Aug 16, 2017 | Climate Change, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

As climate change warms up the planet, it is the Arctic where the effects are most pronounced. According to scientific reports, the Arctic is warming twice as fast in comparison to the rest of the world. That in itself is a cause for concern. However, as the region increasingly becomes ice-free in summer, making shipping and other activities possible, another threat looms large. That of an oil spill.

©AllanHokins I Flickr

While it can never be good news, an oil spill in the Arctic could be particularly dangerous because of its sensitive ecosystem and harsh climatic conditions, which make a cleanup next to impossible. With an increase in maritime traffic and an interest in the untapped petroleum reserves of the Arctic, the likelihood of an oil spill increases significantly.

Maisa Nevalainen, as part of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), is working to assess the extent of the risk posed by oil spills in the Arctic marine areas.

“That the Arctic is perhaps the last place on the planet which hasn’t yet been destroyed or changed drastically due to human activity, should be reason enough to tread with utmost caution,” says Nevalainen

Although the controversial 1989 Exxon Valdez spill in Prince William Sound was quite close to the Arctic Circle, so far no major spills have occurred in the region. However, that also means that there is no data and little to no understanding of the uncertainties related to such accidents in the region.

For instance, one of the significant impacts of an oil spill would be on the varied marine species living in the region, likely with consequences carrying far in to the future. Because of the cold and ice, oil decomposes very slowly in the region, so an accident involving oil spill would mean that the oil could remain in the ice for decades to come.

Thick-billed Murre come together to breed in Svalbard, Norway. Nevalainen’s study so far suggests that birds are most likely to die of an oil spill as compared to other animals. © AllanHopkins I Flickr

Yet, researchers don’t know how vulnerable Arctic species would be to a spill, and which species would be affected more than others. Nevalainen, as part of her study at IIASA will come up with an index-based approach for estimating the vulnerability (an animal’s probability of coming into contact with oil) and sensitivity (probability of dying because of oiling) of key Arctic functional groups of similar species in the face of an oil spill.

“The way a species uses ice will affect what will happen to them if an oil spill were to happen,” says Nevalainen. Moreover, oil tends to concentrate in the openings in ice and this is where many species like to live, she adds.

During the summer season, some islands in the region become breeding grounds for birds and other marine species both from within the Arctic and those that travel thousands of miles from other parts of the world. If these species or their young are exposed to an oil spill, then it could not only result in large-scale deaths but also affect the reproductive capabilities of those that survive. This could translate in to a sizeable impact on the world population of the affected species. Polar bears, for example, have, on an average two cubs every three years. This is a very low fertility rate – so, even if one polar bear is killed, the loss can be significant for the total population. Fish on the other hand are very efficient and lay eggs year round. Even if all their eggs at a particular time were destroyed, it would most likely not affect their overall population. However, if their breeding ground is destroyed then it can have a major impact on the total population depending on their ability and willingness to relocate to a new area to lay eggs, explains Nevalainen.

Due to lack of sufficient data on the number of species in the region as well as that on migratory population, it is difficult to predict future scenarios in case of an accident, she adds. “Depending on the extent of the spill and the ecosystem in the nearing areas, a spill can lead to anything from an unfortunate incident to a terrible disaster,” says Nevalainen.

©katiekk I Shutterstock

It might even affect the food chain, at a local or global level. “If oil sinks to the seafloor, some species run the risk of dying or migrating due to destroyed habitat – an example being walruses as they merely dive to get food from the sea floor,” adds Nevalainen. As the walrus is a key species in the food web, this has a high probability of upsetting the food chain.

When the final results of her study come through, Nevalainen aims to compare different regions of the Arctic and the probability of damage in these areas, as well as potential solutions to protect the ecosystem. This would include several factors. One of them could be breeding patterns – spring, for instance, is when certain areas need to be cordoned off for shipping activities, as most animals breed during this time.

“At the moment there are no mechanisms to deal with an oil spill in the Arctics. I hope that it never happens. The Arctic ecosystem is very delicate and it won’t take too much to disturb it, and the consequences can be huge, globally,” warns Nevalainen.

About the Researcher

Maisa Nevalainen is a third- year PhD student at the University of Helsinki, Finland. Her main focus is on environmental impacts caused by Arctic oil spills, while her main research interests include marine environment, and environmental impacts of oil spills among others. Nevalainen is working with the Arctic Futures Initiative at IIASA over the summer, with Professor Brian Fath as her supervisor and Mia Landauer and Wei Liu as her co-supervisors.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 1, 2017 | Demography, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

© KonstantinChristian I Shutterstock

Faced with a sharp decline in the global fertility levels over the last few decades, many countries today are confronted with the problem of an aging population. This could translate into an economic threat: higher health-care costs for the elderly coupled with a shrinking working population will lead to lower income-tax revenues to provide for these rising costs. This can already be seen in countries like Japan, Spain, and Germany. With an increasing number of elderly dependents and not enough workers to replace them, their social support systems have become increasingly strained.

Even though in the last few decades there has been an increase in individual incomes, researchers have observed a negative correlation between the increased wealth and the number of children people choose to have. Sara Loo, as part of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), seeks to explore why people are choosing to have fewer children as their social and economic conditions change for the better.

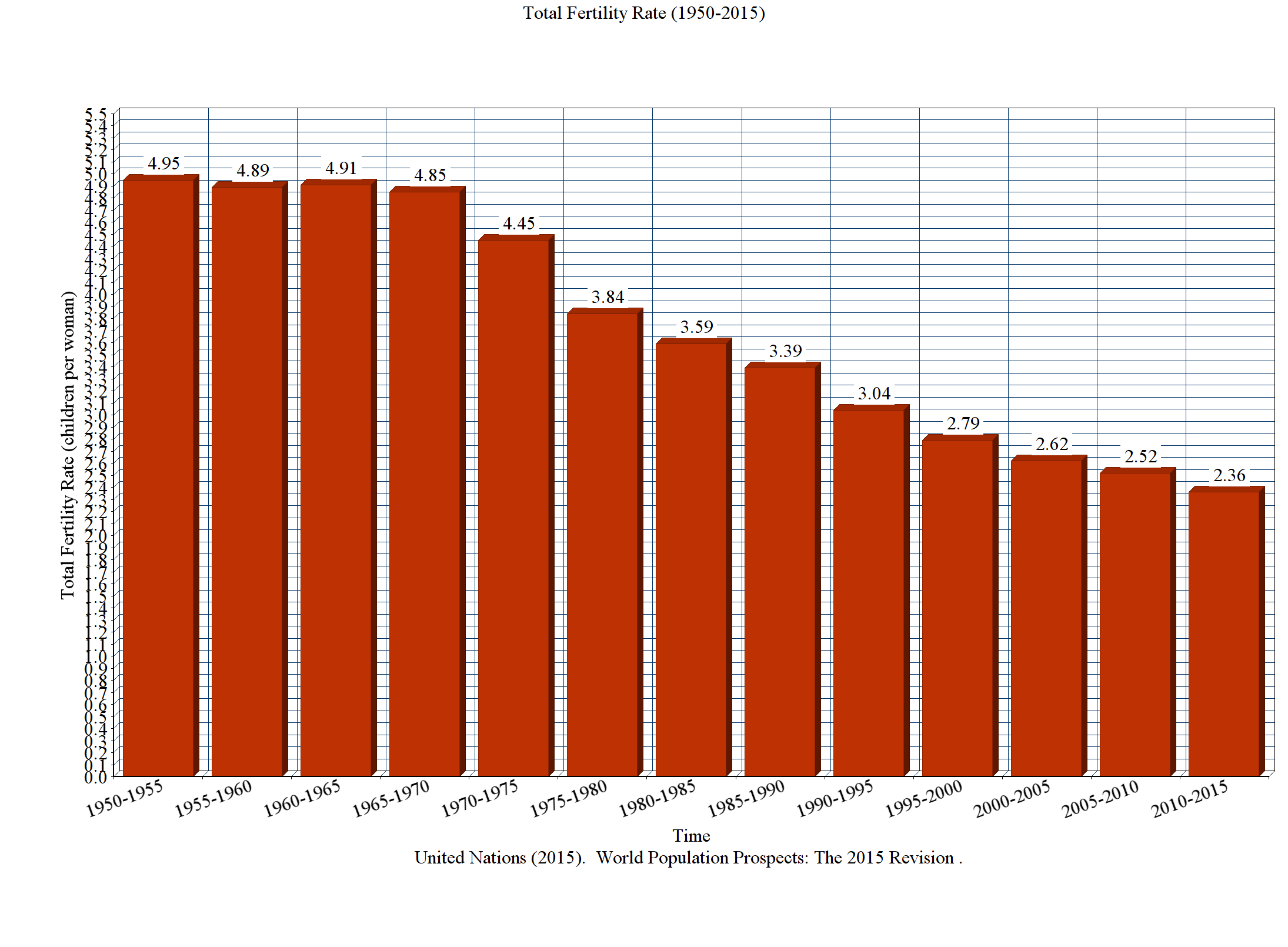

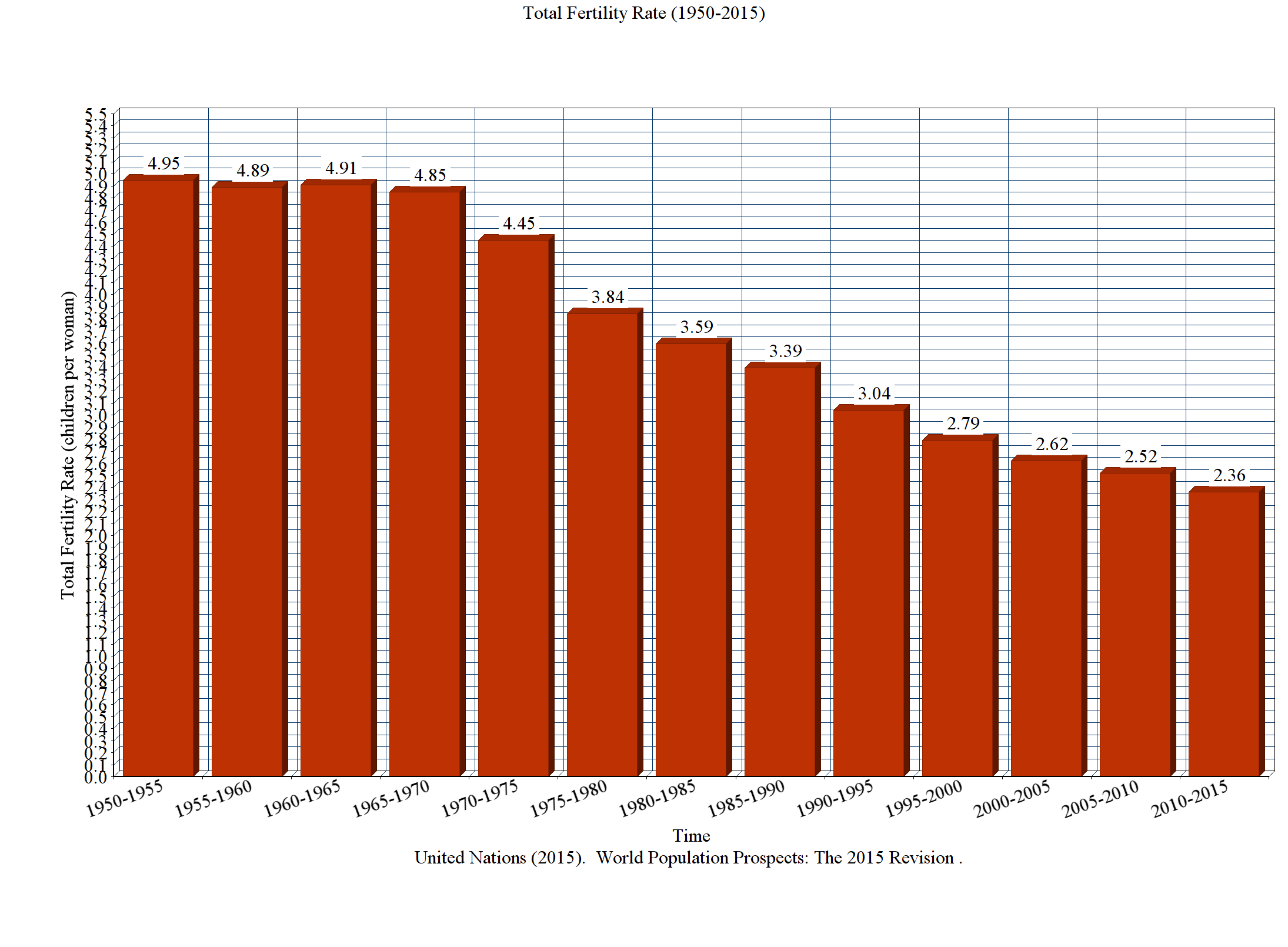

According to a report titled World Fertility Patterns 2015, global fertility levels have gone down from just above five children in 1950 to around 2.5 children per woman in 2015. In the figure below, ‘total fertility rate’ refers to the average number of children that are born to a woman over her lifetime.

It might seem counterintuitive that better living standards would be linked to decreased fertility. One way to explain it is through the lens of cultural evolution. Loo explains that culture is constantly changing – be it beliefs, knowledge, skills, or customs. This change is reflected in people’s day-to-day behaviors and affects their choices, both professional and personal. Importantly, beliefs and customs are acquired not only from people’s parents but are largely influenced by their peers – friends and colleagues.

One of the ways in which cultural evolution has affected fertility rates is resulting from the trade-off between the number of children and the quality of life that parents desire to give each of them, says Loo. As both men and women vie for well-paying jobs to attain a higher standard of living, and as they compete for such jobs based on their education, the resources parents invest into each child’s upbringing, including education and inheritance, are crucial. Even the time parents can give to their children becomes an expensive currency.

This makes for a highly competitive environment in which everyone is trying to achieve a higher status, in order to provide better opportunities for their children. When parents have fewer children, this means giving each of them a greater chance of achieving higher status.

Loo elaborates that as everyone competes to get their children to the top of the socioeconomic ladder, this necessitates a higher investment per child, both monetarily and otherwise. The theory of cultural evolution in this case thus predicts lowered fertility as competition for well-paying jobs intensifies with a country’s development.

However, it is not that such parental strategies apply equally to all segments of a population, says Evolution and Ecology Program Director Ulf Dieckmann, who is supervising Loo’s research at the institute over the summer. He explains that it is therefore helpful to look at fertility in relation to people’s socioeconomic status, instead of just looking at a population’s average fertility rate over time.

This can give telling insights. “In many pre-industrial societies, the rich had greater numbers of children, and if anybody had less than replacement-level fertility, it was the really poor people who could not afford to raise as many children. It was over time that this correlation changed from positive to negative when richer people decided to have fewer children: if they had too many children, they could not afford to invest as much per child as was needed to secure maintaining or raising the children’s socioeconomic status. This has led to a reversal of the traditional pattern: in developed societies, fertility has been shown to drop at high socioeconomic status,” says Dieckmann.

Complementing existing research on the fertility impacts of urbanization and of women’s education and liberation, Loo plans to explore how the aforementioned mechanisms of cultural evolution can explain the observed negative correlation between socioeconomic status and fertility. Her goal is to do so using a mathematical model that can account for both economic trends and cultural trends as two key processes influencing fertility rates.

About the researcher

Sara Loo is currently a third-year PhD candidate at the University of Sydney, Australia, where her research focuses on the evolution of uniquely human behaviors. Loo is working with the Evolution and Ecology Program at IIASA over the summer, with Professor Karl Sigmund and Program Director Ulf Dieckmann as her supervisors for the project.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 26, 2017 | Alumni, Climate Change, Poverty & Equity, Sustainable Development, Water, Young Scientists

Adil Najam is the inaugural dean of the Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University and former vice chancellor of Lahore University of Management Sciences, Pakistan. He talks to Science Communication Fellow Parul Tewari about his time as a participant of the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) and the global challenge of adaptation to climate change.

How has your experience as a YSSP fellow at IIASA impacted your career?

The most important thing my YSSP experience gave me was a real and deep appreciation for interdisciplinarity. The realization that the great challenges of our time lie at the intersection of multiple disciplines. And without a real respect for multiple disciplines we will simply not be able to act effectively on them.

Prof. Adil Najam speaking at the Deutsche Welle Building in Bonn, Germany in 2010 © Erich Habich I en.wikipedia

Recently at the 40th anniversary of the YSSP program you spoke about ‘The age of adaptation’. Globally there is still a lot more focus on mitigation. Why is this?

Living in the “Age of Adaption” does not mean that mitigation is no longer important. It is as, and more, important than ever. But now, we also have to contend with adaptation. Adaptation, after all, is the failure of mitigation. We got to the age of adaptation because we failed to mitigate enough or in time. The less we mitigate now and in the future, the more we will have to adapt, possibly at levels where adaptation may no longer even be possible. Adaption is nearly always more difficult than mitigation; and will ultimately be far more expensive. And at some level it could become impossible.

How do you think can adaptation be brought into the mainstream in environmental/climate change discourse?

Climate discussions are primarily held in the language of carbon. However, adaptation requires us to think outside “carbon management.” The “currency” of adaptation is multivaried: its disease, its poverty, its food, its ecosystems, and maybe most importantly, its water. In fact, I have argued that water is to adaptation, what carbon is to mitigation.

To honestly think about adaptation we will have to confront the fact that adaptation is fundamentally about development. This is unfamiliar—and sometimes uncomfortable—territory for many climate analysts. I do not believe that there is any way that we can honestly deal with the issue of climate adaptation without putting development, especially including issues of climate justice, squarely at the center of the climate debate.

COP 22 (Conference of Parties) was termed as the “COP of Action” where “financing” was one of the critical aspects of both mitigation and adaptation. However, there has not been much progress. Why is this?

Unfortunately, the climate negotiation exercise has become routine. While there are occasional moments of excitement, such as at Paris, the general negotiation process has become entirely predictable, even boring. We come together every year to repeat the same arguments to the same people and then arrive at the same conclusions. We make the same promises each year, knowing that we have little or no intention of keeping them. Maybe I am being too cynical. But I am convinced that if there is to be any ‘action,’ it will come from outside the COPs. From citizen action. From business innovation. From municipalities. And most importantly from future generations who are now condemned to live with the consequences of our decision not to act in time.

© Piyaset I Shutterstock

What is your greatest fear for our planet, in the near future, if we remain as indecisive in the climate negotiations as we are today?

My biggest fear is that we will—or maybe already have—become parochial in our approach to this global challenge. That by choosing not to act in time or at the scale needed, we have condemned some of the poorest communities in the world—the already marginalized and vulnerable—to pay for the sins of our climatic excess. The fear used to be that those who have contributed the least to the problem will end up facing the worst climatic impacts. That, unfortunately, is now the reality.

What message would you like to give to the current generation of YSSPers?

Be bold in the questions you ask and the answers you seek. Never allow yourself—or anyone else—to rein in your intellectual ambition. Now is the time to think big. Because the challenges we face are gigantic.

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 9, 2017 | Alumni, Young Scientists

Former IIASA Director Roger Levien started the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) in the summer of 1977. After 40 years the program remains one of the institute’s most successful initiatives.

The idea for the YSSP came out of your own experience as a summer student at The RAND Corporation during your graduate studies. How did that experience inspire you to start the YSSP?

At RAND I was introduced to systems analysis and to working with colleagues from many different disciplines: mathematics, computer science, foreign policy, and economics. After that summer, I changed from a Master’s in Operations Research to a PhD program in Applied Mathematics and moved from MIT to Harvard, because I knew that I needed a broad doctorate to be a RAND systems analyst.

From that point on, I carried the knowledge that a summer experience at a ripe time in one’s life, as one is choosing their post university career, can be life transforming. It certainly was for me.

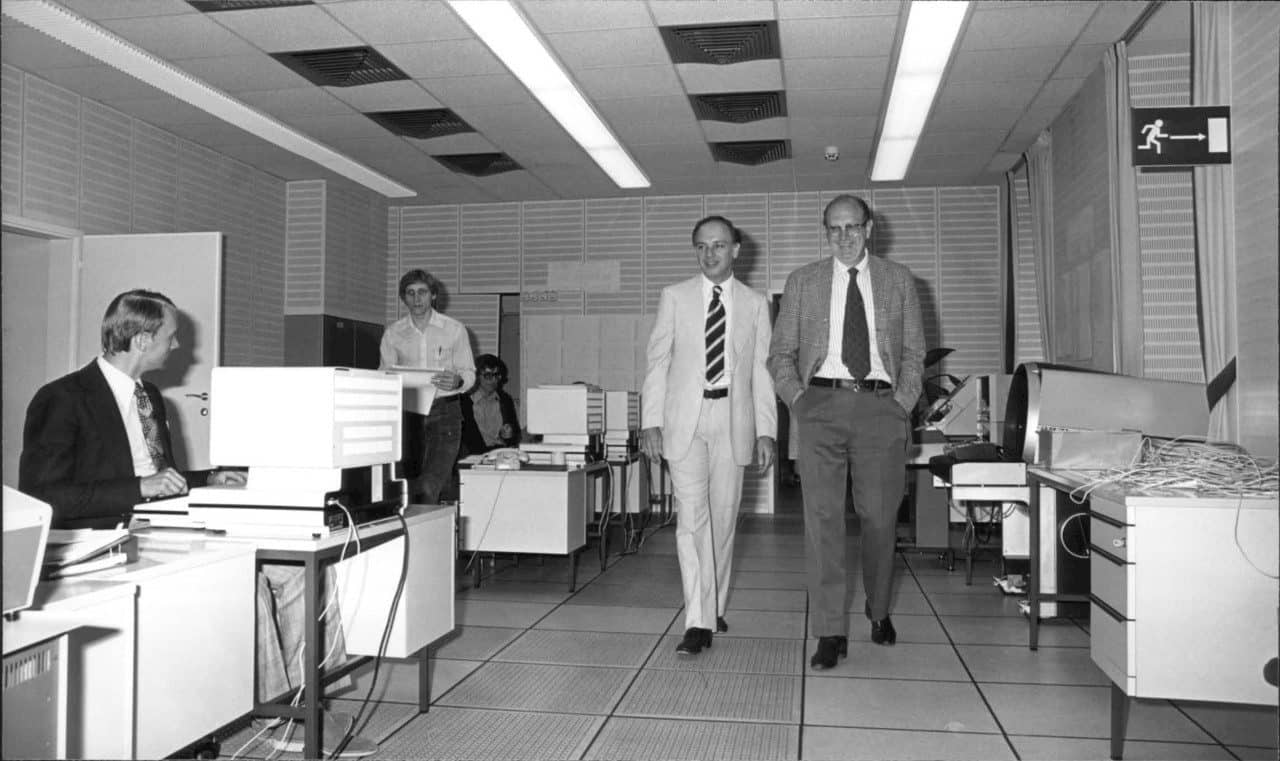

Roger Levien, left, with the first IIASA director Howard Raiffa, right. ©IIASA Archives

Why did you think IIASA would be a good place for such a summer program?

When I thought about such a program within the context of IIASA, it seemed to me that it would offer an even richer experience than mine at RAND. I thought, wouldn’t it be wonderful to bring young scientists from many nations together in their graduate-program years at IIASA. At that time, systems analysis was not well-known anywhere outside of the United States, and even there it was not very well known. In universities interdisciplinary research, and especially applied policy research, was almost nonexistent.

This would be an opportunity to introduce systems analysis to graduate students from around the world, who were otherwise deeply involved in a single discipline. It would be fruitful to bring them together to learn about the uses of scientific analysis to address policy issues, and about working both across disciplines and across nationalities.

What was your vision for the program?

I hoped that these students, who had been introduced to systems analysis at IIASA, would become an international network of analysts sharing a common understanding of international policy problems. And in the future, at international negotiations on issues of public policy, sitting behind the diplomats around the table would be technical experts, many of whom had been graduate students at IIASA, having worked on the same issue in a non-political international and interdisciplinary setting. At IIASA they would have developed a common language, a common way of thought, and perhaps working together at the negotiation they could use their shared view to help their seniors achieve success. A pipe dream perhaps, but also an ideal and a vision of what people from different countries and different disciplines who had studied the same problem with an international system analysis approach could accomplish.

Social activities have been an important component of the YSSP since the beginning ©IIASA Archives

The program is celebrating its 40th year. Why do you think it has been so successful?

I think there are many reasons for success. But for one thing, it’s my impression that just having 50 enthusiastic young scientists around brings an infusion of energy, which is a great boost to the institute. The young scientists also bring findings and methods on the cutting edges of their disciplines to IIASA.

What would be your advice to young scientists coming this summer for the 2017 program

It would be to engage as deeply as you can and as broadly as you can. This is an opportunity to learn about many things that aren’t on the curriculum of any university program. So, now’s the time to engage not only with other disciplines, but with people from other nations, to get their perspective. The people you meet this summer can be lifelong contacts. They can be your friends for life, your colleagues for life, and the opportunities that will open through them, though unpredictable, are bound to be invaluable, both professionally and personally.

This is a learning experience of an entirely different type from the typical graduate program, which goes deeper and deeper into a single discipline. You have a unique opportunity to go broader and wider, culturally, intellectually, and internationally.

IIASA will be celebrating the YSSP 40th Anniversary with an event for alumni on June 20-21, 2017.

This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 13, 2016 | Demography

By Anne Goujon, IIASA World Population Program

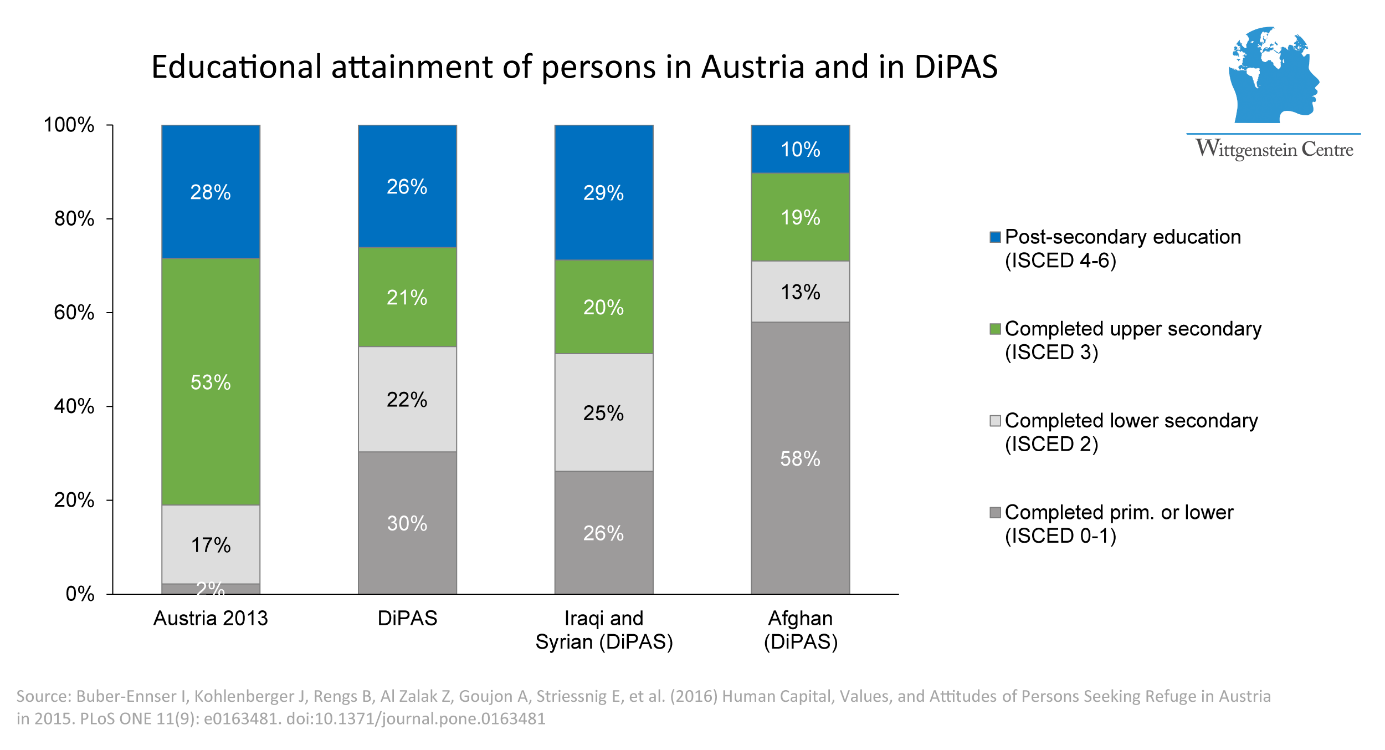

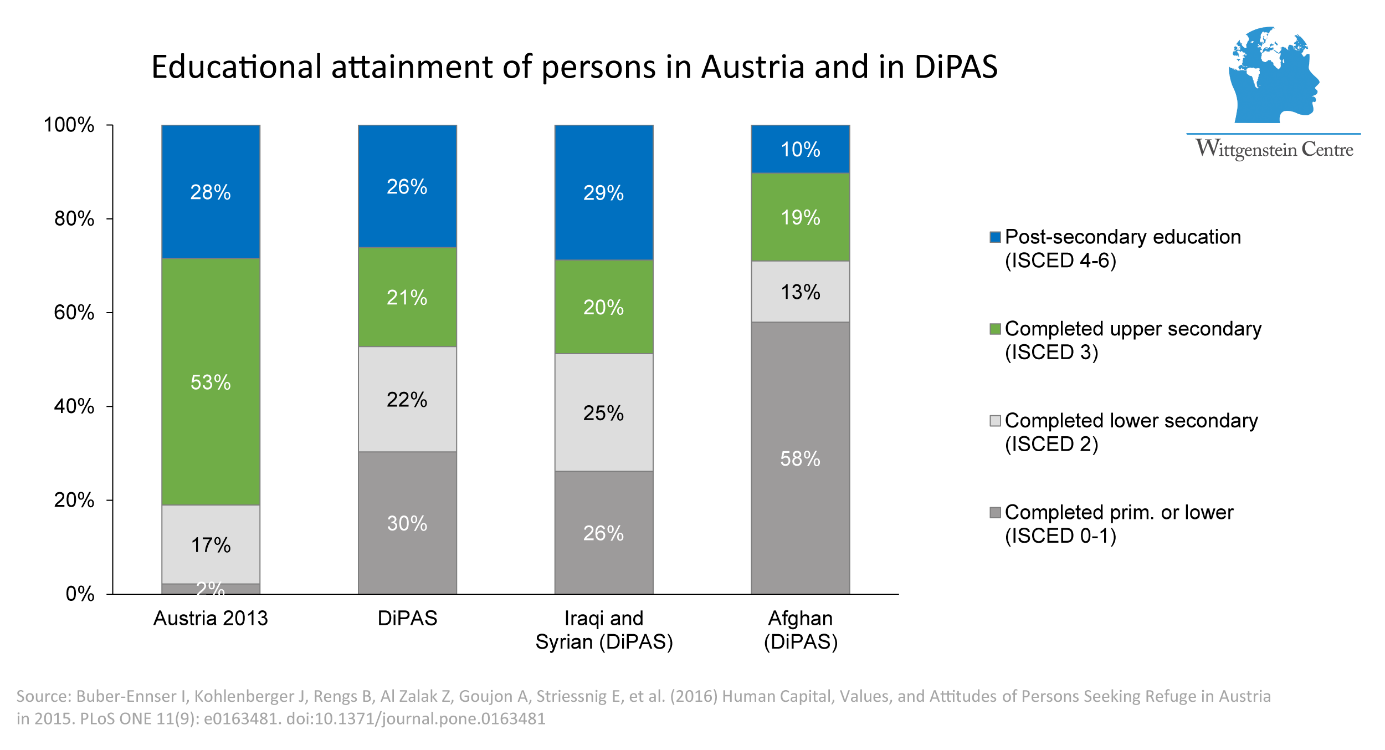

According to the Displaced Persons in Austria Survey (DIPAS) conducted by a team at the Vienna Institute of Demography and at IIASA, the large number of asylum seekers who came to Austria in the fall of 2015 appeared to possess levels of education that are higher than the average level in their country of origins. Moreover, the share of displaced persons from Syria and Iraq with a higher education is close to that of the Austrian population – around 30%.

Students at school in Beirut, Lebanon. Two-thirds of the students at the school are Lebanese and one-third of the students are Syrian. Photo © Dominic Chavez | World Bank

This seemed surprising to many, judging from the number of critical and even aggressive comments that were posted online after the results of this study appeared in PLoS ONE in September and were covered by the press, mostly in Austria. Some of these comments even suggested that people were lying, and/or that the scientists were “do-gooders” covering up the truth.

However, there are several logical reasons for these findings, none of them having anything to do with deceit. The main reason why we know the study participants were not lying is that they had no incentive to lie. They were informed about the purpose of the survey and the fact that there was nothing at stake for them besides contributing to knowledge on the refugee population. Second, their levels of education matched very well with other information they gave, for instance their previous employment, so that if lying, they were uncannily consistent. Moreover, they were rarely alone when taking the questionnaire and it is difficult for a father or mother to lie for instance in front of their children. So we tend to believe the 514 displaced persons that answered the questionnaire. But these are not our only reasons:

Not everyone can afford the adventurous trip to Austria. We asked in the survey how much their journey to Austria–mostly through Turkey–cost, and 75% reported more than 2.000 US$ per person, and 30% more than $4.000. Such a sum is not easy to come by in countries where the average salary is low. The group of asylum seekers that fled to Austria was a selected group with a higher income, and consequently more likely to have had better access to education than those who could not afford to move further and were displaced within Syria or in the neighboring countries (Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan).

Furthermore, this is a young population. Most of them are below the age of 45 years, in fact, the mean age of the respondents was 31 years. Therefore they most likely benefited from the improvements in education that were prevalent in recent times before the war started.

What we cannot say is whether the level of education in their home countries is or was equivalent to the level of education in Austria. For example, we cannot say if an engineer in informatics from the Damascus University has the same knowledge and skills as an engineer trained at the Technical University in Vienna. However, studies implemented by the Public Employment Service in Austria show that refugees’ levels of competence and skills are largely in line with their levels of education and/or occupation. Furthermore, people who successfully pursued a higher education are more likely to be willing and interested to learn new things, such as learning a new language, developing additional skills, or retraining for other professions.

Therefore, the displaced persons that came to Austria at the end of 2015 have a high potential for contributing to the economy that should not be ignored.

Reference

Buber-Ennser, I., Kohlenberger, J., Rengs, B., Al Zalak, Z., Goujon, A., Striessnig, E., Potančoková, M., Gisser, R., Testa, M.R., Lutz, W. (2016) Human Capital, Values, and Attitudes of Persons Seeking Refuge in Austria in 2015. PLoS ONE 11(9): e0163481. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163481

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.