Apr 2, 2020 | COVID19, Data and Methods, Finland, Health, Sustainable Development, Systems Analysis

By Leena Ilmola-Sheppard, senior researcher in the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program.

Leena Ilmola-Sheppard discusses the value of employing novel research methods aimed at producing fast results to inform policies that address immediate problems like the current COVID-19 pandemic.

© Alberto Mihai | Dreamstime.com

As researchers, the majority of our work – even if it is applied research – requires deep insight and plenty of reading and writing, which sometimes takes years. When we initiate a new method development project, for example, we never know if it will eventually prove to be useful in real life, except on very rare occasions when we are willing to step out of our academic comfort zones and explore if we are able to address the challenges that decision makers are faced with right now.

I would like to encourage my colleagues and our network to try and answer the call when decision makers ask for our help. It however requires courage to produce fast results with no time for peer review, to explore the limits of our knowledge and capabilities of our tools, and to run the risk of failure.

I share two examples with you in this blog. The first one describes a situation that played out years ago, while the second one is happening today.

When the first signs of a potential refugee crisis became visible late in 2014, the Finnish Prime Minister’s Office contacted the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program (ASA) and asked whether we could produce an analysis for them. The ASA team had an idea to develop a new method for qualitative systems analysis based on an application of causal-loop-diagrams and we decided to test the approach with an expert team of 14 people from different Finnish ministries. I have to admit that the process was not exactly the best example of rigorous science, but it was able to produce results in only eight weeks.

“Experts that participated in the process from the government side accepted that the process was a pilot and exploratory in nature. In the end, the group was however able to develop a shared language for the different aspects of the refugee situation in Finland. The method produced comprised a shared understanding of the events and their interdependencies and we were able to assess the systemic impact of different policies, including unintended consequences. That was a lot in that situation,” said Sari Löytökorpi, Secretary General and Chief Specialist of the Finnish Prime Minister’s Office when reflecting on that experience recently.

The second case I want to describe here is the current coronavirus pandemic. The COVID-19 virus reached Finland at the end of January when a Chinese tourist was diagnosed. The first fatality in Finland was recorded on 20 March. This time, the challenge we are presented with is to look beyond the pandemic. The two research questions presented to us by the Prime Minister’s Office and the Ministry of Economic Affairs are: ‘How can the resilience of the national economy be enhanced in this situation?’ and secondly ‘What will the world look like after the pandemic?’

Pekka Lindroos, Director of Foresight and Policy Planning in the Finnish Ministry of Economic Affairs is confident, “We know that the pandemic will have a huge impact on the economy. The global outcome of current national policy measures is a major unknown and traditional economic analysis is not able to cover the dynamics of the numerous dimensions of the rupture. That is why we are exploring a combination of novel qualitative analysis and foresight methods with researchers in the IIASA ASA Program.”

I have been working on the implementation of the systems perspective to the coronavirus situation with a few close colleagues around the world who are experts in resilience and risk. We were able to deliver the first report on Friday, 27 March. Among other things, it emphasized the role of social capital and society’s resilience. A more detailed report is currently in production.

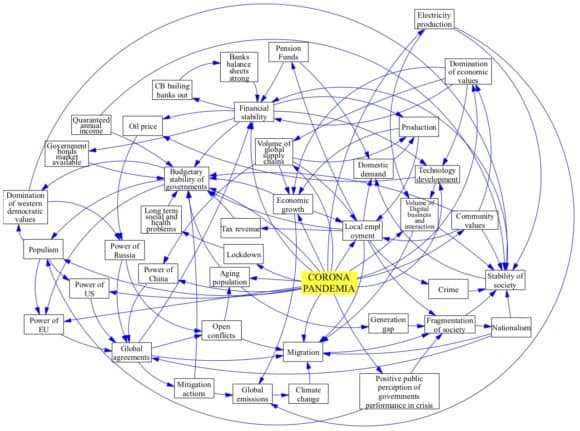

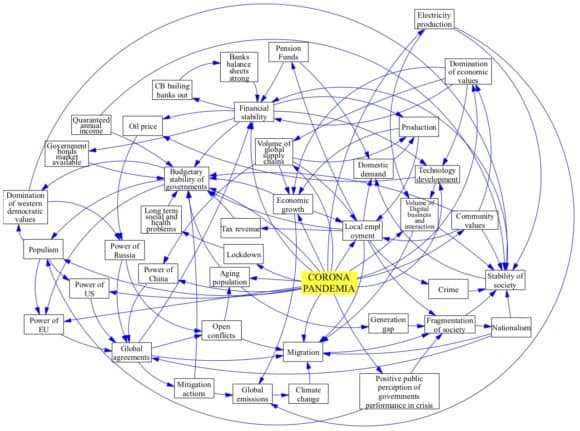

A simple systems map (causal loop diagram) representing a preliminary understanding of the world after COVID-19 from a one country perspective.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 21, 2019 | Alumni, IIASA Network, Netherlands, Systems Analysis

Leen Hordijk has served in the capacity of project leader, Council member, and director of IIASA. He is currently professor emeritus at Wageningen University and special adviser to the Competence Centre on Modeling at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC). He was recently interviewed by IIASA Network and Alumni officer, Monika Bauer.

Leen Hordijk at IIASA in 2006.

In 2007, you wrote an Options article on what systems analysis is in which you stated that systems analysis at IIASA is making an important—even essential—contribution to solving some of the world’s most complex problems. Is the role of systems analysis even more important today, and if so why?

In today’s world, it is indeed more important. First and foremost, the world is more complex than it was 20 years ago. Internet, social media, and the accessibility of transport options make the world more connected and thus more complex. Systems analysis can assist in disentangling the complexities and in trying to quantify where possible. Science is frequently under attack by interest groups, climate change deniers, and even some governments. It is therefore even more important to have an international, multidisciplinary, and multi-cultural institute like IIASA to bring scientific results to policymakers and society. Impartiality and knowledgeability are in the institute’s genes. The world notices this in scientific contributions by IIASA to policy debates in energy, biodiversity, climate change, disaster management, air quality, aging population issues, water management, and technology development.

In my personal development, IIASA has played a key role since my first visit in 1979 when I attended a regional economics conference. “IIASA gets into your blood”, as one of our sons said when I was thinking about applying for the IIASA directorship back in 2001. That is so true for many alumni.

What are your reflections on your time as IIASA Director General?

When I arrived as director in 2002, the challenge was twofold. First, I had to deal with financial issues, as two major members of IIASA had not lived up to their commitments, while expenditures had not been reduced. Second, some ten years after the end of the Cold War, the IIASA membership structure had not changed. The first problem was solved through a thorough 25% expenditure reduction plan and a re-engagement of said members. IIASA staff realized that cuts were necessary, and they were very engaged in finding solutions. The re-engagement of member countries went quickly because of the involvement of Austrian government officials, in particular Raoul Kneucker. The second issue took more time: expanding membership for IIASA to become a global institute rather than an East-West one. With China already on board when I arrived, we expanded membership with Egypt, India, Pakistan, South Africa, and the Republic of Korea.

In terms of content and scientific quality, I was very happy to find an excellent staff. What surprised me was that the number of social scientists (including economists) was higher than I had expected, and the total sum of external financing was quite low. In the following years, most programs became very successful at acquiring projects funded by the European Research Council and various Directorates-General of the European Commission.

Today, IIASA is a major player in terms of providing impartial scientific input in the analysis of many global challenges, such as energy, air quality and climate change, sustainable development, disaster risks, ecosystem services, demography, and technological transitions. IIASA is often a leading institute in signaling global trends and changes and, very importantly, uses its broad systems analytic and modeling capacity to quantify such changes and bring the results to policy fora.

In your opinion, how has the Dutch community benefited from the IIASA network?

It is always very hard to point at such benefits, because more often than not, they cannot be linked to single causes. That aside, I think that the Netherlands’ strength in systems analysis for environment, climate, and energy can, for a substantial part, be linked to leading scientists who spent time at IIASA and/or are active participants in IIASA networks. Last year I came across a nice example when I had a temporary assignment as chief scientist at PBL, the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. In that year, PBL was heavily involved in analyzing a draft national climate agreement for the Dutch government. I met two key scientists in that team who I knew as Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participants during my time as director of IIASA. It was very exciting to notice how they had grown since their time as YSSPers and became essential in the PBL team.

Being part of global scientific networks, gaining experience in advanced interdisciplinary work, and, last but not least, the YSSP, are specific benefits all member countries receive from being a part of IIASA. IIASA was not founded for the benefit of single countries – it is the global good that the institute tries to understand and serve.

I have also personally benefited from being a part of the IIASA network. When I left IIASA in May 2008, I became director of the Institute for Environment and Sustainability of the JRC in Ispra, Italy. IIASA and the JRC have become close collaborators in various fields of research.

More updates from IIASA alumni or information on the IIASA network may be found here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 1, 2019 | Alumni, IIASA Network, Systems Analysis

By Christoph E. Mandl, IIASA alumnus and Senior Lecturer at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna

Apprehensive about ever growing crises of corporate and political governance, I wrote a book titled, Managing complexity in social systems: Leverage points for policy and strategy, that addresses these crises and appropriate actions from a complex systems, system dynamics, and systems thinking perspective. The premise of the book is that more and more policies and strategies tend to fail and it is based on my personal experiences and the stories of many policymakers.

© Peshkova | Dreamstime

In her disconcerting booklet, The collapse of Western civilization: A view from the future Naomi Oreskes stated: “Analysts agree that the people of Western civilizations knew what was happening to them but were unable to stop it. Indeed, the most startling aspect of this collapse is just how much these people knew, and how unable they were to act upon what they knew.”

So, what can be done about this? How can the complexity of modern societies be managed? Naturally, answers to these questions are anything but trivial. Insights from complexity science, system dynamics, system theory, and systems thinking may not give a full answer but could perhaps point us in the right direction.

In writing my book aimed at closing these societal knowing-doing gaps, four IIASA alumni shaped and influenced my thinking:

The first was Thomas Schelling, who was key for me in showing how, in the context of segregation, a social system’s macro-behavior emerges that is quite different to the micro-motives of the individuals.

Brian Arthur’s book, Increasing returns and path dependence in the economy, revealed to me a totally new perspective on the dynamics of social systems where disequilibrium is not only possible, but normal.

Through John Sterman’s article Bathtub dynamics: Initial results of a systems thinking inventory, I understood how important the distinction between stocks and flows is for decision making in dynamic environments.

Lastly, when I first came across Donella Meadows’ article, Places to intervene in a system, its impact on me was profound. In my view, it was the first publication that addressed decision making from a strictly dynamic point of view. This article and her publication Chicken Little, Cassandra, and the real wolf, forever changed and inspired my thinking about what it means to manage and to make decisions.

Without the insights of these four outstanding IIASA alumni, my book would never have been written. Thank you, IIASA, for bringing them all to Laxenburg!

More updates from IIASA alumni or information on the IIASA network may be found here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 26, 2019 | Environment, Systems Analysis, Young Scientists

By Luiza Toledo, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2019

2019 YSSP participant Roope Kaaronen investigates how changes in the urban environment affect people’s behavior and whether they will find it easy to engage in sustainable behavior in different environments.

Technological and industrial advances in many sectors have made our lives easier, but they have also contributed to a less sustainable way of life. From the industrial revolution to the present day, CO2 emissions have increased by 40% and about 95% of this increase can be attributed to human actions. We can therefore say that our actions shape the environment we live in. But how does the environment we live in in turn shape our attitudes and behavior?

Apart from the vast amount of information available to us and an increasing awareness of more sustainable consumption, our society still has a growing carbon footprint, which means that attitudes around sustainability are not really translating into behavior. There is a gap between having environmental knowledge and environmental awareness, and displaying pro-environmental behavior. Apparently, the answer to translating attitudes into behavior could have more to do with design than awareness.

Roope Kaaronen, YSSP participant. © Kaaronen

Roope Kaaronen, a member of this year’s IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) cohort, has made it his goal to study behavior change and the adoption of sustainable habits. His project investigates how changes in the urban environment will affect people’s behavior and whether people will find it easy to engage in sustainable behavior in different environments. He is looking at how pro-environmental behavior patterns emerge from processes of social learning (such as teaching and imitation), habituation, and niche construction (a process where agents shape the environment they act in).

“I am particularly interested in how the physical environment shapes our behaviors, because people often assume that they have a pro-environmental attitude or values, and that this automatically translates into sustainable behavior. Research however shows that this is often not the case. So actually, the physical environment is more important in determining how we behave than we think,” he explains.

For instance, suppose that you would like to start recycling more but your city doesn’t have a proper selective waste collection system. Because the infrastructure needed to promote pro-environmental behavior is missing, this can lead to feelings of frustration and hopelessness, which could in turn cause people to give up on even trying to engage in the behaviors that could lead to more sustainable outcomes.

Kaaronen uses agent-based modeling in his research to model the cultural evolution of sustainable behavior patterns. The idea is to study how opportunities for action can have self-reinforcing effects on behavior. He included agents who move on a “landscape of affordances” in his model, and these agents are connected to each other in a social network. In this context, the term “agents” represents individuals or groups in society.

Social psychology describes pro-environmental behavior as conscious actions made by an individual to minimize the negative impact of human activities on the environment. For Kaaronen, this means that we can only achieve sustainable goals if we change our behaviors or habits very quickly.

“I think that it’s not realistic to expect that technology will solve all our problems. We will have to start behaving differently,” he says.

Unfortunately, people very often assume that individuals’ actions don’t have as much impact as collective actions, leading them to postpone their own pro-environmental behaviors. There have been a lot of discussion in the media around whether one person’s attitude could have an impact on the environment, in other words, should the focus be on each individual making changes in the way they live, or should the focus be on whole systems changing. To Kaaronen, these two approaches are connected.

“Systems emerge from individuals and their collective interactions. As we are social animals, our actions are inevitably copied and imitated by other people. This means that a person who has a lot of influence will have many people copying them. In other words, whenever we talk about private environmental behavior, such as recycling or using public transport rather than driving a car, we tend to think that this is just our personal behavior, but of course, our choices form part of a much bigger system,” says Kaaronen.

Woman helps clean the beach of garbage. © Freemanhan2011 | Dreamstime.com

We should be aware that we need politicians to make our pro-environmental choices as easy as possible. As individuals, we have responsibilities because we are part of the social system, but it is up to the political system to encourage this kind of behavior on a larger scale.

In 2007, the Danish government developed a strategy that prioritized bicycling as method of transport in Copenhagen. Since then, the city has seen a rapid increase in the number of people cycling, showing that affordance is important to promoting behavior change. Kaaronen’s model is able to reproduce patterns of behavior change, such as the case of Copenhagen.

“I think in terms of policy, what I am doing is quite applicable in urban design. What I am trying to show is that if we make sustainable behavior easy and lucrative, this can lead to long lasting and self-reinforcing effects on the emergence of sustainable cultures,” he comments.

The advent of social media has made it easy to influence people’s attitudes and behavior. The model that Kaaronen is using also illustrates how behavior change can spread through tightly knit social networks, and how social learning in networks can have self-reinforcing effects on behavior change. He says that we should use this tool to spread awareness about sustainable habits and initiate cultural evolution towards sustainable societies. In terms of behavior, living by example is very important, since it is necessary to show that living a sustainable life is both possible and enjoyable. Kaaronen himself lives this philosophy as he doesn’t drive and tries not to eat meat. He also stopped flying two years ago.

“I am just travelling on the ground right now. It is part of a campaign in the academic environment called #FlyingLess. Buses and trains can take you to interesting places, but it of course takes up a lot of time and I realize that not everyone can do this because they live in places that aren’t well connected.”

We are so used to unsustainable forms of behavior like constantly driving, flying, and consuming meat, but the world needs to realize that this way of living cannot last forever. It is unsustainable. Even though it may appear challenging to change our behavior, Kaaronen’s research offers hope to keep believing that it is possible to change our unsustainable behavior and achieve a sustainable society and environment.

“I think it is important to show that these things are actually possible. We can reach a tipping point towards sustainable systems if enough people just start practicing what they preach,” he concludes.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 6, 2019 | Data and Methods, Ecosystems, Systems Analysis, Young Scientists

By Davit Stepanyan, PhD candidate and research associate at Humboldt University of Berlin, International Agricultural Trade and Development Group and 2019 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) Award Finalist.

Participating in the YSSP at IIASA was the biggest boost to my scientific career and has shifted my research to a whole new level. IIASA provides a perfect research environment, especially for young researchers who are at the beginning of their career paths and helps to shape and integrate their scientific ideas and discoveries into the global research community. Being surrounded by leading scientists in the field of systems analysis who were open to discuss my ideas and who encouraged me to look at my own research from different angles was the most important push during my PhD studies. Having the work I did at IIASA recognized with an Honorable Mention in the 2019 YSSP Awards has motivated me to continue digging deeper into the world of systems analysis and to pursue new challenges.

© Davit Stepanyan

Although my background is in economics, mathematics has always been my passion. When I started my PhD studies, I decided to combine these two disciplines by taking on the challenge of developing an efficient method of quantifying uncertainties in large-scale economic simulation models, and so drastically reduce the need and cost of big data computers and data management.

The discourse on uncertainty has always been central to many fields of science from cosmology to economics. In our daily lives when making decisions we also consider uncertainty, even if subconsciously: We will often ask ourselves questions like “What if…?”, “What is the chance of…?” etc. These questions and their answers are also crucial to systems analysis since the final goal is to represent our objectives in models as close to reality as possible.

I applied for the YSSP during my third year of PhD research. I had reached the stage where I had developed the theoretical framework for my method, and it was the time to test it on well-established large-scale simulation models. The IIASA Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM), is a simulation model with global coverage: It is the perfect example of a large-scale simulation model that has faced difficulties applying burdensome uncertainty quantification techniques (e.g. Monte Carlo or quasi-Monte Carlo).

The results from GLOBIOM have been very successful; my proposed method was able to produce high-quality results using only about 4% of the computer and data storage capacities of the above-mentioned existing methods. Since my stay at IIASA, I have successfully applied my proposed method to two other large-scale simulation models. These results are in the process of becoming a scientific publication and hopefully will benefit many other users of large-scale simulation models.

Looking forward, despite computer capacities developing at high speed, in a time of ‘big data’ we can anticipate that simulation models will grow in size and scope to such an extent that more efficient methods will be required.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 24, 2019 | Data and Methods, Systems Analysis, Women in Science

By Sibel Eker, IIASA postdoctoral research scholar

Ceci n’est pas une pipe – This is not a pipe © Jaka Vukotič | Dreamstime.com

Quantitative models are an important part of environmental and economic research and policymaking. For instance, IIASA models such as GLOBIOM and GAINS have long assisted the European Commission in impact assessment and policy analysis2; and the energy policies in the US have long been guided by a national energy systems model (NEMS)3.

Despite such successful modelling applications, model criticisms often make the headlines. Either in scientific literature or in popular media, some critiques highlight that models are used as if they are precise predictors and that they don’t deal with uncertainties adequately4,5,6, whereas others accuse models of not accurately replicating reality7. Still more criticize models for extrapolating historical data as if it is a good estimate of the future8, and for their limited scopes that omit relevant and important processes9,10.

Validation is the modeling step employed to deal with such criticism and to ensure that a model is credible. However, validation means different things in different modelling fields, to different practitioners and to different decision makers. Some consider validity as an accurate representation of reality, based either on the processes included in the model scope or on the match between the model output and empirical data. According to others, an accurate representation is impossible; therefore, a model’s validity depends on how useful it is to understand the complexity and to test different assumptions.

Given this variety of views, we conducted a text-mining analysis on a large body of academic literature to understand the prevalent views and approaches in the model validation practice. We then complemented this analysis with an online survey among modeling practitioners. The purpose of the survey was to investigate the practitioners’ perspectives, and how it depends on background factors.

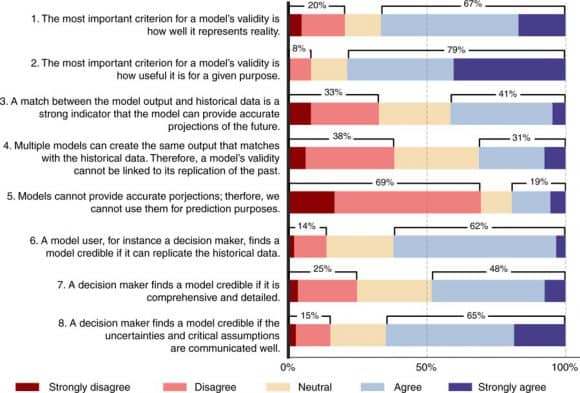

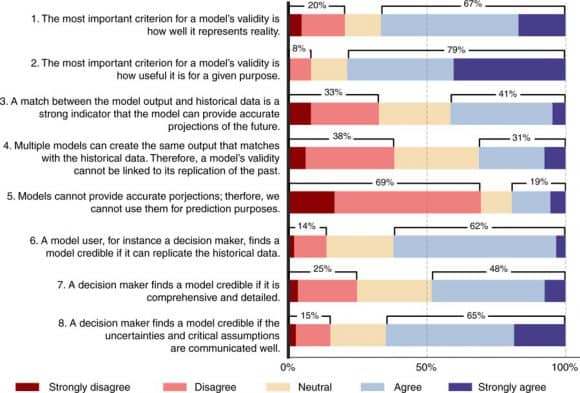

According to our results, published recently in Eker et al. (2018)1, data and prediction are the most prevalent themes in the model validation literature in all main areas of sustainability science such as energy, hydrology and ecosystems. As Figure 1 below shows, the largest fraction of practitioners (41%) think that a match between the past data and model output is a strong indicator of a model’s predictive power (Question 3). Around one third of the respondents disagree that a model is valid if it replicates the past since multiple models can achieve this, while another one third agree (Question 4). A large majority (69%) disagrees with Question 5, that models cannot provide accurate projects, implying that they support using models for prediction purposes. Overall, there is no strong consensus among the practitioners about the role of historical data in model validation. Still, objections to relying on data-oriented validation have not been widely reflected in practice.

Figure 1: Survey responses to the key issues in model validation. Source: Eker et al. (2018)

According to most practitioners who participated in the survey, decision-makers find a model credible if it replicates the historical data (Question 6), and if the assumptions and uncertainties are communicated clearly (Question 8). Therefore, practitioners think that decision makers demand that models match historical data. They also acknowledge the calls for a clear communication of uncertainties and assumptions, which is increasingly considered as best-practice in modeling.

One intriguing finding is that the acknowledgement of uncertainties and assumptions depends on experience level. The practitioners with a very low experience level (0-2 years) or with very long experience (more than 10 years) tend to agree more with the importance of clarifying uncertainties and assumptions. Could it be because a longer engagement in modeling and a longer interaction with decision makers help to acknowledge the necessity of communicating uncertainties and assumptions? Would inexperienced modelers favor uncertainty communication due to their fresh training on the best-practice and their understanding of the methods to deal with uncertainty? Would the employment conditions of modelers play a role in this finding?

As a modeler by myself, I am surprised by the variety of views on validation and their differences from my prior view. With such findings and questions raised, I think this paper can provide model developers and users with reflections on and insights into their practice. It can also facilitate communication in the interface between modelling and decision-making, so that the two parties can elaborate on what makes their models valid and how it can contribute to decision-making.

Model validation is a heated topic that would inevitably stay discordant. Still, one consensus to reach is that a model is a representation of reality, not the reality itself, just like the disclaimer of René Magritte that his perfectly curved and brightly polished pipe is not a pipe.

References

- Eker S, Rovenskaya E, Obersteiner M, Langan S. Practice and perspectives in the validation of resource management models. Nature Communications 2018, 9(1): 5359. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-07811-9 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/15646/]

- EC. Modelling tools for EU analysis. 2019 [cited 16-01-2019]Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/analysis/models_en

- EIA. ANNUAL ENERGY OUTLOOK 2018: US Energy Information Administration; 2018. https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/info_nems_archive.php

- The Economist. In Plato’s cave. The Economist 2009 [cited]Available from: http://www.economist.com/node/12957753#print

- The Economist. Number-crunchers crunched: The uses and abuses of mathematical models. The Economist. 2010. http://www.economist.com/node/15474075

- Stirling A. Keep it complex. Nature 2010, 468(7327): 1029-1031. https://doi.org/10.1038/4681029a

- Nuccitelli D. Climate scientists just debunked deniers’ favorite argument. The Guardian. 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2017/jun/28/climate-scientists-just-debunked-deniers-favorite-argument

- Anscombe N. Models guiding climate policy are ‘dangerously optimistic’. The Guardian 2011 [cited]Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/feb/24/models-climate-policy-optimistic

- Jogalekar A. Climate change models fail to accurately simulate droughts. Scientific American 2013 [cited]Available from: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/the-curious-wavefunction/climate-change-models-fail-to-accurately-simulate-droughts/

- Kruger T, Geden O, Rayner S. Abandon hype in climate models. The Guardian. 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2016/apr/26/abandon-hype-in-climate-models

You must be logged in to post a comment.