Jul 26, 2019 | Environment, Systems Analysis, Young Scientists

By Luiza Toledo, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2019

2019 YSSP participant Roope Kaaronen investigates how changes in the urban environment affect people’s behavior and whether they will find it easy to engage in sustainable behavior in different environments.

Technological and industrial advances in many sectors have made our lives easier, but they have also contributed to a less sustainable way of life. From the industrial revolution to the present day, CO2 emissions have increased by 40% and about 95% of this increase can be attributed to human actions. We can therefore say that our actions shape the environment we live in. But how does the environment we live in in turn shape our attitudes and behavior?

Apart from the vast amount of information available to us and an increasing awareness of more sustainable consumption, our society still has a growing carbon footprint, which means that attitudes around sustainability are not really translating into behavior. There is a gap between having environmental knowledge and environmental awareness, and displaying pro-environmental behavior. Apparently, the answer to translating attitudes into behavior could have more to do with design than awareness.

Roope Kaaronen, YSSP participant. © Kaaronen

Roope Kaaronen, a member of this year’s IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) cohort, has made it his goal to study behavior change and the adoption of sustainable habits. His project investigates how changes in the urban environment will affect people’s behavior and whether people will find it easy to engage in sustainable behavior in different environments. He is looking at how pro-environmental behavior patterns emerge from processes of social learning (such as teaching and imitation), habituation, and niche construction (a process where agents shape the environment they act in).

“I am particularly interested in how the physical environment shapes our behaviors, because people often assume that they have a pro-environmental attitude or values, and that this automatically translates into sustainable behavior. Research however shows that this is often not the case. So actually, the physical environment is more important in determining how we behave than we think,” he explains.

For instance, suppose that you would like to start recycling more but your city doesn’t have a proper selective waste collection system. Because the infrastructure needed to promote pro-environmental behavior is missing, this can lead to feelings of frustration and hopelessness, which could in turn cause people to give up on even trying to engage in the behaviors that could lead to more sustainable outcomes.

Kaaronen uses agent-based modeling in his research to model the cultural evolution of sustainable behavior patterns. The idea is to study how opportunities for action can have self-reinforcing effects on behavior. He included agents who move on a “landscape of affordances” in his model, and these agents are connected to each other in a social network. In this context, the term “agents” represents individuals or groups in society.

Social psychology describes pro-environmental behavior as conscious actions made by an individual to minimize the negative impact of human activities on the environment. For Kaaronen, this means that we can only achieve sustainable goals if we change our behaviors or habits very quickly.

“I think that it’s not realistic to expect that technology will solve all our problems. We will have to start behaving differently,” he says.

Unfortunately, people very often assume that individuals’ actions don’t have as much impact as collective actions, leading them to postpone their own pro-environmental behaviors. There have been a lot of discussion in the media around whether one person’s attitude could have an impact on the environment, in other words, should the focus be on each individual making changes in the way they live, or should the focus be on whole systems changing. To Kaaronen, these two approaches are connected.

“Systems emerge from individuals and their collective interactions. As we are social animals, our actions are inevitably copied and imitated by other people. This means that a person who has a lot of influence will have many people copying them. In other words, whenever we talk about private environmental behavior, such as recycling or using public transport rather than driving a car, we tend to think that this is just our personal behavior, but of course, our choices form part of a much bigger system,” says Kaaronen.

Woman helps clean the beach of garbage. © Freemanhan2011 | Dreamstime.com

We should be aware that we need politicians to make our pro-environmental choices as easy as possible. As individuals, we have responsibilities because we are part of the social system, but it is up to the political system to encourage this kind of behavior on a larger scale.

In 2007, the Danish government developed a strategy that prioritized bicycling as method of transport in Copenhagen. Since then, the city has seen a rapid increase in the number of people cycling, showing that affordance is important to promoting behavior change. Kaaronen’s model is able to reproduce patterns of behavior change, such as the case of Copenhagen.

“I think in terms of policy, what I am doing is quite applicable in urban design. What I am trying to show is that if we make sustainable behavior easy and lucrative, this can lead to long lasting and self-reinforcing effects on the emergence of sustainable cultures,” he comments.

The advent of social media has made it easy to influence people’s attitudes and behavior. The model that Kaaronen is using also illustrates how behavior change can spread through tightly knit social networks, and how social learning in networks can have self-reinforcing effects on behavior change. He says that we should use this tool to spread awareness about sustainable habits and initiate cultural evolution towards sustainable societies. In terms of behavior, living by example is very important, since it is necessary to show that living a sustainable life is both possible and enjoyable. Kaaronen himself lives this philosophy as he doesn’t drive and tries not to eat meat. He also stopped flying two years ago.

“I am just travelling on the ground right now. It is part of a campaign in the academic environment called #FlyingLess. Buses and trains can take you to interesting places, but it of course takes up a lot of time and I realize that not everyone can do this because they live in places that aren’t well connected.”

We are so used to unsustainable forms of behavior like constantly driving, flying, and consuming meat, but the world needs to realize that this way of living cannot last forever. It is unsustainable. Even though it may appear challenging to change our behavior, Kaaronen’s research offers hope to keep believing that it is possible to change our unsustainable behavior and achieve a sustainable society and environment.

“I think it is important to show that these things are actually possible. We can reach a tipping point towards sustainable systems if enough people just start practicing what they preach,” he concludes.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jun 12, 2019 | Economics, Energy & Climate, Eurasia, Young Scientists

By Dmitry Erokhin, Research Assistant in the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program

Dmitry Erokhin shares his thoughts on the promotion of economic progress and security through energy cooperation, good governance, and connectivity in the digital era.

Nadejda Komendantova and Dmitry Erokhin at the OSCE EEF meeting in Bratislava © Dmitry Erokhin

From 27 to 28 May 2019, Bratislava hosted the Second Preparatory Meeting of the 27th Economic and Environmental Forum of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE EEF) on “Promoting economic progress and security in the OSCE area through energy cooperation, new technologies, good governance and connectivity in the digital era”.

As part of my work on digitalization in Greater Eurasia, I was particularly interested in attending this meeting.

A major part of the event was devoted to questions surrounding energy security, which is a very important factor of cooperation in the OSCE area. All 57 participating states across North America, Europe, and Asia are interested in stable energy supply. Doing energy right is a way to promote progress, security, and prosperity. Orientation towards sustainable development, limiting the use of conventional energy sources, oil conflicts, and cyber attacks make both energy demanders and suppliers search for new solutions. In this regard, the use of renewable resources promises long-term benefits in terms of energy efficiency, new jobs, as well as a secure and resilient energy sector. This is however not possible without peace, which makes the protection of infrastructure crucial. There is no prosperity without peace and no peace without prosperity.

I found it particularly valuable that new technologies were included in the discussion. Blockchain – a system in which a record of transactions made in bitcoin or another cryptocurrency are held across several computers that are linked in a peer-to-peer network – along with big data, are creating new opportunities in the energy sector, for example, in terms of new forms of energy trading. However, they can also pose some risks as they create certain dependencies, thus raising questions of sustainability. For instance, automated driving raises many regulatory issues on how to ensure against cyber attacks and missiles, or how to divide responsibilities between producers and users. Advanced technologies have to be employed safely and efficiently. International organizations could play a vital role in enacting common standards and regulatory norms for digitalization and connectivity in this regard. One grand example here is the single window recommendation, which is a trade facilitation idea that enables international traders to submit regulatory documents at a single location. The idea is that such a system would facilitate trade through good governance.

The establishment of regional communication platforms and the development of science, research, and innovations are of particular importance. Key agents need to talk about secure and clean energy. This could be achieved through intra-institutional cooperation and inclusive dialogue. I believe that institutions like IIASA can play a huge role here.

Talking about new technologies, it is an important task to conduct studies on barriers to trade, especially in the context of blockchain and machine learning technologies in digital trade in order to detect inefficiencies at borders and improve market access. In the energy field, there are many controversial estimates (simultaneously in favor of conventional and renewable energy sources), which also make independent reputable studies essential.

Nadejda Komendantova, a researcher with the Advanced Systems Analysis Program at IIASA also represented the institute at the OSCE meeting, where she moderated a session on protecting energy networks from natural and man-made disasters. The sessions’ participants discussed the impact of these factors on energy security, analyzed opportunities and threats for secure energy networks connected with new technologies, raised questions of resilience, and talked about the mitigation of threats through effective policies and cooperation. The OSCE Critical Energy Infrastructure Protection (CEIP) Digital Training Platform was presented during the session.

To conclude, I would like to emphasize that we need more such constructive and fruitful discussions to catalyze trust, growth, security and connectivity. Partnerships create political will and make open dialogue and mutual support very important. I believe that organizations like IIASA are key to making this possible.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 24, 2019 | Data and Methods, Systems Analysis, Women in Science

By Sibel Eker, IIASA postdoctoral research scholar

Ceci n’est pas une pipe – This is not a pipe © Jaka Vukotič | Dreamstime.com

Quantitative models are an important part of environmental and economic research and policymaking. For instance, IIASA models such as GLOBIOM and GAINS have long assisted the European Commission in impact assessment and policy analysis2; and the energy policies in the US have long been guided by a national energy systems model (NEMS)3.

Despite such successful modelling applications, model criticisms often make the headlines. Either in scientific literature or in popular media, some critiques highlight that models are used as if they are precise predictors and that they don’t deal with uncertainties adequately4,5,6, whereas others accuse models of not accurately replicating reality7. Still more criticize models for extrapolating historical data as if it is a good estimate of the future8, and for their limited scopes that omit relevant and important processes9,10.

Validation is the modeling step employed to deal with such criticism and to ensure that a model is credible. However, validation means different things in different modelling fields, to different practitioners and to different decision makers. Some consider validity as an accurate representation of reality, based either on the processes included in the model scope or on the match between the model output and empirical data. According to others, an accurate representation is impossible; therefore, a model’s validity depends on how useful it is to understand the complexity and to test different assumptions.

Given this variety of views, we conducted a text-mining analysis on a large body of academic literature to understand the prevalent views and approaches in the model validation practice. We then complemented this analysis with an online survey among modeling practitioners. The purpose of the survey was to investigate the practitioners’ perspectives, and how it depends on background factors.

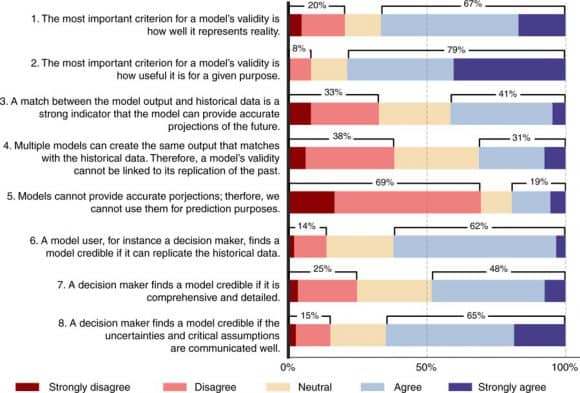

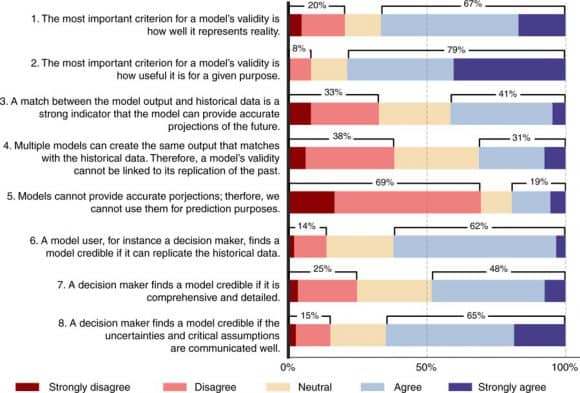

According to our results, published recently in Eker et al. (2018)1, data and prediction are the most prevalent themes in the model validation literature in all main areas of sustainability science such as energy, hydrology and ecosystems. As Figure 1 below shows, the largest fraction of practitioners (41%) think that a match between the past data and model output is a strong indicator of a model’s predictive power (Question 3). Around one third of the respondents disagree that a model is valid if it replicates the past since multiple models can achieve this, while another one third agree (Question 4). A large majority (69%) disagrees with Question 5, that models cannot provide accurate projects, implying that they support using models for prediction purposes. Overall, there is no strong consensus among the practitioners about the role of historical data in model validation. Still, objections to relying on data-oriented validation have not been widely reflected in practice.

Figure 1: Survey responses to the key issues in model validation. Source: Eker et al. (2018)

According to most practitioners who participated in the survey, decision-makers find a model credible if it replicates the historical data (Question 6), and if the assumptions and uncertainties are communicated clearly (Question 8). Therefore, practitioners think that decision makers demand that models match historical data. They also acknowledge the calls for a clear communication of uncertainties and assumptions, which is increasingly considered as best-practice in modeling.

One intriguing finding is that the acknowledgement of uncertainties and assumptions depends on experience level. The practitioners with a very low experience level (0-2 years) or with very long experience (more than 10 years) tend to agree more with the importance of clarifying uncertainties and assumptions. Could it be because a longer engagement in modeling and a longer interaction with decision makers help to acknowledge the necessity of communicating uncertainties and assumptions? Would inexperienced modelers favor uncertainty communication due to their fresh training on the best-practice and their understanding of the methods to deal with uncertainty? Would the employment conditions of modelers play a role in this finding?

As a modeler by myself, I am surprised by the variety of views on validation and their differences from my prior view. With such findings and questions raised, I think this paper can provide model developers and users with reflections on and insights into their practice. It can also facilitate communication in the interface between modelling and decision-making, so that the two parties can elaborate on what makes their models valid and how it can contribute to decision-making.

Model validation is a heated topic that would inevitably stay discordant. Still, one consensus to reach is that a model is a representation of reality, not the reality itself, just like the disclaimer of René Magritte that his perfectly curved and brightly polished pipe is not a pipe.

References

- Eker S, Rovenskaya E, Obersteiner M, Langan S. Practice and perspectives in the validation of resource management models. Nature Communications 2018, 9(1): 5359. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-07811-9 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/15646/]

- EC. Modelling tools for EU analysis. 2019 [cited 16-01-2019]Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/analysis/models_en

- EIA. ANNUAL ENERGY OUTLOOK 2018: US Energy Information Administration; 2018. https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/info_nems_archive.php

- The Economist. In Plato’s cave. The Economist 2009 [cited]Available from: http://www.economist.com/node/12957753#print

- The Economist. Number-crunchers crunched: The uses and abuses of mathematical models. The Economist. 2010. http://www.economist.com/node/15474075

- Stirling A. Keep it complex. Nature 2010, 468(7327): 1029-1031. https://doi.org/10.1038/4681029a

- Nuccitelli D. Climate scientists just debunked deniers’ favorite argument. The Guardian. 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2017/jun/28/climate-scientists-just-debunked-deniers-favorite-argument

- Anscombe N. Models guiding climate policy are ‘dangerously optimistic’. The Guardian 2011 [cited]Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/feb/24/models-climate-policy-optimistic

- Jogalekar A. Climate change models fail to accurately simulate droughts. Scientific American 2013 [cited]Available from: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/the-curious-wavefunction/climate-change-models-fail-to-accurately-simulate-droughts/

- Kruger T, Geden O, Rayner S. Abandon hype in climate models. The Guardian. 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2016/apr/26/abandon-hype-in-climate-models

Oct 16, 2018 | Alumni, Climate Change, Environment, Science and Policy, Women in Science, Young Scientists

Laura Mononen experiencing a creative ”world flow” in the art installation ‘Passage’ by Matej Kren in Bratislava | © Kati Niiles

By Sandra Ortellado, IIASA 2018 Science Communication Fellow

If fashion is the science of appearances, what can beauty and aesthetics tell us about the way we perceive the world, and how it influences us in turn?

From cognitive science research, we know that aesthetics not only influence superficial appearances, but also the deeper ways we think and experience. So, too, do all kinds of creative thinking create change in the same way: as our perceptions of the world around us changes, the world we create changes with them.

From the merchandizing shelves of H&M and Vero Moda to doctoral research at the Faculty of Information Technology at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland, 2018 YSSP participant Laura Mononen has seen product delivery from all angles. Whether dealing with commercialized goods or intellectual knowledge, Mononen knows that creativity is all about a change in thinking, and changing thinking is all about product delivery.

“During my career in the fashion and clothing industry, I saw the different levels of production when we sent designs to factories, received clothing back, and then persuaded customers to buy them. It was all happening very effectively,” says Mononen.

But Mononen saw potential for product delivery beyond selling people things they don’t need. She wanted to transfer the efficiency of the fashion world in creating changes in thinking to the efforts to build a sustainable world.

“Entrepreneurs make change with products and companies, fashion change trends and sell them. I’m really interested in applying this kind of change to science policy and communication,” says Mononen. “We treat these fields as though they are completely different, but the thing that is common is humans and their thinking and behaving.”

Often, change must happen in our thinking first before we can act. That’s why Mononen is getting her doctorate in cognitive science. Her YSSP project involved heavy analysis of systems theories of creativity to find patterns in the way we think about creativity, which has been constantly changing over time.

In the past, creativity was seen as an ability that was characteristic of only certain very gifted individuals. The research focused on traits and psychological factors. Today, the thinking on creativity has shifted towards a more holistic view, incorporating interactions and relationships between larger systems. Instead of being viewed as a lightning bolt of inspiration, creativity is now seen as more of a gradual process.

New understandings of creativity also call on us to embrace paradoxes and chaos, see ourselves as part of nature rather than separate from it, experience the world through aesthetics, pay careful attention to our perception and how we communicate it, and transmit culture to the next generation.

Perhaps most importantly, Mononen found in her research that the understanding of creativity has changed to be seen as part of a process of self-creation as well as co-creation.

“The way we see creativity also influences ourselves. For example if I ask someone if they are creative, it’s the way they see themselves that influences how creative they are,” says Mononen. “I have found that it’s more crucial to us than I thought, creativity is everywhere and it’s everyday and we are sharing our creativity with others who are using that to do something themselves and so on.”

This means on the one hand that we use our creativity to decide who we are and how we see the world around us for ourselves. But it also means that the outcomes and benefits of creativity are now intended for society as a whole rather than purely for individuals, as it was in the past. It may sound like another paradox, but being able to embrace ambiguity and complexity and take charge of our role in a larger system is important for creating a sustainable future.

“From the IIASA perspective this finding brings hope because the more people see themselves as part of systems of creating things, the more we can encourage sustainable thinking, since nature is a part of the resources we use to create,” says Mononen.

Mononen says a systems understanding of creativity is especially important for people in leadership positions. If a large institution needs new and innovative solutions and technology, but doesn’t have the thinking that values and promotes creativity, then the cooperative, open-minded process of building is stifled.

Working in both the fashion industry and academic research, Mononen has encountered narrow-minded attitudes towards art and science firsthand.

“Communicating your research is very difficult coming from my background, because you don’t know how the other person is interpreting what you say,” says Mononen. “People have different ideas of what fashion and aesthetics are, how important they are and what they do. Additionally, scientific concepts are used differently in different fields.”

“We are often thinking that once we get information out there, then people will understand, but there are much more complex things going on to make change and create influence in settings that combine several different fields.” says Mononen.

For Mononen, the biggest lesson is that creativity can enhance the efforts of science towards a sustainable world simply by encouraging us to be aware of our own thinking, how it differs from that of others, and how it affects all of us.

“When you become more aware of your ways of thinking, you become more effective at communicating,” says Mononen. “It’s not always that way and it’s very challenging, but that’s what the research on creativity from a systems perspective is saying.”

Oct 5, 2018 | Climate, Climate Change, Ecosystems, Environment, Food, Food & Water, History, Young Scientists

© Marcus Thomson

By Marcus Thomson, researcher, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

While living in Cairo in 2010, I witnessed first-hand the human toll of political and environmental disasters that washed over Africa at the end of the last century. Unprecedented numbers of migrants were pressing into North Africa, many pushed out of their homelands by conflict and state-failure, pulled towards safer, richer, less fragile places like Europe. Throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, climate change was driving up competition for scarce land and water, and raising pressure on farmers to maintain the quantity and quality of their crops.

It is a similar story throughout the developing world, where many farmers do without the use of expensive chemical fertilizer and pesticides, complex irrigation, or boutique seed varieties. They rely instead on traditional land management practices that developed over long periods with consistent, predictable conditions. It is difficult to predict how dryland farmers will respond to climate change; so it is challenging to plan for various social, economic, and political problems expected to develop under, or be exacerbated by, climate change. Will it spur innovation or, as has been argued for the Syrian civil war[1], set up conflict? A major stumbling block is that the dynamics of human social behavior are so difficult to model.

Instead of attempting to predict farmers’ responses to climate change by modelling human behavior, we can look to the responses to environmental changes of farmers from the past as analogues for many subsistence farmers of the future. Methods to fill in historical gaps, and reconstruct the prehistoric record, are valuable because they expand the set of observed cases of societal-scale responses to environmental change. For instance, some 2000 years ago, an expansive maize-growing cultural complex, the Ancestral Puebloans (APs), was well established in the arid American Southwest. By AD 1000, members of this AP complex produced unique and innovative material culture including the famed “Great Houses”, the largest built structures in the United States until the 19th century. However, between AD 1150 and 1350, there was a profound demographic transformation throughout the Southwest linked to climate change. We now know that many APs migrated elsewhere. As a PhD student at the University of California, Los Angeles, I wondered whether a shift to cooler, more variable conditions of the “Little Ice Age” (LIA, roughly AD 1300 to 1850) was linked to the production of their staple crop, maize.

I came to IIASA as a YSSP in 2016 to collaborate with crop modelers on this question, and our work has just been published in the journal Quaternary International.[2] I brought with me high-resolution data from a state-of-the-art climate model to drive the crop simulations, and AP site information collected by archaeologists. Because AP maize was quite different from modern corn, I worked with IIASA soil scientist Juraj Balkovič to modify the crop simulator with parameters derived from heirloom varieties still grown by indigenous peoples in the Southwest. I and IIASA economic geographer Tamás Krisztin developed a statistical technique to analyze the dynamical relationship between AP site occupation and simulated yield outcomes.

We found that for the most climate-stressed high-elevation sites, abandonments were most associated with increased year-to-year yield variability; and for the least stressed low-elevation and well-watered sites, abandonment was more likely due to endogenous stressors, such as soil degradation and population pressure. Crucially, we found that across all regions, populations peaked during periods of the most stable year-to-year crop yields, even though these were also relatively warm and dry periods. In short, we found that AP maize farmers adapted well to gradually rising temperatures and drought, during the MCA, but failed to adapt to increased climate variability after ~AD 1150, during the LIA. Because increased variability is one of the near certainties for dryland farming zones under global warming, the AP experience offers a cautionary example of the limits of low-technology adaptation to climate change, a business-as-usual direction for many sub-Saharan dryland farmers.

This is a lesson from the past that policymakers might take note of.

[1] Kelley, C. P., Mohtadi, S., Cane, M. A., Seager, R., & Kushnir, Y. (2015). Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201421533.

[2] Thomson, M. J., Balkovič, J., Krisztin, T., MacDonald, G. M. (2018). Simulated crop yield for Zea mays for Fremont Ancestral Puebloan sites in Utah between 850-1499 CE based on temperature dailies from a statistically downscaled climate model. Quaternary International. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2018.09.031

You must be logged in to post a comment.