Aug 23, 2018 | Ecosystems, Food

© Huating | Dreamstime.com

By Sandra Ortellado, 2018 Science Communication Fellow

China is the world’s biggest producer of both wild and farmed fish, yet the massive commercial fishing industry threatens thousands of years of tradition in ocean and freshwater fishing, as well as the livelihoods of coastal fishing communities.

In the past decade, some coastal ecosystems and environments have been destroyed and polluted in the process of industrialization. Millions of tons of fish are caught in Chinese territorial waters each year, such that overfishing of high value commercial species has led to a drastic decline of some native fisheries resources and species.

In response, the Chinese government released a five-year plan for protecting marine ecosystems and restoring wild capture fisheries. The plan promotes an agenda of “ecocivilization,” which emphasizes land–sea coordination, green development, and social–ecological balance.

It also calls for the introduction of additional output control measures, which directly limit the amount of fish coming out of a fishery. Existing input control measures restrict the intensity of gear used to catch fish, but they may not be sufficient to protect ecosystems.

Yi Huang, a member of this year’s YSSP cohort, has made it her goal to figure out how social ecological balance can be achieved even as fishery regulations shift towards increased input and output control.

Given the size of China’s fishing industry, large scale change requires the abstract concepts of “ecocivilization” to be translated into action, compliance, and enforcement at the local level. That means engaging with individual fishers, their communities, and their way of life, says Huang.

“If you want to control overfishing; the object of fishery management policy are fishers. So you need to understand human behavior to help you control overfishing.”

Huang’s project investigates how changes in fishery management will affect demographic, geographic, and socioeconomic trends in the Chinese fisher population. With the guidance of her supervisors, she’s also developing a bioeconomic model to analyze how output control measures like catch limits will affect ecological and socioeconomic conditions.

“I just want to figure out how to improve enforcement of this kind of policy and see if we can use it to solve the overfishing problem at the same time as giving those in the fishing industry a better life,” says Huang.

Current input control measures like licensing systems, vessel buyback programs, closed seasons, restricted areas, and fisher relocation programs are meant to discourage overfishing and transition towards more sustainable practices. Nevertheless, a decline in fishing vessels and restricted fishing seasons only resulted in an increase in total vessel engine power and large spikes in fishing activity just prior to the closed season.

According to the Chinese fishery statistical yearbook, the number of people employed in the fishing industry proliferated to 13.8 million in 2016, so in recent years the government has issued subsidies encouraging fishers not to fish in the off-season and to change vocation. Older fishers are hesitant to abandon an identity that has been passed down from generation to generation in their families. However, younger generations with access to higher education are lured by the prospect of more stable work outside of their fishing communities, which could really change the socioeconomic and demographic structure of coastal villages.

With the potential for increased output controls to incur drastic changes in coastal communities, it’s more important than ever that regulations are carefully designed with both socioeconomic and ecological factors in mind.

Huang hopes her research will help inform the process of policy development, which involves balancing the needs of both vulnerable fisheries labor and delicate ecosystems.

“When policymakers want to use output control in fishery management, maybe they will think more about the fisher or the socioeconomic aspect of the resolution,” says Huang.

“My research is at the national level, but when they design a regulation it’s at the local level, so my research can teach them how socioeconomic surveys at the local level can be used together with ecological research when they are preparing for regulations.”

Huang, who studied sociology at the Ocean University of China before starting as a PhD student in Marine Affairs at Xiamen University, has spent the past ten years researching coastal fishing communities. She has a deep fondness for the people she surveyed, who welcomed her into their homes and showed her the beauty of the environment that sustained them.

“I want to protect the ocean and the people that connect with it,” says Huang.

A sociological perspective has given Huang an eye for nuance and an appreciation for things that don’t turn out quite how you expect, as they often don’t in scientific research—especially when it attempts to explain human behavior.

For example, Huang says that although fishers may look like countryside people, they act very differently from farmers.

“The ocean has a lot more risk involved than planting on land,” explains Huang.

Because Chinese fishery regulation is currently focused almost exclusively on analyzing resources from an ecological perspective, she thinks sociology and anthropology research could add another revealing dimension to the approach.

“After doing surveys and analyzing the data, I will find maybe I’m wrong or maybe there is something more. That’s why I’m really interested in this kind of research,” says Huang.

As her research project develops, Huang says she’s grateful for the feedback of her supervisors and peers at IIASA, who both challenge and encourage her.

“Even when they have some critical comments on my research, I feel more confident that my research is meaningful, that they support me, and that they’re really interested in my research,” says Huang. “That’s what I can feel every day.”

Aug 10, 2018 | Demography, Education, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

© SasinTipchai | Shutterstock

By Sandra Ortellado, 2018 Science Communication Fellow

Science fiction depicts the future with a combination of fascination and fear. While artificial intelligence (AI) could take us beyond the limits of human error, dystopic scenes of world domination reveal our greatest fear: that humans are no match for machines, especially in the job market. But in the so-called fourth industrial revolution, often known as Industry 4.0, the line between future and fiction is a thread of reality.

Over the next 13 years, impending automation could force as many as 70 million workers in the US to find another way to make money. The role of technology is not only growing but also demanding a completely new way of thinking about the work we do and our impact on society because of it.

Rather than focusing on which jobs will disappear because of technological disruption, we could be identifying the most resilient tasks within jobs, says J. Luke Irwin, 2018 YSSP participant. His research in the IIASA World Population program uses a role- and task-based analysis to investigate professions that will be most resilient to technological disruption, with the hope of guiding workforce development policy and training programs.

“We are getting better and better at programming algorithms for machines to do things that we thought were really only in the realm of humans,” says Irwin. “The amount of disruption that’s going to happen to the work industry in the next ten years is really going to impact everyone.”

However, the fear and instability created by the potential disruption elicit chaos, and the response is hard to organize into constructive action. While the resources remain untapped, creativity and imagination are wasted on speculation instead of preparation.

“I couldn’t stand that there’s all this great evidence-based work out there about how we can improve people’s lives and no one is using it,” said Irwin, “I’m trying to align a lot of research and put it in a place where you can compare it and make it more useful and more transferable between the people who would be talking about this: educators, policymakers, employers, and anybody in the workforce.”

Using a German dataset with vocational training as well as time and task information, Irwin will break down jobs into the specific cognitive and physical skills involved and rank the durability of each skill.

Based on the identified jobs and skills, Irwin will go on to draw connections between labor-force capabilities and education policies. His goal is to scale the findings of the most resilient skills to the German labor system so that policymakers and academic institutions can retrain currently displaced workforces and reimagine the future of human work.

After all, while about half the duties workers currently handle could be automated, Mckinsey Global Institute suggests that less than 5% of occupations could be entirely taken over by computers. The future of predictable, repetitive, and purely quantitative work may be threatened, but automation could also open the door for occupations we can’t even imagine yet.

“I think people are amazing and that they have a lot more potential than we are currently capable of fulfilling,” says Irwin.

The World Economic Forum estimates that 65% of children today will end up in careers that don’t even exist yet. For now, an increasingly self-employed millennial generation works insecure, unprotected jobs. The new gig economy, characterized by temporary contracted positions, offers independence but also instability in the labor market.

Without stable work, people lose a sense of security, and that can be dangerous for a policy system that isn’t built to handle uncertainty.

The last industrial revolution caused two or three generations of people to be thrown into poverty and lose everything they had because it was all tied into their job, recalls Irwin.

“Everything gets bad when things are uncertain,” says Irwin, “And this is a very uncertain time. We need to have a better idea of what’s coming so we can actually make some change.”

Irwin, who earned his Master’s in Public Health in 2014, wants his work to have a preventative focus, trying to find those things that not enough people are talking about, but have the potential to make a huge impact on public well-being.

“Especially in the United States, where I live, we’re so tied up with our jobs—it seems like it’s over half our identity,” says Irwin, “We live to work in America.”

In a place like the US, where a job is not only a source of income, but also an identity and a health factor, Irwin’s research offers hope that technological disruption can foster opportunity instead of chaos.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 17, 2018 | Air Pollution, Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science, Young Scientists

© Stefano Barzellotti | Shutterstock

By Sandra Ortellado, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

When it comes to home cooking in rural India, health, behavior, and technology are essential ingredients.

Consider the government’s three-year campaign to reduce the damaging impacts of solid fuels traditionally used in rural households below the poverty line.

Initiated by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, a program called Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (Ujjwala) aims to safeguard the health of women and children by providing them access to a clean cooking fuel, liquid petroleum gas (LPG), so that they don’t have to compromise their health in smoky kitchens or wander in unsafe areas collecting firewood.

According to the World Health Organization, smoke inhaled by women and children from unclean fuel is equivalent to burning 400 cigarettes in an hour.

Nevertheless, an estimated 700 million people in India still rely on solid fuels and traditional cooking stoves in their homes. A subsidy of Rs. 1600 (US $23.47) and an interest free loan attempts to offset the discouraging cost of the upfront security deposit, the stove, and the first bottle of LPG, but this measure hasn’t been able to change habits on its own.

Why? Although the government has made an overwhelming effort to increase access, interconnected factors like cultural norms, economic trade-offs, and convenience require an in-depth analysis of human behavior and decision-making.

Abhishek Kar, 2018 YSSP participant ©IIASA

That’s why Abhishek Kar, a researcher in the IIASA Energy Program and a participant in the 2018 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), has designed a study to explore how rural households make choices about access and usage. Borrowing from behavior change and technology adoption theories, he wants to know whether low-cost access is enough incentive for Ujjwala beneficiaries to match the general rural consumption trends, and more importantly, how to translate public perception into a behavior change.

“I think it’s really important to look into the behavioral aspect,” said Kar in an interview. “If you ask someone if they think clean cooking is wise they may say yes, but if you say do you think it is appropriate for you? The moment it becomes personalized the answers can vary.”

Kar knows that although more than 41 million LPG connections have been installed, installment of the connection does not necessarily equate to use. By gathering data on LPG refill purchases and trends, along with surveys that identify biases in the public’s perception, he wants to know how to convince rural BPL households to maintain the habit of using LPG regularly, even under adverse conditions like price hikes. If LPG is used only sporadically, LPG ownership won’t significantly reduce risk for some household air pollution (HAP)-linked deadly diseases, like lower respiratory infections and stroke.

Unfortunately, even the substantial efforts the government has made to improve LPG supply has not changed the public’s perception of its accessibility in the long term, nor its consumption patterns in the first two years. At least four LPG refills per year would be needed for a family of five to use LPG as a primary cooking fuel, which is not currently happening for the majority of Ujjwala customers.

Because the majority of Ujjwala beneficiaries have cost-free access to solid fuels from forest and agricultural fields, there is less incentive for these families to use LPG regularly instead of sporadically. Priority households for Ujjwala, especially those with no working age adults, are often severely economically disadvantaged and can’t afford to buy LPG at regular intervals.

Furthermore, unlike LPG, a traditional mud stove is more versatile and can serve dual purposes of space heating and cooking during winter months. Many prospective customers are also hesitant about the inferior taste of food cooked in LPG, the utility of the mud stove’s smoke as insect repellent, and the trade-off of expenses on tobacco and alcohol with LPG refills.

As per past studies, even the richest 10% of India’s rural households (most with access to LPG) continue to depend on solid fuels to meet ~50% of their cooking energy demand. This suggests that wealth is not the only stumbling block in the transition process.

“Whatever factors matter in the outside world, my working hypothesis is that every decision is finally mediated through a person’s attitude, knowledge, and perceptions of control,” said Kar. According to Kar, interventions can be specifically targeted to address factors that are perceived negatively either by informing people or doing something to improve that factor. Nevertheless, developing effective interventions is no simple task.

Even with a background in physics and management and eight years of experience helping people transition from one technology to another, Kar says he is grateful to have the input of a variety of scholars at IIASA, each with a different perspective and a different set of core skills and experiences. Working in the Energy program alongside IIASA staff and fellow YSSPers from all over the world, Kar puzzles out the unsolved challenge of how to create change for the rural poor.

“That has been one of my drivers, I take it as an intellectual challenge,” said Kar. “Is there a systems approach to the problem?”

For now, Kar is happy if he can return at the end of the day to his family, which he brought with him to Austria during his time as a YSSP participant, feeling like he is opening the door to a vast literature on technology adoption and human behavior, yet untapped in the field of cooking energy access.

“This research is only a very small baby step into trying something different,” said Kar, “I think this sector has so many unanswered questions, if I can at least flag that there is a lot of literature out there in other domains and maybe we can use some of it, I think that would be good enough for me.”

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 9, 2018 | Alumni, Communication, IIASA Network, South Africa, Systems Analysis, Young Scientists

By Sandra Ortellado, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2018

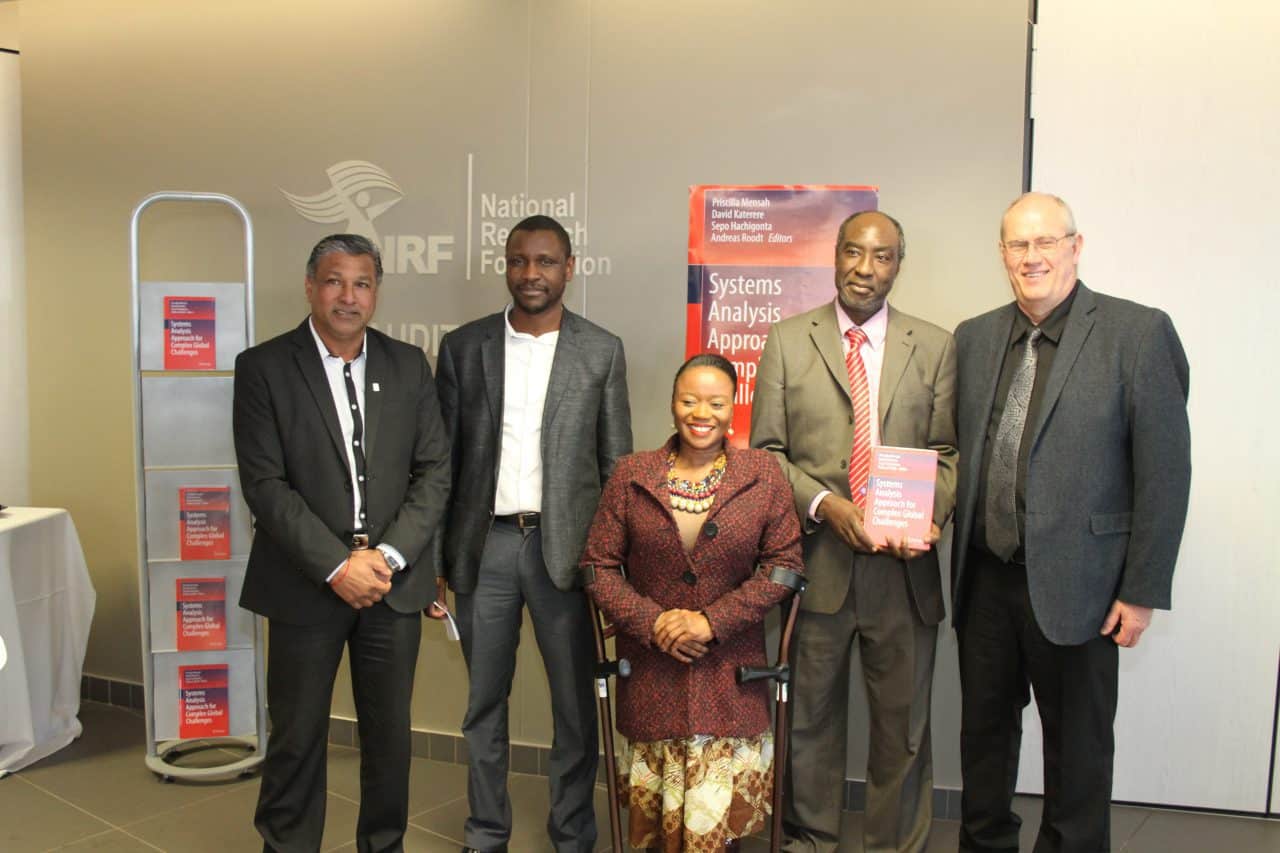

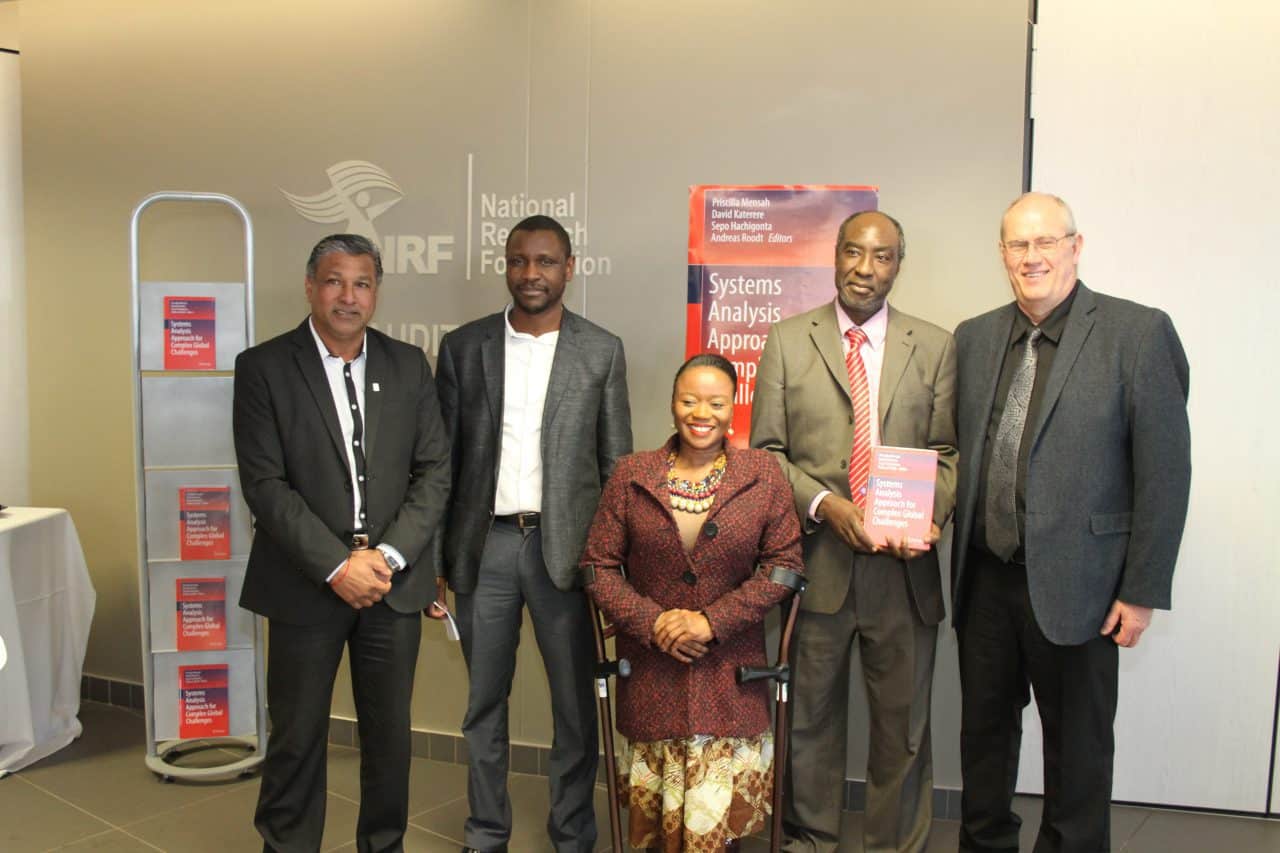

In 2007, Sepo Hachigonta was a first-year PhD student studying crop and climate modeling and member of the YSSP cohort. Today, he is the director in the strategic partnership directorate at the National Research Foundation (NRF) in South Africa and one of the editors of the recently launched book Systems Analysis for Complex Global Challenges, which summarizes systems analysis research and its policy implications for issues in South Africa.

From left: Gansen Pillay, Deputy Chief Executive Officer: Research and Innovation Support and Advancement, NRF, Sepo Hachigonta, Editor, Priscilla Mensah, Editor, David Katerere, Editor, Andreas Roodt Editor

But the YSSP program is what first planted the seed for systems analysis thinking, he says, with lots of potential for growth.

Through his YSSP experience, Hachigonta saw that his research could impact the policy system within his home country of South Africa and the nearby region, and he forged lasting bonds with his peers. Together, they were able to think broadly about both academic and cultural issues, giving them the tools to challenge uncertainty and lead systems analysis research across the globe.

Afterwards, Hachigonta spent four years as part of a team leading the NRF, the South African IIASA national member organization (NMO), as well as the Southern African Young Scientists Summer Program (SA-YSSP), which later matured into the South African Systems Analysis Centre. The impressive accomplishments that resulted from these programs deserved to be recognized and highlighted, says Hachigonta, so he and his colleagues collected several years’ worth of research and learning into the book, a collaboration between both IIASA and South African experts.

“After we looked back at the investment we put in the YSSP, we had lots of programs that were happening in South Africa, and lots of publications and collaboration that we wanted to reignite,” said Hachigonta. “We want to look at the issues that we tackled with system analysis as well as the impact of our collaborations with IIASA.”

Now, many years into the relationship between IIASA and South Africa, that partnership has grown.

Between 2012 and 2015, the number of joint programs and collaborations between IIASA and South Africa increased substantially, and the SA-YSSP taught systems analysis skills to over 80 doctoral students from 30 countries, including 35 young scholars from South Africa.

In fact, several of the co-authors are former SA-YSSP alumni and supervisors turned experts in their fields.

“We wanted to use the book as a barometer to show that thanks to NMO public entity funding, students have matured and developed into experts and are able to use what they learned towards the betterment of the people,” says Hachigonta. The book is localized towards issues in South Africa, so it will bring home ideas about how to apply systems analysis thinking to problems like HIV and economic inequality, he adds.

“It’s not just a modeling component in the book, it still speaks to issues that are faced by society.”

Complex social dilemmas like these require clear and thoughtful communication for broader audiences, so the abstracts of the book are organized in sections to discuss how each chapter aligns systems analysis with policymaking and social improvement. That way, the reader can look at the abstract to make sense of the chapter without going into the modeling details.

“Systems analysis is like a black box, we do it every day but don’t learn what exactly it is. But in different countries and different sectors, people are always using systems analysis methodologies,” said Hachigonta, “so we’re hoping this book will enlighten the research community as well as other stakeholders on what systems analysis is and how it can be used to understand some of the challenges that we have.”

“Enlightenment” is a poetic way to frame their goal: recalling the age of human reason that popularized science and paved the way for political revolutions, Hachigonta knows the value of passing down years of intellectual heritage from one cohort of researchers to the next.

“You are watching this seed that was planted grow over time, which keeps you motivated,” says Hachigonta.

“Looking back, I am where I am now because of my involvement with IIASA 11 years ago, which has been shaping my life and the leadership role I’ve been playing within South Africa ever since.”

Jun 18, 2018 | Alumni, Ecosystems, Environment, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Cecile Godde, PhD student at the University of Queensland, Australia and former IIASA YSSP participant

Cecile Godde ©Oli Sansom

Last year, I had the fantastic opportunity to spend three months at IIASA as part of the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), to collaborate with the Ecosystems Services and Management (ESM) research program. During this very enriching experience, both intellectually, socially, and culturally, I worked with Petr Havlik, David Leclère, and Christian Folberth on modeling global rangelands and pasturelands under farming and climate scenarios. I also progressed on the development of a global animal stocking rate optimizer. The overall objective of this YSSP project, and more broadly of my PhD, is to assess the role of grazing systems in a sustainable food system.

However, my trip to IIASA was not my only adventure last year. Just before moving to Vienna, I received the great news that I was selected along with 77 other women to take part in a women in science and leadership program called Homeward Bound.

What would our world look like if women and men were equally represented, respected, and valued at the leadership table? How might we manage our resources and our communities differently? How might we coordinate our response to global problems like food security and climate change?

Homeward Bound is a worldwide and world-class initiative that seeks to support and encourage women with scientific backgrounds into leadership roles, believing that diversity in leadership is key to addressing these complex and far-reaching issues. The program’s bold mission is to create a 1000-strong collective of women in science around the world over the next 10 years, with the enhanced leadership, strategic, and visibility capacity to influence policy and decision making for the benefit of the planet.

Antarctic penguins © Cecile Godde

This year-long program culminated in an intensive three-week training course in Antarctica, a journey from which I have just come back. The voyage to Antarctica was incredible. We learnt intensively during this 24/7 floating conference in the midst of majestic icebergs, very cute penguins, graceful whales, and extraordinary women from various cultures and backgrounds, from PhD students to Nobel Laureates. I have returned full of hope for the planet, deeply inspired, and emotionally energized. It was a truly unforgettable experience, one that will keep me reflecting for a lifetime.

Our days in Antarctica typically followed a similar routine – half of the day was dedicated to a landing (we visited Argentinian, Chinese, US, and UK research stations) and the other half to classes and workshops. We discussed systemic gender issues and learnt about leadership styles, peer-coaching, the art of providing feedback, science communication, core personal values, or what matter to us. The list goes on! We were also encouraged to practice reflective journaling. Regularly recording activities, situations, and thoughts on paper is actually a very powerful technique for self-discovery and personal and professional growth as it helps us think in a critical and analytical way about our behaviors, values, and emotions. We also spent quite some time developing our personal and professional strategies: What is our purpose as individuals? What are our core values, aspirations, and short- and long-term goals? From that, we developed a roadmap that could be executed as soon as we stepped off the ship. While I haven’t solved all my life’s mysteries, this activity gave me strong foundations to keep growing and actively shape my own life, rather than letting society do it for me.

In the evenings, we watched our film faculty sharing their tips with us on television, including primatologist Jane Goodall, world leading marine biologist Sylvia Earle, and former Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC), Christiana Figueres. We also had a collective art project called “Confluence: A Journey Homeward Bound”, which was underpinned by our inner journey of reflection, growth, and transformation and our outer physical journey to Antarctica.

Homeward Bound in Antarctica © Oli Sansom

Both my stay at IIASA and my journey to Antarctica taught me a lot about the value of getting out of my comfort zone, exploring different leadership styles, and collaborating. I have also witnessed how visibility (visibility to ourselves, to understand who we are, and visibility to others, to let the world know we exist) helps to open up opportunities. The good news is that the beliefs we have about ourselves are just that – beliefs – and these beliefs can be changed.

My visibility to others has also increased notably in relation to my involvement in Homeward Bound and my recent award of the Queensland Women in STEM prize. This Australian annual prize, awarded by the Minister for Environment and Science, Leeanne Enoch and Acting Chief Scientist Dr Christine Williams, aims to celebrate the achievements of women who are making a difference in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. As a result, I have been contacted by fascinating people from various fields of work, from researchers and teachers to entrepreneurs, start-ups, and industries. All these connections have broadened my approach to food security and global change and helped me shape my research vision, purpose, and values.

When we were in Antarctica, our story reached 750 million people. Why? Because, and may we never forget, the world believes in us – ‘us’ in its broadest sense: humans, scientists, women, etc. – in our skill, compassion, and capability. While we are facing alarming global social, economic, and environmental challenges, I believe that the many collaborations that embrace diversity of knowledge, skills, processes, and leadership styles that are currently emerging all around the world, will help us get closer to our development goals.

Homeward Bound is a 10-year long initiative. Find out more about the program and how to apply here: http://homewardboundprojects.com.au

Follow my journey: –

You must be logged in to post a comment.