By Greg Davies-Jones, 2020 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Greg Davies-Jones sits down with 2020 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant Lisa Thalheimer to discuss how attribution science can play a leading role in addressing disaster displacement.

We live in the era of the greatest human movement in recorded history – there are more people on the move today than at any other point in our past. Despite the common misconception that most migrants cross borders, a lot of migration actually occurs internally. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, a staggering 72% of internal migration is linked to displacement due to natural hazards or extreme weather.

Pinpointing the finer details of how human mobility might evolve remains a complex undertaking. Contemporary migratory movements reflect the complex patterns of social and economic globalization – they flow in all directions and affect all countries in one way or another. It is clear that given the rising global average temperatures, natural hazards and extreme weather events will increase in frequency, intensity, and duration, adversely effecting many parts of the globe. A better understanding of how human-induced climate change influences disaster displacement will undoubtedly be essential in addressing future human mobility and informing the debate on climate and migration policies.

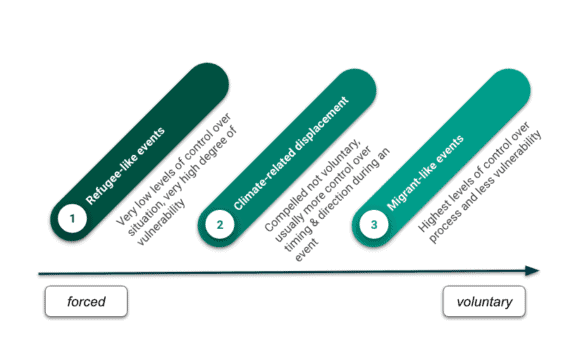

Figure: Climate-related displacement on an axis of forced to voluntary human mobility. Thalheimer (2020)

The focus of 2020 YSSP participant Lisa Thalheimer’s research is on internal displacement in East Africa, in particular, Somalia. As part of her YSSP project, Thalheimer hopes to determine whether, and to what extent, human-induced climate change altered the likelihood of extreme weather-related displacement in Somalia by conflating econometric methods and Probabilistic Event Attribution (PEA).

“Econometrics is essentially the application of statistical methods to quantify impacts and PEA is a way of examining to what extent extreme weather events can be linked with past man-made emissions. By combining the two methods we hope to quantify the ramifications of extreme weather and displacement in East Africa,” she explains.

This is no mean feat, as PEA itself is a relatively new science and many challenges still exist in the field of event attribution ̶ a field of research concerned with the process by which the causes of behavior and events can be explained. In this instance, the idea was to study each extreme weather event individually to determine if human-induced climate change may have added to the intensity or likelihood of the event occurring. PEA is a growing science within this field and relies on the availability of long-term meteorological observations and the reliability of climate model simulations. In terms of migration and the accompanying econometric methods, the complexity of this work is mainly in data capturing.

“The difficulty with migration data capturing is at the start – before you can capture anything, you must ascertain how the data is defined, as different countries define mobility in different ways. For instance, it could be time – where did you live one year ago as opposed to five years ago? That’s the first complexity. Then you must work out who collects data on who – in Europe, we have fundamental freedom of movement within the EU, so unless you file for residency, your movement is not recorded. Another complexity is because we want to see if climate change is part of the driver ̶ directly or indirectly. We need to know not just where people are now, but where they have been and where they came from, so we can match the climate with their movements. All of this highlights how difficult it is to carry out this type of analysis,” Thalheimer adds.

In Somalia, the team relied on previously collected forced migration data, for example, from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). These UNHCR datasets collected in Somalia were comprehensive and included not only origin and destination information but also a categorization of the primary reason for the displacement.

© Aleksandr Frolov | Dreamstime.com

The investigation homed in on one extreme weather case study in the region: The April 2020 heavy rainfall in Southern Ethiopia, which led to several severe flooding events in South Somalia. In this particular case, however, no appreciable connection could be made between human-induced climate change and the resultant displacement. Despite this somewhat chastening outcome, the achievement of this study is not proving a definitive attributable link between human-induced climate change and the April 2020 rainfall, but rather the construction of the adjustable attribution framework presented that can be applied directly to other events and displacement contexts.

As previously mentioned, there are, however, limitations to this novel methodology, especially in regions like Somalia that lack exhaustive observational weather and displacement data. According to Thalheimer, exploring ways of effectively applying this framework in countries vulnerable to climate change will be particularly important going forward.

“Event attribution studies do not usually form the basis of climate migration analysis, disaster risk reduction, or adaptation strategies. Yet, to respond appropriately to these impacts and affected populations, we must develop a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the nature of these impacts, as well as knowledge on how these might evolve over time. Event attribution is a tool we can employ to do this,” she concludes.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.