May 27, 2021 | Environment, IIASA Network, Sustainable Development

By Michel Spiro, President of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) and President of the Steering Committee for the proclamation of the International Year of Basic Sciences for Sustainable Development in 2022 (IYBSSD 2022)

A consortium of international scientific unions and scientific organizations’ plans to declare 2022 the International Year of Basic Sciences for Sustainable Development are underway. Michael Spiro makes the case for why the world needs this now more than at any time in the past.

© Dmytro Tolokonov | Dreamstime.com

For almost a year and a half now, the world has been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. But how much worse could the situation have been without the progress and results produced for decades, even centuries, by curiosity-driven scientific research?

We deplore the many deaths due to COVID-19, and the future is still very uncertain, especially with the detection of new variants, some of which are spreading more quickly. But how could we have known that the infection was caused by a virus, what this virus looks like and what its genetic sequence and variations are without basic research?

Viruses were discovered at the beginning of the 20th century, thanks to the work of Frederick Twort, Félix d’Hérelle, and many others. The first electron microscope was built in the 1930s by Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll; and DNA sequencing began in the mid-1970s, notably with research by the groups of Frederick Sanger and Walter Gilbert.

Such a list could of course go on and on, with basic research at the root of countless tests, treatments, vaccines, and epidemiological modeling exercises. We even owe high-speed, long-distance communications, which allow us to coordinate the fight against the pandemic and reduce interruptions in education, economic activities, and even the practice of science, to the discovery and study of electromagnetic waves and optic fibers during the 19th century, and the development of algorithms and computers codes during the 20th century. The COVID-19 pandemic is a reminder (so harsh and brutal that we would have preferred to have been spared) of how much we rely on the continuous development of basic sciences for a balanced, sustainable, and inclusive development of the planet.

On many other issues, basic sciences have an important contribution to make to progress towards a sustainable world for all, as outlined in Agenda 2030 and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals, adopted in September 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly. They provide the essential means to address major challenges such as universal access to food, energy, and sanitation. They enable us to understand the impacts of the nearly eight billion people currently living on the planet, on the climate, life on Earth, and on aquatic environments, and to act to limit and reduce these impacts.

Indeed, unlike our use of natural resources, the development of the basic sciences is sustainable par excellence. From generation to generation, it builds up a reservoir of knowledge that subsequent generations can use to apply to the problems they will face, which we may not even know about today.

The International Year of Basic Sciences for Sustainable Development (IYBSSD) will focus on these links between basic sciences and the Sustainable Development Goals. It is proposed to be organized in 2022 by a consortium of international scientific unions and scientific organizations* led by the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IIUPAP) with the recommendation of a resolution voted by the UNESCO General Conference during its 40th session in 2019. Over 50 national and international science academies and learned societies and around 30 Nobel Prize laureates and Fields Medalists also support this initiative. The Dominican Republic has agreed to propose a resolution for the promulgation of the IYBSSD during the 76th session of the United Nations General Assembly, beginning in September 2021.

The International Year of Basic Sciences for Sustainable Development (IYBSSD) will focus on these links between basic sciences and the Sustainable Development Goals. It is proposed to be organized in 2022 by a consortium of international scientific unions and scientific organizations* led by the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IIUPAP) with the recommendation of a resolution voted by the UNESCO General Conference during its 40th session in 2019. Over 50 national and international science academies and learned societies and around 30 Nobel Prize laureates and Fields Medalists also support this initiative. The Dominican Republic has agreed to propose a resolution for the promulgation of the IYBSSD during the 76th session of the United Nations General Assembly, beginning in September 2021.

We very much hope that scientists, and all people interested in basic science, will mobilize around the planet and take this opportunity to convince all stakeholders – the general public, teachers, company managers, and policymakers – that through a basic understanding of nature, inclusive (especially by empowering more women) and collaborative well-informed actions will be more effective for the global common interest. As IIASA is one of the consortium’s founding partners, we especially invite all IIASA scientists, alumni, and colleagues they are collaborating with to create or join national IYBSSD 2022 committees to organize events and activities during this international year.

More information, as well as communication material, can be found at www.iybssd2022.org. This will also be shared through social media accounts (look for @iybssd2022 on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram). You are also invited to subscribe to the Newsletter here.

* Consortium members

The International Union of Crystallography (IUCr); the International Mineralogical Association (IMA); the International Mathematical Union (IMU); the International Union of Biological Sciences (IUBS); the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG); the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC); the International Union of History and Philosophy of Science and Technology (IUHPST); the International Union of Materials Research Societies (IUMRS); the International Union for Vacuum Science, Technique, and Applications (IUVSTA); the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN); the French Research Institute for Development (IRD); the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA); the European Physical Society (EPS); the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR); the Nuclear Physics European Collaboration Committee (NuPECC); the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP); the International Science Council (ISC); Rencontres du Vietnam; the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR); the Square Kilometre Array Organization (SKAO); and SESAME (Synchrotron-light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East).

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 12, 2021 | Poverty & Equity, Risk and resilience, Sustainable Development

by Viktor Roezer | Swenja Surminski | Finn Laurien | Colin McQuistan | Reinhard Mechler | Anna Svensson

Disaster Risk Reduction investments bring a wide variety of benefits, including economic, ecological, and social, but in practice these multiple resilience dividends are often not included in investment appraisals or are not recognized by those making funding decisions. How do we change this?

Research led by the London School of Economics and Political Science with IIASA and Practical Action published in the Working Paper Multiple resilience dividends at the community level: A comparative study on disaster risk reduction interventions in different countries highlights the need for an integrated decision-making framework to overcome the challenges.

The negative effects of disasters on people and communities are varied and far reaching, and will only get worse as climate change make floods and other natural hazards more frequent, severe, and unpredictable. Disasters lead to loss of lives, assets, and livelihoods, they undermine or destroy development progress. Since 2000 climate related hazards have caused $2.2 trillion of losses and damages and have affected approximately 3.9 billion people globally.

With investments in disaster risk reduction (DRR), where community resilience is enhanced these negative impacts can be reduced and savings can be made. It’s more cost effective to invest in pre-event resilience than post-event response and recovery.

So why is disaster risk reduction so difficult to finance?

The problem with estimating the direct benefit of disaster risk reduction interventions is that you only see the benefits when an event which would otherwise have turned into a disaster occurs and is successfully mitigated.

This makes cost-benefit analysis and other decision-making methods difficult to carry out, and makes the costs of doing something more aligned to the probability of the event, rather than the lives and economic costs saved, thus changes to policy and practice are slow to materialize.

What are the multiple dividends of resilience?

The multiple dividends of resilience refer to positive socioeconomic outcomes generated by, and co-benefits of, an intervention beyond, and in addition to, risk reduction.

It’s an approach aimed at making DRR investments more attractive as the multiple dividends of an investment may help identify win-win-win situations (as well as trade-offs), even if no hazard event occurs. Co-benefits can be intended, or unintended.

As framed by the Triple Resilience Dividend concept these benefits can be divided into three categories:

1. The avoided losses and damages in case of a disaster

For example, how bio-dykes in Nepal prevent river bank erosion, which reduces the risk of flooding, and associated sand deposits that ruin the fertility of agricultural land.

2. The economic potential of a community that is unlocked through the intervention

This includes ecosystem-based adaptation solutions in Vietnam where mangrove plantations create new habitats for fish, leading to improved livelihood opportunities for those making their living from fishing.

3. Other development co-benefits

Transition to solar stoves in rural Afghanistan does not only protect natural capitals from degradation, but also empowers women and girls, reduces in-house smog pollution, and fosters technological innovations.

Rongali next to his community’s bio-dyke. Photo by Sanjib Chaudhary, Practical Action.

What are the challenges?

The triple resilience dividend approach is often linked to new and innovative solutions like ecosystem based adaptation, where the benefits can be wider, but when and how they will materialize is more uncertain than with traditional, hard infrastructure solutions.

Although many developing countries have policies that align DRR, climate change adaptation, and sustainable development, sadly, in practice, local decision makers assume that multiple resilience dividends will only accumulate over the long term. This often leads them to select traditional, hard infrastructure solutions that offer quick and more visible protection.

We need more success stories. Pilot interventions can be shared and shown to community members and decision makers to overcome their skepticism but this require better and more comprehensive evidence than we have today.

We also lack decision-making frameworks that can include and monitor multiple resilience dividends. Frameworks that support planners as they navigate the decision-making process, and help generate the evidence needed.

Community members in the Peruvian Andes working at a local tree nursery. Photo by Giorgio Madueño , Practical Action

How do we overcome these challenges?

The solution suggested in Multiple resilience dividends at the community level: A comparative study on disaster risk reduction interventions in different countries is an integrated decision-making framework that allows to systematically include, appraise, implement, and evaluate individual resilience dividends at each stage of the decision-making process.

Application and relevance matters.

As we suggest, instead of maximizing resilience dividends based on a specific, one dimensional, metric (e.g., monetary benefits) decision-making approaches need to identify those dividends that are most needed and demanded by the community and the solutions, novel or local in nature, best suited to generate these.

A structured approach in combination with participatory decision making allows for a tailored approach where community buy-in is achieved by prioritizing the resilience dividend(s) that matter most to them, while at the same time contributing to the evidence base for multiple resilience dividends.

This is urgently needed to highlight the fundamental challenges with the existing planning and decision-making system and therefore generate demand to deliver more effective solutions at scale.

Cleaning waste from river in Penjaringan Urban Village, Jakarta, Indonesia. Photo by Piva Bell, Mercy Corps.

Read the working paper this blog is based on here.

This blog post first appeared on the Flood Resilience Portal. Read the original post here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 5, 2021 | Climate Change, Poverty & Equity, Risk and resilience

By Julian Joseph, research assistant in the Water Security Research Group

Julian Joseph explains the concept of the triple dividend of disaster risk reduction investments based on the application of a novel economic model applied to a case study undertaken in Tanzania and Zambia.

What are the benefits of Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) investments such as dams and the introduction of drought-resistant crops in agriculture for an economy? They are threefold and called the “triple dividend” of DRR investments. The first dividend comprises the direct effects of DRR investments, which limit damage to houses, infrastructure, and other physical assets and prevent death and injury. The second dividend unlocks the economic potential of an economy because risk reduction drives people and businesses to invest more, as they expect less of what they invest in to be destroyed by disasters, while the third dividend is comprised of development co-benefits through other uses the investments provide.

© Gerrit Rautenbach | Dreamstime.com

Using a new macroeconomic model called DYNAMMICs, my colleagues and I have found that there is often a significant growth effect for the economy attached to investing in mitigation measures like dams and drought resistant crops, which is commonly underestimated in traditional models. One reason for this is the focus of other models on only the first, direct dividend. We specifically looked into the examples of Tanzania and Zambia, which show that governments and other stakeholders in developing countries can spur economic growth by investing in DRR measures, thus increasing future earnings and creating a safe environment for investments into other economic activities.

In Tanzania and Zambia, floods affect tens of thousands of people each year (on average 45,000 or .08% of the population in Tanzania and 20,000 or .11% of the population in Zambia). Droughts have more widespread consequences and already affect 11.8% of the population in Tanzania and 19% of Zambians who often lose all or parts of their harvest. This poses an imminent threat to food security in countries where substantial shares of the population rely on subsistence farming as their primary source of income. Given the effects of climate change, these numbers and their ramifications are bound to become ever more pressing issues. However, policymakers, institutions, enterprises, and individuals tend to underinvest in adaption measures.

A promising avenue for demonstrating the potential of DRR investments is offered by including all economic growth effects they invoke into policy analysis, thus showing that besides risk reduction and post-disaster mitigation of destruction, investing in DRR measures can help countries achieve many of their other development goals as well.

We tend to only think of the first dividend of DRR investments, the direct effects of which stop people from being immediately affected by disasters. In the case of Tanzania and Zambia, we examined, among others, the benefits of constructing additional dams. The direct benefits of dams lie in the safeguarding of livelihoods, infrastructure, housing, and agricultural production. These are seen as the first dividend, called the ex-post damage mitigation effect. There are however also additional co-benefits.

In both Tanzania and Zambia, large shares of the population are heavily dependent on agriculture, which makes the introduction of drought-resistant crop varieties such an additional benefit. These crop varieties do not only help farmers preserve their yields in times of disastrous droughts, but additionally support farmers by generating higher yields, even in the absence of disaster. This effect is boosted by the lowered risk for the loss of crops, which spurs investment into farming activities and inputs. Farmers who do not fear losing their entire harvest can, and generally will, invest more into the production of this crop – an example of the second type of dividend, the ex-ante risk reduction effect. This type of economically beneficial effect materializes regardless of the onset of disaster.

The same is true for the third type of dividend, the co-benefit production expansion effect, which is especially relevant for the advantages of dams. The power generation capability of dams, leads to much larger economic gains than the two other dividends combined. In countries such as those at hand with frequent power cuts and comparably low levels of electrification, especially in rural areas, the additional electricity generated can lead to particularly pronounced positive effects by supplying economic actors with access to power. In other scenarios, the provision of ecosystem services is also an important effect falling into this category.

The results we obtained using the DYNAMMICs model are promising: Constructing only two additional dams leads to a 0.3% increase of GDP growth in Tanzania for the next 30 years (0.2% in Zambia) with results largely (97%) driven by the co-benefit production expansion effect. Similarly, the introduction of drought resistant crops and exposure management (i.e., land use restrictions) significantly boost economic growth perspectives. Finally, introducing insurance is a driver for a reduction in the variance of GDP growth, which helps to reduce uncertainty for everyone in the economy. Modeling in such a fashion is therefore an important means of weighing policy options for DRR against each other and for determining optimal levels of investment.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 18, 2021 | Austria, Climate, Climate Change, Communication, Education, Health

By Thomas Schinko, Acting Research Group Leader, Equity and Justice Research Group

Thomas Schinko introduces an innovative and transdisciplinary peer-to-peer training program.

What do we want – climate justice! When do we want it – now! The recent emergence of youth-led, social climate movements like #FridaysForFuture (#FFF), the Sunrise Movement, and Extinction Rebellion has reemphasized that at the heart of many – if not all – grand global challenges of our time, lie aspects of social and environmental justice. With a novel peer-to-peer education format, embedded in a transdisciplinary research project, the Austrian climate change research community responds to the call that unites these otherwise diverse movements: “Listen to the Science!”

The climate crisis raises several issues of justice, which include (but are not limited to) the following dimensions: First, intragenerational climate justice addresses the fair distribution of costs and benefits associated with climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as the rectification of damage caused by residual climate change impacts between present generations. Second, intergenerational justice focuses on the distribution of benefits and costs from climate change between present and future generations. Third, procedural justice asks for fair processes, namely that institutions allow all interested and affected actors to advance their claims while co-creating a low-carbon future. Movements like #FFF maneuver at the intersection of those three forms of climate justice when calling on policy- and decision makers to urgently take climate action, since “there is no planet B”.

Along with the emergence of these youth-led social climate movements came an increasing demand for the expertise of scientists working in the fields of climate change and sustainability research. To support #FFF’s claims with the best available scientific evidence, a group of German, Austrian, and Swiss scientists came together in early 2019 as Scientists for Future. Since then, requests from students, teachers, and policy and decision makers for researchers to engage with the younger generation have soared, also in Austria. Individual researchers like me have not been able to respond to all these requests at the extent we would have liked to.

In this situation of high demand for scientific support, the Climate Change Center Austria (CCCA) and The Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research (BMBWF) have put their heads together and established a transdisciplinary research project – makingAchange. By engaging early on with our potential end users – Austrian school students – a truly transdisciplinary team of researchers as well as practitioners in youth participation and education (the association “Welt der Kinder”) has co-developed this novel peer-to-peer curriculum. The training program, which runs over a full school year, sets out to provide the students not only with solid scientific facts but also with soft skills that are needed for passing on this knowledge and for building up their own climate initiatives in their schools and municipalities. One of the key aims is to provide solid scientific support while not overburdening the younger generation who often tend to put too high demands on themselves.

Establishing scientific facts about climate change and offering scientific projections of future change on its own does not drive political and societal change. Truly inter- and transdisciplinary research is needed to support the complex transformation towards a sustainable society and the integration of novel, bottom-up civil society initiatives with top-down policy- and decision making. Engaging multiple actors with their alternative problem frames and aspirations for sustainable futures is now recognized as essential for effective governance processes, and ultimately for robust policy implementation.

Also, in the context of makingAchange it is not sufficient to communicate science to students in order to generate real-world impact in terms of leading our societies onto low-carbon development pathways. What is additionally needed, is to provide them with complementary personal and social skills for enhancing their perceived self-efficacy and response efficacy, which is crucial for eventually translating their knowledge into real climate action in their respective spheres of influence.

Recent insights from a medical health assessment of the COVID-19 related lockdowns on childhood mental health in the UK have shown that we are engaging in an already highly fragile environment. In addition, a recent representative study for Austria has shown that the pandemic is becoming a psychological burden. The study authors are particularly concerned about young people; more than half of young Austrians are already showing symptoms of depression. Hence, we must engage very carefully with the makingAchange students when discussing the drivers and potential impacts of the climate crises. Particularly since some of them are quite well informed about research, which has shown (by using a statistical approach) that our chances of achieving the 1.5 to 2°C target stipulated in the Paris Agreement are now probably lower than 5%. Another example of such alarming research insights comes in the form of a 2020 report by the World Meteorological Organization, which warns that there is a 24% chance that global average temperatures could already surpass the 1.5°C mark in the next five years.

Zoom group picture taken at the end of the second online makingAchange workshop for Austrian school students. Copyright: makingAchange

The first makingAchange activities and workshops have now taken place – due to the COVID-19 regulations in an online format, which added further complexity to this transdisciplinary research project. Nevertheless, we were able to discuss some of the hot topics that the young people were curious about, such as the natural science foundations of the climate crisis, climate justice, or a healthy and sustainable diet. At the same time, we provided our students with skills to further transmit this knowledge and to take climate action in their everyday live – such as a climate friendly Christmas celebration in 2020. The school student’s lively engagement in these sessions as well as the overall positive (anonymous) feedback has proven that we are on the right track.

The role of science is changing fast from “advisor” to “partner” in civil society, policymaking, and decision making. By doing so, scientists can play an important, active role in implementing the desperately needed social-ecological transformation of our society without becoming policy prescriptive. With the makingAchange project, we are actively engaging in this transformational process – currently only in Austria but with high ambitions to scale-out this novel peer-to-peer format to other geographical and cultural contexts.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 2, 2021 | Environment, Poverty & Equity, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

By Prakash Khadka, IIASA Guest Research Assistant and Wei Liu, Guest Research Scholar in the IIASA Equity and Justice Research Group

Prakash Khadka and Wei Liu explain how unbridled, unplanned infrastructure expansion in Nepal is increasing the risk of landslides.

Worldwide, mountains cover a quarter of total land area and are home to 12% of the world’s population, most of whom live in developing countries. Overpopulation and the unsustainable use of these fragile landscapes often result in a vicious cycle of natural disaster and poverty. Protecting, restoring, and sustainably using mountain landscapes is an important component of Sustainable Development Goal 15 ̶ Life on Land ̶ and the key is to strike a balance between development and disaster risk management.

Nepal is among the world’s most mountainous countries and faces the daunting challenge of landslides and flood risk. Landslide events and fatalities have been increasing dramatically in the country due to a complex combination of earthquakes, climate change, and land use, especially the construction of informal roads that destabilize slopes during the monsoon.

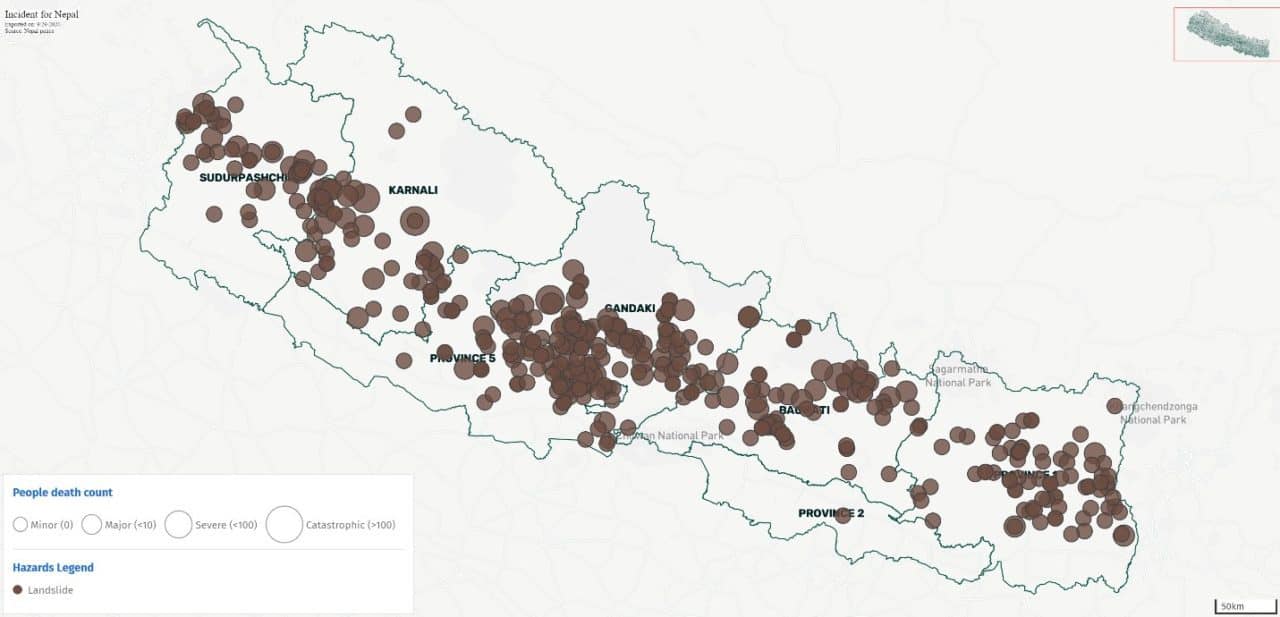

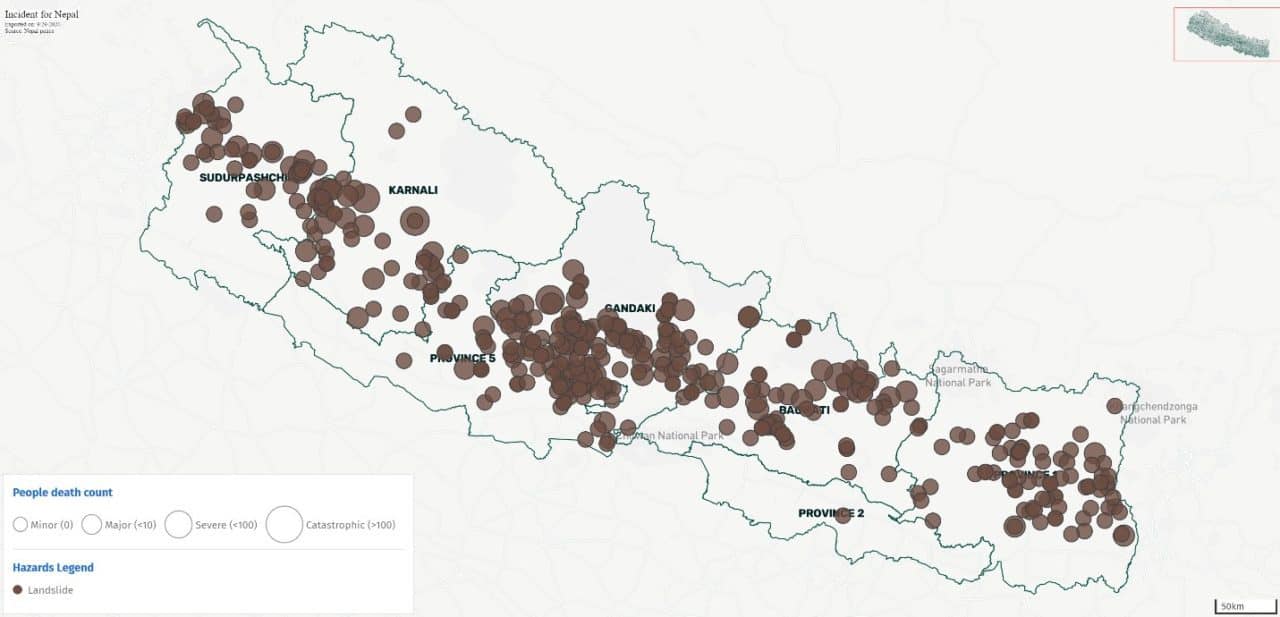

According to Nepal government data, 476 incidents of landslides and 293 fatalities were recorded during the 2020 monsoon season – the highest number in the last ten years, mostly triggered by high-intensity rainfall – a trend which is increasing due to climate variations. According to one study, by mid-July 2020, the number of fatal landslides for the year had already exceeded the average annual total for 2004–2019.

Figure 1: A map of landslide events in Nepal from June to September 2020. Source: bipadportal.gov.np

Landslides are not a new phenomenon in the country where hills and mountains cover nearly 83% of the total land area. While being destructive, landslides are complex natural processes of land development. The Gangetic plain, situated in the foothills of the Himalayas, was formed by the great Himalayan river system to which soil is continually added by landslides and deposited at the base by rivers. Mountain land changes via natural geo-tectonic and ecological processes has been happening for millions of years, but fast population growth and climate change in recent decades substantially altered the fate of these mountain landscapes. Road expansion, often in the name of development, plays a key role.

Many mountain areas in Nepal are physically and economically marginalized and efforts to improve access are common. Poverty, food insecurity, and social inequity are severe, and many rural laborers opt to migrate for better economic opportunities. This motivates road network expansion. Since the turn of the century, Nepalese road networks has almost quadrupled to the current level of ~50 km per 100 km2, among which rural roads (fair-weather roads) increased more than blacktop and gravel roads.

Figure 2: Mountains carved just above Jay Prithvi Highway in Bajhang district of Sudurpaschim province to build a road

Nepalese mountain roads are treacherous and subject to accidents and landslides. Rural roads, which are often called “dozer roads”, are constructed by bulldozer owners in collaboration with politicians at the request of communities (also as part of the election manifesto in which politicians promised road access in exchange for votes and support to win), often without proper technical guidance, surveying, drainage, or structural protection measures. In addition, mountains are sometimes damaged by heavy earthmovers (so-called “bulldozer terrorism”) that cut out roads that lead from nowhere to nowhere, or where no roads are needed, at the expense of economic and environmental degradation. Such rapid and ineffective road expansion happens throughout the country, particularly in the middle hills where roads are known to be the major manmade driver of landslides.

To tackle these complexities, we need to rethink how we approach development in light of climate change. This has to be done with sufficient investigation into our past actions. The Nepalese Community forestry management program, which emerged as one of the big success stories in the world, encompasses well defined policies, institutions, and practices. The program is hailed as a sustainable development success with almost one-third of the country’s forests (1.6 million hectares) currently managed by community forest user groups representing over a third of the country’s households. Another successful example is the innovation of ropeways and its introduction in the Bhattedanda region South of Kathmandu. The ropeways were instrumental in transforming farmers’ lives and livelihoods by connecting them with markets. Locals quickly mastered the operation and management of the ropeway technology, which was a lifesaver following the 2002 rainfall that washed away the road that had made the ropeway redundant until then.

These two examples show that it is possible to generate ecological livelihoods for several households in Nepal without adversely affecting land use and land cover, which in turn contributes to increased landslide risk in the country, as mentioned above.

A rugged landscape is the greatest hindrance to the remote communities in a mountainous country like Nepal. It cannot be denied that the country needs roads that serve as the main arteries for development, while local innovations like ropeways can well complement the roads with great benefits, by linking remote mountain villages to the markets to foster economic activities and reduce poverty. Such a hybrid transportation model is more sustainable economically as well as environmentally.

It is a pity that despite strong evidence of the cost-effectiveness of alternative local solutions, Nepal’s development is still mainly driven by “dozer constructed roads”. Mountain lives and livelihoods will remain at risk of landslides until development tools become more diverse and compatible.

References:

- Gyawali, D. (Ed.), Thompson, M. (Ed.), Verweij, M. (Ed.). (2017). Aid, Technology and Development. London: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315621630

- Gyawali, Dipak; Dixit, Ajaya; Upadhya, Madhukar (2004). Ropeways in Nepal.

- Petley, D. N. (2020). The deadly start to the monsoon season in Nepal – The Landslide Blog – AGU Blogosphere. The Landslide Blog. https://blogs.agu.org/landslideblog/2020/07/24/nepal-2020/

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

The International Year of Basic Sciences for Sustainable Development (IYBSSD) will focus on these links between basic sciences and the Sustainable Development Goals. It is proposed to be organized in 2022 by a consortium of international scientific unions and scientific organizations* led by the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IIUPAP) with the recommendation of a resolution voted by the UNESCO General Conference during its 40th session in 2019. Over 50 national and international science academies and learned societies and around 30 Nobel Prize laureates and Fields Medalists also support this initiative. The Dominican Republic has agreed to propose a resolution for the promulgation of the IYBSSD during the 76th session of the United Nations General Assembly, beginning in September 2021.

The International Year of Basic Sciences for Sustainable Development (IYBSSD) will focus on these links between basic sciences and the Sustainable Development Goals. It is proposed to be organized in 2022 by a consortium of international scientific unions and scientific organizations* led by the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IIUPAP) with the recommendation of a resolution voted by the UNESCO General Conference during its 40th session in 2019. Over 50 national and international science academies and learned societies and around 30 Nobel Prize laureates and Fields Medalists also support this initiative. The Dominican Republic has agreed to propose a resolution for the promulgation of the IYBSSD during the 76th session of the United Nations General Assembly, beginning in September 2021.

You must be logged in to post a comment.