Dec 7, 2020 | Biodiversity, Climate Change, Food & Water, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Shorouk Elkobros, 2020 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Being mindful of biodiversity loss and environmental impact can disrupt the beef industry globally, here’s how.

In his new polemical Netflix documentary, A life on our planet, Sir David Attenborough argues that, “We live on a finely tuned life support machine, one that relies on its biodiversity to run smoothly.”

The decline in biodiversity challenges the world’s capacity to produce food for a growing population. That is ironic when global food production itself is a contributing factor to biodiversity loss, especially beef production.

What’s wrong with the beef industry?

Here are a couple of the current challenges facing the beef industry: Cows are major culprits in climate change because they emit methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Beef production is the number one driver of deforestation and habitat loss in tropical forests. Grazing cattle also require a large amount of grass that requires using harsh nitrogen fertilizers. Hence, the beef production industry contributes heavily to biodiversity loss, which has dire consequences for the planet.

©Jonathan Casey | Dreamstime.com

There is no silver bullet to solve the challenges beef production poses to the environment. Research is going above and beyond to find diverse and integrated solutions that can go hand in hand to combat this challenge. Whether through ways to reduce methane emissions, such as creating an anti-burp vaccine for cows, designing lab-grown meat, or shifting diets to plant-based alternatives.

Katie Lee, an alumna of the 2020 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) and PhD student at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, is part of a broader project that focuses on redistributing where we produce beef to minimize its impact on greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity, as well as on the cost of production.

“I am particularly interested in ways to enhance the types of beef production systems. With the challenges of its water use, greenhouse gas emissions, and the large areas of land it requires compared to any other food source, any small changes we propose can have a big impact,” she explains.

For Lee, solutions to global food security are crucial, and looking at the status of production systems is both a need and a must. The world population is expected to reach 9.7 billion people by 2050. So, when thinking about ways to feed 10 Billion people by 2050, it becomes clear that it is not enough to simply look at beef alternatives without enhancing its current demand and supply chains. Lee thinks it is more efficient to pragmatically alter and improve the environmental impact of beef production than to convince people to stop eating beef.

It is understood that reducing beef consumption has health benefits. However, with a growing interest in alternative meat options, the question remains of which markets this appeals to, and how environmentally friendly and energy- and water intensive these alternatives are.

“While demand reduction on meat is important, sometimes it is not feasible in countries that do not have economic security or are still growing in terms of affluence, which leads to an increase in beef consumption. That is why we need to look at the producer side and the consumer side, as well as everything in between to have the biggest impact. I was particularly interested to conduct this research in cooperation with IIASA, mainly because the institute has a good history of looking at the impact of beef, particularly in terms of greenhouse gas emissions,” says Lee.

A win-win all-round solution

Using the IIASA Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM), Lee is assessing the impact on greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity when shifting both the production and demand of beef. Preliminary results from her ongoing study show a reduction in impact on biodiversity and greenhouse gas emissions, as well as a reduction of the producer price when switching away from extensive grazing systems ̶ a win-win situation all-round.

“Few studies explicitly address biodiversity loss compared to investigating ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. I want to show stakeholders that beef production can be more efficient in terms of reducing its impact on greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity. I am hopeful that this study can help beef producers to be mindful of this when making choices. That will be a win for the environment if it goes together with a proactive reduction of meat consumption,” concludes Lee.

Similar to Lee’s study and using a set of large-scale economic models including GLOBIOM, the IIASA AnimalChange research project aims to assess the global scale adaptation and mitigation options of the livestock sector to ensure a sustainable livestock production sector by 2050.

Limiting global warming and protecting biodiversity should be a priority when designing food systems able to feed an increasing population. As a food producer, whether you raise cattle or design cell cultured meat, it is important to be conscious about livestock hoof prints on biodiversity. As a food consumer, it is necessary to be mindful of having a healthy and sustainable diet that does not put the planet in jeopardy. Sustainable beef production might not be the panacea to future biodiversity loss or food scarcity, yet it can offer a significant change.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 14, 2020 | Alumni, Postdoc, Sustainable Development, Women in Science

By Raquel Guimaraes, postdoc in the IIASA World Population Program, and Debbora Leip, an alumnus of the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program

IIASA researcher Raquel Guimaraes and former research assistant Debbora Leip encourage the support of the Cercedilla Manifesto, arguing that it is high time for the scientific community to take responsibility and set an example by making research meetings more sustainable.

© La Fabrika Pixel S.l. | Dreamstime.com

The research community widely agrees that strong action is needed to counteract the climate crisis that is currently taking place. Nevertheless, scientists regularly meet at conferences that are often far from sustainable. Problems range from participants flying to attend events, to unnecessary gadgets and gifts handed out at the meetings, and unsustainable catering at conference dinners. In light of the current public debate on environmental and social sustainability, we call on scientists to take a leading role in changing their work practices towards more sustainable habits, starting with research meetings.

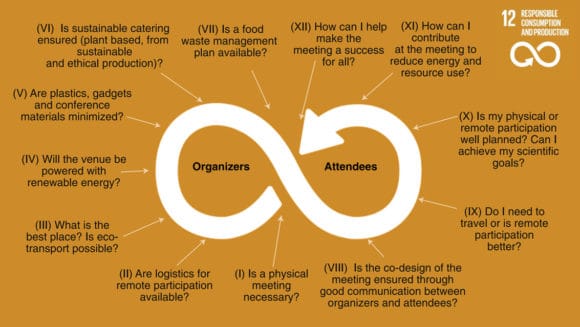

In April 2020, Alberto Sanz-Cobena and several colleagues published an article titled Research meetings must be more sustainable in Nature Foods. They presented the Cercedilla Manifesto with 12 sustainability decisions as guidelines for organizers and attendees of research meetings (see Figure 1). The starting point of the manifesto is to question whether a physical meeting is indeed necessary. If organizers decide that it is, there is still the question of whether each single attendee really needs to physically join the conference. Often, remote participation can be equally efficient if a technical solution is provided by the organizers. Furthermore, if a decision to conduct a physical meeting is taken, organizers have to consider what food will be served.

The authors state that excessive amounts of food and food waste are very common at meetings, which makes a change of mindset towards better food management very important, not only for climate change, but for many other environmental threats. In our opinion, this point has so far been neglected in public debate.

Given the urgency for climate change action and the need for individuals to play an active role – with research scientists taking the lead – we assert that it is urgent to start changing our habits and setting an example regarding environmental and social sustainability in research meetings. Indeed, many of us take it for granted that to meet and discuss our work, we must travel. Most attendees do not even question that unnecessary gadgets and gifts are distributed or that opulent dinners are provided.

We hope that the Cercedilla Manifesto will raise awareness about the fact that good scientific output often does not require a physical meeting by providing a conceptual framework for change in this regard. If we support the manifesto, we stand a chance to lower the barrier to dare deviating from currently applied practices. The 12-sustainability decisions were designed by specialists to serve as a reference for anybody who wishes to organize/attend a sustainable meeting.

In the current situation brought about by the global COVID-19 crisis, almost everybody has experienced that remote conferences are not only possible, but also efficient – sometimes even more so than a physical meeting would have been. First, it saves time in terms of travel. Second, it may be more inclusive by allowing people to attend, who would not have had the opportunity to join otherwise, be it for financial, family, or other reasons. In addition, remote meetings provide additional features, like a chat function that could add another discussion layer.

Of course, remote meetings also have their limitations: informal in-person meetings during coffee breaks, for example, can enhance networking and free discussions, and sometimes contribute significantly to a meeting’s outcome. Virtual meetings also face several other challenges, such as participation by attendees from different time zones, or poor internet connections. These issues could however easily be addressed by spreading the meeting over more days, in such a way that the need for attendance outside of acceptable time slots is minimized, and by investing saved traveling costs into better equipment.

Let us learn from this experience and not go ‘back to normal’ after the COVID-19 crisis. We should take this as an opportunity to speed up change and tackle the other global crisis of climate change!

You can find the petition at openpetition.eu/!cercedillamanifesto. We encourage you to share and support this initiative.

References:

Sanz-Cobena A, Alessandrini R, Bodirsky BL, Springmann M, Aguilera E, Amon B, Bartolini F, Geupel M, et al. (2020). Research meetings must be more sustainable. Nature Food 1, 187–189. DOI: 10.1038/s43016-020-0065-2

Frisch B, & Greene C (2020). What it takes to run a great virtual meeting. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/03/what-it-takes-to-run-a-great-virtual-meeting?ab=hero-subleft-3

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 23, 2019 | Austria, Science and Policy

By Jan Marco Müller, IIASA Acting Chief Operations Officer

Jan Marco Müller shares his insights into the recent high-level forum in Vienna that brought together science advisors to ministers of foreign affairs from across the world and other experts in the practice, theory, and discussion of science diplomacy.

Established following an initiative by the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, IIASA can be considered a child of diplomacy for science. At the same time, the institute has always been one of the world’s premier vehicles of science for diplomacy, by using science to build bridges between nations including those with special relations. However, there is another dimension of science diplomacy which has gained traction in recent years: the support scientists can provide to diplomats and policymakers in the foreign policy domain – known as science in diplomacy.

© IIASA

As global challenges become more complex and interdependent and technological progress advances at an ever-increasing speed, the scientific-technical dimension of foreign policies has gained increasing attention. This is illustrated by four examples:

- Climate change impacts everybody on the planet, regardless of national borders.

- Many digital technologies escape national jurisdictions and so create tensions between nations: e.g. cryptocurrencies, deep fakes, and internet trolls.

- Trade agreements are often hampered by disagreements on technical standards, which themselves are influenced by societal values: people may still remember the discussions around chlorinated chicken in the US-EU trade negotiations a few years ago.

- National interests are increasingly entering international spaces, which in the past have been governed by science, such as the Arctic/Antarctic, the deep sea and outer space.

Ministries of foreign affairs and diplomatic services around the world are all confronted with similar issues and critically depend on advice provided by scientists.

With this in mind, on 25-26 November 2019 IIASA, together with the International Network for Government Science Advice (INGSA), the Austrian Federal Ministry of Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs, the Diplomatische Akademie Wien (Vienna School of International Studies), and the Natural History Museum Vienna, held the global meeting of the Foreign Ministries Science & Technology Advice Network (FMSTAN).

FMSTAN gathers science advisors to ministers of foreign affairs from around the planet, providing a platform for the exchange of information and best practices. IIASA hosted the first meeting of this network in October 2016, which has since grown significantly, with some 50 countries now participating in its biannual meetings.

The global meeting in November was organized back to back with the meetings of two other important networks in the science diplomacy arena: the Science Policy in Diplomacy and External Relations Network (SPIDER) – which is the science diplomacy branch of the International Network for Government Science Advice – and the Big Research Infrastructures for Diplomacy and Global Engagement through Science (BRIDGES) Network. BRIDGES was established a year ago following an initiative by my colleague Maurizio Bona at CERN and myself, with the aim of uniting the science diplomacy officers of all major international research infrastructures. In addition, a 3-day training course organized by the EU-funded project Using science for/in diplomacy for addressing global challenges (S4D4C) was arranged in parallel to achieve maximum synergies.

© IIASA (L-R): Jan Marco Müller and Jeffrey Sachs, Special Advisor to the UN Secretary-General on SDGs; Director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, NY.

The meetings were attended by around 100 science diplomats including the President-elect of the International Science Council Sir Peter Gluckman, the UN Advisor on the Sustainable Development Goals Jeffrey Sachs, the former Rector of the University for Peace of the UN Martin Lees, the S&T Advisor to the US Secretary of State Matt Chessen, the S&T Advisor to the Japanese Foreign Minister Teruo Kishi, the Science Diplomacy Advisor to the Mexican Foreign Minister José Ramón López Portillo, and the Chief Science Advisor in the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs Dirk-Jan Koch, to name just a few.

Six major topics were discussed:

- The role of science diplomacy in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

- The importance of science in international security policies

- The challenges for science diplomacy in the current geopolitical environment

- Technology Diplomacy

- The role of science in diplomatic curricula (and vice versa)

- Future challenges for science diplomacy and the role of systemic thinking in policymaking

The Vienna meeting offered a unique platform for all those who “speak science” in the diplomatic arena to exchange ideas and experiences, while fostering a common global agenda. For additional insights I recommend reading the piece “Science Diplomacy: A Pragmatic Perspective from the Inside” which aims at making the term science diplomacy more operational – all the four authors participated to the Vienna meeting.

Overall the event demonstrated once again the convening power of IIASA and the leadership of the institute in confirming Vienna as one of the global hubs for science diplomacy.

© Mahmood | BMEIA. FMSTAN/SPIDER members and participants of the S4D4C training course.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 4, 2019 | Ecosystems, Environment, IIASA Network

By Brian Fath, Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) scientific coordinator, researcher in the Advanced Systems Analysis Program, and professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Towson University (Maryland, USA) and Soeren Nors Nielsen, Associate professor in the Section for Sustainable Biotechnology, Aalborg University, Denmark

IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) scientific coordinator, Brian Fath and colleagues take an extended look at the application of the ecosystem principles to environmental management in their book, A New Ecology, of which the second edition was just released.

IIASA is known for some of the earliest studies of ecosystem dynamics and resilience, such as work done at the institute under the leadership of Buzz Holling. The authors of the book, A New Ecology, of which the second edition was just released, are all systems ecologists, and we chose to use IIASA as the location for one of the brainstorming meetings to advance the ideas outlined in the book. At this meeting, we crystallized the idea that ecosystem ontology and phenomenology can be summarized in nine key principles. We continue to work with researchers at the institute to look for novel applications of the approach to socioeconomic systems – such as under the current EU project, RECREATE – in which the Advanced Systems Analysis Program is participating. The project uses ecological principles to study urban metabolism – a multi-disciplinary and integrated platform that examines material and energy flows in cities as complex systems.

IIASA is known for some of the earliest studies of ecosystem dynamics and resilience, such as work done at the institute under the leadership of Buzz Holling. The authors of the book, A New Ecology, of which the second edition was just released, are all systems ecologists, and we chose to use IIASA as the location for one of the brainstorming meetings to advance the ideas outlined in the book. At this meeting, we crystallized the idea that ecosystem ontology and phenomenology can be summarized in nine key principles. We continue to work with researchers at the institute to look for novel applications of the approach to socioeconomic systems – such as under the current EU project, RECREATE – in which the Advanced Systems Analysis Program is participating. The project uses ecological principles to study urban metabolism – a multi-disciplinary and integrated platform that examines material and energy flows in cities as complex systems.

Our book argues the need for a new ecology grounded in the first principles of good science and is also applicable for environmental management. Advances such as the United Nations Rio Declaration on Sustainable Development in 1992 and the more recent adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (2015) have put on notice the need to understand and protect the health and integrity of the Earth’s ecosystems to ensure our future existence. Drawing on decades of work from systems ecology that includes inspiration from a variety of adjacent research areas such as thermodynamics, self-organization, complexity, networks, and dynamics, we present nine core principles for ecosystem function and development.

The book takes an extended look at the application of the ecosystem principles to environmental management. This begins with a review of sustainability concepts and the confusion and inconsistencies of this is presented with the new insight that systems ecology can bring to the discussion. Some holistic indicators, which may be used in analyzing the sustainability states of environmental systems, are presented. We also recognize that ecosystems and society are physically open systems that are in a thermodynamic sense exchanging energy and matter to maintain levels of organization that would otherwise be unattainable, such as promoting growth, adaptation, patterns, structures, and renewal.

Another fundamental part of the evolution of the just mentioned systems are that they are capable of exhibiting variation. This property is maintained by the fact that the systems are also behaviorally open, in brief, capable of taking on an immense number of combinatorial possibilities. Such an openness would immediately lead to a totally indeterminate behavior of systems, which seemingly is not the case. This therefore draws our attention towards a better understanding of the constraints of the system.

One way of exploring the interconnectivity in ecosystems is taking place mainly through the lens of ecological network analysis. A primer for network environment analysis is provided to familiarize the reader with notation including worked examples. Inherent in energy flow networks, such as ecosystem food webs, the real transactional flows give rise to many hidden properties such as the rise in indirect pathways and indirect influence, an overall homogenization of flow, and a rise in mutualistic relations, while hierarchies represent conditions of both top-down and bottom-up tendencies. In ecosystems, there are many levels of hierarchies that emerge out of these cross-time and space scale interactions. Managing ecosystems requires knowledge at several of these multiple scales, from lower level population-community to upper level landscape/region.

Viewing the tenets of ecological succession through a lens of systems ecology lends our attention the agency that drives the directionality stemming from the interplay and interactions of the autocatalytic loops – that is, closed circular paths where each element in the loop depends on the previous one for its production – and their continuous development for increased efficiency and attraction of matter and energy into the loops. Ecosystems are found to show a healthy balance between efficiency and redundancy, which provides enough organization for effectiveness and enough buffer to deal with contingencies and inevitable perturbations.

Yet, the world around us is largely out of equilibrium – the atmosphere, the soils, the ocean carbonates, and clearly, the biosphere – selectively combine and confine certain elements at the expense of others. These stable/homoeostatic conditions are mediated by the actions of ecological systems. Ecosystems change over time displaying a particular and identifiable pattern and direction. Another “unpleasant” feature of the capability for change is to further evolve through collapses. Such collapse events open up creative spaces for colonization and the emergence of new species and new systems. This pattern includes growth and development stages followed by the collapse and subsequent reorganization and launching to a new cycle.

A good theory should be applicable to the concepts in the field it is trying to influence. While the mainstream ecologists are not regularly applying systems ecology concepts, the purpose of our book is to show the usefulness of the above ecosystem principles in explaining standard ecological concepts and tenets. Case studies from the general ecology literature are given relating to evolution, island bio-geography, biodiversity, keystone species, optimal foraging, and niche theory to name a few.

No theory is ever complete, so we invite readers to respond and comment on the ideas in the book and offer feedback to help improve the ideas, and in particular the application of these principles to environmental management. We see a dual goal to understand and steward ecological resources, both for their sake and our own, with the purpose of an ultimate sustainability.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 21, 2019 | Air Pollution, Environment, Food & Water, Indonesia, Women in Science

By Adriana Gómez-Sanabria, researcher in the IIASA Air Quality and Greenhouse Gases Program

Adriana Gómez-Sanabria discusses the results of a new study that looked into the impacts of implementing various technologies to treat wastewater from the fish processing industry in Indonesia.

© Mikhail Dudarev | Dreamstime.com

To reduce water pollution and climate risks, the world needs to go beyond signing agreements and start acting. Translating agreements and policies into action is however always much more difficult than it might seem, because it requires all players involved to participate. A complete integration strategy across all sectors is needed. One of the advantages of integrating all sectors is that it would be possible to meet different objectives, for example, climate and water protection goals in this case, with the same strategy.

I was involved in a study that assessed the impacts of implementing various technologies to treat wastewater from the fish processing industry in Indonesia when involving different levels of governance. This study is part of the strategies that the government of Indonesia is evaluating to meet the greenhouse gas mitigation goals pledged in its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), as well as to reduce water pollution. Although Indonesia has severe national wastewater regulations, especially in the fish processing industry, these are not being strictly implemented due to lack of expertise, wastewater infrastructure, budgetary availability, and lack of stakeholder engagement. The objective of the study was to evaluate which technology would be the most appropriate and what levels of governance would need to be involved to simultaneously meet national climate and water quality targets in the country.

Seven different wastewater treatment technologies and governance levels were included in the analysis. The combinations included were: 1) Untreated/anaerobic lagoons – where untreated means wastewater is discharged without any treatment and anaerobic lagoons are ponds filled with wastewater that undergo anaerobic processes – combined with the current level of governance. 2) Aeration lagoons – which are wastewater treatment systems consisting of a pond with artificial aeration to promote the oxidation of wastewaters, plus activated sludge focused solely on water quality targets with no coordination between water and climate institutions. 3) Swimbed, which is an aerobic aeration tank focusing mainly on climate targets assuming no coordination between institutions. 4) Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) technology, which is an anaerobic reactor with gas recovery and use followed by Swimbed, and 5) UASB with gas recovery and use followed by activated sludge, which is an aerobic treatment that uses microorganisms forming particles that clump together. Both, 4 and 5 assume vertical and horizontal coordination between water and climate institutions at national, regional, and local level. It is important to notice that the main difference between 4 and 5 is the technology used in the second step. Two additional combinations, 6 and 7, are also proposed including the same technological combinations of 4 and 5, but these include increasing the level of governance to a multi-actor coordination level. The multi-actor level includes coordination at all institutional levels but also involves academia, research institutes, international support, and other stakeholders.

Our results indicate that if the current situation continues, there would be an increase of greenhouse gases and water pollution between 2015 and 2030, driven by the growth in fish industry production volumes. Interestingly, the study also shows that focusing only on strengthening capacities to enforce national water policies would result in greenhouse gas emissions five times higher in 2030 than if the current situation continues, due to the increased electricity consumption and sludge production from the wastewater treatment process. The benefit of this strategy would be positive for the reduction of water pollution, but negative for climate change mitigation. From our analyses of combinations 2 and 3 we learned that technology can be very efficient for one purpose but detrimental for others. If different institutions are, for example, responsible for water quality and climate change mitigation, communication between the institutions is crucial to avoid trade-offs between environmental objectives.

Furthermore, when analyzing different cooperation strategies together with a combination of diverse sets of technologies, we found that not all combinations work appropriately. For instance, improving interaction just within and between institutions does not guarantee proper selection and application of technologies. In this case, the adoption of the technology is not fast enough to meet the targets proposed in 2030, thus resulting in policy implementation failures. Our analyses of combinations 4 and 5 showed that interaction within and between national, regional, and local institutions alone is not enough to prevent policy failure.

Finally, a multi-actor cooperation strategy that includes cooperation across sectors, administrative levels, international support, and stakeholders, seems to be the right approach to ensure selection of the most appropriate technologies and achieve policy success. We identified that with this approach, it would be possible to reduce water pollution and simultaneously decrease greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity required for wastewater treatment. Analyzing combinations 6 and 7 revealed that multi-actor governance allows to simultaneously meet climate and water objectives and a high chance to prevent policy failure.

In the end, analyses such as the one shown here, highlight the importance of integrating and creating synergies across sectors, administrative levels, stakeholders, and international institutions to ensure an effective implementation of policies that provide incentives to make careful choices regarding multi-objective treatment technologies.

Reference:

Gómez-Sanabria A, Zusman E, Höglund-Isaksson L, Klimont Z, Lee S-Y, Akahoshi K, Farzaneh H, & Chairunnisa (2019). Sustainable wastewater management in Indonesia’s fish processing industry: bringing governance into scenario analysis. Journal of Environmental Management (Submitted).

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.