By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

© KonstantinChristian I Shutterstock

Faced with a sharp decline in the global fertility levels over the last few decades, many countries today are confronted with the problem of an aging population. This could translate into an economic threat: higher health-care costs for the elderly coupled with a shrinking working population will lead to lower income-tax revenues to provide for these rising costs. This can already be seen in countries like Japan, Spain, and Germany. With an increasing number of elderly dependents and not enough workers to replace them, their social support systems have become increasingly strained.

Even though in the last few decades there has been an increase in individual incomes, researchers have observed a negative correlation between the increased wealth and the number of children people choose to have. Sara Loo, as part of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), seeks to explore why people are choosing to have fewer children as their social and economic conditions change for the better.

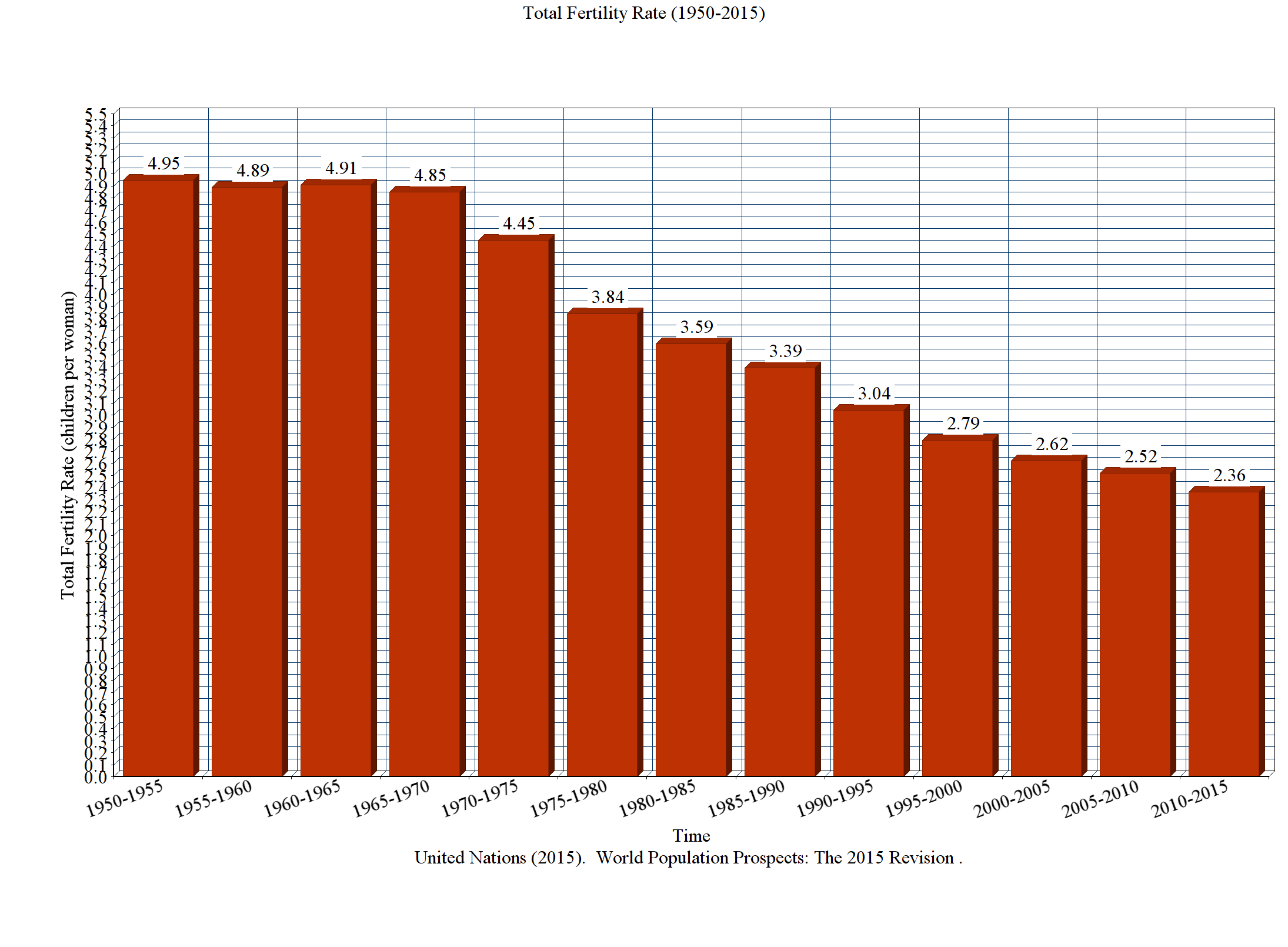

According to a report titled World Fertility Patterns 2015, global fertility levels have gone down from just above five children in 1950 to around 2.5 children per woman in 2015. In the figure below, ‘total fertility rate’ refers to the average number of children that are born to a woman over her lifetime.

It might seem counterintuitive that better living standards would be linked to decreased fertility. One way to explain it is through the lens of cultural evolution. Loo explains that culture is constantly changing – be it beliefs, knowledge, skills, or customs. This change is reflected in people’s day-to-day behaviors and affects their choices, both professional and personal. Importantly, beliefs and customs are acquired not only from people’s parents but are largely influenced by their peers – friends and colleagues.

One of the ways in which cultural evolution has affected fertility rates is resulting from the trade-off between the number of children and the quality of life that parents desire to give each of them, says Loo. As both men and women vie for well-paying jobs to attain a higher standard of living, and as they compete for such jobs based on their education, the resources parents invest into each child’s upbringing, including education and inheritance, are crucial. Even the time parents can give to their children becomes an expensive currency.

This makes for a highly competitive environment in which everyone is trying to achieve a higher status, in order to provide better opportunities for their children. When parents have fewer children, this means giving each of them a greater chance of achieving higher status.

Loo elaborates that as everyone competes to get their children to the top of the socioeconomic ladder, this necessitates a higher investment per child, both monetarily and otherwise. The theory of cultural evolution in this case thus predicts lowered fertility as competition for well-paying jobs intensifies with a country’s development.

However, it is not that such parental strategies apply equally to all segments of a population, says Evolution and Ecology Program Director Ulf Dieckmann, who is supervising Loo’s research at the institute over the summer. He explains that it is therefore helpful to look at fertility in relation to people’s socioeconomic status, instead of just looking at a population’s average fertility rate over time.

This can give telling insights. “In many pre-industrial societies, the rich had greater numbers of children, and if anybody had less than replacement-level fertility, it was the really poor people who could not afford to raise as many children. It was over time that this correlation changed from positive to negative when richer people decided to have fewer children: if they had too many children, they could not afford to invest as much per child as was needed to secure maintaining or raising the children’s socioeconomic status. This has led to a reversal of the traditional pattern: in developed societies, fertility has been shown to drop at high socioeconomic status,” says Dieckmann.

Complementing existing research on the fertility impacts of urbanization and of women’s education and liberation, Loo plans to explore how the aforementioned mechanisms of cultural evolution can explain the observed negative correlation between socioeconomic status and fertility. Her goal is to do so using a mathematical model that can account for both economic trends and cultural trends as two key processes influencing fertility rates.

About the researcher

Sara Loo is currently a third-year PhD candidate at the University of Sydney, Australia, where her research focuses on the evolution of uniquely human behaviors. Loo is working with the Evolution and Ecology Program at IIASA over the summer, with Professor Karl Sigmund and Program Director Ulf Dieckmann as her supervisors for the project.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.