Jan 13, 2022 | Austria, Climate Change, COVID19, Energy & Climate, Sustainable Development

By Thomas Schinko, IIASA Equity and Justice Research Group Leader in the Population and Just Societies Program

IIASA researcher Thomas Schinko discusses the visionless outcomes of the recent UN Climate Conference (COP26) in Glasgow and an Austrian project he is involved in, which aims to co-create courageous and positive visions for a low-carbon and climate resilient future.

© Kengmerry | Dreamstime.com

In December 2015, the international community agreed to limit global average temperature increase to “well below 2°C” above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to hold them to 1.5°C under a landmark agreement known as the Paris Climate Accord. At COP26, which many considered the real follow-up to Paris, nations were asked to present updated plans and procedures to deliver in Glasgow what Paris promised.

While this ambitious goal was not achieved with the Glasgow Climate Pact and many delegates speaking in the closing plenary expressed disappointment, COP26 President Alok Sharma said that at least it “charts a course for the world to deliver on the promises made in Paris”, and parties “have kept 1.5°C alive”. However, parties substantially differ in their views around whether COP26 actually kept the 1.5°C target within reach.

In the time between Paris and Glasgow, we have seen the climate crisis unfolding in almost all parts of the world, with record heatwaves, storms, heavy rains, floods, droughts, wildfires, rising sea levels, and melting glaciers, to name but a few. At the same time, and notwithstanding many nations’ existing mitigation pledges, global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are still on the rise, and despite the small temporary dent to the upward sloping curve induced by COVID-19 pandemic related impacts on the world economy, there is no turning point in sight. While more and more nations are setting net-zero targets towards the middle of the century – most recently India announced reaching net-zero at COP 26, although only by 2070 – there is still a lack of intermediate steps, concrete measures, and financing strategies around how to achieve those targets.

What we need to achieve climate neutrality by mid-century and thereby stand a decent chance of preventing the worst effects of the climate crisis, is an immediate and drastic U-turn in the global GHG emission trajectory, rather than slowly reaching a turning point. The cuts required per year to meet the projected emissions levels for 2°C and 1.5°C are now 2.7% and 7.6% respectively, from 2020 and per year on average. This in turn requires sudden and drastic climate action at different policy and governance levels, rather than some incremental policy and behavioral changes.

However, many policy- and decision makers, as well as other societal stakeholders, consider such radical change impossible. I am positive we have all heard many excuses for slow progress in climate action, including that people won’t tolerate any climate policy measures that would require a palpable change in their lifestyles, habits, and routines; or that there is no money after carrying our economies through the economic crisis induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Other favorites are that “there is no alternative to our growth-based economic model”; or “our industries cannot just change their business models from one day to another”.

Overall, such excuses are blatant manifestations of a more general observation: At the heart of political failure there is often a lack of imagination or vision. One might argue that the policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have shown that governments are able to actually govern, and people were ready to profoundly change their behaviors. However, the overarching policy narrative was suggesting that these changes are all temporary and that once the pandemic is under control, we will move back to the pre-crisis state. In the context of the climate crisis and other closely related grand global challenges such as the biodiversity crisis, a “back to the future” narrative is at least useless and in the worst case even counterproductive.

To operationalize the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal and the follow-up Glasgow Climate Pact, we need courageous forward-looking visions that go beyond technology scenarios by describing what a climate neutral and resilient society could look like in all its complex facets. Last minute interventions at COP26 to tone down the Pact’s wording on fossil fuels to “phasing down” unabated coal power and “phasing out” inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, have proven once more that international climate policymaking is a tough diplomatic struggle, but also that it still suffers from a chronic lack of imagination at all levels.

Also at the individual level, recent research has found that while citizens are alarmed by the climate crisis, few are willing to act proportionately as they lack a clear vision of what a low-carbon transformation actually means. If we are not able to develop courageous visions of low-carbon and climate resilient futures that generate broad societal buy-in, we will not be able to identify and implement radical and transformational climate actions that will catapult us onto the low-carbon trajectories that have been laid out by scientists for achieving the 1.5°C goal. Hence, these visions need to be co-created with all relevant societal stakeholders that have a legitimate claim in the low-carbon transformation of our societies.

In developing such joint visions, it is of the utmost importance to first understand and eventually negotiate between different imaginations of a livable future and perceptions of what constitutes fair outcomes of, and just process for this fundamental transformation our societies will have to undergo.

In Austria, as in many other countries, national and sub-national governments are announcing net-zero targets and starting to think about the strategies and measures needed to achieve those. With a transdisciplinary group of researchers, practitioners, and policy- and decision makers, we are developing a participatory process for Styria, one of Austria’s nine states, that aims to co-create courageous and positive visions for a low-carbon and climate resilient future with a representative group of about 50 people. The central building block of this process is a co-creation workshop called “climate modernity ̶ the 24-hour challenge”. This weekend workshop will not take up more than 24 hours in total of participants’ time and it not only aims to imagine visions, but also to back-cast from these visions what is required to achieve them.

With this process, we set out to support the development of a new, politically as well as societally feasible, climate, and energy strategy for Styria. The Klimaneuzeit website, which includes an online application form that allows for eventually inviting a representative group of participants, has just been launched. Stay tuned to find out more about our lessons learned in co-developing this visioning process and implementing this prototype in Austria.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 18, 2021 | Austria, Climate, Climate Change, Communication, Education, Health

By Thomas Schinko, Acting Research Group Leader, Equity and Justice Research Group

Thomas Schinko introduces an innovative and transdisciplinary peer-to-peer training program.

What do we want – climate justice! When do we want it – now! The recent emergence of youth-led, social climate movements like #FridaysForFuture (#FFF), the Sunrise Movement, and Extinction Rebellion has reemphasized that at the heart of many – if not all – grand global challenges of our time, lie aspects of social and environmental justice. With a novel peer-to-peer education format, embedded in a transdisciplinary research project, the Austrian climate change research community responds to the call that unites these otherwise diverse movements: “Listen to the Science!”

The climate crisis raises several issues of justice, which include (but are not limited to) the following dimensions: First, intragenerational climate justice addresses the fair distribution of costs and benefits associated with climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as the rectification of damage caused by residual climate change impacts between present generations. Second, intergenerational justice focuses on the distribution of benefits and costs from climate change between present and future generations. Third, procedural justice asks for fair processes, namely that institutions allow all interested and affected actors to advance their claims while co-creating a low-carbon future. Movements like #FFF maneuver at the intersection of those three forms of climate justice when calling on policy- and decision makers to urgently take climate action, since “there is no planet B”.

Along with the emergence of these youth-led social climate movements came an increasing demand for the expertise of scientists working in the fields of climate change and sustainability research. To support #FFF’s claims with the best available scientific evidence, a group of German, Austrian, and Swiss scientists came together in early 2019 as Scientists for Future. Since then, requests from students, teachers, and policy and decision makers for researchers to engage with the younger generation have soared, also in Austria. Individual researchers like me have not been able to respond to all these requests at the extent we would have liked to.

In this situation of high demand for scientific support, the Climate Change Center Austria (CCCA) and The Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research (BMBWF) have put their heads together and established a transdisciplinary research project – makingAchange. By engaging early on with our potential end users – Austrian school students – a truly transdisciplinary team of researchers as well as practitioners in youth participation and education (the association “Welt der Kinder”) has co-developed this novel peer-to-peer curriculum. The training program, which runs over a full school year, sets out to provide the students not only with solid scientific facts but also with soft skills that are needed for passing on this knowledge and for building up their own climate initiatives in their schools and municipalities. One of the key aims is to provide solid scientific support while not overburdening the younger generation who often tend to put too high demands on themselves.

Establishing scientific facts about climate change and offering scientific projections of future change on its own does not drive political and societal change. Truly inter- and transdisciplinary research is needed to support the complex transformation towards a sustainable society and the integration of novel, bottom-up civil society initiatives with top-down policy- and decision making. Engaging multiple actors with their alternative problem frames and aspirations for sustainable futures is now recognized as essential for effective governance processes, and ultimately for robust policy implementation.

Also, in the context of makingAchange it is not sufficient to communicate science to students in order to generate real-world impact in terms of leading our societies onto low-carbon development pathways. What is additionally needed, is to provide them with complementary personal and social skills for enhancing their perceived self-efficacy and response efficacy, which is crucial for eventually translating their knowledge into real climate action in their respective spheres of influence.

Recent insights from a medical health assessment of the COVID-19 related lockdowns on childhood mental health in the UK have shown that we are engaging in an already highly fragile environment. In addition, a recent representative study for Austria has shown that the pandemic is becoming a psychological burden. The study authors are particularly concerned about young people; more than half of young Austrians are already showing symptoms of depression. Hence, we must engage very carefully with the makingAchange students when discussing the drivers and potential impacts of the climate crises. Particularly since some of them are quite well informed about research, which has shown (by using a statistical approach) that our chances of achieving the 1.5 to 2°C target stipulated in the Paris Agreement are now probably lower than 5%. Another example of such alarming research insights comes in the form of a 2020 report by the World Meteorological Organization, which warns that there is a 24% chance that global average temperatures could already surpass the 1.5°C mark in the next five years.

Zoom group picture taken at the end of the second online makingAchange workshop for Austrian school students. Copyright: makingAchange

The first makingAchange activities and workshops have now taken place – due to the COVID-19 regulations in an online format, which added further complexity to this transdisciplinary research project. Nevertheless, we were able to discuss some of the hot topics that the young people were curious about, such as the natural science foundations of the climate crisis, climate justice, or a healthy and sustainable diet. At the same time, we provided our students with skills to further transmit this knowledge and to take climate action in their everyday live – such as a climate friendly Christmas celebration in 2020. The school student’s lively engagement in these sessions as well as the overall positive (anonymous) feedback has proven that we are on the right track.

The role of science is changing fast from “advisor” to “partner” in civil society, policymaking, and decision making. By doing so, scientists can play an important, active role in implementing the desperately needed social-ecological transformation of our society without becoming policy prescriptive. With the makingAchange project, we are actively engaging in this transformational process – currently only in Austria but with high ambitions to scale-out this novel peer-to-peer format to other geographical and cultural contexts.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Apr 29, 2020 | Austria, COVID19, Systems Analysis

By Tamás Krisztin, researcher in the IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Tamás Krisztin discusses the air travel restrictions instituted by governments across the globe and how effective they really are in terms of curbing the spread of COVID-19.

© Potowizard | Dreamstime.com

Many Western countries are reaching, or have reached, the peak of COVID-19 infections, and policymakers are increasingly turning their attention to the next critical question: how to lift lockdown restrictions responsibly, while at the same time making sure that trade and travel can be restored to as close to “normal” as possible? Our research indicates that stoppage of airline traffic and border closures, which were some of the first modes of transport to be restricted, should also be some of the last to be restored because of their critical role in spreading infections.

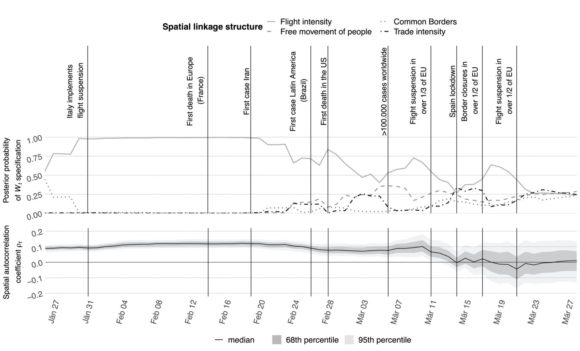

Governments began to restrict airline traffic at the end of January this year, and by 21 March, over half of the EU had implemented flight suspensions. Our research confirms that this was a timely and necessary step. In the early stages of the pandemic, international flight linkages were actually the main transmission channel for the virus. In fact, flight connections proved to be an even more accurate predictor of infection spread between two countries than the presence of common land borders or trade connections. As country after country enacted travel bans, our research also shows a corresponding decrease in cross-country spillovers of the virus.

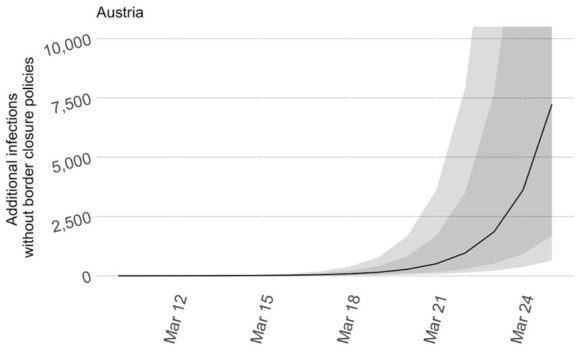

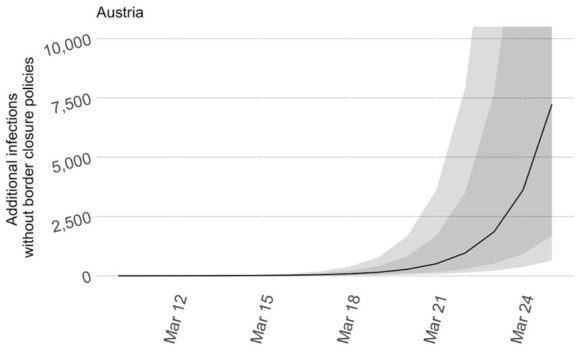

In Austria, for instance, our model demonstrates that if the shutdown of cross border traffic (flight connections and car border crossings) had been delayed by only 16 days, (25 March instead of 10 March), about 7,200 additional people would have been infected (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Additional infections in Austria without border closures (Note: Shaded areas correspond to the 68th and 90th quantiles, respectively).

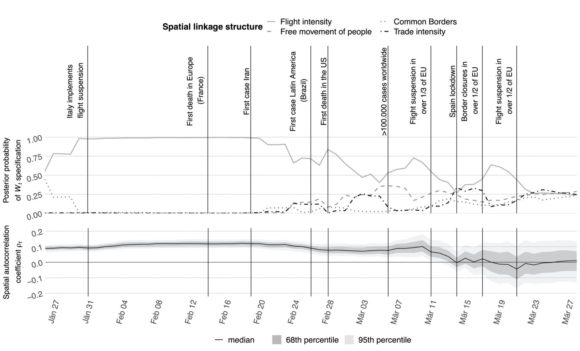

Additionally, our modeling shows the increased importance of flight connections over the initial period of the crisis, as seen in Figure 2. The top panel visualizes the relative importance of connectivity measures and demonstrates that, particularly in the beginning phases of the pandemic, flight connections were of the highest importance. The bottom panel shows infection spread between countries. Around the middle of March, when most border closure policies were implemented, the line drops to zero, indicating that these measures significantly reduced cross-border infections.

Figure 2: Importance of connectivity (top panel) and spatial spillovers (bottom panel)

Given the importance of air travel as a means for transmission of COVID-19, it stands to reason that governments and policymakers will have to continue to restrict air travel to prevent a second wave of the virus. As some parts of the world begin slowly to lift restrictions and ease lockdowns, while others are only now beginning to near the peak of the pandemic, it is likely that air travel will continue to be severely limited to prevent cross-border spread.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Apr 15, 2020 | Austria, COVID19, Demography

By Erich Striessnig, researcher in the IIASA World Population Program

Erich Striessnig discusses the risks posed by the current COVID-19 pandemic and shares insights from his latest research around socioeconomic indicators related to the pandemic in Austria.

© Bennymarty | Dreamstime.com

Late last year, my IIASA colleague Raya Muttarak, Roman Hoffmann from the Vienna Institute of Demography/Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, and I were informed by the City of Vienna that our proposal to study “Climate, Health and Population” (CHAP) in the metropolitan area of Vienna had been granted funding for the 2020 period. Originally, we wanted to study what climate change and demographic change in the rapidly growing Austrian capital implies with regard to future vulnerability to extreme weather events. As the city is booming with economic activity and experiencing more tropical summer heat every year, the extent of the urban heat island increases as well, thus posing a steadily increasing risk to the city’s growing population, especially the elderly.

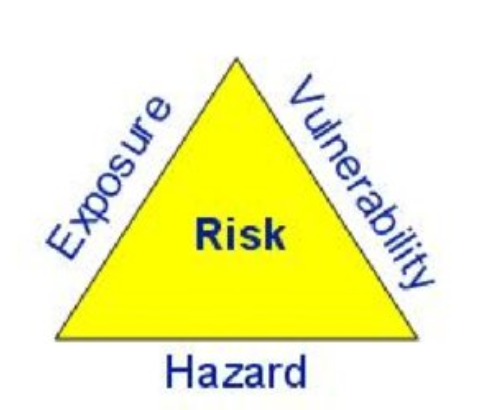

One conventional way of thinking about a population’s risk in the context of climate change is to decompose the risk and focus on its individual components. According to the famous “risk triangle” after Crichton, risk equals hazard times exposure times vulnerability. If any of the three can be taken out of the equation, the risk is reduced to zero … much like in the absence of sun, even the palest person can safely go outside without sunscreen! If, however, the hazard is there, people would be well advised to either not expose themselves to the sun or to reduce their vulnerability to skin damage and cancer by wearing sunscreen.

Now what does that have to do with our current predicament of a vast fraction of the world’s population being quarantined due to the outbreak of COVID-19? Well, as we and our CHAP colleagues were waiting for the meteorological data necessary for answering CHAP’s main research questions, we thought that we could focus on this much more imminent threat instead. In some way, the risk posed by COVID-19 can be viewed under the same lens as the above risk equation:

In terms of hazard, COVID-19 represents an unprecedented shock to social and economic systems and thus has a lot in common with climate-induced natural disasters. As humans are the carriers of the disease, the number of infected people in a local area can be considered as the hazard estimate. Meanwhile, by employing physical distancing (while remaining socially very active and helping, in particular, those around us that are in a more dire situation), we can lower exposure to that hazard a great deal and the risk can be reduced decisively. While under a business-as-usual scenario, our health system would soon find itself overwhelmed by an unbearable demand for health care, eventually having to give up lots of patients. The quarantine measures imposed in many countries serve to lower exposure and subsequently “flatten the curve”. So in order to reduce your own risk exposure and avoid increasing the risk for others, everyone who can afford to, please stay at home!

Likewise, we can to a certain extent work on lowering our vulnerability, both at the individual and at the societal level. Not everyone is equally vulnerable to the disease. As in the case of facing the challenges of climate change, populations faced with this pandemic are characterized by demographic differential vulnerability, expressed by the fact that the virus is more (but certainly not exclusively) lethal for older people, as well as those with preexisting health conditions and weakened immune systems. To reduce our individual vulnerability (in case we are exposed to the hazard), we can work on strengthening our immune systems.

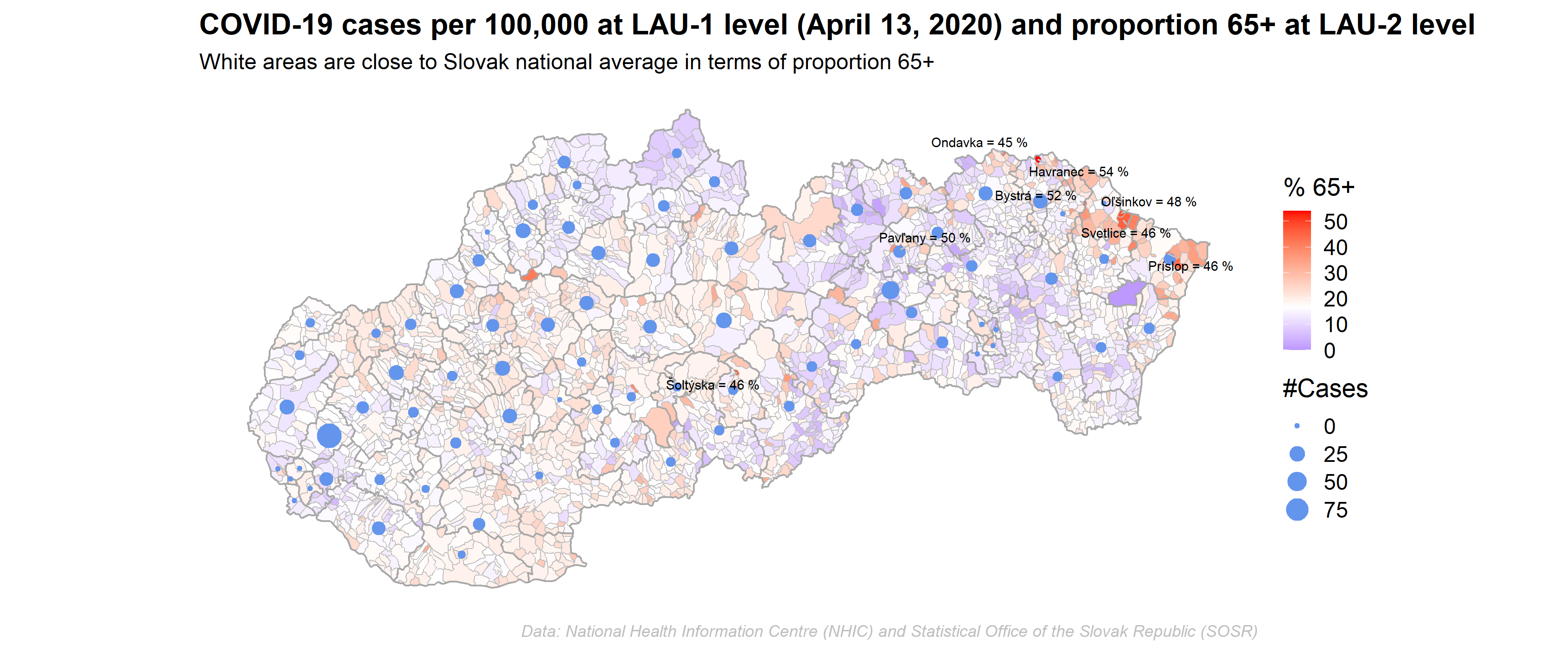

At the societal level, we can reduce risks by identifying those places where the disease outbreak might have the strongest impact. For this we need suitable indicators available with sufficient spatial granularity. The initial, pre-lockdown infection hotspots, were often places that are well connected, such as travel hubs and touristic areas. In some cases, though, these hotspots were created simply as the consequence of bad luck, in other words, because there was a local “super-spreader” or a social event that brought together a large number of people. Such situations can hardly be anticipated. What we might be able to anticipate, though, are those vulnerable geographical hotspots where, given the pre-existing burden of disease, as well as the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the people that live there, the pandemic might cause the most havoc.

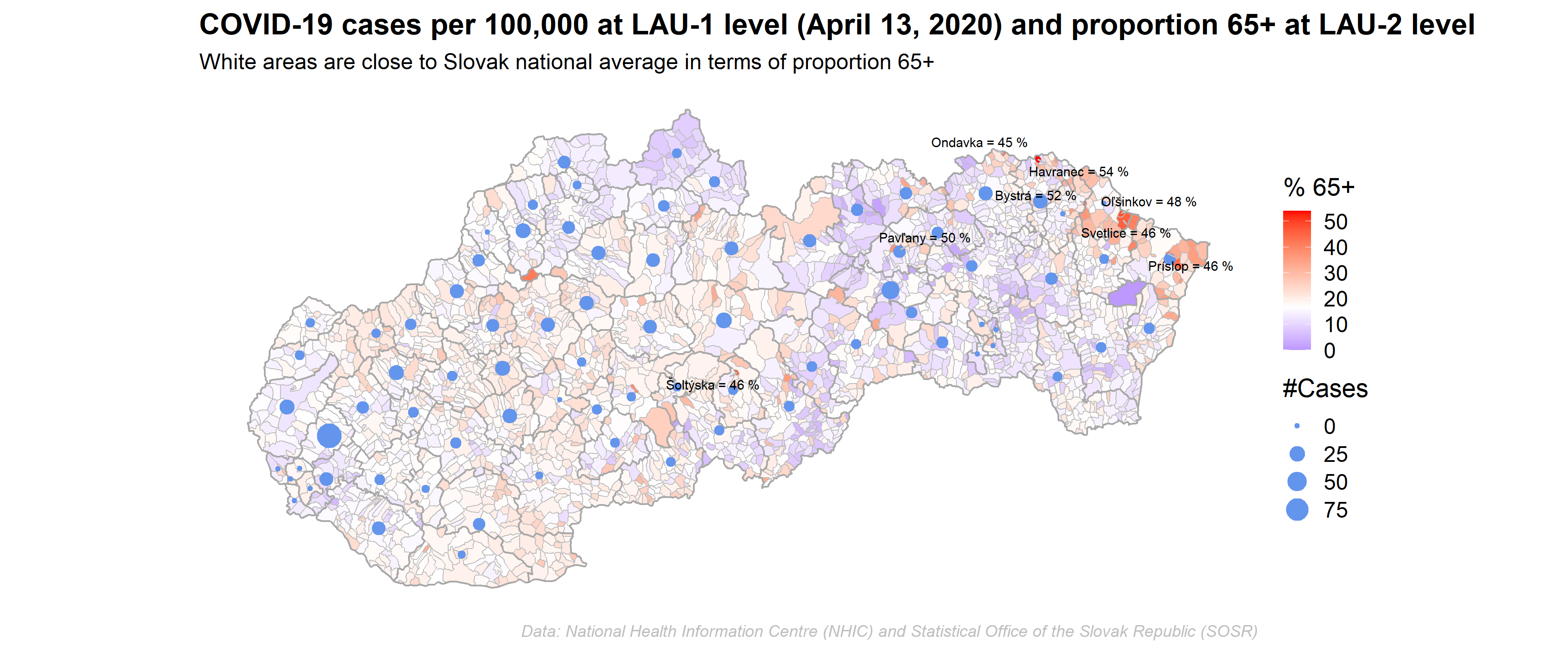

In line with the work by our IIASA colleague, Asjad Naqvi, we set out to map various indicators at the Austrian and Slovak municipal level (Slovak data courtesy of Michaela Potancokova from the IIASA World Population Program). Our indicators include things like the proportion of elderly population (>70+) or population density, but also the proportion of people with low socioeconomic status or a region’s connectedness in terms of the proportion of population commuting for work. These indicators can have varying importance in the short, medium, and long term — while mobility is no longer a big issue now that the population is in lockdown, socioeconomic characteristics, for example, may play a bigger role the longer the crisis lasts. While at the initial stages, Austrians with higher socioeconomic status were more likely to get infected due their mobility and larger social networks, the socioeconomic gradient might turn around eventually and those with lower social status might carry the brunt of the pandemic, as they are more likely to become unemployed and stay there for a longer period of time.

Our work to create a meaningful risk index from such vulnerability indicators is still in progress, but we aspire to pinpoint which areas are most likely going to need additional interventions, such as more testing or increased hospital capacities. This exercise will not only be useful at later stages of the pandemic, that is, when we slowly start moving back from the current quarantine situation (“The Hammer”) to gradual normalization (“The Dance”), but also when faced by other types of risks, such as from climatic hazards or economic shocks.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Dec 23, 2019 | Austria, Science and Policy

By Jan Marco Müller, IIASA Acting Chief Operations Officer

Jan Marco Müller shares his insights into the recent high-level forum in Vienna that brought together science advisors to ministers of foreign affairs from across the world and other experts in the practice, theory, and discussion of science diplomacy.

Established following an initiative by the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, IIASA can be considered a child of diplomacy for science. At the same time, the institute has always been one of the world’s premier vehicles of science for diplomacy, by using science to build bridges between nations including those with special relations. However, there is another dimension of science diplomacy which has gained traction in recent years: the support scientists can provide to diplomats and policymakers in the foreign policy domain – known as science in diplomacy.

© IIASA

As global challenges become more complex and interdependent and technological progress advances at an ever-increasing speed, the scientific-technical dimension of foreign policies has gained increasing attention. This is illustrated by four examples:

- Climate change impacts everybody on the planet, regardless of national borders.

- Many digital technologies escape national jurisdictions and so create tensions between nations: e.g. cryptocurrencies, deep fakes, and internet trolls.

- Trade agreements are often hampered by disagreements on technical standards, which themselves are influenced by societal values: people may still remember the discussions around chlorinated chicken in the US-EU trade negotiations a few years ago.

- National interests are increasingly entering international spaces, which in the past have been governed by science, such as the Arctic/Antarctic, the deep sea and outer space.

Ministries of foreign affairs and diplomatic services around the world are all confronted with similar issues and critically depend on advice provided by scientists.

With this in mind, on 25-26 November 2019 IIASA, together with the International Network for Government Science Advice (INGSA), the Austrian Federal Ministry of Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs, the Diplomatische Akademie Wien (Vienna School of International Studies), and the Natural History Museum Vienna, held the global meeting of the Foreign Ministries Science & Technology Advice Network (FMSTAN).

FMSTAN gathers science advisors to ministers of foreign affairs from around the planet, providing a platform for the exchange of information and best practices. IIASA hosted the first meeting of this network in October 2016, which has since grown significantly, with some 50 countries now participating in its biannual meetings.

The global meeting in November was organized back to back with the meetings of two other important networks in the science diplomacy arena: the Science Policy in Diplomacy and External Relations Network (SPIDER) – which is the science diplomacy branch of the International Network for Government Science Advice – and the Big Research Infrastructures for Diplomacy and Global Engagement through Science (BRIDGES) Network. BRIDGES was established a year ago following an initiative by my colleague Maurizio Bona at CERN and myself, with the aim of uniting the science diplomacy officers of all major international research infrastructures. In addition, a 3-day training course organized by the EU-funded project Using science for/in diplomacy for addressing global challenges (S4D4C) was arranged in parallel to achieve maximum synergies.

© IIASA (L-R): Jan Marco Müller and Jeffrey Sachs, Special Advisor to the UN Secretary-General on SDGs; Director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, NY.

The meetings were attended by around 100 science diplomats including the President-elect of the International Science Council Sir Peter Gluckman, the UN Advisor on the Sustainable Development Goals Jeffrey Sachs, the former Rector of the University for Peace of the UN Martin Lees, the S&T Advisor to the US Secretary of State Matt Chessen, the S&T Advisor to the Japanese Foreign Minister Teruo Kishi, the Science Diplomacy Advisor to the Mexican Foreign Minister José Ramón López Portillo, and the Chief Science Advisor in the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs Dirk-Jan Koch, to name just a few.

Six major topics were discussed:

- The role of science diplomacy in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

- The importance of science in international security policies

- The challenges for science diplomacy in the current geopolitical environment

- Technology Diplomacy

- The role of science in diplomatic curricula (and vice versa)

- Future challenges for science diplomacy and the role of systemic thinking in policymaking

The Vienna meeting offered a unique platform for all those who “speak science” in the diplomatic arena to exchange ideas and experiences, while fostering a common global agenda. For additional insights I recommend reading the piece “Science Diplomacy: A Pragmatic Perspective from the Inside” which aims at making the term science diplomacy more operational – all the four authors participated to the Vienna meeting.

Overall the event demonstrated once again the convening power of IIASA and the leadership of the institute in confirming Vienna as one of the global hubs for science diplomacy.

© Mahmood | BMEIA. FMSTAN/SPIDER members and participants of the S4D4C training course.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 12, 2019 | Austria, Communication, Demography, Women in Science

By Nadejda Komendantova, researcher in the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program

Nadejda Komendantova discusses how misinformation propagated by different communication mediums influence attitudes towards migrants in Austria and how the EU Horizon 2020 Co-Inform project is fostering critical thinking skills for a better-informed society.

© Skypixel | Dreamstime.com

Austria has been a country of immigration for decades, with the annual balance of immigration and emigration regularly showing a positive net migration rate. A significant share of the Austrian population are migrants (16%) or people with an immigrant background (23%). The migration crisis of 2015 saw Austria as the fourth largest receiver of asylum seekers in the EU, while in previous years, asylum seekers accounted for 19% of all migrants. Vienna has the highest share of migrants of all regions and cities in Austria, and over 96% of Viennese have contact with migrants in everyday life.

Scientific research shows that it is however not primarily these everyday situations that are influencing attitudes towards migrants, but rather the opinions and perceptions about them that have developed over the years. Perceptions towards migration are frequently based on a subjectively perceived collision of interests, and are socially constructed and influenced by factors such as socialization, awareness, and experience. Perceptions also define what is seen as improper behavior and are influenced by preconceived impressions of migrants. These preconceptions can be a result of information flow or of personal experience. If not addressed, these preconditions can form prejudices in the absence of further information.

The media plays an essential role in the formulation of these opinions and further research is necessary to evaluate the impact of emerging media such as social media and the internet, and their consequent impact on conflicting situations in the limited profit housing sector. Multifamily housing in particular, is getting more and more heterogeneous and the impacts of social media on perceptions of migrants are therefore strongest in this sector, where people with different backgrounds, values, needs, origins and traditions are living together and interacting on a daily basis. Perceptions of foreign characteristics are also frequently determined by general sentiments in the media, where misinformation plays a role. Misinformation has been around for a long time, but nowadays new technologies and social media facilitate its spread, thus increasing the potential for social conflicts.

Early in 2019, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) organized a workshop at the premises of the Ministry of Economy and Digitalization of the Austrian Republic as part of the EU Horizon 2020 *Co-Inform project. The focus of the event was to discuss the impact of misinformation on perceptions of migrants in the Austrian multifamily limited profit housing sector.

Nadejda Komendantova addressing stakeholders at the workshop.

We selected this topic for three reasons: First, this sector is a key pillar of the Austrian policy on socioeconomic development and political stability; and secondly, the sector constitutes 24% of the total housing stock and more than 30% of total new construction. In the third place, the sector caters for a high share of migrants. For example, in 2015 the leading Austrian limited profit housing company, Sozialbau, reported that the share of their residents with a migration background (foreign nationals or Austrian citizens born abroad) had reached 38%.

Several stakeholders, including housing sector policymakers, journalists, fact checkers, and citizens participated in the workshop. Among them were representatives from the Austrian Chamber of Labor, Austrian Limited Profit Housing (ALPH) companies “Neues Leben”, “Siedlungsgenossenschaft Neunkirchen”, “Heim”, “Wohnbauvereinigung für Privatangestellte”, the housing service of the municipality of Vienna, as well as the Austrian Association of Cities and Towns.

The workshop employed innovative methods to engage stakeholders in dialogue, including games based on word associations, participatory landscape mapping, as well as wish-lists for policymakers and interactive, online “fake news” games. In addition, the sessions included co-creation activities and the collection of stakeholders’ perceptions about misinformation, everyday practices to deal with misinformation, co-creation activities around challenges connected with misinformation, discussions about the needs to deal with misinformation, and possible solutions.

During discussions with workshop participants, we identified three major challenges connected with the spread of misinformation. These are the time and speed of reaction required; the type of misinformation and whether it affects someone personally or professionally; excitement about the news in terms of the low level of people’s willingness to read, as well as the difficulties around correcting information once it has been published. Many participants believed that they could control the spread of misinformation, especially if it concerns their professional area and spreads within their networking circles or among employees of their own organizations. Several participants suggested making use of statistical or other corrective measures such as artificial intelligence tools or fact checking software.

The major challenge is however to recognize misinformation and its source as quickly as possible. This requirement was perceived by many as a barrier to corrective measures, as participants mentioned that someone often has to be an expert to correct misinformation in many areas. Another challenge is that the more exciting the misinformation issue is, the faster it spreads. Making corrections might also be difficult as people might prefer emotional reach information to fact reach information, or pictures instead of text.

The expectations of policymakers, journalists, fact checkers, and citizens regarding the tools needed to deal with misinformation were different. The expectations of the policymakers were mainly connected with the creation of a reliable, trusted environment through the development and enforcement of regulations, stimulating a culture of critical thinking, and strengthening the capacities of statistical offices, in addition to making relevant statistical information available and understandable to everybody. Journalists and fact checkers’ expectations on the other hand, were mainly concerned with the development and availability of tools for the verification of information. The expectations of citizens were mainly connected with the role of decision makers, who they felt should provide them with credible sources of information on official websites and organize information campaigns among inhabitants about the challenges of misinformation and how to deal with it.

*Co-Inform is an EU Horizon 2020 project that aims to create tools for better-informed societies. The stakeholders will be co-creating these tools by participating in a series of workshops in Greece, Austria, and Sweden over the course of the next two years.

Adapted from a blog post originally published on the Co-Inform website.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.