Aug 26, 2020 | Alumni, Climate Change, History, USA, Young Scientists

By Marcus Thomson, IIASA alumnus and a researcher at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), the University of California, Santa Barbara

IIASA alumnus Marcus Thomson explains how what we have learnt about prehistoric farming cultures can be used to provide useful insights on human societal responses to climate change.

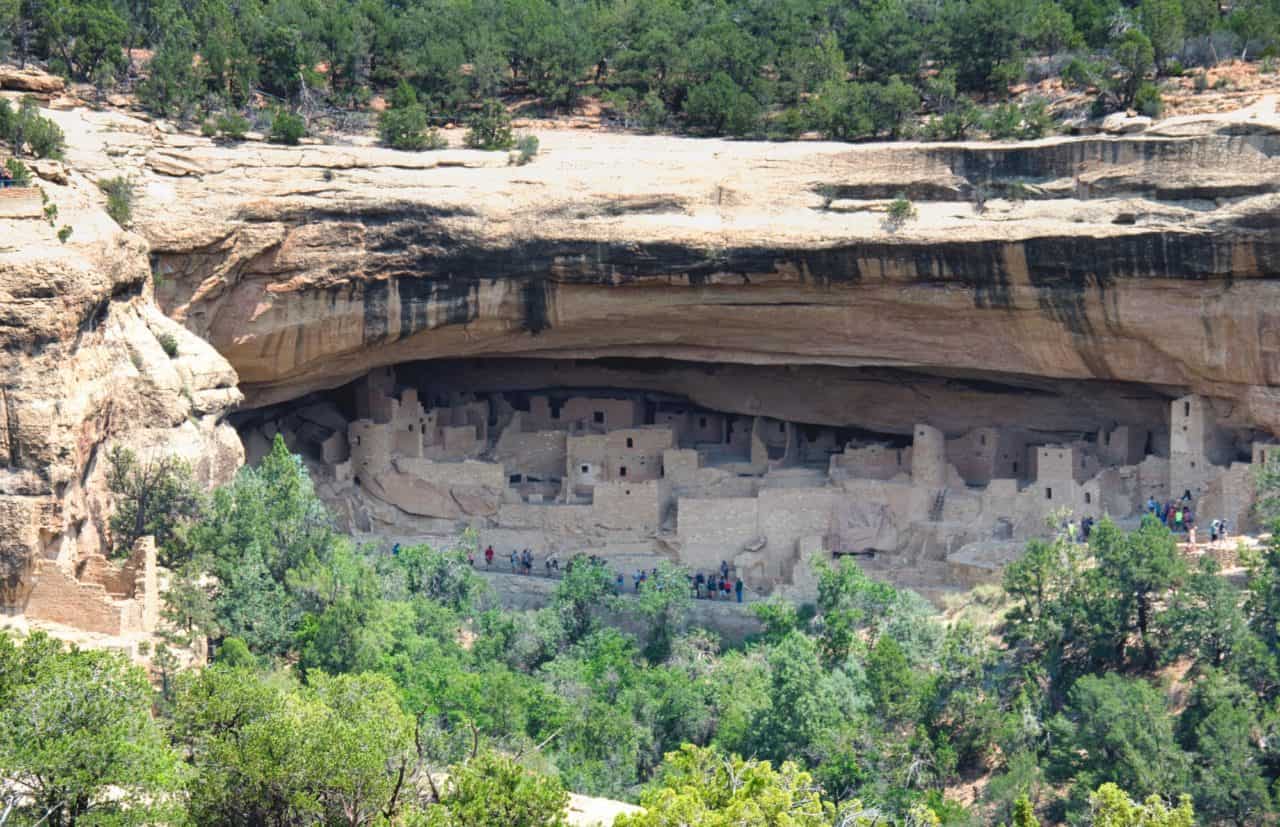

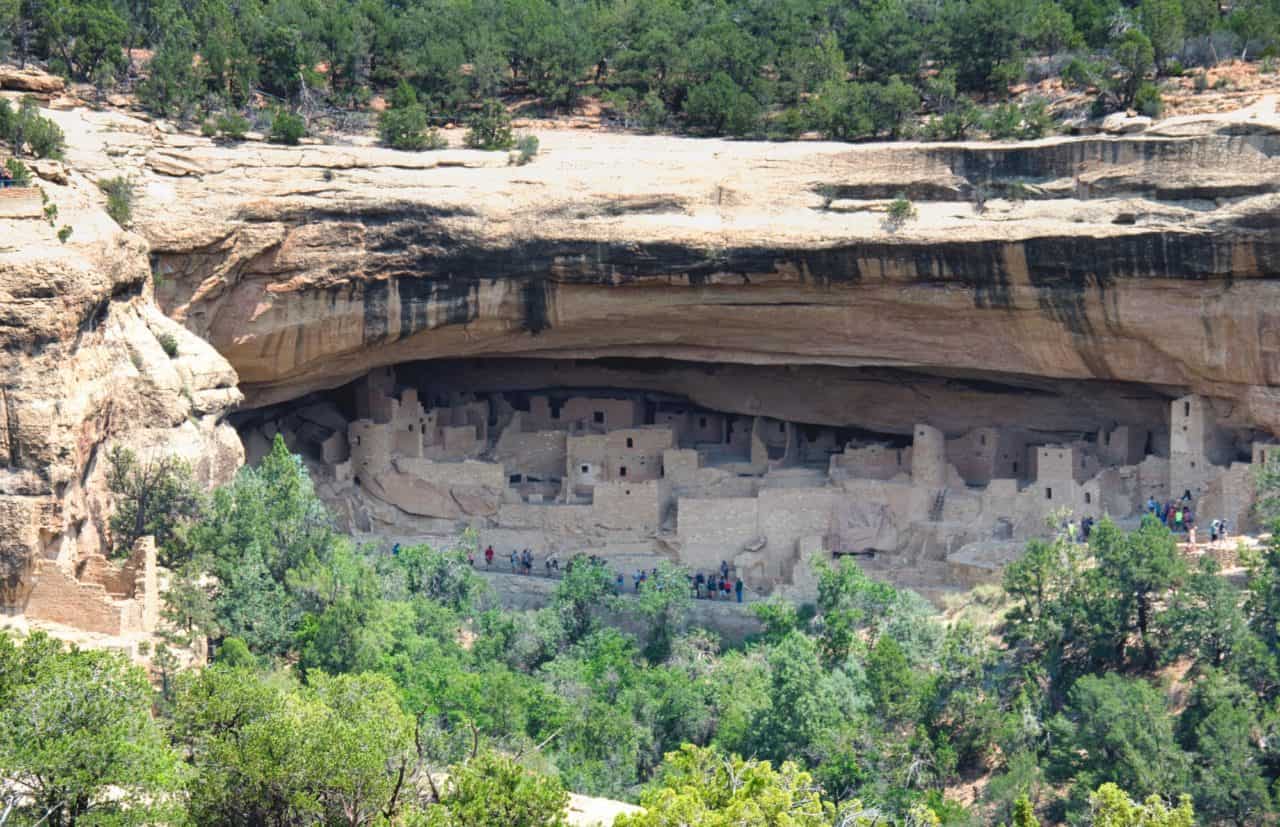

The climate of the western half of the North American continent, between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific coastal region, is dry by European standards. The American Southwest, in particular, centered roughly on the intersection of the states of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, is predominantly desert between high mountain plateaus. It is, and has always been, a challenging environment for farmers. Yet the prehistoric Southwest was home to complex maize-based agricultural societies. In fact, until the 19th century growth of industrial cities like New York, the Southwest contained ruins of the largest buildings north of Mexico — and these had been abandoned centuries before the Spanish arrived in the Americas.

© Mudwalker | Dreamstime.com

For more than a century, researchers have pored over data, from proxies of paleo-environmental change, to historiographies collected by explorers, to archaeology and computational models of human occupation, and produced a detailed picture of the socio-environmental, economic, and climatic conditions that could explain why these sites were abandoned. While details vary in fine-grained analyses of the various sub-groupings of peoples in the region, the big picture is one of societal transformation in adapting to climate change.

Also important is just how the climate changed during the period, because similar dynamics are expected to emerge in the future as a consequence of global warming. European historians point to a medieval era with generally warmer mean annual temperatures. In the Southwestern United States however, which is more sensitive to changes in drought than temperature, the period between roughly AD 850 to 1350 is known as the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA). The warm, dry MCA was followed by a long stretch of increased changes in the availability of water, known as the Little Ice Age (LIA). More frequent “warm droughts” at the end of the MCA, and generally increasing changes in water resources at the onset of the LIA, is thought to be a good analogy for future conditions in western North America.

When I had the good fortune to visit IIASA as a participant of the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) in 2016, I worked with research scholars Juraj Balkovič and Tamás Krisztin to develop a model of ancient Fremont Native American maize. The Fremont were an ancient forager-farmer people who lived in the vicinity of modern Utah. We used a climate model reconstruction of the temperature and rainfall between AD 850 and 1450 to drive this maize crop model, and compared modeled crop yields against changes in radiocarbon-derived occupations – in other words, the information gathered from carbon dated artifacts that show that an area was occupied by a particular people – from a few archaeological areas in Utah.

© Galyna Andrushko | Dreamstime.com

Among our findings was that changes in local temperatures appeared to play a larger role in the lives, practices and habits of the people who lived there than changes in regional, long-term temperature conditions [1]. Later, while a researcher at IIASA myself, I returned to the subject with one of our coauthors, professor Glen MacDonald of the University of California, Los Angeles, using an expanded geographic range and a more sophisticated treatment of radiocarbon dated occupation likelihoods.

We used the climate model to reconstruct prehistoric maize growing season lengths and mean annual rainfall for Fremont sites. We found that the most populous and resilient Fremont communities were at sites with low-variability season lengths; and low populations coincided with, or followed, periods of variable season lengths. This study confirmed the important dependence on climate variability; and more importantly, our results are in line with others on modern smallholder farming contexts.

More details on our latest study [2] have just been published online in Environmental Research Letters (ERL). It will become part of an ERL special issue looking at societal resilience drawing lessons from the past 5000 years. Studies like these can give useful insights on human societal responses to climate change because these ancient civilizations are, in a sense, completed experiments with complex human-environmental systems. For decision makers, who must plan early to commit resources to offset the effects of future climate change on smallholder farmers in similarly drought-sensitive, marginally productive environments, these studies indicate that year-to-year climatic variability drives occupation change more than long-term temperature change.

References:

[1] Thomson MJ, Balkovič J, Krisztin T, & MacDonald GM (2019). Simulated impact of paleoclimate change on Fremont Native American maize farming in Utah, 850–1449 CE, using crop and climate models. Quaternary International, 507, pp.95-107 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15472]

[2] Thomson MJ, & MacDonald GM (In press). Climate and growing season variability impacted the intensity and distribution of Fremont maize farmers during and after the Medieval Climate Anomaly based on a statistically downscaled climate model. Environmental Research Letters.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 14, 2020 | China, Environment, Food & Water, Water, Women in Science

By Maryna Strokal, Department of Environmental Sciences, Water Systems and Global Change, Wageningen University and Research, The Netherlands

Maryna Strokal discusses a new integrated approach to finding cost-effective solutions for nutrient pollution and coastal eutrophication developed with IIASA colleagues.

© Huy Thoai | Dreamstime.com

Have you ever wondered why the water in some rivers appear to be green? The green tinge you see is due to eutrophication, which means that too many nutrients – specifically nitrogen and phosphorus – are present in the water. This happens because rivers receive these nutrients from various land-based activities like run-off from agricultural fields and sewage effluents from cities. Rivers in turn export many of these nutrients to coastal waters, where it serves as food for algae. Too many nutrients, however, cause the algae and their blooms to grow more than normal. Because algae consumes a lot of oxygen, this lowers the available oxygen supply in the water, killing off fish and other marine life. Some algae can also be toxic to people when they eat seafood that have been exposed to, or fed on it. Polluted river water on the other hand, is unfit for direct use as drinking water, or for cooking, showering, or any of our other daily needs. Before we can use this water, it needs to be treated, which of course costs money.

To better understand and address these issues, I worked with colleagues from IIASA, Wageningen University, and China to develop an integrated approach to identify cost-effective solutions (read cheapest) to reduce river pollution and thus coastal eutrophication. Our integrated approach takes into account human activities on land, land use, the economy, the climate, and hydrology. We implemented the new approach for the Yangtze Basin in China.

The Yangtze is the third longest river in the world and exports nutrients from ten sub-basins to the East China Sea, where the coast often experiences severe eutrophication problems that may increase in the coming years. The Chinese government has called for effective actions to ensure clean water for both people and nature.

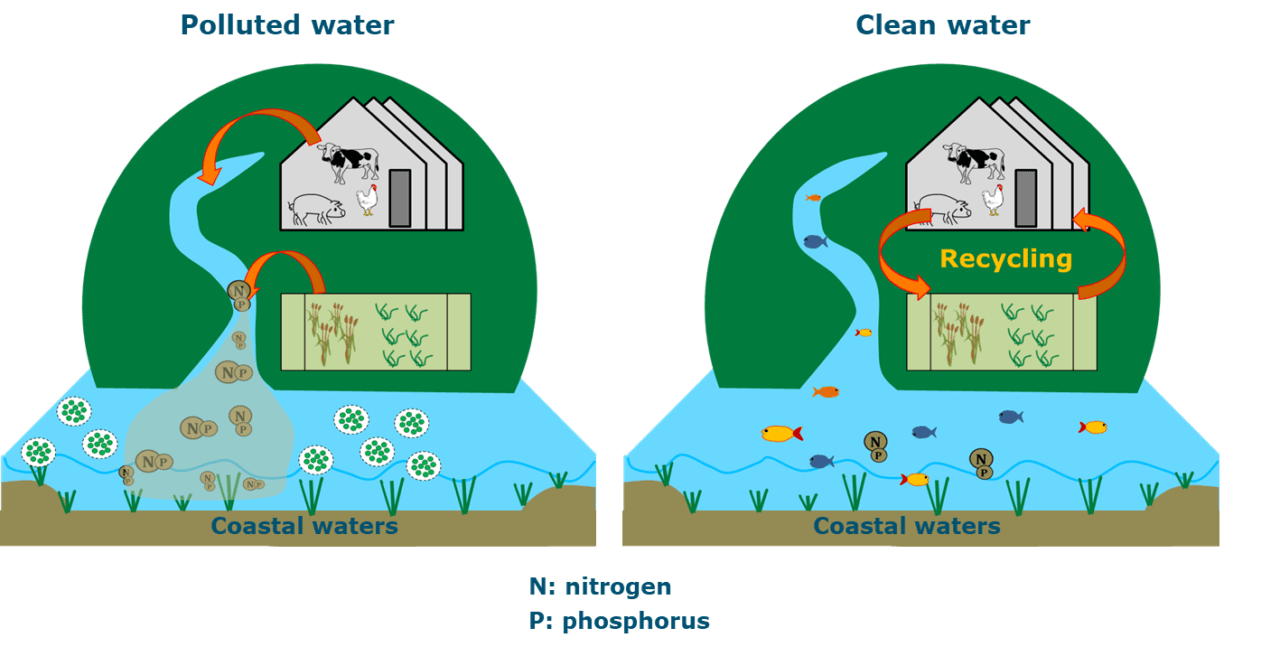

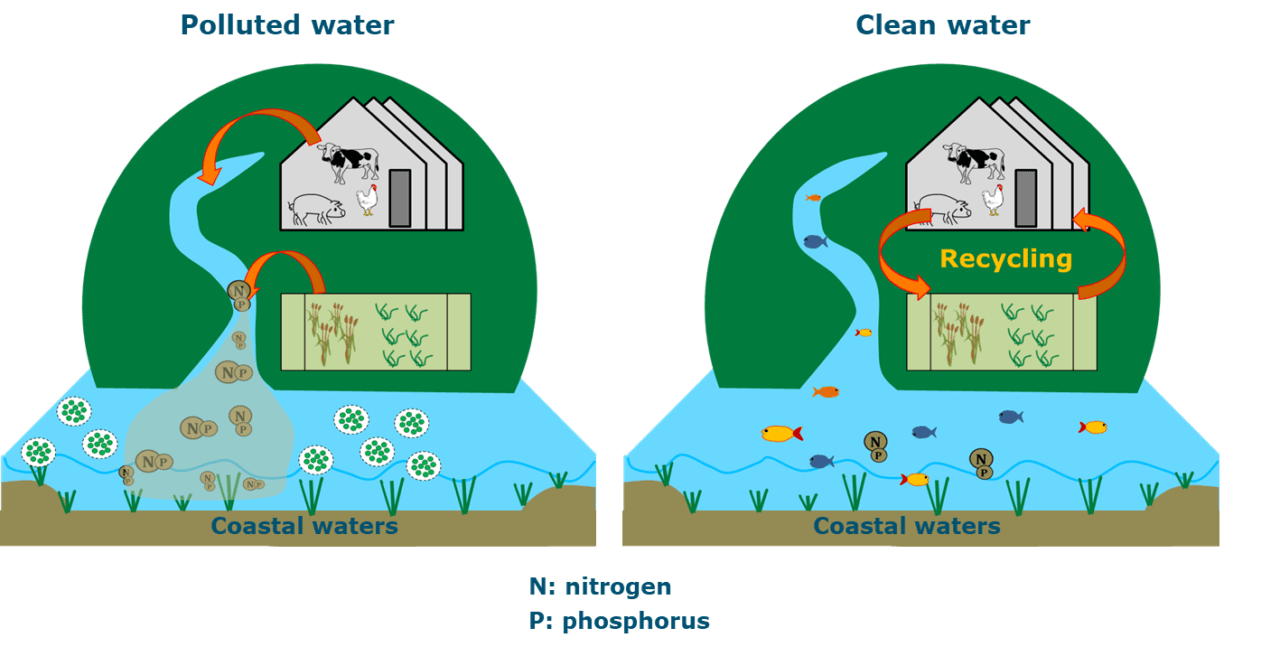

In our paper on this work, which was recently published in the journal Resources, Conservation, and Recycling, my colleagues and I conclude that reducing more than 80% of nutrient pollution in the Yangtze will cost US$ 1–3 billion in 2050. This cost might seem high, but it is actually far below 10% of the income level in the Yangtze basin. We also identified an opportunity in the negative or zero cost range, which would result in a below 80% reduction in nutrient export by the Yangtze. This negative or zero cost alternative involves options to recycle manure on land and reduce the use of chemical fertilizers (Figure 1). More recycling means that farmers will buy less chemical fertilizers and potential savings can then compensate for the expenses related to recycling the manure. We also illustrated the costs that would be involved for ten sub-basins to reduce their nutrient export to coastal waters.

Figure 1. Summarized illustration of eutrophication causes and cost-effective solutions for reducing nutrient export by Yangtze and thus coastal eutrophication in the East China Sea in 2050.

Recycling manure on cropland is an important and cost-effective solution for agriculture in the sub-basins of the Yangtze River (Figure 1). Manure is rich in the nutrients that crops need, and opting for this alternative instead of chemical fertilizers avoids loss of nutrients to rivers, and thus ultimately to coastal waters. Current practices are however still far from ideal, with manure – and especially liquid manure – often being discharged into water because crop and livestock farms are far away from each other, which makes it practically and economically difficult to transport manure to where it is needed. Another reason is the historical practice of farmers using chemical fertilizers on their crops – it is simply how they are used to doing things. Unfortunately, the amounts of fertilizers that farmers apply are often far above what crops actually need, thus leading to river pollution.

The Chinese government are investing in combining crop and livestock production, in other words, they are creating an agricultural sector where crops are used to feed animals and manure from the animals is in turn used to fertilize crops. Chinese scientists are working with farmers to implement these solutions.

In our paper, we showed that these solutions are not only sustainable, but also cost-effective in terms of avoiding coastal eutrophication. We invite you to read our paper for more details.

References

Strokal M, Kahil T, Wada Y, Albiac J, Bai Z, Ermolieva T, Langan S, Ma L, et al. (2020). Cost-effective management of coastal eutrophication: A case study for the Yangtze River basin. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 154: e104635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104635.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 4, 2019 | Ecosystems, Environment, IIASA Network

By Brian Fath, Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) scientific coordinator, researcher in the Advanced Systems Analysis Program, and professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Towson University (Maryland, USA) and Soeren Nors Nielsen, Associate professor in the Section for Sustainable Biotechnology, Aalborg University, Denmark

IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) scientific coordinator, Brian Fath and colleagues take an extended look at the application of the ecosystem principles to environmental management in their book, A New Ecology, of which the second edition was just released.

IIASA is known for some of the earliest studies of ecosystem dynamics and resilience, such as work done at the institute under the leadership of Buzz Holling. The authors of the book, A New Ecology, of which the second edition was just released, are all systems ecologists, and we chose to use IIASA as the location for one of the brainstorming meetings to advance the ideas outlined in the book. At this meeting, we crystallized the idea that ecosystem ontology and phenomenology can be summarized in nine key principles. We continue to work with researchers at the institute to look for novel applications of the approach to socioeconomic systems – such as under the current EU project, RECREATE – in which the Advanced Systems Analysis Program is participating. The project uses ecological principles to study urban metabolism – a multi-disciplinary and integrated platform that examines material and energy flows in cities as complex systems.

IIASA is known for some of the earliest studies of ecosystem dynamics and resilience, such as work done at the institute under the leadership of Buzz Holling. The authors of the book, A New Ecology, of which the second edition was just released, are all systems ecologists, and we chose to use IIASA as the location for one of the brainstorming meetings to advance the ideas outlined in the book. At this meeting, we crystallized the idea that ecosystem ontology and phenomenology can be summarized in nine key principles. We continue to work with researchers at the institute to look for novel applications of the approach to socioeconomic systems – such as under the current EU project, RECREATE – in which the Advanced Systems Analysis Program is participating. The project uses ecological principles to study urban metabolism – a multi-disciplinary and integrated platform that examines material and energy flows in cities as complex systems.

Our book argues the need for a new ecology grounded in the first principles of good science and is also applicable for environmental management. Advances such as the United Nations Rio Declaration on Sustainable Development in 1992 and the more recent adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (2015) have put on notice the need to understand and protect the health and integrity of the Earth’s ecosystems to ensure our future existence. Drawing on decades of work from systems ecology that includes inspiration from a variety of adjacent research areas such as thermodynamics, self-organization, complexity, networks, and dynamics, we present nine core principles for ecosystem function and development.

The book takes an extended look at the application of the ecosystem principles to environmental management. This begins with a review of sustainability concepts and the confusion and inconsistencies of this is presented with the new insight that systems ecology can bring to the discussion. Some holistic indicators, which may be used in analyzing the sustainability states of environmental systems, are presented. We also recognize that ecosystems and society are physically open systems that are in a thermodynamic sense exchanging energy and matter to maintain levels of organization that would otherwise be unattainable, such as promoting growth, adaptation, patterns, structures, and renewal.

Another fundamental part of the evolution of the just mentioned systems are that they are capable of exhibiting variation. This property is maintained by the fact that the systems are also behaviorally open, in brief, capable of taking on an immense number of combinatorial possibilities. Such an openness would immediately lead to a totally indeterminate behavior of systems, which seemingly is not the case. This therefore draws our attention towards a better understanding of the constraints of the system.

One way of exploring the interconnectivity in ecosystems is taking place mainly through the lens of ecological network analysis. A primer for network environment analysis is provided to familiarize the reader with notation including worked examples. Inherent in energy flow networks, such as ecosystem food webs, the real transactional flows give rise to many hidden properties such as the rise in indirect pathways and indirect influence, an overall homogenization of flow, and a rise in mutualistic relations, while hierarchies represent conditions of both top-down and bottom-up tendencies. In ecosystems, there are many levels of hierarchies that emerge out of these cross-time and space scale interactions. Managing ecosystems requires knowledge at several of these multiple scales, from lower level population-community to upper level landscape/region.

Viewing the tenets of ecological succession through a lens of systems ecology lends our attention the agency that drives the directionality stemming from the interplay and interactions of the autocatalytic loops – that is, closed circular paths where each element in the loop depends on the previous one for its production – and their continuous development for increased efficiency and attraction of matter and energy into the loops. Ecosystems are found to show a healthy balance between efficiency and redundancy, which provides enough organization for effectiveness and enough buffer to deal with contingencies and inevitable perturbations.

Yet, the world around us is largely out of equilibrium – the atmosphere, the soils, the ocean carbonates, and clearly, the biosphere – selectively combine and confine certain elements at the expense of others. These stable/homoeostatic conditions are mediated by the actions of ecological systems. Ecosystems change over time displaying a particular and identifiable pattern and direction. Another “unpleasant” feature of the capability for change is to further evolve through collapses. Such collapse events open up creative spaces for colonization and the emergence of new species and new systems. This pattern includes growth and development stages followed by the collapse and subsequent reorganization and launching to a new cycle.

A good theory should be applicable to the concepts in the field it is trying to influence. While the mainstream ecologists are not regularly applying systems ecology concepts, the purpose of our book is to show the usefulness of the above ecosystem principles in explaining standard ecological concepts and tenets. Case studies from the general ecology literature are given relating to evolution, island bio-geography, biodiversity, keystone species, optimal foraging, and niche theory to name a few.

No theory is ever complete, so we invite readers to respond and comment on the ideas in the book and offer feedback to help improve the ideas, and in particular the application of these principles to environmental management. We see a dual goal to understand and steward ecological resources, both for their sake and our own, with the purpose of an ultimate sustainability.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 21, 2019 | Air Pollution, Environment, Food & Water, Indonesia, Women in Science

By Adriana Gómez-Sanabria, researcher in the IIASA Air Quality and Greenhouse Gases Program

Adriana Gómez-Sanabria discusses the results of a new study that looked into the impacts of implementing various technologies to treat wastewater from the fish processing industry in Indonesia.

© Mikhail Dudarev | Dreamstime.com

To reduce water pollution and climate risks, the world needs to go beyond signing agreements and start acting. Translating agreements and policies into action is however always much more difficult than it might seem, because it requires all players involved to participate. A complete integration strategy across all sectors is needed. One of the advantages of integrating all sectors is that it would be possible to meet different objectives, for example, climate and water protection goals in this case, with the same strategy.

I was involved in a study that assessed the impacts of implementing various technologies to treat wastewater from the fish processing industry in Indonesia when involving different levels of governance. This study is part of the strategies that the government of Indonesia is evaluating to meet the greenhouse gas mitigation goals pledged in its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), as well as to reduce water pollution. Although Indonesia has severe national wastewater regulations, especially in the fish processing industry, these are not being strictly implemented due to lack of expertise, wastewater infrastructure, budgetary availability, and lack of stakeholder engagement. The objective of the study was to evaluate which technology would be the most appropriate and what levels of governance would need to be involved to simultaneously meet national climate and water quality targets in the country.

Seven different wastewater treatment technologies and governance levels were included in the analysis. The combinations included were: 1) Untreated/anaerobic lagoons – where untreated means wastewater is discharged without any treatment and anaerobic lagoons are ponds filled with wastewater that undergo anaerobic processes – combined with the current level of governance. 2) Aeration lagoons – which are wastewater treatment systems consisting of a pond with artificial aeration to promote the oxidation of wastewaters, plus activated sludge focused solely on water quality targets with no coordination between water and climate institutions. 3) Swimbed, which is an aerobic aeration tank focusing mainly on climate targets assuming no coordination between institutions. 4) Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) technology, which is an anaerobic reactor with gas recovery and use followed by Swimbed, and 5) UASB with gas recovery and use followed by activated sludge, which is an aerobic treatment that uses microorganisms forming particles that clump together. Both, 4 and 5 assume vertical and horizontal coordination between water and climate institutions at national, regional, and local level. It is important to notice that the main difference between 4 and 5 is the technology used in the second step. Two additional combinations, 6 and 7, are also proposed including the same technological combinations of 4 and 5, but these include increasing the level of governance to a multi-actor coordination level. The multi-actor level includes coordination at all institutional levels but also involves academia, research institutes, international support, and other stakeholders.

Our results indicate that if the current situation continues, there would be an increase of greenhouse gases and water pollution between 2015 and 2030, driven by the growth in fish industry production volumes. Interestingly, the study also shows that focusing only on strengthening capacities to enforce national water policies would result in greenhouse gas emissions five times higher in 2030 than if the current situation continues, due to the increased electricity consumption and sludge production from the wastewater treatment process. The benefit of this strategy would be positive for the reduction of water pollution, but negative for climate change mitigation. From our analyses of combinations 2 and 3 we learned that technology can be very efficient for one purpose but detrimental for others. If different institutions are, for example, responsible for water quality and climate change mitigation, communication between the institutions is crucial to avoid trade-offs between environmental objectives.

Furthermore, when analyzing different cooperation strategies together with a combination of diverse sets of technologies, we found that not all combinations work appropriately. For instance, improving interaction just within and between institutions does not guarantee proper selection and application of technologies. In this case, the adoption of the technology is not fast enough to meet the targets proposed in 2030, thus resulting in policy implementation failures. Our analyses of combinations 4 and 5 showed that interaction within and between national, regional, and local institutions alone is not enough to prevent policy failure.

Finally, a multi-actor cooperation strategy that includes cooperation across sectors, administrative levels, international support, and stakeholders, seems to be the right approach to ensure selection of the most appropriate technologies and achieve policy success. We identified that with this approach, it would be possible to reduce water pollution and simultaneously decrease greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity required for wastewater treatment. Analyzing combinations 6 and 7 revealed that multi-actor governance allows to simultaneously meet climate and water objectives and a high chance to prevent policy failure.

In the end, analyses such as the one shown here, highlight the importance of integrating and creating synergies across sectors, administrative levels, stakeholders, and international institutions to ensure an effective implementation of policies that provide incentives to make careful choices regarding multi-objective treatment technologies.

Reference:

Gómez-Sanabria A, Zusman E, Höglund-Isaksson L, Klimont Z, Lee S-Y, Akahoshi K, Farzaneh H, & Chairunnisa (2019). Sustainable wastewater management in Indonesia’s fish processing industry: bringing governance into scenario analysis. Journal of Environmental Management (Submitted).

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 23, 2019 | Ecosystems, Environment, Sustainable Development

By Frank Sperling, Senior Project Manager (FABLE) in the IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Food and land use systems play a critical role in managing climate risks and bringing the world onto a sustainable development trajectory.

The UN Secretary General’s Climate Action Summit in New York on 23 September seeks to catalyze further momentum for climate change mitigation and adaptation. The transformation of the food and land use system will play a critical role in managing climate risks and bringing the world onto a sustainable development trajectory.

Today’s food and land use systems are confronted with a great variety of challenges. This includes delivering on universal food security and better diets by 2030. Over the last decades, great strides have been made towards achieving universal food security, but this progress recently grinded to a halt. The number of people suffering from chronic hunger has been rising again from below 800 million in 2015 to over 820 million people today [1]. Food security is however not only about a sufficient supply of calories per person. It is also about improving diets, addressing the worldwide increase in the prevalence of obesity, and how we use and value environmental goods and services.

© Paulus Rusyanto | Dreamstime.com

Agriculture, forestry and other land use currently account for around 24% of greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activities [2]. Land use changes are also a major driver behind the worldwide loss of biodiversity [3]. Clearly, in light of population growth and the increasingly visible fingerprints of a human-induced global climate crisis and other environmental changes, business as usual is not an option.

Systems thinking is key in shifting towards more sustainable practices. A new report released by the Food and Land-Use System (FOLU) Coalition showcases that there is much to be gained. There are massive hidden costs in our current food and land use systems. The report outlines ten critical transitions, which can substantially reduce these hidden costs, thereby generating an economic prize, while improving human and planetary health.

The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) contributed to the analytics underpinning the report [4], applying the Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM) [5]. A “better futures” scenario, which seeks to collectively address development and environmental objectives, was compared to a “current trends” scenario, which is basically a continuation of a business-as-usual scenario. The assessment illustrates that an integrated approach that acknowledges the interactions in the food and land use space, can help identify synergies and manage trade-offs across sectors. For example, shifting towards healthy diets not only improves human health, but also reduces pressure on land, thereby helping to improve the solution space for addressing climate change and halting biodiversity loss.

While understanding that the global picture is important, practical solutions require engagement with national and subnational governments. The challenge is to identify development pathways that address the development needs and aspirations of countries within global sustainability contexts. As part of FOLU, the Food, Agriculture, Biodiversity, Land and Energy (FABLE) Consortium was initiated to do exactly this. The FABLE Secretariat, jointly hosted by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) and IIASA, is working with knowledge institutions from developed and developing countries, to explore the interactions between national and global level objectives and their implications for pathways towards sustainable food and land use systems. Preliminary results from inter-active scenario and development planning exercises, so-called Scenathons, were recently presented in the FABLE 2019 report.

These initiatives highlight that acknowledging and embracing complexity can help reconcile development and environmental interests. This also entails rethinking how we relate to and manage nature’s services and their role in providing the foundation for the welfare of current and future generations. This is underscored by the prominent role nature-based solutions are given at the UN Secretary General’s Climate Action Summit. We need to move from silo-based, sector specific, single objective approaches to a focus on multiple objective solutions. In the land use space, this means embedding agriculture in the broader land use context, which accounts for and values environmental services, and linking to the food system where dietary choices shape human health and the demand for land.

Doing so will help bridge the international policy objectives of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the UN Convention on Combating Desertification (UNCCD), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) enshrined in ‘The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’. This represents an opportunity to create a new value proposition for agriculture and other land use activities where environmental stewardship is rewarded.

References

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) et al. (2019). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019. Safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns. Rome, FAO.

[2] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2019). Climate Change and Land. IPCC Special Report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

[3] Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (2018). The IPBES assessment report on land degradation and restoration. Montanarella, L., Scholes, R., and Brainich, A. (eds.). Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, Germany. 744 pages.

[4] Deppermann, A. et al. 2019. Towards sustainable food and land-use systems: Insights from integrated scenarios of the Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM). Supplemental Paper to The 2019 Global Consultation Report of the Food and Land Use Coalition Growing Better: Ten Critical Transitions to Transform Food and Land Use. Laxenburg, IIASA.

[5] Havlik P, Valin H, Herrero M, Obersteiner M, Schmid E, Rufino MC, Mosnier A, Thornton PK, et al. (2014). Climate change mitigation through livestock system transitions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (10): 3709-3714. DOI: 1073/pnas.1308044111 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/10970].

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.