Nov 20, 2020 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

By Greg Davies-Jones, 2020 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Greg Davies-Jones sits down with 2020 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant Lisa Thalheimer to discuss how attribution science can play a leading role in addressing disaster displacement.

We live in the era of the greatest human movement in recorded history – there are more people on the move today than at any other point in our past. Despite the common misconception that most migrants cross borders, a lot of migration actually occurs internally. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, a staggering 72% of internal migration is linked to displacement due to natural hazards or extreme weather.

Pinpointing the finer details of how human mobility might evolve remains a complex undertaking. Contemporary migratory movements reflect the complex patterns of social and economic globalization – they flow in all directions and affect all countries in one way or another. It is clear that given the rising global average temperatures, natural hazards and extreme weather events will increase in frequency, intensity, and duration, adversely effecting many parts of the globe. A better understanding of how human-induced climate change influences disaster displacement will undoubtedly be essential in addressing future human mobility and informing the debate on climate and migration policies.

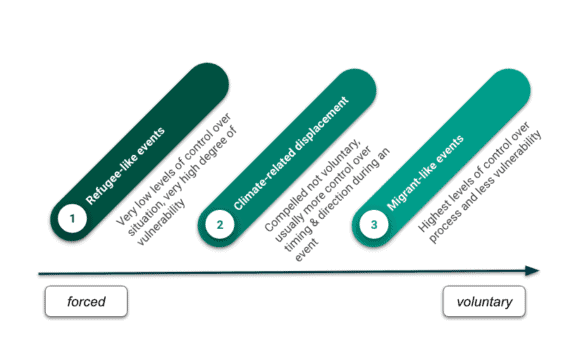

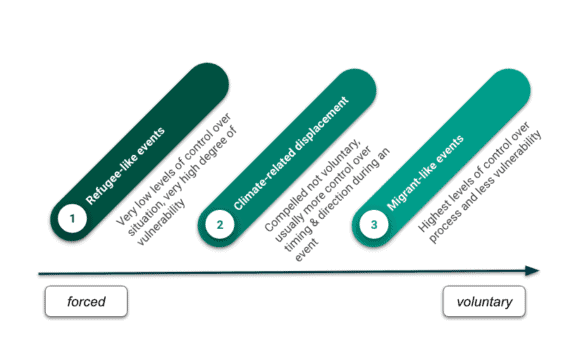

Figure: Climate-related displacement on an axis of forced to voluntary human mobility. Thalheimer (2020)

The focus of 2020 YSSP participant Lisa Thalheimer’s research is on internal displacement in East Africa, in particular, Somalia. As part of her YSSP project, Thalheimer hopes to determine whether, and to what extent, human-induced climate change altered the likelihood of extreme weather-related displacement in Somalia by conflating econometric methods and Probabilistic Event Attribution (PEA).

“Econometrics is essentially the application of statistical methods to quantify impacts and PEA is a way of examining to what extent extreme weather events can be linked with past man-made emissions. By combining the two methods we hope to quantify the ramifications of extreme weather and displacement in East Africa,” she explains.

This is no mean feat, as PEA itself is a relatively new science and many challenges still exist in the field of event attribution ̶ a field of research concerned with the process by which the causes of behavior and events can be explained. In this instance, the idea was to study each extreme weather event individually to determine if human-induced climate change may have added to the intensity or likelihood of the event occurring. PEA is a growing science within this field and relies on the availability of long-term meteorological observations and the reliability of climate model simulations. In terms of migration and the accompanying econometric methods, the complexity of this work is mainly in data capturing.

“The difficulty with migration data capturing is at the start – before you can capture anything, you must ascertain how the data is defined, as different countries define mobility in different ways. For instance, it could be time – where did you live one year ago as opposed to five years ago? That’s the first complexity. Then you must work out who collects data on who – in Europe, we have fundamental freedom of movement within the EU, so unless you file for residency, your movement is not recorded. Another complexity is because we want to see if climate change is part of the driver ̶ directly or indirectly. We need to know not just where people are now, but where they have been and where they came from, so we can match the climate with their movements. All of this highlights how difficult it is to carry out this type of analysis,” Thalheimer adds.

In Somalia, the team relied on previously collected forced migration data, for example, from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). These UNHCR datasets collected in Somalia were comprehensive and included not only origin and destination information but also a categorization of the primary reason for the displacement.

© Aleksandr Frolov | Dreamstime.com

The investigation homed in on one extreme weather case study in the region: The April 2020 heavy rainfall in Southern Ethiopia, which led to several severe flooding events in South Somalia. In this particular case, however, no appreciable connection could be made between human-induced climate change and the resultant displacement. Despite this somewhat chastening outcome, the achievement of this study is not proving a definitive attributable link between human-induced climate change and the April 2020 rainfall, but rather the construction of the adjustable attribution framework presented that can be applied directly to other events and displacement contexts.

As previously mentioned, there are, however, limitations to this novel methodology, especially in regions like Somalia that lack exhaustive observational weather and displacement data. According to Thalheimer, exploring ways of effectively applying this framework in countries vulnerable to climate change will be particularly important going forward.

“Event attribution studies do not usually form the basis of climate migration analysis, disaster risk reduction, or adaptation strategies. Yet, to respond appropriately to these impacts and affected populations, we must develop a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the nature of these impacts, as well as knowledge on how these might evolve over time. Event attribution is a tool we can employ to do this,” she concludes.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 12, 2019 | Austria, Communication, Demography, Women in Science

By Nadejda Komendantova, researcher in the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program

Nadejda Komendantova discusses how misinformation propagated by different communication mediums influence attitudes towards migrants in Austria and how the EU Horizon 2020 Co-Inform project is fostering critical thinking skills for a better-informed society.

© Skypixel | Dreamstime.com

Austria has been a country of immigration for decades, with the annual balance of immigration and emigration regularly showing a positive net migration rate. A significant share of the Austrian population are migrants (16%) or people with an immigrant background (23%). The migration crisis of 2015 saw Austria as the fourth largest receiver of asylum seekers in the EU, while in previous years, asylum seekers accounted for 19% of all migrants. Vienna has the highest share of migrants of all regions and cities in Austria, and over 96% of Viennese have contact with migrants in everyday life.

Scientific research shows that it is however not primarily these everyday situations that are influencing attitudes towards migrants, but rather the opinions and perceptions about them that have developed over the years. Perceptions towards migration are frequently based on a subjectively perceived collision of interests, and are socially constructed and influenced by factors such as socialization, awareness, and experience. Perceptions also define what is seen as improper behavior and are influenced by preconceived impressions of migrants. These preconceptions can be a result of information flow or of personal experience. If not addressed, these preconditions can form prejudices in the absence of further information.

The media plays an essential role in the formulation of these opinions and further research is necessary to evaluate the impact of emerging media such as social media and the internet, and their consequent impact on conflicting situations in the limited profit housing sector. Multifamily housing in particular, is getting more and more heterogeneous and the impacts of social media on perceptions of migrants are therefore strongest in this sector, where people with different backgrounds, values, needs, origins and traditions are living together and interacting on a daily basis. Perceptions of foreign characteristics are also frequently determined by general sentiments in the media, where misinformation plays a role. Misinformation has been around for a long time, but nowadays new technologies and social media facilitate its spread, thus increasing the potential for social conflicts.

Early in 2019, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) organized a workshop at the premises of the Ministry of Economy and Digitalization of the Austrian Republic as part of the EU Horizon 2020 *Co-Inform project. The focus of the event was to discuss the impact of misinformation on perceptions of migrants in the Austrian multifamily limited profit housing sector.

Nadejda Komendantova addressing stakeholders at the workshop.

We selected this topic for three reasons: First, this sector is a key pillar of the Austrian policy on socioeconomic development and political stability; and secondly, the sector constitutes 24% of the total housing stock and more than 30% of total new construction. In the third place, the sector caters for a high share of migrants. For example, in 2015 the leading Austrian limited profit housing company, Sozialbau, reported that the share of their residents with a migration background (foreign nationals or Austrian citizens born abroad) had reached 38%.

Several stakeholders, including housing sector policymakers, journalists, fact checkers, and citizens participated in the workshop. Among them were representatives from the Austrian Chamber of Labor, Austrian Limited Profit Housing (ALPH) companies “Neues Leben”, “Siedlungsgenossenschaft Neunkirchen”, “Heim”, “Wohnbauvereinigung für Privatangestellte”, the housing service of the municipality of Vienna, as well as the Austrian Association of Cities and Towns.

The workshop employed innovative methods to engage stakeholders in dialogue, including games based on word associations, participatory landscape mapping, as well as wish-lists for policymakers and interactive, online “fake news” games. In addition, the sessions included co-creation activities and the collection of stakeholders’ perceptions about misinformation, everyday practices to deal with misinformation, co-creation activities around challenges connected with misinformation, discussions about the needs to deal with misinformation, and possible solutions.

During discussions with workshop participants, we identified three major challenges connected with the spread of misinformation. These are the time and speed of reaction required; the type of misinformation and whether it affects someone personally or professionally; excitement about the news in terms of the low level of people’s willingness to read, as well as the difficulties around correcting information once it has been published. Many participants believed that they could control the spread of misinformation, especially if it concerns their professional area and spreads within their networking circles or among employees of their own organizations. Several participants suggested making use of statistical or other corrective measures such as artificial intelligence tools or fact checking software.

The major challenge is however to recognize misinformation and its source as quickly as possible. This requirement was perceived by many as a barrier to corrective measures, as participants mentioned that someone often has to be an expert to correct misinformation in many areas. Another challenge is that the more exciting the misinformation issue is, the faster it spreads. Making corrections might also be difficult as people might prefer emotional reach information to fact reach information, or pictures instead of text.

The expectations of policymakers, journalists, fact checkers, and citizens regarding the tools needed to deal with misinformation were different. The expectations of the policymakers were mainly connected with the creation of a reliable, trusted environment through the development and enforcement of regulations, stimulating a culture of critical thinking, and strengthening the capacities of statistical offices, in addition to making relevant statistical information available and understandable to everybody. Journalists and fact checkers’ expectations on the other hand, were mainly concerned with the development and availability of tools for the verification of information. The expectations of citizens were mainly connected with the role of decision makers, who they felt should provide them with credible sources of information on official websites and organize information campaigns among inhabitants about the challenges of misinformation and how to deal with it.

*Co-Inform is an EU Horizon 2020 project that aims to create tools for better-informed societies. The stakeholders will be co-creating these tools by participating in a series of workshops in Greece, Austria, and Sweden over the course of the next two years.

Adapted from a blog post originally published on the Co-Inform website.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 17, 2019 | Alumni, IIASA Network

Monika Bauer, IIASA Network and Alumni Officer, interviewed alumnus Dennis Meadows during his recent visit to IIASA.

Dennis Meadows with colleagues in the IIASA Water & RISK Programs © Monika Bauer | IIASA

“It’s a great pleasure to be back at IIASA because the institute really had a big impact on my professional life,” said Dennis Meadows, coauthor of the seminal book Limits to Growth, after his lecture to IIASA staff during a recent visit to the institute. “I came to IIASA, and it gave me so many new ideas and contacts. It became the fuel for my professional activities for a long time.”

Meadows visited the IIASA Energy Program in 1977 when Roger Levien was director, and he says that Levien greatly impacted the way he viewed problems. In his lecture titled, Lessons from 50 years of model-based policy advocacy, he pointed out that Levien looked at problems as universal or global, and that he uses the criteria Levien passed on to him in what he calls “problem selection” to this day. Meadows also spent some time at the institute from 1983-1984 when C.S. Buzz Holling was director.

During his lecture, Meadows highlighted the idea of using the concept of an “invisible college” as a strategy to implement academic work. He explained that an “invisible college” usually constitutes a group of about 50 people connected with an issue, who, while they do not necessarily all have to agree on the issue or do the same work, can collectively come up with a solution.

© Dennis Meadows

Meadows created his version of an invisible college through the Balaton Group, a global network for collaboration on systems and sustainability that he founded in 1982. He says that the network is meant to “connect and empower people who will go back home and do good things”. Meadows stopped by IIASA on his way to the group’s annual retreat in at Lake Belaton in Hungary, where 50 leading scientists, teachers, consultants, writers, and managers annually get together to discuss topical issues on their own costs. According to Meadows, this in itself shows the value individuals see in the meetings. The results of past meetings are outlined on the group’s webpage.

When asked about his key messages for IIASA, Meadows’ answers focused on the institute’s alumni network and exploring a deeper understanding of resilience.

“The incredible power of IIASA lies in its alumni, rather than in its models. You create the alumni network through the process of creating models. IIASA doesn’t have many models, but it has thousands of alumni. One of the first things I would look at is how to link alumni more strongly together, so they could help each other. I still have affection for the institute and respect for what it does, and I’m sure that my opinion is shared by many.”

His second take-away for IIASA concerns building a deeper expertise on resilience. “Sustainable development is something that is hard to realize, while there is no doubt that shocks will continue to occur, and there is no unified theory in resilience yet. In my opinion, IIASA has an opportunity to tap into a huge legacy of understanding that goes back to Buzz Holling’s work.”

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 17, 2019 | Alumni, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

By Tobias Sieg, IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program alumnus

IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program alumnus Tobias Sieg explains how risk assessments considering uncertainties can substantially contribute to better risk management and consequently to the prevention of economic impacts.

© Topdeq | Dreamstime.com

According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Landscape 2018, extreme weather events and natural disasters are ranked among the top three global risks. For many regions, hydro-meteorological risks – in other words, weather or water related events like cyclones or floods that pose a threat to populations or the environment – constitute the biggest threat. This calls for a comprehensive scientific risk assessment with a particular focus on large associated uncertainties.

Assessing the risk of hydro-meteorological hazards without considering these uncertainties, is like entering a pitch-dark labyrinth. You have no idea where you are and where you will end up. If you enter with a flashlight, you might still not immediately know exactly where you will end up, but at least you can assess your possibilities for finding a way out.

We should all care to see those possibilities and to identify uncertainties, since the consequences of hydro-meteorological hazards can have severe impacts on socioeconomic systems, and global- and climate change could favor the occurrence of floods. An increase in extreme weather events, such as heavy precipitation can be expected along with an increasingly warmer climate. In combination with uncontrolled socioeconomic development, these extreme weather events could potentially trigger more intense hazardous flood events in the future. Appropriate management of their consequences is therefore required, starting from today, while pro-actively thinking about the future. To that end, risk management policy and practice need reliable estimates of direct and indirect economic impacts.

The reliability of existing estimates is usually quite low and, what is maybe even worse, they are not communicated properly. This may signal a false sense of certainty regarding the prediction of future climate-related risks.

In two recent studies, my co-authors and I developed and applied a novel method, which specifically focuses on the communication of the reliability of economic impact estimates and the associated uncertainties. The proposed representation of uncertainties enables us to shed some light on the possibilities of how a specific event can affect economic systems. As a Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant with the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program, I applied the method together with my supervisors Thomas Schinko and Reinhard Mechler, to estimate the overall economic impacts of a major flood event in Germany in 2013.

The estimated overall economic impacts comprise both direct and indirect impacts. Direct impacts are usually caused by physical contact of the floodwater with buildings, while indirect impacts can also occur in regions that are not directly affected by a flood. For example, obstructions of the infrastructure can lead to delayed deliveries, in turn leading to negative impacts for the production of goods outside the flooded areas. The crucial novelty of this method is the integrated assessment of direct and indirect economic impacts. In particular, by considering how the uncertainties associated with the estimation of direct economic impacts propagate further into the estimates of indirect economic impacts.

Being able to reproduce what has happened in the past is essential to making credible predictions about what could potentially happen in the future. A comparison of reported direct economic impacts and model-based estimates reveals that the estimation technique already works quite reliably. The good news is that anyone can help to increase the predictive reliability even further. The method uses the crowdsourced OpenStreetMap dataset to identify affected buildings. The more detailed the given information about a building is, the more reliable the impact estimations can get.

Our study reveals that the potential of short-term indirect economic impacts (without considering recovery) are quite high. In fact, our results show that the indirect impacts can be as high as the direct economic impacts. Yet, this varies a lot for different economic sectors. The manufacturing sector, for instance, is much more affected by indirect economic impacts, since it is heavily dependent on well-functioning supply chains. This information can be used in emergency risk management where decisions have to be made about giving immediate help to companies of a specific sector to reduce high long-term indirect economic impacts.

We are now looking at different possibilities of how flood events could affect the economic system. Having a range of possibilities of the relation between these impacts makes them transferable between different regions with similar economic systems. Our results are therefore also relevant more broadly beyond the German case. This representation of uncertainties can help to get to a more credible and consistent risk assessment across all spatial scales. Thus, the method is able to potentially facilitate the fulfillment of some of the calls of the UN Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction.

Detailed risk assessments considering uncertainties can substantially contribute to better risk management and consequently to the prevention of economic impacts – direct and indirect, both now and in the future.

References:

[1] Sieg T, Schinko T, Vogel K, Mechler R, Merz B & Kreibich H (2019). Integrated assessment of short-term direct and indirect economic flood impacts including uncertainty quantification. PLoS ONE 14(4): e0212932. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15833]

[2] Sieg T, Vogel K, Merz B & Kreibich H (2019). Seamless estimation of hydro-meteorological risk across spatial scales. Earth’s Future. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EF001122

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 10, 2018 | Demography, Education, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

© SasinTipchai | Shutterstock

By Sandra Ortellado, 2018 Science Communication Fellow

Science fiction depicts the future with a combination of fascination and fear. While artificial intelligence (AI) could take us beyond the limits of human error, dystopic scenes of world domination reveal our greatest fear: that humans are no match for machines, especially in the job market. But in the so-called fourth industrial revolution, often known as Industry 4.0, the line between future and fiction is a thread of reality.

Over the next 13 years, impending automation could force as many as 70 million workers in the US to find another way to make money. The role of technology is not only growing but also demanding a completely new way of thinking about the work we do and our impact on society because of it.

Rather than focusing on which jobs will disappear because of technological disruption, we could be identifying the most resilient tasks within jobs, says J. Luke Irwin, 2018 YSSP participant. His research in the IIASA World Population program uses a role- and task-based analysis to investigate professions that will be most resilient to technological disruption, with the hope of guiding workforce development policy and training programs.

“We are getting better and better at programming algorithms for machines to do things that we thought were really only in the realm of humans,” says Irwin. “The amount of disruption that’s going to happen to the work industry in the next ten years is really going to impact everyone.”

However, the fear and instability created by the potential disruption elicit chaos, and the response is hard to organize into constructive action. While the resources remain untapped, creativity and imagination are wasted on speculation instead of preparation.

“I couldn’t stand that there’s all this great evidence-based work out there about how we can improve people’s lives and no one is using it,” said Irwin, “I’m trying to align a lot of research and put it in a place where you can compare it and make it more useful and more transferable between the people who would be talking about this: educators, policymakers, employers, and anybody in the workforce.”

Using a German dataset with vocational training as well as time and task information, Irwin will break down jobs into the specific cognitive and physical skills involved and rank the durability of each skill.

Based on the identified jobs and skills, Irwin will go on to draw connections between labor-force capabilities and education policies. His goal is to scale the findings of the most resilient skills to the German labor system so that policymakers and academic institutions can retrain currently displaced workforces and reimagine the future of human work.

After all, while about half the duties workers currently handle could be automated, Mckinsey Global Institute suggests that less than 5% of occupations could be entirely taken over by computers. The future of predictable, repetitive, and purely quantitative work may be threatened, but automation could also open the door for occupations we can’t even imagine yet.

“I think people are amazing and that they have a lot more potential than we are currently capable of fulfilling,” says Irwin.

The World Economic Forum estimates that 65% of children today will end up in careers that don’t even exist yet. For now, an increasingly self-employed millennial generation works insecure, unprotected jobs. The new gig economy, characterized by temporary contracted positions, offers independence but also instability in the labor market.

Without stable work, people lose a sense of security, and that can be dangerous for a policy system that isn’t built to handle uncertainty.

The last industrial revolution caused two or three generations of people to be thrown into poverty and lose everything they had because it was all tied into their job, recalls Irwin.

“Everything gets bad when things are uncertain,” says Irwin, “And this is a very uncertain time. We need to have a better idea of what’s coming so we can actually make some change.”

Irwin, who earned his Master’s in Public Health in 2014, wants his work to have a preventative focus, trying to find those things that not enough people are talking about, but have the potential to make a huge impact on public well-being.

“Especially in the United States, where I live, we’re so tied up with our jobs—it seems like it’s over half our identity,” says Irwin, “We live to work in America.”

In a place like the US, where a job is not only a source of income, but also an identity and a health factor, Irwin’s research offers hope that technological disruption can foster opportunity instead of chaos.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.