Jul 20, 2018 | Systems Analysis, Water, Young Scientists

By Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Imagine you are heading home from work and are stuck in evening rush hour traffic. You see an opportunity to save time by cutting another driver off, but this will lead to a delay for other cars, possibly causing a traffic jam. Would you do it? Situations like these, where you can benefit from acting selfishly while causing the community as a whole to be worse off, are known as social dilemmas, and are at the heart of many areas of research in economics.

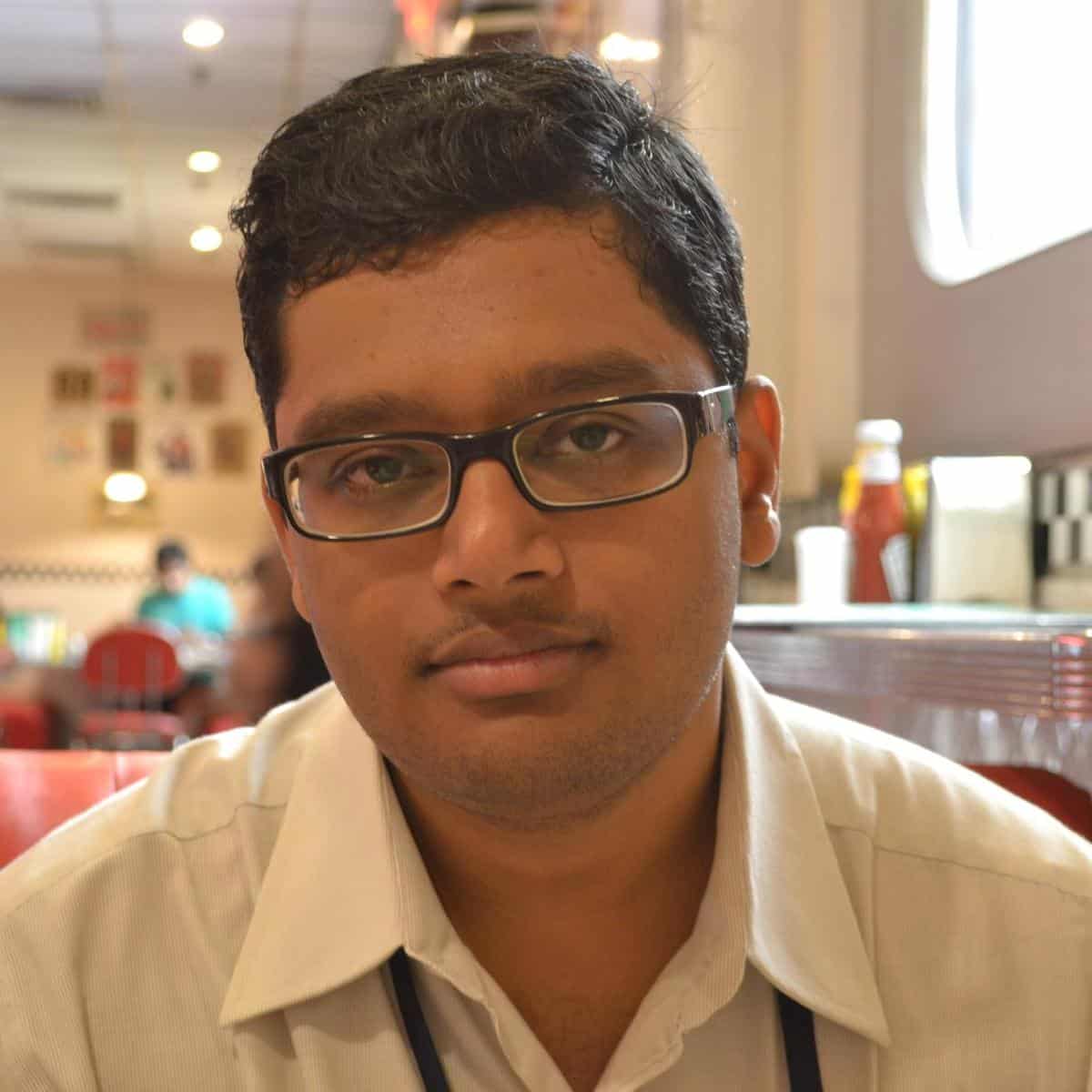

Tum Nhim (left) discusses water sharing with farmers and local authorities in rural Cambodia. © Tum Nhim

The social dilemma becomes particularly important when considering so-called common pool resources such as water reservoirs that are depleted when people use them. For instance, picture several farmers using water from the same river to irrigate their farmland. The river might carry enough water for all of them, but if there is no incentive for the upstream farmers to take the needs of the farmers living further downstream into consideration, they might use more than their share of the water, not leaving enough for the rest of the group. Situations like this are particularly relevant in developing countries, where small-scale farmers that manage the irrigation of their farmland themselves play a significant role in ensuring food security.

Growing up in southwestern Cambodia, YSSP participant Tum Nhim saw how the surrounding farmers shared water among themselves, and how important water was to their livelihoods. Not having enough water often meant that there were no crops for a whole year, and many farmers were forced to take on loans in order to feed their families. “Now that climate change is starting to affect Cambodia, and water scarcity is becoming an even bigger problem, it is more important than ever to investigate fair and efficient ways of sharing water,” explains Nhim.

As a water engineer, Nhim used to design and build water infrastructure. He however soon learned that not considering how human decision making affects the water supply will cause situations where the infrastructure provides enough water, but some farmers are still left high and dry. “I think that human behavior is the most important factor to consider when managing common pool resources,” he says.

To find possible solutions for distributing water in a way that yields an optimal outcome for the community, Nhim and his colleagues from the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program use a bottom-up approach–they model the behavior of a number of individual farmers that interact according to certain rules. The researchers can then look at the collective outcome of these interactions after a certain time and ask questions like, “Will the farmers cooperate?” or, “Will some farmers be left without water?” In their model the researchers take into account both the water itself, a common pool resource, and the water infrastructure, which is not depleted by use.

Several mechanisms can be used to ensure the fair distribution of water. Some of them are formal; like laws and regulations, but it is often difficult to keep people from extracting water, because using a given water resource might be a long-standing cultural tradition or legal right. There are however also more informal mechanisms that can help. For example, individuals often prefer to be good citizens in order to ensure that they have a high social standing in their community that will bring them benefits.

This reputational mechanism is especially relevant in small communities with everyday contact between members. If someone takes too much water, or doesn’t invest in the common water infrastructure, they will gain a bad reputation, which will in turn limit their ability to get support from their neighbors later on.

The main question Nhim is investigating in his YSSP project is if this mechanism can spread across several villages that share a common water resource and irrigation infrastructure, and lead to an outcome where everyone cooperates. If this turns out to be true, the reputational mechanism could be a very inexpensive and natural solution for managing common goods across several communities.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 17, 2018 | Air Pollution, Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science, Young Scientists

© Stefano Barzellotti | Shutterstock

By Sandra Ortellado, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

When it comes to home cooking in rural India, health, behavior, and technology are essential ingredients.

Consider the government’s three-year campaign to reduce the damaging impacts of solid fuels traditionally used in rural households below the poverty line.

Initiated by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, a program called Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (Ujjwala) aims to safeguard the health of women and children by providing them access to a clean cooking fuel, liquid petroleum gas (LPG), so that they don’t have to compromise their health in smoky kitchens or wander in unsafe areas collecting firewood.

According to the World Health Organization, smoke inhaled by women and children from unclean fuel is equivalent to burning 400 cigarettes in an hour.

Nevertheless, an estimated 700 million people in India still rely on solid fuels and traditional cooking stoves in their homes. A subsidy of Rs. 1600 (US $23.47) and an interest free loan attempts to offset the discouraging cost of the upfront security deposit, the stove, and the first bottle of LPG, but this measure hasn’t been able to change habits on its own.

Why? Although the government has made an overwhelming effort to increase access, interconnected factors like cultural norms, economic trade-offs, and convenience require an in-depth analysis of human behavior and decision-making.

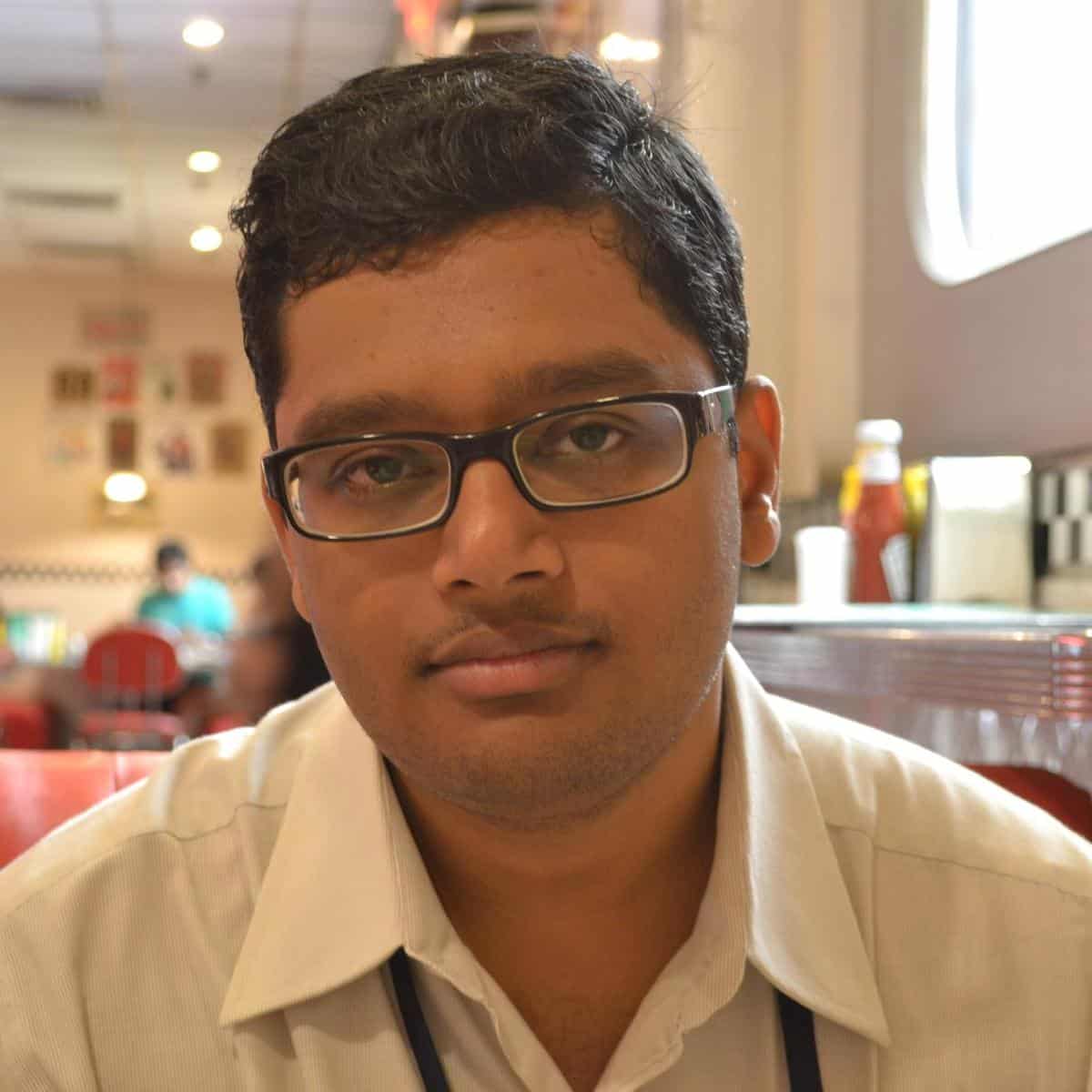

Abhishek Kar, 2018 YSSP participant ©IIASA

That’s why Abhishek Kar, a researcher in the IIASA Energy Program and a participant in the 2018 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), has designed a study to explore how rural households make choices about access and usage. Borrowing from behavior change and technology adoption theories, he wants to know whether low-cost access is enough incentive for Ujjwala beneficiaries to match the general rural consumption trends, and more importantly, how to translate public perception into a behavior change.

“I think it’s really important to look into the behavioral aspect,” said Kar in an interview. “If you ask someone if they think clean cooking is wise they may say yes, but if you say do you think it is appropriate for you? The moment it becomes personalized the answers can vary.”

Kar knows that although more than 41 million LPG connections have been installed, installment of the connection does not necessarily equate to use. By gathering data on LPG refill purchases and trends, along with surveys that identify biases in the public’s perception, he wants to know how to convince rural BPL households to maintain the habit of using LPG regularly, even under adverse conditions like price hikes. If LPG is used only sporadically, LPG ownership won’t significantly reduce risk for some household air pollution (HAP)-linked deadly diseases, like lower respiratory infections and stroke.

Unfortunately, even the substantial efforts the government has made to improve LPG supply has not changed the public’s perception of its accessibility in the long term, nor its consumption patterns in the first two years. At least four LPG refills per year would be needed for a family of five to use LPG as a primary cooking fuel, which is not currently happening for the majority of Ujjwala customers.

Because the majority of Ujjwala beneficiaries have cost-free access to solid fuels from forest and agricultural fields, there is less incentive for these families to use LPG regularly instead of sporadically. Priority households for Ujjwala, especially those with no working age adults, are often severely economically disadvantaged and can’t afford to buy LPG at regular intervals.

Furthermore, unlike LPG, a traditional mud stove is more versatile and can serve dual purposes of space heating and cooking during winter months. Many prospective customers are also hesitant about the inferior taste of food cooked in LPG, the utility of the mud stove’s smoke as insect repellent, and the trade-off of expenses on tobacco and alcohol with LPG refills.

As per past studies, even the richest 10% of India’s rural households (most with access to LPG) continue to depend on solid fuels to meet ~50% of their cooking energy demand. This suggests that wealth is not the only stumbling block in the transition process.

“Whatever factors matter in the outside world, my working hypothesis is that every decision is finally mediated through a person’s attitude, knowledge, and perceptions of control,” said Kar. According to Kar, interventions can be specifically targeted to address factors that are perceived negatively either by informing people or doing something to improve that factor. Nevertheless, developing effective interventions is no simple task.

Even with a background in physics and management and eight years of experience helping people transition from one technology to another, Kar says he is grateful to have the input of a variety of scholars at IIASA, each with a different perspective and a different set of core skills and experiences. Working in the Energy program alongside IIASA staff and fellow YSSPers from all over the world, Kar puzzles out the unsolved challenge of how to create change for the rural poor.

“That has been one of my drivers, I take it as an intellectual challenge,” said Kar. “Is there a systems approach to the problem?”

For now, Kar is happy if he can return at the end of the day to his family, which he brought with him to Austria during his time as a YSSP participant, feeling like he is opening the door to a vast literature on technology adoption and human behavior, yet untapped in the field of cooking energy access.

“This research is only a very small baby step into trying something different,” said Kar, “I think this sector has so many unanswered questions, if I can at least flag that there is a lot of literature out there in other domains and maybe we can use some of it, I think that would be good enough for me.”

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 12, 2018 | Climate Change, Science and Policy, Young Scientists

by Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Kian Mintz-Woo is a moral philosopher working in the field of climate ethics. He obtained his PhD from the University of Graz and is spending the summer at IIASA as a participant of the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP). I recently had the opportunity to talk to him about his work.

Kian Mintz-Woo, © Kedar Kulkarni | IIASA

How do you feel about joining YSSP as a philosopher?

I know that it is extremely unusual for a philosopher to join YSSP, and I’m really happy to be here. It is very stimulating to be surrounded by people with a different point of view. I appreciate that people are asking me about what philosophers do, or they’ve come across a philosophical text and want to know my opinion. It is extremely valuable to me to talk about my discipline to interested people.

You started out studying logic – how did you become interested in climate change?

I used to do research on abstract and systematic areas of mainstream philosophy. I enjoyed it, but was also interested in social issues. I think climate change is particularly important, because unlike most issues we have a very short time window to deal with it. Of course there are a lot of things we have to change in our society, but climate change is definitely an issue that can’t be put off anymore.

When I started my BPhil in Oxford, I initially worked on similarly abstract topics, but then I met John Broome, an expert in climate ethics. Doing a project with him was both a once-in-a -lifetime-opportunity and a possibility to marry my theoretical training with some of my real-world interests. What I am doing now is about as applied as philosophy can get—I’m on the edge of what some people would even call philosophy—and it is great fun!

What is your project about?

When talking about climate change, we often discuss two things: ways to limit the temperature increase on earth (mitigation), and ways to adapt to the changing conditions that accompany climate change (adaptation). However, we also increasingly have to consider effects of climate change that go beyond what we are able or willing to adapt to. We call this area of research and policy “Loss and Damage”.

We have to think about who is responsible for the Loss and Damage-related burdens that we are and will be facing. In my project, I argue that, conceptually, there is a strong link between historical responsibility for emissions of greenhouse gases and Loss and Damage. This is very relevant for policy as well: We don’t want the farmer who can no longer support himself because changing rain patterns have reduced his crop yield, or the small island nation that might be flooded in the future, to bear the risks related to climate change alone. However, the instruments that can help spread this risk globally require financial burdens.

Most of the discussions about who should be the bearers of these burdens have been in terms of nations, but an interesting paper from 2014 suggests that we should rethink that approach. The main findings of this paper are that only 90 companies producing oil, natural gas, coal, and cement were the source of 63% of historical CO2 emissions. As the number of these so-called carbon majors is so surprisingly small, considering them instead of nations in the discussions about funding might be a valid alternative.

Is it relevant if the effects of these emissions were known at the time?

That is an important question and I think that it should matter. The data we have goes back to 1854, so I feel that at least some of the time the emissions should be considered under the heading of excusable ignorance. We could start holding the carbon majors responsible after a certain year, maybe around 1980 or 1990, and part of my research is finding out how the selection of the carbon majors depends on the chosen point.

How does your work relate to the research going on in the IIASA RISK Program?

It is great being in the RISK group. My input as a philosopher is making conceptual suggestions and bringing in fairly blue-sky policy solutions. What I am getting from my supervisors are real-world implications of these suggestions, such as risk instruments that might be relevant for the implementation of my ideas. So together, we are aiming to make these abstract ideas policy-relevant.

Why should we apply philosophical concepts to problems like climate change?

Science can help us figure out which pathways are available, but scientists are often not very well trained in evaluating those beyond their economic-technical approach. Moral philosophers can bring in new perspectives for evaluating these options.

What I am doing at IIASA however, is taking a step back from the research that is going on in order to ask fundamental questions. I want to provide ambitious proposals, and find out what they would push us towards if we were trying to implement them. This often requires bringing concepts and results together from different areas of research to obtain a broader view on the problem.

What do you want to achieve by the end of the summer?

I hope to achieve a policy proposal that is ambitious but defensible. I want to develop a clear argument as to why the carbon majors are more responsible for Loss and Damage than for mitigation and adaptation. I think this approach is both new and quite important, especially for many developing countries and small island states.

Apart from your research project, what are you looking forward to most this summer?

I am getting married this month, so this is an especially exciting and busy summer for me!

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 9, 2018 | Alumni, Communication, IIASA Network, South Africa, Systems Analysis, Young Scientists

By Sandra Ortellado, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2018

In 2007, Sepo Hachigonta was a first-year PhD student studying crop and climate modeling and member of the YSSP cohort. Today, he is the director in the strategic partnership directorate at the National Research Foundation (NRF) in South Africa and one of the editors of the recently launched book Systems Analysis for Complex Global Challenges, which summarizes systems analysis research and its policy implications for issues in South Africa.

From left: Gansen Pillay, Deputy Chief Executive Officer: Research and Innovation Support and Advancement, NRF, Sepo Hachigonta, Editor, Priscilla Mensah, Editor, David Katerere, Editor, Andreas Roodt Editor

But the YSSP program is what first planted the seed for systems analysis thinking, he says, with lots of potential for growth.

Through his YSSP experience, Hachigonta saw that his research could impact the policy system within his home country of South Africa and the nearby region, and he forged lasting bonds with his peers. Together, they were able to think broadly about both academic and cultural issues, giving them the tools to challenge uncertainty and lead systems analysis research across the globe.

Afterwards, Hachigonta spent four years as part of a team leading the NRF, the South African IIASA national member organization (NMO), as well as the Southern African Young Scientists Summer Program (SA-YSSP), which later matured into the South African Systems Analysis Centre. The impressive accomplishments that resulted from these programs deserved to be recognized and highlighted, says Hachigonta, so he and his colleagues collected several years’ worth of research and learning into the book, a collaboration between both IIASA and South African experts.

“After we looked back at the investment we put in the YSSP, we had lots of programs that were happening in South Africa, and lots of publications and collaboration that we wanted to reignite,” said Hachigonta. “We want to look at the issues that we tackled with system analysis as well as the impact of our collaborations with IIASA.”

Now, many years into the relationship between IIASA and South Africa, that partnership has grown.

Between 2012 and 2015, the number of joint programs and collaborations between IIASA and South Africa increased substantially, and the SA-YSSP taught systems analysis skills to over 80 doctoral students from 30 countries, including 35 young scholars from South Africa.

In fact, several of the co-authors are former SA-YSSP alumni and supervisors turned experts in their fields.

“We wanted to use the book as a barometer to show that thanks to NMO public entity funding, students have matured and developed into experts and are able to use what they learned towards the betterment of the people,” says Hachigonta. The book is localized towards issues in South Africa, so it will bring home ideas about how to apply systems analysis thinking to problems like HIV and economic inequality, he adds.

“It’s not just a modeling component in the book, it still speaks to issues that are faced by society.”

Complex social dilemmas like these require clear and thoughtful communication for broader audiences, so the abstracts of the book are organized in sections to discuss how each chapter aligns systems analysis with policymaking and social improvement. That way, the reader can look at the abstract to make sense of the chapter without going into the modeling details.

“Systems analysis is like a black box, we do it every day but don’t learn what exactly it is. But in different countries and different sectors, people are always using systems analysis methodologies,” said Hachigonta, “so we’re hoping this book will enlighten the research community as well as other stakeholders on what systems analysis is and how it can be used to understand some of the challenges that we have.”

“Enlightenment” is a poetic way to frame their goal: recalling the age of human reason that popularized science and paved the way for political revolutions, Hachigonta knows the value of passing down years of intellectual heritage from one cohort of researchers to the next.

“You are watching this seed that was planted grow over time, which keeps you motivated,” says Hachigonta.

“Looking back, I am where I am now because of my involvement with IIASA 11 years ago, which has been shaping my life and the leadership role I’ve been playing within South Africa ever since.”

Jun 18, 2018 | Alumni, Ecosystems, Environment, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Cecile Godde, PhD student at the University of Queensland, Australia and former IIASA YSSP participant

Cecile Godde ©Oli Sansom

Last year, I had the fantastic opportunity to spend three months at IIASA as part of the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), to collaborate with the Ecosystems Services and Management (ESM) research program. During this very enriching experience, both intellectually, socially, and culturally, I worked with Petr Havlik, David Leclère, and Christian Folberth on modeling global rangelands and pasturelands under farming and climate scenarios. I also progressed on the development of a global animal stocking rate optimizer. The overall objective of this YSSP project, and more broadly of my PhD, is to assess the role of grazing systems in a sustainable food system.

However, my trip to IIASA was not my only adventure last year. Just before moving to Vienna, I received the great news that I was selected along with 77 other women to take part in a women in science and leadership program called Homeward Bound.

What would our world look like if women and men were equally represented, respected, and valued at the leadership table? How might we manage our resources and our communities differently? How might we coordinate our response to global problems like food security and climate change?

Homeward Bound is a worldwide and world-class initiative that seeks to support and encourage women with scientific backgrounds into leadership roles, believing that diversity in leadership is key to addressing these complex and far-reaching issues. The program’s bold mission is to create a 1000-strong collective of women in science around the world over the next 10 years, with the enhanced leadership, strategic, and visibility capacity to influence policy and decision making for the benefit of the planet.

Antarctic penguins © Cecile Godde

This year-long program culminated in an intensive three-week training course in Antarctica, a journey from which I have just come back. The voyage to Antarctica was incredible. We learnt intensively during this 24/7 floating conference in the midst of majestic icebergs, very cute penguins, graceful whales, and extraordinary women from various cultures and backgrounds, from PhD students to Nobel Laureates. I have returned full of hope for the planet, deeply inspired, and emotionally energized. It was a truly unforgettable experience, one that will keep me reflecting for a lifetime.

Our days in Antarctica typically followed a similar routine – half of the day was dedicated to a landing (we visited Argentinian, Chinese, US, and UK research stations) and the other half to classes and workshops. We discussed systemic gender issues and learnt about leadership styles, peer-coaching, the art of providing feedback, science communication, core personal values, or what matter to us. The list goes on! We were also encouraged to practice reflective journaling. Regularly recording activities, situations, and thoughts on paper is actually a very powerful technique for self-discovery and personal and professional growth as it helps us think in a critical and analytical way about our behaviors, values, and emotions. We also spent quite some time developing our personal and professional strategies: What is our purpose as individuals? What are our core values, aspirations, and short- and long-term goals? From that, we developed a roadmap that could be executed as soon as we stepped off the ship. While I haven’t solved all my life’s mysteries, this activity gave me strong foundations to keep growing and actively shape my own life, rather than letting society do it for me.

In the evenings, we watched our film faculty sharing their tips with us on television, including primatologist Jane Goodall, world leading marine biologist Sylvia Earle, and former Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC), Christiana Figueres. We also had a collective art project called “Confluence: A Journey Homeward Bound”, which was underpinned by our inner journey of reflection, growth, and transformation and our outer physical journey to Antarctica.

Homeward Bound in Antarctica © Oli Sansom

Both my stay at IIASA and my journey to Antarctica taught me a lot about the value of getting out of my comfort zone, exploring different leadership styles, and collaborating. I have also witnessed how visibility (visibility to ourselves, to understand who we are, and visibility to others, to let the world know we exist) helps to open up opportunities. The good news is that the beliefs we have about ourselves are just that – beliefs – and these beliefs can be changed.

My visibility to others has also increased notably in relation to my involvement in Homeward Bound and my recent award of the Queensland Women in STEM prize. This Australian annual prize, awarded by the Minister for Environment and Science, Leeanne Enoch and Acting Chief Scientist Dr Christine Williams, aims to celebrate the achievements of women who are making a difference in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. As a result, I have been contacted by fascinating people from various fields of work, from researchers and teachers to entrepreneurs, start-ups, and industries. All these connections have broadened my approach to food security and global change and helped me shape my research vision, purpose, and values.

When we were in Antarctica, our story reached 750 million people. Why? Because, and may we never forget, the world believes in us – ‘us’ in its broadest sense: humans, scientists, women, etc. – in our skill, compassion, and capability. While we are facing alarming global social, economic, and environmental challenges, I believe that the many collaborations that embrace diversity of knowledge, skills, processes, and leadership styles that are currently emerging all around the world, will help us get closer to our development goals.

Homeward Bound is a 10-year long initiative. Find out more about the program and how to apply here: http://homewardboundprojects.com.au

Follow my journey: –

Nov 21, 2017 | Alumni, Poverty & Equity, Young Scientists

By Nemi Vora, participant of the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) 2017 and PhD student at the University of Pittsburgh.

“Was it worth the flight?” asked my fellow alumna of the YSSP Karen Umansky, at the end of our first day of attending the World Science Forum in Jordan. The total journey from the USA to Jordan had taken 20 hours, layovers included. She was well aware of my travel anxiety, fear of immigration officials (an Indian passport doesn’t always make things easy), and fear of traveling alone on a militarized Dead Sea road at night (you can see the west bank on the other side). I had spammed her every day about it.

The IIASA delegation at the World Science Forum © IIASA

I didn’t have an answer; the panels I attended did not focus on anything new. We were all aware of issues: digitization without destruction, women in science, support for emerging scientists, meeting the sustainable development goals, and so on. However, every conference has a different key to unlock its potential and Jan Marco Müller, head of the IIASA directorate office and another recipient of my daily email spam, informed me that it was not the panels, but the corridor conversations that mattered here.

I soon found out that it was not just the corridors, but even the brief conversations in shuttles where the conference happened. I met a program manager for the US National Science Foundation who told me about research work on the food-energy-water nexus that they funded for the Nile, an area similar to my thesis. I met a regional director of UNESCO and a science minister from Colombia, who together set up new Africa-Latin America project partnerships during the shuttle ride.

One important part of each conversation was the significance of the place I was in, something I had previously missed completely. The ability of this small country, surrounded by conflict zones on each side, to arrange for such a large gathering of this kind, bringing together opponents and allies alike, and to take a stand for enabling peace through science, was remarkable.

True, the issues were not new, but the context was much more specific to the needs of a conflict-ridden world. For instance, discussing how to provide access to digital resources such as open data for policymaking or scientific journals for all the countries, promoting the achievements of Arab women scientists and those of the other developing regions amidst cultural and economic hardships, and fostering innovation in emerging scholars in the developing world where lack of resources was part of academic life.

Jordan also showcased the recently established SESAME facility: the Middle East’s first international science research center, a joint venture of a group of middle eastern countries, otherwise engaged in political conflicts. IIASA was representing a unique position here: originally founded as the bridge between East-West scientific collaboration during the Cold War, it served as an example, along with the fledgling SESAME, that geo-political boundaries did not hinder science and that such projects could be successful. Despite political tensions in individual countries, and having a passport that would not allow you to visit your colleague’s country, you could still work side-by side—a feat that SESAME scientists achieve every day.

As YSSPers, our goal was to talk about the benefits of global mentorship and how that could be leveraged to address the uneven distribution of resources. All of us came from different backgrounds: there was An Ha Truong from Vietnam, an energy economist studying optimization of biomass for coal power plants, there was Karen, the social scientist from Israel, studying emerging neo-Nazism in Europe, and then there was me—representing the USA and India as an environmental engineer.

Our co-panelists from the Berkeley Global Science Institute, also of diverse backgrounds, were engaged in setting up labs across the world, providing resources and mentorship to graduate students. While we had a lively session discussing our personal experiences, it wasn’t what we had to say but the session questions that struck a chord with us. The presence of conflicts add another layer of complexity to the already murky path of academia: how do you keep young scholars motivated to stay in the lab and work in a country threatened by war? How do you compete in cutting-edge science research when resources are scarce? How do you engage in public-private partnerships when your work may be more theoretical than applied?

The YSSPers taking part in a panel © IIASA

We need to collaborate more, provide access to the data and codes we use to carry out reproducible research, attempt to publish in open access platforms whenever feasible, and support our fellow scientists irrespective of their location or positions. This way, we would inch closer to solving some of these issues. Six months ago at IIASA, the HRH Sumaya bint El Hassan, co-chair of the World Science Forum, had asked me, “How do you eat an elephant?” Being a vegetarian, I couldn’t imagine ever eating one and I very naively told her so. On my way back from Jordan, with another long journey ahead of me, I realized the significance of her words: you eat it little by little.

Follow Nemi on twitter: @NemiVora

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.