Mar 7, 2018 | Energy & Climate

By Jessica Jewell, David McCollum, Johannes Emmerling, Christoph Bertram, David E.H.J. Gernaat, Volker Krey, Leonidas Paroussos, Loïc Berger, Kostas Fragkiadakis, Ilkka Keppo, Nawfal Saadi, Massimo Tavoni, Detlef van Vuuren, Vadim Vinichenko, Keywan Riahi

Our recent paper about our research on the effects of removing fossil fuel subsidies, published in Nature on February 8, 2018, generated a lot of comment and debate.

Here, we respond to three important themes raised in these comments. The first concerns the interpretation of our findings about the significance of subsidy removal for reducing CO2 emissions, the second concerns our approach to modeling and the data we used, and the third relates to policy options for more effective subsidy reform.

© Shutterstock / huyangshu

What are fossil fuel subsidies and why are they interesting for climate?

Fossil fuel subsidies are government interventions which decrease the price of fossil fuels below the market price. They can go to supporting the extraction of oil, gas, and coal (production subsidies) or making fuels cheaper for consumers (consumption subsidies) and amounted to over US$400 billion in 2015. There is a certain irony in that so many governments signed on to the Paris Agreement in 2015 yet in that same year many of those same governments spent so much money making fossil fuels cheaper.

How much would removing these subsidies help climate change mitigation efforts? How does it compare to what countries have already pledged to do for the climate under the Paris Agreement?

Comparing emission reductions from subsidy removal to key climate targets

Some commenters claim that it is already known that the effect of removing fossil fuel subsidies on emissions is limited. However, according to the authoritative Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC AR5), subsidy reform “can achieve significant emission reductions”. This view also is evident in the political sphere as: the Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform, a group of countries called fossil fuel subsidy reform “the missing piece of the puzzle in the fight against climate change”.

Our findings are that fossil fuel subsidy removal would lead to a 1-4% reduction in CO2 emissions in the energy sector by 2030 if oil prices stay low, and 1-5% if oil prices rise again, compared to the rise in emissions if subsidies are maintained, the baseline. It means that subsidy reform is a modest contribution to the global reductions required to achieve 2°C in a least-cost pathway, 27-57% by 2030.

More importantly, in our paper we compare emission reductions from subsidy removal not to this ideal goal, but to the actual targets pledged in the context of the Paris Agreement. Globally, Paris pledges would reduce emissions against the baseline in the energy sector by 9-13% in 2030 (under a moderate growth baseline) which is a larger reduction than fossil fuel subsidy removal would deliver. Under both the Paris climate pledges and fossil fuel subsidy phase-out global emissions would continue to rise whereas to achieve the 2°C target they should peak and eventually decline.

Identifying the regions with greatest impact

This global assessment is only part of our study. In addition, we show how the impacts of subsidy removal are different by region. In the major oil and gas exporting regions (Middle East and North Africa, Russia and its neighboring countries, and Latin America), removing fossil fuel subsidies lowers emissions by the same amount or more than these countries’ Paris pledges. Government revenues in these regions largely come from energy exports, which are squeezed by today’s low oil prices. Lowering government spending by removing subsidies is a real political opportunity to reduce emissions in these regions.

In other developing and emerging economies (India, China, the rest of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa), removing fossil fuel subsidies has less of an effect on emissions than these countries’ Paris pledges. In addition, the number of people who might be affected by subsidy removal in these regions is higher, simply because there are many more people living below the poverty line, for whom subsidies make the most difference. Taken together, these two findings frame one of our main results: that subsidy removal would be most useful for the climate precisely in the regions where it would affect fewer people living below the poverty line.

Data on subsidies

The second theme we would like to address relates to our data and modeling. Some commenters claimed that we underestimate both production subsidies and the effect of their removal.

According to data from the IEA and OECD only about 4% of subsidies are production subsidies. The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and Overseas Development Institute (ODI) publish an independent estimate based on their own definition and approach. Extrapolating to the global level, production subsidies would be about 14% in 2013 under their approach. We ran a sensitivity analysis using this higher production subsidies estimate. This did not change our findings (discussed in the Supplementary Information to our article).

Some commenters claimed that our study does not consider electricity production subsidies. This is also not true. We use the IEA data where power generation subsidies are captured in electricity subsidies. The SI discusses how each model integrates electricity subsidies.

There are other, fragmented estimates for electricity generation subsidies in individual countries, which generally take a different view of subsidies. For example, the recent report from IISD on Chinese subsidies to coal-fired power plants indicates that in 2014 and 2015, between 89% and 97% of these subsidies went to incentivize air pollution control equipment or closing inefficient plants. According to the same report, these subsidies also dropped by half from 2014 to 2015. Few governments would consider this as an environmentally-harmful subsidy, and removing such support will increase, not decrease emissions.

For our main analysis, we relied on IEA and OECD data for both production and consumption subsidies because these inventories are aligned with governments’ own estimates which are prepared as part of the G20 pledge to remove subsidies from 2009 reaffirmed in 2016. By using the same input data as governments and international organizations who are pledging or considering fossil fuel subsidy removal, we ensure the policy relevance of our results for these actors.

Estimating the effects of production subsidy removal

There were several comparisons of our results with those reported in a recent paper by Erickson et.al. in Nature Energy, which found that under the currently low oil prices, removing production subsidies in the US would make several oil fields unprofitable and eventually result in their closure. We find contrasting these two papers misleading as they ask very different research questions. Our study does not investigate how many oil fields in the US or elsewhere will become unprofitable after subsidy removal, but looks at the global effect of subsidy removal on emissions by taking into account trade in fossil fuels, the demand response and potential substitution of fuels and technologies. Erickson and his colleagues do not ask how much emissions will change as a result of closed oil fields. These are two very different questions.

Erickson and his colleagues compare the amount of carbon embedded in the oil reserves that may become unprofitable due to subsidy removal, to how much carbon the US would be allowed to emit under a stringent climate target. This creates an impression that they investigate the impact of removing oil production subsidies on US emissions. However, calculating the emission impact from removing oil production subsidies requires not only calculating the emissions embedded in foregone oil production, but also the possible emissions resulting from replacing this lost oil with other fuels, or changes in demand, for example if Americans choose to drive less if wells are closed, or if the US imports oil instead. We use these types of feedbacks in our models to calculate the emissions effects of subsidy removal (both consumption and production).

Redirecting subsidy funds

The third theme raised in the comments to our article was why we did not model redirecting subsidies to supporting renewable energy. While this is a very tempting question to ask from a climate perspective, and certainly one which we could do in our models, we did not consider it a realistic policy to be prioritized in our scenarios. In most countries fuel subsidies were introduced to support those on low incomes, although it is an inefficient way to do so. A state budget deficit and today’s low oil prices can often prompt successful subsidy reform. Indonesia for example recently expanded spending on infrastructure and programs to reduce poverty, while India introduced vouchers for cooking fuels. Iran, meanwhile introduced universal health coverage.

Fossil fuel subsidies do need reform

We would like to express our agreement with two comments, one from Ian Parry who wrote a commentary to our paper in Nature, and another from David Victor in his statement to Scientific American, that there are many reasons to reform fossil fuel subsidies other than emissions reductions. Our article does not cover these reasons and should not be interpreted as a comprehensive assessment of all aspects of subsidy removal.

We do however hope that our transparent and rigorous assessment of the effects of subsidy removal on CO2 emissions and energy use will support realistic and effective subsidy removal policies, and help in understanding the relative importance of a range of emission-reduction measures needed for achieving the ambitious long-term targets of the Paris Agreement.

As some commenters pointed out, we need all tools in the box to combat the enormous challenge of climate change. We fully agree. At the same time, we also believe in the need to understand how much each tool can do and where it can be most effective. This is exactly what our study answers.

Reference

Jewell J, McCollum, D Emmerling J, Bertram C, Gernaat DEHJ, Krey V, Paroussos L, Berger L, Fragkiadakis K, Keppo I, Saadi, N, Tavoni M, van Vuuren D, Vinichenko V, Riahi K (2018) Limited emission reductions from fuel subsidy removal except in energy exporting regions. Nature DOI: 10.1038/nature25467

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 22, 2018 | Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity

By Narasimha Rao, Project Leader of the Decent Living Energy (DLE) Project, IIASA Energy Program

Is there a conflict between reducing global income inequality and combating climate change? This seems like an odd question, given that these challenges have a lot in common. Raising the living standard of the poor for example, makes them resilient to climate impacts; less inequality can mean more political mobilization to establish climate policies; and changes in social norms away from material accumulation can reduce inequality and emissions. Academics have however been curious about the following phenomenon: In many countries, a dollar spent at higher income levels is less energy intensive than at lower income levels (known as “income elasticity of energy”). That is, rich people – although they consume much more in total – spend additional income on services or can afford energy-efficient goods, while the new middle class buy energy-intensive goods, like appliances and cars.

Many imagine China as a template for this type of fast growth. If globally significant, this effect would imply that growth that is more equitable would also be more emissions-intensive, and that we would have to pay particular attention to ensuring that climate policies reach the rising middle class in developing countries. While several studies have examined this phenomenon in specific countries, no one has examined its global significance. We set out to do that.

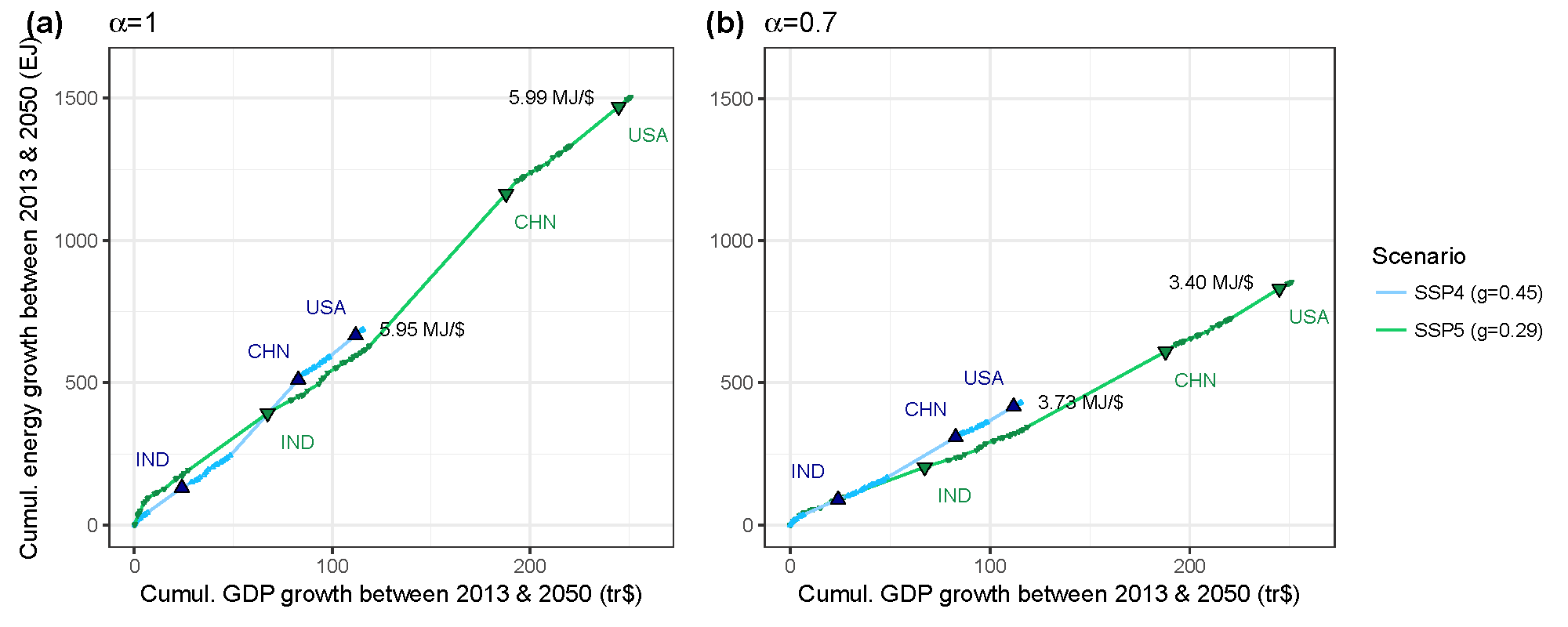

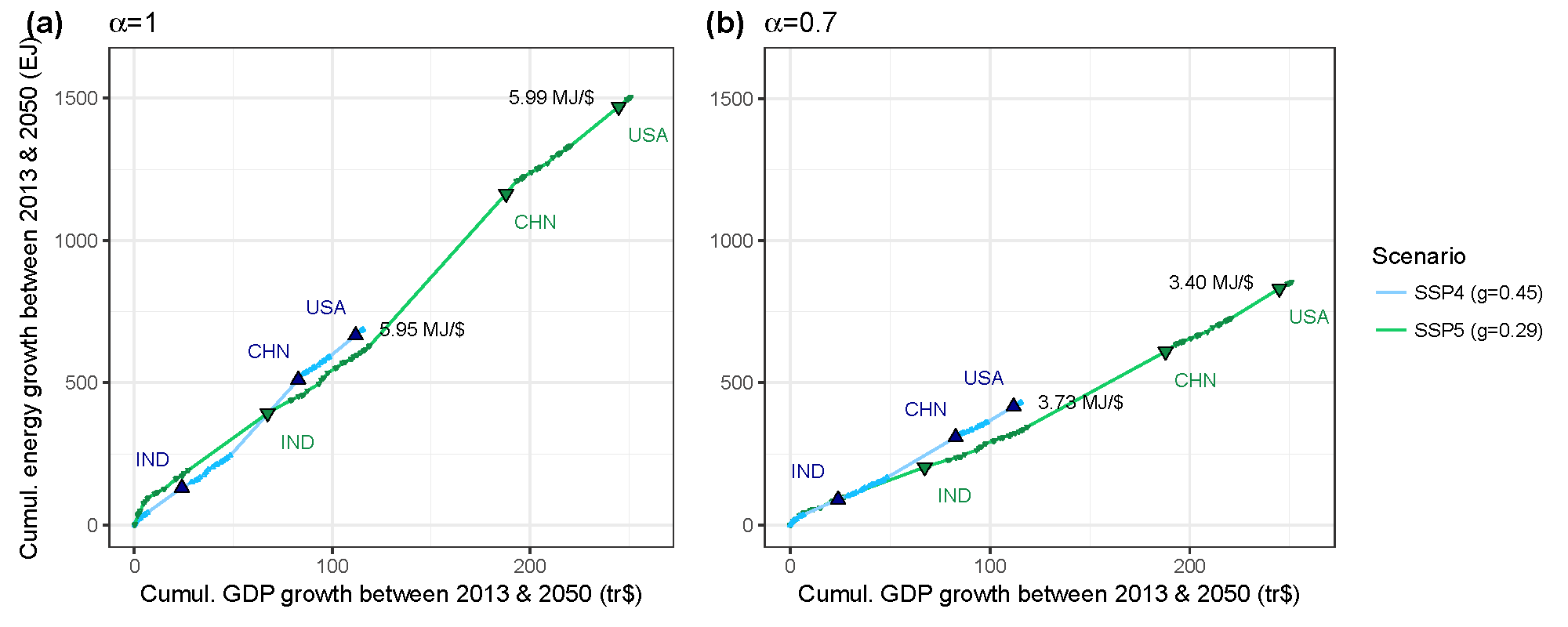

Energy intensity (MJ per $) lower in a high-growth, low inequality world (green line, Gini=0.29) compared to a low-growth, high inequality world (blue line, Gini=0.45). Gini reflects between-country inequality only.

Our analysis suggests that the energy-increasing effect of lowering inequality is more of a distraction than a concern. We compared scenarios of equitable and inequitable income growth, both within and between countries, assuming the most extreme manifestation of the income elasticity. Within any country, given the slow pace at which inequality typically evolves even with the most extreme known income elasticity and reduction in country inequality, greenhouse gas emissions would increase by less than 8% over a couple of decades. However, when one considers a more equitable distribution of growth between countries, global emissions growth may decrease when compared to growth that occurs in industrialized countries. This is because poorer countries have more potential for technological advancements that reduce the energy intensity of growth than richer countries do. That is, more income growth in poorer countries provides more opportunity for efficiency improvements that influence the emissions of very large populations. Furthermore, China is a poor model for poor countries at large, many of which have relatively low energy intensities, even today.

Climate stabilization at the level aspired to by the Paris Climate Agreement requires that we (i.e. the world) decarbonize to zero annual emissions around 2050, which means that even developing countries have to make aggressive strides towards integrating climate goals into development. Nevertheless, there is no sufficient basis for considering that equitable growth, and by implication the poor’s energy intensity, is part of the problem. To the contrary, the potential for co-benefits from equitable growth for climate change are enormous, but unfortunately under-explored, particularly in quantitative studies. Research should focus on quantifying the role of changing social norms – less consumerism, political mobilization, and other social changes that are typically associated with lower inequality – on reducing greenhouse gases.

Reference:

Rao, ND, Min J. Less global inequality can improve climate outcomes. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 2018;e513. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.513

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 15, 2018 | Data and Methods, Demography

By Dilek Yildiz, Wittgenstein Center for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW and WU), Vienna Institute of Demography, Austrian Academy of Sciences, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Social media offers a promising source of data for social science research that could provide insights into attitudes, behavior, social linkages and interactions between individuals. As of the third quarter of 2017, Twitter alone had on average 330 million active users per month. The magnitude and the richness of this data attract social scientists working in many different fields with topics studied ranging from extracting quantitative measures such as migration and unemployment, to more qualitative work such as looking at the footprint of second demographic transition (i.e., the shift from high to low fertility) and gender revolution. Although, the use of social media data for scientific research has increased rapidly in recent years, several questions remain unanswered. In a recent publication with Jo Munson, Agnese Vitali and Ramine Tinati from the University of Southampton, and Jennifer Holland from Erasmus University, Rotterdam, we investigated to what extent findings obtained with social media data are generalizable to broader populations, and what constitutes best practice for estimating demographic information from Twitter data.

A key issue when using this data source is that a sample selected from a social media platform differs from a sample used in standard statistical analysis. Usually, a sample is randomly selected according to a survey design so that information gathered from this sample can be used to make inferences about a general population (e.g., people living in Austria). However, despite the huge number of users, the information gathered from Twitter and the estimates produced are subject to bias due to its non-random, non-representative nature. Consistent with previous research conducted in the United States, we found that Twitter users are more likely than the general population to be young and male, and that Twitter penetration is highest in urban areas. In addition, the demographic characteristics of users, such as age and gender, are not always readily available. Consequently, despite its potential, deriving the demographic characteristics of social media users and dealing with the non-random, non-representative populations from which they are drawn represent challenges for social scientists.

Although previous research has explored methods for conducting demographic research using non-representative internet data, few studies mention or account for the bias and measurement error inherent in social media data. To fill this gap, we investigated best practice for estimating demographic information from Twitter users, and then attempted to reduce selection bias by calibrating the non-representative sample of Twitter users with a more reliable source.

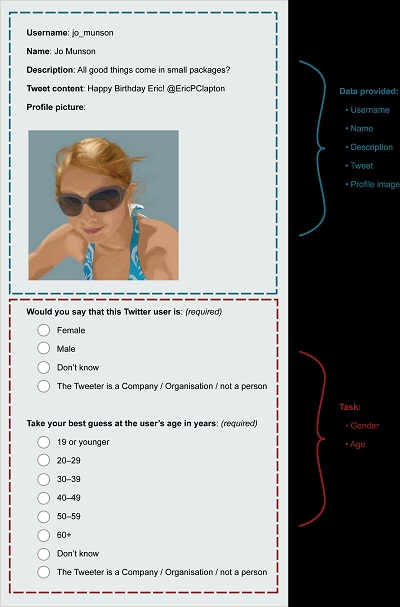

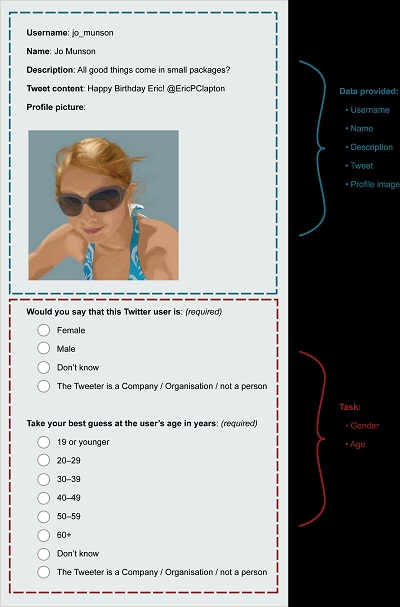

Exemplar of CrowdFlower task © Jo Munson.

We gathered information from 979,992 geo-located Tweets sent by 22,356 unique users in South-East England and estimated their demographic characteristics using the crowd-sourcing platform CrowdFlower and the image-recognition software Face++. Our results show that CrowdFlower estimates age more accurately than Face++, while both tools are highly reliable for estimating the sex of Twitter users.

To evaluate and reduce the selection bias, we ran a series of models and calibrated the non-representative sample of Twitter users with mid-year population estimates for South-East England from the UK Office of National Statistics. We then corrected the bias in age-, sex-, and location-specific population counts. This bias correction exercise shows promise for unbiased inference when using social media data and can be used to further reduce selection bias by including other sociodemographic variables of social media users such as ethnicity. By extending the modeling framework slightly to include an additional variable, which is only available through social media data, it is also possible to make unbiased inferences for broader populations by, for example, extracting the variable of interest from Tweets via text mining. Lastly, our methodology lends itself for use in the calculation of sample weights for Twitter users or Tweets. This means that a Twitter sample can be treated as an individual-level dataset for micro-level analysis (e.g., for measuring associations between variables obtained from Twitter data).

Reference:

Yildiz, D., Munson, J., Vitali, A., Tinati, R. and Holland, J.A. (2017). Using Twitter data for demographic research, Demographic Research, 37 (46): 1477-1514. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2017.37.46

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 30, 2017 | Environment, Food & Water, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

Two things are distinctly noticeable when you meet Cornelius Hirsch—a cheerful smile that rarely leaves his face and the spark in his eyes as he talks about issues close to his heart. The range is quite broad though—from politics and economics to electronic music.

Cornelius Hirsch

After finishing high school, Hirsch decided to travel and explore the world. This paid off quite well. It was during his travels, encompassing Hong Kong, New Zealand, and California, that Hirsch started taking a keen interest in economic and political systems. This sparked his curiosity and helped him decide that he wanted to take up economics for higher studies. Therefore, after completing his masters in agricultural economics, Hirsch applied for a position as a research associate at the Austrian Institute of Economic Research and enrolled in the PhD-program of the Vienna University of Economics and Business to study trade, globalization, and its impact on rural areas. Currently, he is looking at subsidies and tariffs for farmers and the agricultural sector at a global scale.

As part of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program at IIASA, Hirsch is digging a little deeper to analyze how foreign direct investments (FDI) in agricultural land operate. “Since 2000, the number of foreign land acquisitions have been growing—governmental or private players buy a lot of land in different countries to produce crops. I was interested in knowing why there are so many of these hotspots in the world— sub-Saharan Africa, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia—why are people investing in these areas?,” says Hirsch.

Farming in one of the large agricultural areas in Indonesia ©CIFOR I Flickr

Increased food demand from a growing world population is leading to an increased rate of investment in agriculture in regions with large stretches of fertile land. That these regions are largely rain-fed make them even more attractive for investors as they save the cost of expensive irrigation services. In fact, Hirsch argues that “the term land-grabbing is misleading. It should actually be water-grabbing as water is the foremost deciding factor—even more important than simply land abundance.”

Some researchers have found an interesting contrast between FDI in traditional sectors, such as manufacturing, and the ones in agricultural land. While investors in the former look for stable institutions and good governmental efficiency, FDI in land deals seems to target regions with less stable institutions. This positive relationship between corruption and FDI is completely counterintuitive. Hirsch says that one reason could be that “sometimes weaker institutions are easier to get through when it comes to such vast amount of lands. A lot of times these deals and contracts are oral and have no written proof—the contracts are not transparent anyway.”

For example in South Sudan, the land and soil conditions seem to be so good that investors aren’t deterred despite conflicts due to corrupt practices or inefficient government agencies.

One of the indigenous communities in Madagascar, a place which is vulnerable to land acquisitions © IamNotUnique I Flickr

One area that often goes unnoticed is the violation of land rights of indigenous communities. If a government body decides to sell land or give out production licenses to investors for leasing the land without consulting the actual community, it is only much later that the affected community finds out that their land has been given away. Left with no land and hence no source of livelihood, these communities are forced to migrate to urban areas.

A strain of concern enters his voice as Hirsch talks about the impact. “Land as big as two times the area of Ecuador has been sold off in the past—but it accounts for a tiny percentage of the global production area.” With rising incomes and greater consumption of meat, a lot of land is used to produce animal feed crops. “This is a very inefficient way of using land,” he says.

During the summer program at IIASA, Hirsch is generating data that will help him look at these deals in detail and analyze the main factors that are taken into consideration before finalizing a land deal. At the moment he is only able to give an overview of land-grabbing at the global level. With more data on the location of the deals he can look at the factors that influence these decisions in the first place such as the proximity between the two countries involved in agricultural investments and the size of their economies.

While there is always huge media coverage when a scandal about these land acquisitions comes out in the open, Hirsch seems determined to dig deeper and uncover the dynamics involved.

About the researcher

Cornelius Hirsch is a research associate at the Austrian Institute of Economics and Research (WIFO). At IIASA he is working under the supervision of Tamas Krisztin and Linda See in the Ecosystems Services and Management Program (ESM).

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 18, 2017 | Demography

By Valeria Bordone, University of Munich Department of Sociology and IIASA World Population Program

Everyone, consciously or unconsciously, formulates in their own mind a subjective survival probability– i.e., an estimate of how long they are going to live. This will affect decisions in different spheres of later life: retirement, investments, and healthy behaviors. Moreover, previous research has found that subjective survival probability is a good predictor of mortality. In fact, on average, people somehow know better than standard health measures the effect that their characteristics and their behavior have on life expectancy. It is however plausible not only to expect differences within the population in terms of survival, but also in the ability to predict their own survival.

(cc) roujo | Flickr

In a recent publication with Bruno Arpino from the University Pompeu Fabra and Sergei Scherbov from the Wittgenstein Centre (IIASA, VID/ÖAW, WU)., we presented for the first time joint analyses of the effect of smoking behavior and education on subjective survival probabilities and on the ability of survey respondents to predict their real survival, using longitudinal data on people aged 50-89 years old in the USA drawn from the Health and Retirement Study.

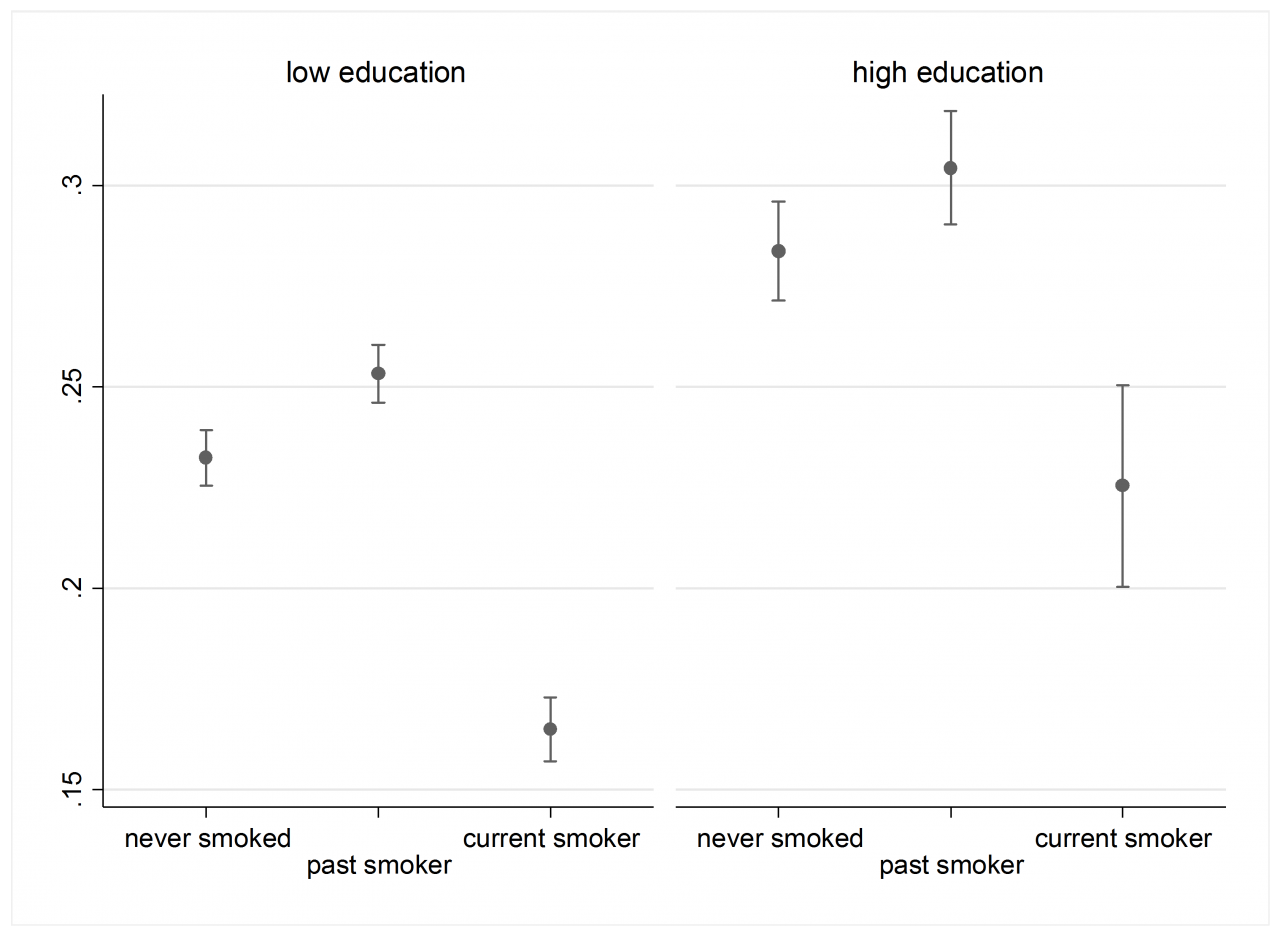

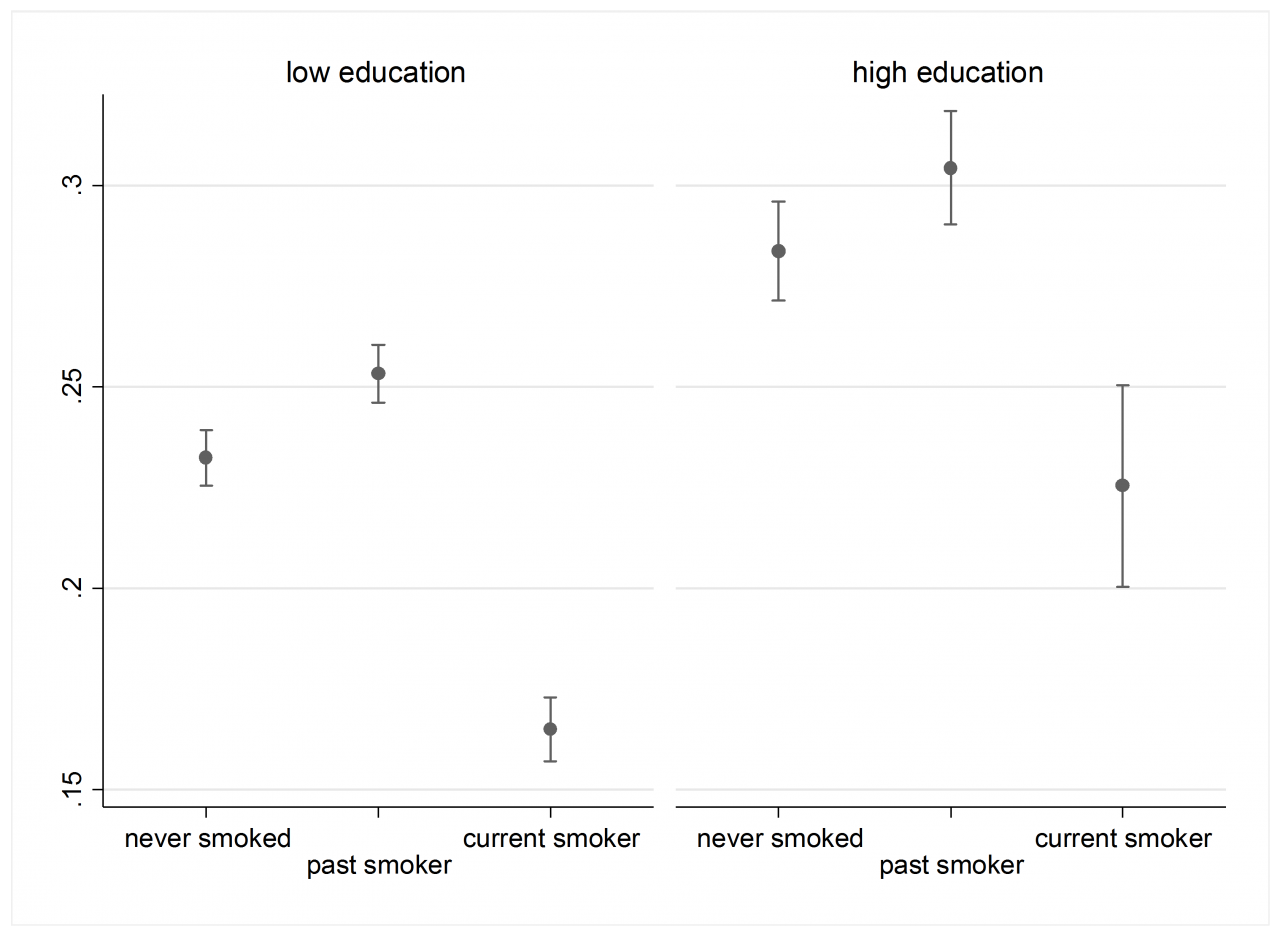

We found that, consistent with real mortality, smokers report the lowest subjective survival probabilities. Similarly, less educated people report lower subjective survival probabilities than higher education people. This is in line with the well-known positive correlation between education and life expectancy. However, despite being aware of their lower life expectancy as compared to non-smokers and past smokers, people currently smoking at the time of the survey tended to overestimate their survival probabilities. This holds especially for less educated people.

This graph shows the probability of correctly estimating the own survival probabilities with 95% confidence intervals, by smoking behavior and educational attainment. ©Arpino B, Bordone V, & Scherbov S (2017)

Our study suggests that in fact, education also plays an important role in shaping people’s ability to estimate their own survival probability. Whether or not they smoke, we found that more highly educated people are more likely to correctly predict their survival probabilities.

In view of the high proportion of the American population that consists of current or past smokers, a percentage that reached 77% in some male cohorts, our findings emphasize the need to disseminate more information about risks of smoking, specifically targeting people with less education.

By showing that smoking and education play together in determining how well people can assess the own survival potential, this study extends our understanding of the variability of subjective survival probabilities within a population. The fact that sub-groups within the population differently incorporate the effects of smoking into their assessment of survival probabilities may have important consequences for example on when people exit the labor market or whether they buy a life insurance, as individuals are likely to base their decisions also on their longevity expectations.

Policymakers can therefore draw some relevant conclusions from our study to design policies concerned with health and survivorship in later life. Despite the various anti-smoking campaigns and smoking restrictions, smokers may not be fully aware of the risks of smoking. In particular, educational groups seem to be differently exposed to the information that is disseminated to the public. Our study suggests that there is a need to target such information to less educated people, who are the most likely to underestimate the risks of smoking. Providing information on how survival probabilities vary by smoking behavior may not only reduce smoking but it may also increase individuals’ ability to assess their own survival.

(cc) Quinn Dombrowski | Flickr

Reference

Arpino B, Bordone V, & Scherbov S (2017). Smoking, Education and the Ability to Predict Own Survival Probabilities: An Observational Study on US Data. IIASA Working Paper. IIASA, Laxenburg, Austria: WP-17-012 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/14692]

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.