Nov 20, 2020 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

By Greg Davies-Jones, 2020 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Greg Davies-Jones sits down with 2020 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant Lisa Thalheimer to discuss how attribution science can play a leading role in addressing disaster displacement.

We live in the era of the greatest human movement in recorded history – there are more people on the move today than at any other point in our past. Despite the common misconception that most migrants cross borders, a lot of migration actually occurs internally. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, a staggering 72% of internal migration is linked to displacement due to natural hazards or extreme weather.

Pinpointing the finer details of how human mobility might evolve remains a complex undertaking. Contemporary migratory movements reflect the complex patterns of social and economic globalization – they flow in all directions and affect all countries in one way or another. It is clear that given the rising global average temperatures, natural hazards and extreme weather events will increase in frequency, intensity, and duration, adversely effecting many parts of the globe. A better understanding of how human-induced climate change influences disaster displacement will undoubtedly be essential in addressing future human mobility and informing the debate on climate and migration policies.

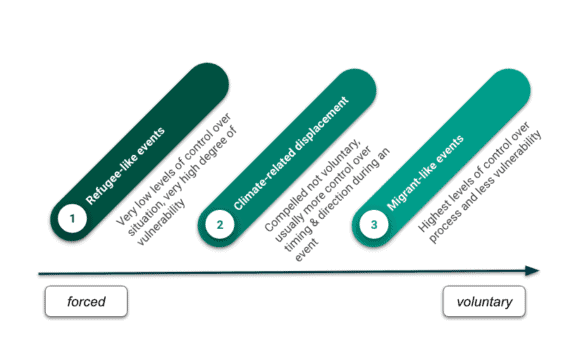

Figure: Climate-related displacement on an axis of forced to voluntary human mobility. Thalheimer (2020)

The focus of 2020 YSSP participant Lisa Thalheimer’s research is on internal displacement in East Africa, in particular, Somalia. As part of her YSSP project, Thalheimer hopes to determine whether, and to what extent, human-induced climate change altered the likelihood of extreme weather-related displacement in Somalia by conflating econometric methods and Probabilistic Event Attribution (PEA).

“Econometrics is essentially the application of statistical methods to quantify impacts and PEA is a way of examining to what extent extreme weather events can be linked with past man-made emissions. By combining the two methods we hope to quantify the ramifications of extreme weather and displacement in East Africa,” she explains.

This is no mean feat, as PEA itself is a relatively new science and many challenges still exist in the field of event attribution ̶ a field of research concerned with the process by which the causes of behavior and events can be explained. In this instance, the idea was to study each extreme weather event individually to determine if human-induced climate change may have added to the intensity or likelihood of the event occurring. PEA is a growing science within this field and relies on the availability of long-term meteorological observations and the reliability of climate model simulations. In terms of migration and the accompanying econometric methods, the complexity of this work is mainly in data capturing.

“The difficulty with migration data capturing is at the start – before you can capture anything, you must ascertain how the data is defined, as different countries define mobility in different ways. For instance, it could be time – where did you live one year ago as opposed to five years ago? That’s the first complexity. Then you must work out who collects data on who – in Europe, we have fundamental freedom of movement within the EU, so unless you file for residency, your movement is not recorded. Another complexity is because we want to see if climate change is part of the driver ̶ directly or indirectly. We need to know not just where people are now, but where they have been and where they came from, so we can match the climate with their movements. All of this highlights how difficult it is to carry out this type of analysis,” Thalheimer adds.

In Somalia, the team relied on previously collected forced migration data, for example, from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). These UNHCR datasets collected in Somalia were comprehensive and included not only origin and destination information but also a categorization of the primary reason for the displacement.

© Aleksandr Frolov | Dreamstime.com

The investigation homed in on one extreme weather case study in the region: The April 2020 heavy rainfall in Southern Ethiopia, which led to several severe flooding events in South Somalia. In this particular case, however, no appreciable connection could be made between human-induced climate change and the resultant displacement. Despite this somewhat chastening outcome, the achievement of this study is not proving a definitive attributable link between human-induced climate change and the April 2020 rainfall, but rather the construction of the adjustable attribution framework presented that can be applied directly to other events and displacement contexts.

As previously mentioned, there are, however, limitations to this novel methodology, especially in regions like Somalia that lack exhaustive observational weather and displacement data. According to Thalheimer, exploring ways of effectively applying this framework in countries vulnerable to climate change will be particularly important going forward.

“Event attribution studies do not usually form the basis of climate migration analysis, disaster risk reduction, or adaptation strategies. Yet, to respond appropriately to these impacts and affected populations, we must develop a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the nature of these impacts, as well as knowledge on how these might evolve over time. Event attribution is a tool we can employ to do this,” she concludes.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 10, 2020 | Air Pollution, China, Climate Change, Energy & Climate, Young Scientists

By Xu Wang, IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) alumnus and Assistant Professor at Beijing University of Technology and Pallav Purohit, researcher in the IIASA Air Quality and Greenhouse Gases Program.

Xu Wang and Pallav Purohit write about their recent study in which they found that accelerating the transition to climate-friendly and energy-efficient air conditioning in the Chinese residential building sector could expedite building a low-carbon society in China.

© Shao-chun Wang | Dreamstime.com

China saw the fastest growth worldwide in energy demand for space cooling in buildings over the last two decades, increasing at 13% per year since 2000 and reaching nearly 400 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity consumption in 2017. This growth was largely driven by increasing income and growing demand for thermal comfort. As a result, space cooling accounted for more than 10% of total electricity growth in China since 2010 and around 16% of peak electricity load in 2017. That share can reach as much as 50% of peak electricity demand on extremely hot days, as seen in recent summers. Cooling-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from electricity consumption consequently increased fivefold between 2000 and 2017, given the strong reliance on coal-fired power generation in China [1].

In our recent publication in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, we used a bottom-up modeling approach to predict the penetration rate of room air conditioners in the residential building sector of China at the provincial level, taking urban-rural heterogeneity into account. Our results reveal that increasing income, growing demand for thermal comfort, and warmer climatic conditions, could drive an increase in the stock of room air conditioners in China from 568 million units in 2015 to 997 million units in 2030, and 1.1 billion units in 2050. In urban China, room air conditioner ownership per 100 households is expected to increase from 114 units in 2015 to 219 units in 2030, and 225 units in 2050, with slow growth after 2040 due to the saturation of room air conditioners in the country’s urban households. Ownership of room air conditioners per 100 households in rural China could increase from 48 units in 2015 to 147 units in 2030 and 208 units in 2050 [2].

The Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer will help protect the climate by phasing down high global warming potential (GWP) hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are commonly used as refrigerants in cooling technologies [3]. Promoting energy efficiency of cooling technologies together with HFC phase-down under the amendment can significantly increase those climate co-benefits. It is in this context that we assessed the co-benefits associated with enhanced energy efficiency improvement of room air conditioners (e.g., using efficient compressors, heat exchangers, valves, etc.) and the adoption of low-GWP refrigerants in air conditioning systems. The annual electricity saving from switching to more efficient room air conditioners using low-GWP refrigerants is estimated at almost 1000 TWh in 2050 when taking account of the full technical energy efficiency potential. This is equivalent to approximately 4% of the expected total energy consumption in the Chinese building sector in 2050, or the avoidance of 284 new coal-fired power plants of 500 MW each.

Our results indicate that the cumulative greenhouse gas mitigation associated with both the electricity savings and the substitution of high-GWP refrigerants makes up 2.6% of total business-as-usual CO2 equivalent emissions in China over the period 2020 to 2050. Therefore, the transition towards the uptake of low-GWP refrigerants is as vital as the energy efficiency improvement of new room air conditioners, which can help and accelerate the ultimate objective of building a low-carbon society in China. The findings further show that reduced electricity consumption could mean lower air pollution emissions in the power sector, estimated at about 8.8% for sulfur dioxide (SO2), 9.4% for nitrogen oxides (NOx), and 9% for fine particulate matter (PM2.5) emissions by 2050 compared with a pre-Kigali baseline.

China can deliver significant energy savings and associated reductions in greenhouse gas and air pollution emissions in the building sector by developing and implementing a comprehensive national policy framework, including legislation and regulation, information programs, and incentives for industry. Energy efficiency and refrigerant standards for room air conditioning systems should be an integral part of such a framework. Training and awareness raising can also ensure proper installation, operation, and maintenance of air conditioning equipment and systems, and mandatory good practice with leakage control of the refrigerant during the use and end-of-life recovery. Improved data collection, research, and cooperation with manufacturers can equally help to identify emerging trends, technology needs, and energy efficiency opportunities that enable sustainable cooling.

References:

[1] IEA (2019). The Future of Cooling in China: Delivering on Action Plans for Sustainable Air Conditioning, International Energy agency (IEA), Paris.

[2] Wang X, Purohit P, Höglund Isaksson L, Zhang S, Fang H (2020). Co-benefits of energy-efficient air conditioners in the residential building sector of China, Environmental Science & Technology, 54 (20): 13217–13227 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/16823]

[3] Purohit P, Höglund-Isaksson L, Dulac J, Shah N, Wei M, Rafaj P, Schöpp W (2020). Electricity savings and greenhouse gas emission reductions from global phase-down of hydrofluorocarbons, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 20 (19): 11305-11327 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/16768]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA).

Aug 26, 2020 | Alumni, Climate Change, History, USA, Young Scientists

By Marcus Thomson, IIASA alumnus and a researcher at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), the University of California, Santa Barbara

IIASA alumnus Marcus Thomson explains how what we have learnt about prehistoric farming cultures can be used to provide useful insights on human societal responses to climate change.

The climate of the western half of the North American continent, between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific coastal region, is dry by European standards. The American Southwest, in particular, centered roughly on the intersection of the states of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, is predominantly desert between high mountain plateaus. It is, and has always been, a challenging environment for farmers. Yet the prehistoric Southwest was home to complex maize-based agricultural societies. In fact, until the 19th century growth of industrial cities like New York, the Southwest contained ruins of the largest buildings north of Mexico — and these had been abandoned centuries before the Spanish arrived in the Americas.

© Mudwalker | Dreamstime.com

For more than a century, researchers have pored over data, from proxies of paleo-environmental change, to historiographies collected by explorers, to archaeology and computational models of human occupation, and produced a detailed picture of the socio-environmental, economic, and climatic conditions that could explain why these sites were abandoned. While details vary in fine-grained analyses of the various sub-groupings of peoples in the region, the big picture is one of societal transformation in adapting to climate change.

Also important is just how the climate changed during the period, because similar dynamics are expected to emerge in the future as a consequence of global warming. European historians point to a medieval era with generally warmer mean annual temperatures. In the Southwestern United States however, which is more sensitive to changes in drought than temperature, the period between roughly AD 850 to 1350 is known as the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA). The warm, dry MCA was followed by a long stretch of increased changes in the availability of water, known as the Little Ice Age (LIA). More frequent “warm droughts” at the end of the MCA, and generally increasing changes in water resources at the onset of the LIA, is thought to be a good analogy for future conditions in western North America.

When I had the good fortune to visit IIASA as a participant of the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) in 2016, I worked with research scholars Juraj Balkovič and Tamás Krisztin to develop a model of ancient Fremont Native American maize. The Fremont were an ancient forager-farmer people who lived in the vicinity of modern Utah. We used a climate model reconstruction of the temperature and rainfall between AD 850 and 1450 to drive this maize crop model, and compared modeled crop yields against changes in radiocarbon-derived occupations – in other words, the information gathered from carbon dated artifacts that show that an area was occupied by a particular people – from a few archaeological areas in Utah.

© Galyna Andrushko | Dreamstime.com

Among our findings was that changes in local temperatures appeared to play a larger role in the lives, practices and habits of the people who lived there than changes in regional, long-term temperature conditions [1]. Later, while a researcher at IIASA myself, I returned to the subject with one of our coauthors, professor Glen MacDonald of the University of California, Los Angeles, using an expanded geographic range and a more sophisticated treatment of radiocarbon dated occupation likelihoods.

We used the climate model to reconstruct prehistoric maize growing season lengths and mean annual rainfall for Fremont sites. We found that the most populous and resilient Fremont communities were at sites with low-variability season lengths; and low populations coincided with, or followed, periods of variable season lengths. This study confirmed the important dependence on climate variability; and more importantly, our results are in line with others on modern smallholder farming contexts.

More details on our latest study [2] have just been published online in Environmental Research Letters (ERL). It will become part of an ERL special issue looking at societal resilience drawing lessons from the past 5000 years. Studies like these can give useful insights on human societal responses to climate change because these ancient civilizations are, in a sense, completed experiments with complex human-environmental systems. For decision makers, who must plan early to commit resources to offset the effects of future climate change on smallholder farmers in similarly drought-sensitive, marginally productive environments, these studies indicate that year-to-year climatic variability drives occupation change more than long-term temperature change.

References:

[1] Thomson MJ, Balkovič J, Krisztin T, & MacDonald GM (2019). Simulated impact of paleoclimate change on Fremont Native American maize farming in Utah, 850–1449 CE, using crop and climate models. Quaternary International, 507, pp.95-107 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15472]

[2] Thomson MJ, & MacDonald GM (In press). Climate and growing season variability impacted the intensity and distribution of Fremont maize farmers during and after the Medieval Climate Anomaly based on a statistically downscaled climate model. Environmental Research Letters.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 14, 2020 | Alumni, Postdoc, Sustainable Development, Women in Science

By Raquel Guimaraes, postdoc in the IIASA World Population Program, and Debbora Leip, an alumnus of the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program

IIASA researcher Raquel Guimaraes and former research assistant Debbora Leip encourage the support of the Cercedilla Manifesto, arguing that it is high time for the scientific community to take responsibility and set an example by making research meetings more sustainable.

© La Fabrika Pixel S.l. | Dreamstime.com

The research community widely agrees that strong action is needed to counteract the climate crisis that is currently taking place. Nevertheless, scientists regularly meet at conferences that are often far from sustainable. Problems range from participants flying to attend events, to unnecessary gadgets and gifts handed out at the meetings, and unsustainable catering at conference dinners. In light of the current public debate on environmental and social sustainability, we call on scientists to take a leading role in changing their work practices towards more sustainable habits, starting with research meetings.

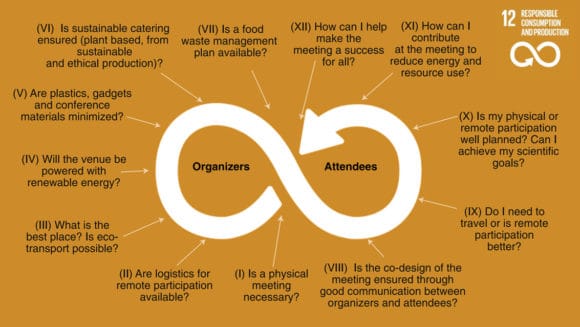

In April 2020, Alberto Sanz-Cobena and several colleagues published an article titled Research meetings must be more sustainable in Nature Foods. They presented the Cercedilla Manifesto with 12 sustainability decisions as guidelines for organizers and attendees of research meetings (see Figure 1). The starting point of the manifesto is to question whether a physical meeting is indeed necessary. If organizers decide that it is, there is still the question of whether each single attendee really needs to physically join the conference. Often, remote participation can be equally efficient if a technical solution is provided by the organizers. Furthermore, if a decision to conduct a physical meeting is taken, organizers have to consider what food will be served.

The authors state that excessive amounts of food and food waste are very common at meetings, which makes a change of mindset towards better food management very important, not only for climate change, but for many other environmental threats. In our opinion, this point has so far been neglected in public debate.

Given the urgency for climate change action and the need for individuals to play an active role – with research scientists taking the lead – we assert that it is urgent to start changing our habits and setting an example regarding environmental and social sustainability in research meetings. Indeed, many of us take it for granted that to meet and discuss our work, we must travel. Most attendees do not even question that unnecessary gadgets and gifts are distributed or that opulent dinners are provided.

We hope that the Cercedilla Manifesto will raise awareness about the fact that good scientific output often does not require a physical meeting by providing a conceptual framework for change in this regard. If we support the manifesto, we stand a chance to lower the barrier to dare deviating from currently applied practices. The 12-sustainability decisions were designed by specialists to serve as a reference for anybody who wishes to organize/attend a sustainable meeting.

In the current situation brought about by the global COVID-19 crisis, almost everybody has experienced that remote conferences are not only possible, but also efficient – sometimes even more so than a physical meeting would have been. First, it saves time in terms of travel. Second, it may be more inclusive by allowing people to attend, who would not have had the opportunity to join otherwise, be it for financial, family, or other reasons. In addition, remote meetings provide additional features, like a chat function that could add another discussion layer.

Of course, remote meetings also have their limitations: informal in-person meetings during coffee breaks, for example, can enhance networking and free discussions, and sometimes contribute significantly to a meeting’s outcome. Virtual meetings also face several other challenges, such as participation by attendees from different time zones, or poor internet connections. These issues could however easily be addressed by spreading the meeting over more days, in such a way that the need for attendance outside of acceptable time slots is minimized, and by investing saved traveling costs into better equipment.

Let us learn from this experience and not go ‘back to normal’ after the COVID-19 crisis. We should take this as an opportunity to speed up change and tackle the other global crisis of climate change!

You can find the petition at openpetition.eu/!cercedillamanifesto. We encourage you to share and support this initiative.

References:

Sanz-Cobena A, Alessandrini R, Bodirsky BL, Springmann M, Aguilera E, Amon B, Bartolini F, Geupel M, et al. (2020). Research meetings must be more sustainable. Nature Food 1, 187–189. DOI: 10.1038/s43016-020-0065-2

Frisch B, & Greene C (2020). What it takes to run a great virtual meeting. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/03/what-it-takes-to-run-a-great-virtual-meeting?ab=hero-subleft-3

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 5, 2020 | Alumni, Climate Change, Science and Policy, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Leila Niamir, post-doctoral researcher at the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), Germany and IIASA YSSP alumna.

© Cienpies Design Illustrations | Dreamstime

Weather patterns and events are changing and becoming more extreme, sea levels are rising, and greenhouse gas emissions are now at their highest levels in history[1]. Climate change is affecting every individual in every city on every continent. It imposes adverse impact on people, communities, and countries, disrupting regional and national economies.

Climate change mitigation refers to efforts to reduce or prevent emissions of greenhouse gases to limit the magnitude of long-term climate change. Human consumption, in combination with a growing population, contributes to climate change by increasing the rate of greenhouse gas emissions. Over the last decade, instigated by the Paris Agreement, the efforts to limit global warming have been expanding. Significant attention is being devoted to new energy technologies on both the production and consumption sides, however, changes in individual behavior and management practices as part of the mitigation strategy are often neglected[2]. This might derive from the complex nature of human which makes explaining and affecting human behavior a difficult task. As a result, quantitative tools to assess household emissions, considering the diversity of behaviors and a variety of psychological and social factors influencing them beyond purely economic considerations, are scarce. Policymakers would benefit from reliable decision supporting tools that explore the interaction of economic decision-making and behavioral heterogeneity in households behavioral and lifestyle changes, when testing climate mitigation policies (e.g. carbon pricing, subsidies)[3].

To address this issue, during my PhD research I studied the potential of behavioral changes among heterogeneous households regarding energy use and their role in mitigating climate change. By designing and conducting comprehensive household surveys, it was explored how individuals choose to change their energy behaviour and what factors trigger or inhibit these choices[4]. Decision support tools are designed to study large-scale regional effects of individual actions, and to explore how they may change over time and space. The model explicitly treats behavioral triggers and barriers at the individual level, assuming that energy use decision making is a multi-stage process. This theoretically and empirically grounded simulation model offers policymakers ways to explore various policy portfolios by running diverse micro and macro scenarios.

This model was further developed during my collaboration with the IIASA the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), to estimate macro impacts of individuals’ energy behavioral changes on carbon emissions[5]. Within this research, we illustrate that individual energy behavior, especially when amplified through social context, shapes energy demand and, consequently, carbon emissions. Our results show that residential energy demand is strongly linked to personal and social norms. When assessing the cumulative impacts of these behavioral processes, we quantify individual and combined effects of social dynamics and of carbon pricing on individual energy efficiency and on the aggregated regional energy demand and emissions.

In summary, mitigating climate change requires massive worldwide efforts and strong involvement of regions, cities, businesses and individuals, in addition to the commitments at the national levels. We should always keep in mind that every single behavior matters. In the transition to a sustainable and resilient society, we –as individuals- are more than just consumers.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

[1] Climate Action– United Nations Sustainable Development Goals https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change/

[2] Creutzig, F., et al. (2018). Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nature Climate Change 8, 268-271; Grubler, A., et al. (2018). A low energy demand scenario for meeting the 1.5 degrees C target and sustainable development goals without negative emission technologies. Nature Energy 3, 515-527; Creutzig, F., et al. (2016). Beyond Technology: Demand-Side Solutions for Climate Change Mitigation. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, Vol 41 41, 173-198

[3] Niamir, L. (2019). Behavioural Climate Change Mitigation: from individual energy choices to demand-side potential (University of Twente); Creutzig, F., et al. (2018). Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nature Climate Change 8, 268-271; Niamir, L., et al. (2018). Transition to low-carbon economy: Assessing cumulative impacts of individual behavioural changes. Energy Policy, 118; Stern N. Economics: Current climate models are grossly misleading. Nature 530(7591):407–9.

[4] Niamir, L. et al. (2020). Demand-side solutions for climate mitigation: Bottom-up drivers of household energy behaviour change in the Netherlands and Spain. Energy Research & Social Science, 62, 101356.

[5] The results of this collaboration was presented at Impacts World 2017 and won the best prize, and also published at Climatic Change Journal.

You must be logged in to post a comment.