainable Development Goals https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change/

[2] Creutzig, F., et al. (2018). Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nature Climate Change 8, 268-271; Grubler, A., et al. (2018). A low energy demand scenario for meeting the 1.5 degrees C target and sustainable development goals without negative emission technologies. Nature Energy 3, 515-527; Creutzig, F., et al. (2016). Beyond Technology: Demand-Side Solutions for Climate Change Mitigation. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, Vol 41 41, 173-198

[3] Niamir, L. (2019). Behavioural Climate Change Mitigation: from individual energy choices to demand-side potential (University of Twente); Creutzig, F., et al. (2018). Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nature Climate Change 8, 268-271; Niamir, L., et al. (2018). Transition to low-carbon economy: Assessing cumulative impacts of individual behavioural changes. Energy Policy, 118; Stern N. Economics: Current climate models are grossly misleading. Nature 530(7591):407–9.

[4] Niamir, L. et al. (2020). Demand-side solutions for climate mitigation: Bottom-up drivers of household energy behaviour change in the Netherlands and Spain. Energy Research & Social Science, 62, 101356.

[5] The results of this collaboration was presented at Impacts World 2017 and won the best prize, and also published at Climatic Change Journal.

Jan 17, 2020 | Climate Change, Demography

By Roman Hoffmann, Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW, and University of Vienna), Vienna Institute of Demography, Austrian Academy of Sciences, and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

Taking action to combat climate change and its impacts is urgent and vital to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Although per capita emissions are still highest in high-income countries, several emerging low and middle-income countries have seen a rise in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions in recent years. While much of that rise was due to increased (export-oriented) industrial activities, changing lifestyle, consumption, and mobility patterns also played a significant role. How people can be encouraged to behave in an environmentally friendly way is a fundamental question for climate change mitigation. Despite a call for a stronger emphasis on demand-side solutions in mitigation strategies, little is known about the determinants of pro-environmental behaviors of people from the developing world.

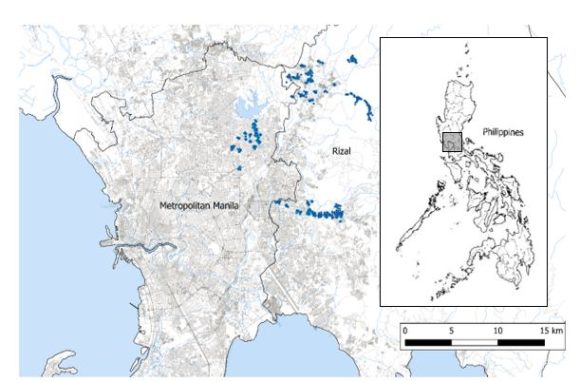

© Roman Hoffman | IIASA

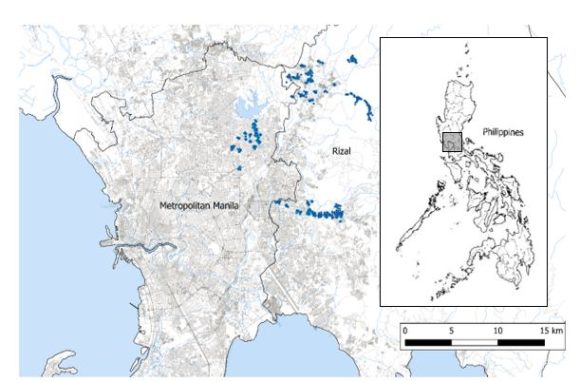

In a study with IIASA researcher Raya Muttarak, which has recently been published in Environmental Research Letters, we found that education significantly contributes to increasing pro-environmental orientations and actions among low-income households in the Philippines. As an emerging lower-middle-income country, the Philippines are faced with severe environmental issues, such as pollution, deforestation, and environmental degradation. Already in the 1990s, public policy has responded to these challenges by developing several environmentally-focused learning initiatives and by making environmental education a fundamental pillar of the national school curriculum. Today, according to the World Value Survey, more than 73% of the population can identify with a person who gives importance to looking after the environment compared to 55% and 63% in the neighboring countries Thailand and Malaysia, respectively.

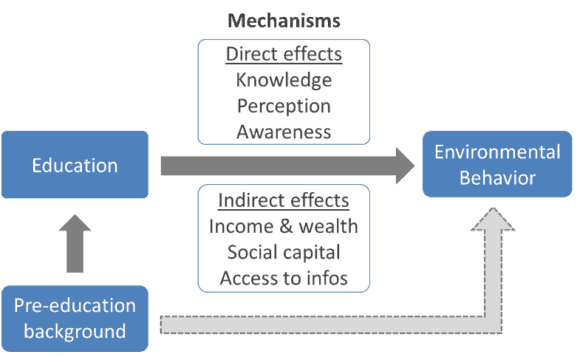

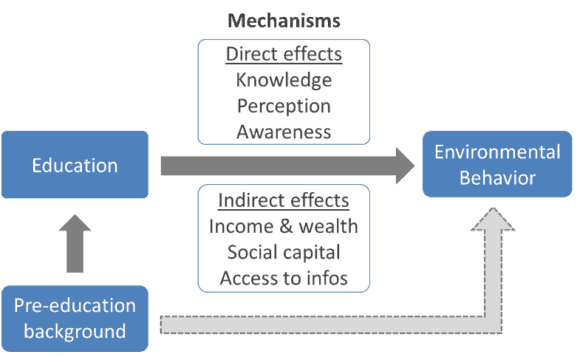

Figure 1 – Conceptual framework explaining the direct and indirect channels through which education influences environmental behavior. Note: The empirical design controls for the respondents’ pre-education background and indirect channels of influence allowing us to capture the direct effects of education on pro-environmental behaviors.

Based on original cross-sectional survey data, we found education to be positively related to pro-environmental behaviors such as recycling, proper garbage disposal, and planting trees. An additional year of schooling is estimated to increase the probability of carrying out climate-friendly actions by a substantial 3.3%. Going beyond previous research, we explored some of the underlying mechanisms through which education influences environmental behavior. . While knowledge and awareness raising are both important, it is found that education influences behavior mainly by increasing awareness about the anthropogenic causes of climate change, which may consequently affect the individual perception of self-efficacy in reducing human impacts on the environment. This is in line with the environmental psychology literature, which finds that poor understanding of the connection between human actions and climate change influences the perception of one’s ability to control and take action against it. People will become active only if the perceived likelihood of achieving a desired outcome is high enough. Education can hence play a vital role in promoting a better understanding of climate change and in raising awareness about the impacts of human activities.

Figure 2 – Map of study areas with locations of respondents’ homes. The study areas encompassed both more urban and rural areas located in Rizal province towards the East of the National Capital Region

In line with recent efforts of the international community to promote education for sustainable development, our study provides solid empirical evidence confirming the important role of education in climate change mitigation efforts. Investments in education can make an important contribution in raising awareness and ultimately in promoting green behavior helping to reduce the human impacts on the global climate system. In this regard, while it is important to provide learners with the necessary tools and capabilities to undertake pro-environmental actions, it is also key to raise their perceived self-efficacy. Education should thus not only focus on the transfer of knowledge and information, but also highlight the importance of the individual contribution in mitigating the harmful consequences of global environmental change.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.