Nov 10, 2016 | Risk and resilience

By Wei Liu, IIASA Risk and Resilience and Ecosystems Services and Management programs

Disasters caused by extreme weather events are on the rise. Floods in particular are increasing in frequency and severity, with reoccurring events trapping people in a vicious cycle of poverty. Information is key for communities to prepare for and respond to floods – to inform risk reduction strategies, improve land use planning, and prepare for when disaster strikes.

But, across much of the developing world, data is sparse at best for understanding the dynamics of flood risk. When and if disaster strikes, massive efforts are required in the response phase to develop or update information. After that, communities have an even greater need for data to help with recovery and reconstruction and further enhance communities’ resilience to future floods. This is particularly important for the Global South, such as the Karnali Basin in Nepal, where little information is available regarding community’s exposure and vulnerability to floods.

Karnali Basin in Nepal © Wei Liu | IIASA

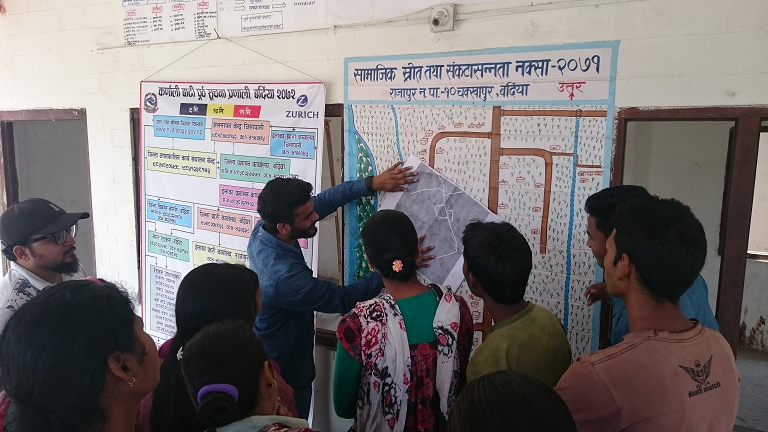

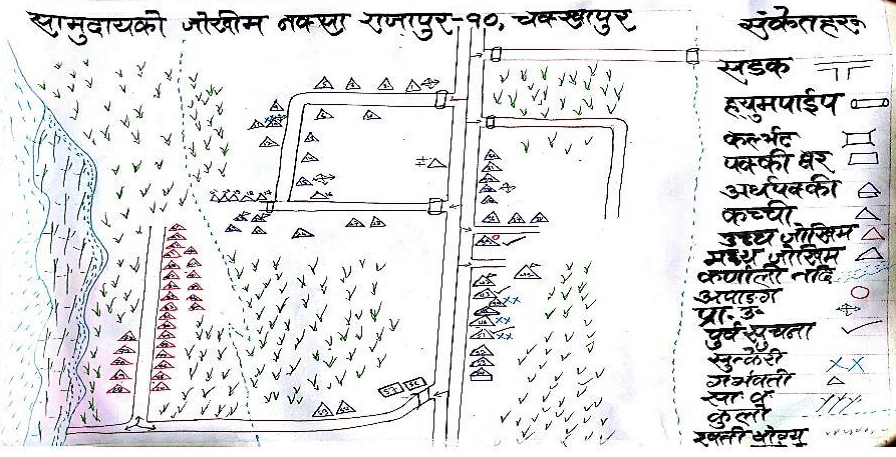

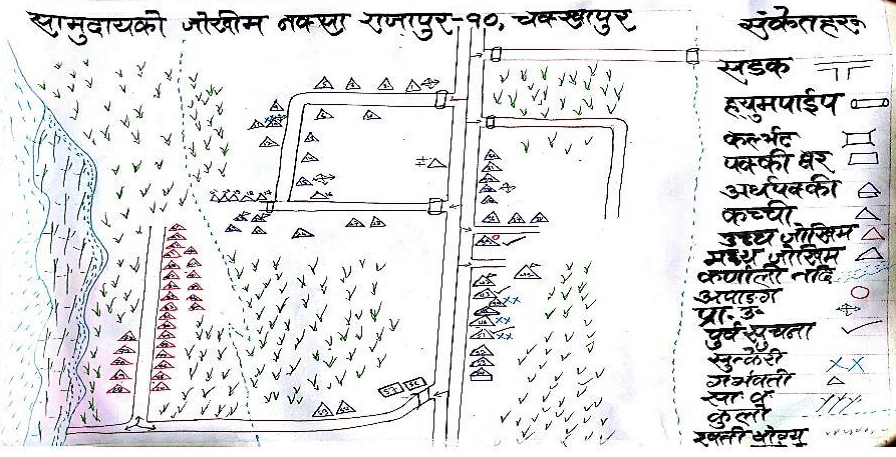

That’s why we are working with Practical Action in the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance to try to remedy this situation. Participatory Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment is a widely used tool to collect community level disaster risk and resilience information and to inform disaster risk reduction strategies. One of our first projects was to digitize a set of existing maps on disaster risk and community resources where the locations of, for example, rivers, houses, infrastructure and emergency shelters are usually hand-drawn by selected community members. Such maps provide critical information used by local stakeholders in designing and prioritizing among possible flood risk management options.

From hand-drawn to internet mapping

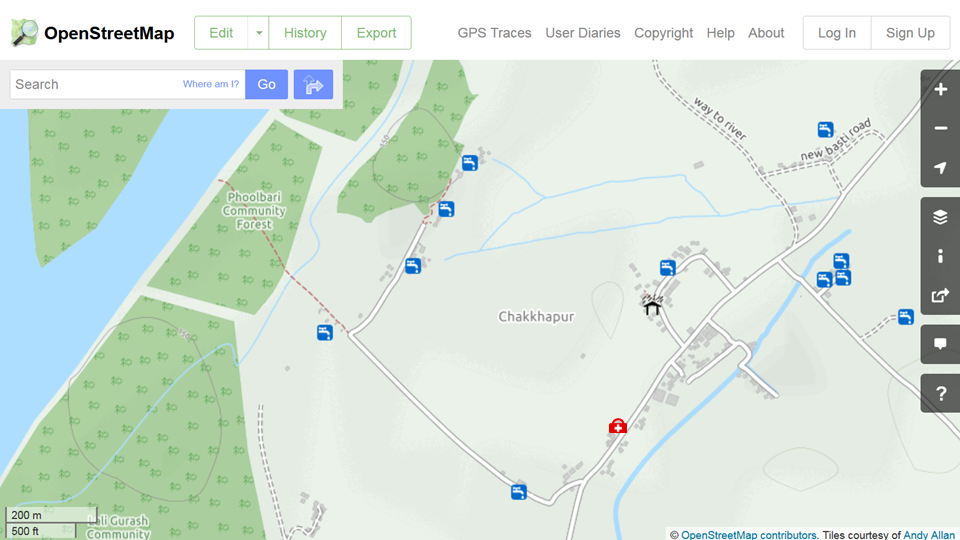

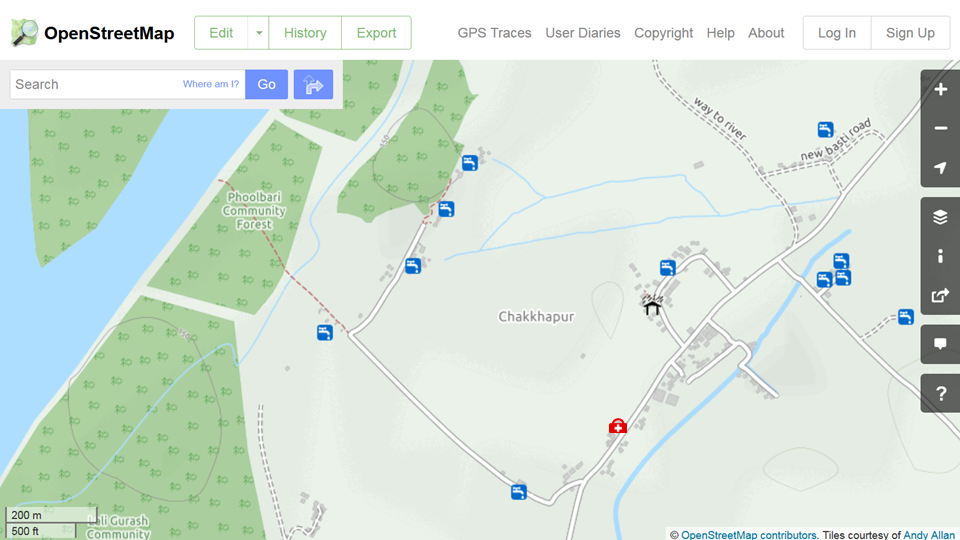

While hand-drawn maps are ideal for working in remote rural communities, they risk being damaged, lost, or simply unused. They are also more difficult to share with other stakeholders such as emergency services or merge with additional mapped information such as flood hazard. With the recent increase in internet mapping, platforms such as OpenStreetMap have made it possible for us to transfer existing maps or capture new information on a common platform in such a way that anyone with an internet connection can add, edit, and share maps. As this information is digital, it makes it easier to perform additional tasks, such as identifying households in areas of high risk or measuring the distance to the nearest emergency shelter, to support effective risk-reduction and resilience-building.

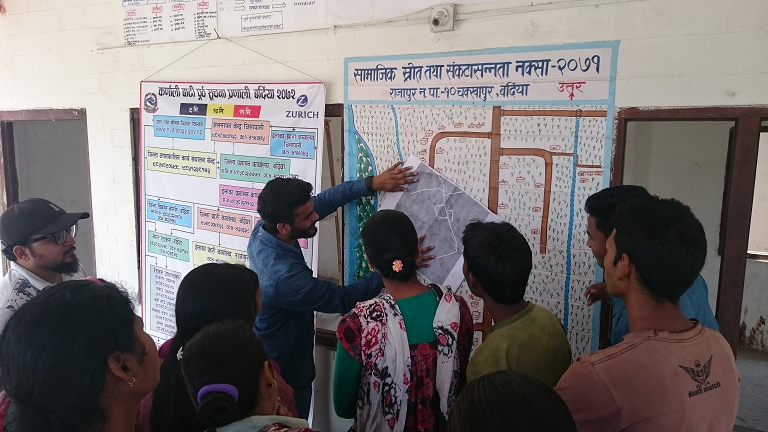

Practical Action Nepal, the Center for Social Development and Research, and community members discuss the transfer of community maps to online maps © Wei Liu | IIASA

From theory to practice

In March 2016, the Project team travelled to two Nepal communities in the Rajapur and Tikapur districts, to pilot the idea of working with a local NGO (the Center for Social Development and Research) and community members, to transfer their maps into a digital environment. The latter can easily be further edited, improved and shared within a broad range of stakeholders and potential users. Local residents in both communities were excited seeing their households and other features for the first time overlaid on a map with satellite imagery. The Center for Social Development and Research was also very enthusiastic about integrating their future community mapping activities with digital mapping, without losing the spirit of participation.

Hand drawn maps produced from community mapping exercises in Chakkhapur, Nepal © Practical Action

The resulting online maps in OpenStreetMap of Chakkhapur, Nepal, showing the location of drinking water, an emergency shelter and medical clinic. ©OpenStreetMap

Increasing resilience through improved information management

The first stage pilot study in the Karnali river basin confirmed the great potential of new digital technologies in providing accurate and locally relevant maps to improve flood risk assessment to support resilience building at the community level. The next step is to further engage local stakeholders. A wider partnership has been established between Practical Action, the Center for Social Development and Research, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis and Kathmandu Living Labs to further build local stakeholders’ capacity in mapping with digital technologies, including a training workshop for NGO staff members in September, 2016. The plan is to have more communities’ flood risk information mapped for designing more effective action plans and strategies for coping with future flood events across the Karnali river basin. A greater potential can be realized when this effort is further scaled up across the region and the results are placed into shared open online databases such as OpenStreetMap.

Further information

- Flood Resilience Portal

- Geo-Wiki Risk

- McCallum, I., Liu, W., See, L., Mechler, R., Keating, A., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., Mochizuki, J., Fritz, S., Dugar, S., Arestegui, M., Szoenyi, M., Laso Bayas, J.C., Burek, P., French, A. and Moorthy, I. (2016) Technologies to Support Community Flood Disaster Risk Reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 7 (2). pp. 198-204. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/13299/

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 3, 2016 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience

By Adriana Keating, research scholar in the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program.

People have been playing games for fun for many thousands of years. But recently some have been designed not to escape from reality, but to improve it. As the world is becoming more and more complex, and the future more and more uncertain, serious games can be used as innovative tools for learning, decision making, improving effective collaboration and developing strategies for success. With games, we can communicate complex realities and learn from our mistakes without costs.

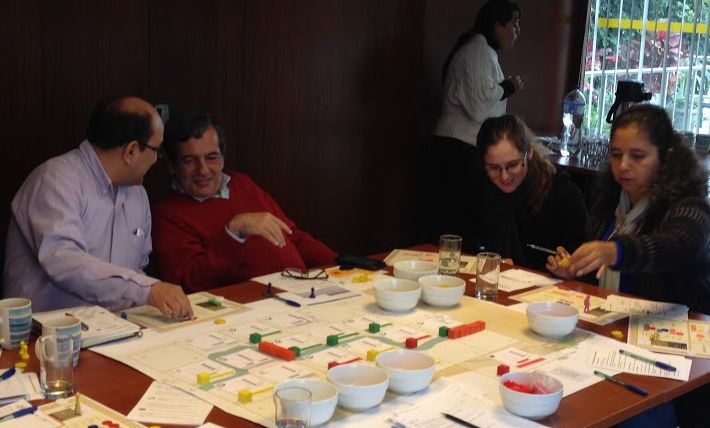

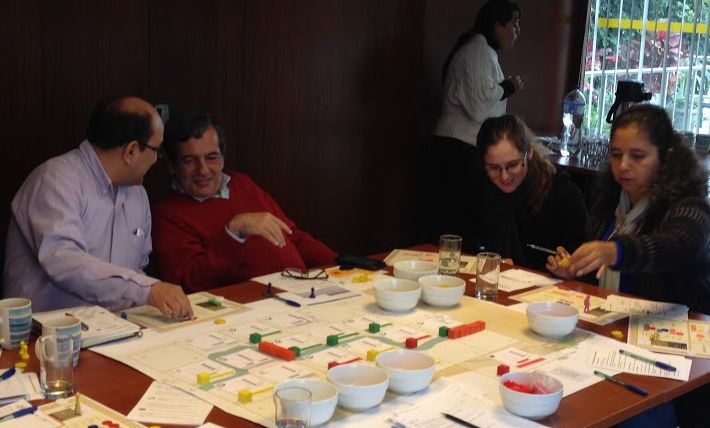

Systems thinking is required to tackle the challenge of managing both flood risk and development: to live in harmony with floods. Games provide the perfect avenue for exploring these challenges. Games that engage participants have been shown to be very successful and powerful dissemination instruments—with broader outreach than traditional reports. In a team made up of myself, Piotr Magnuszewski from the Water Program, Adam French from the Advanced Systems Analysis and Risk and Resilience Programs, and collaborators from the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance, we have been developing a game that can help build flood resilience in developing countries.

The game provoking discussion at a workshop in Jakarta. © Adriana Keating

Because games are experienced as something that feels real, more information is retained, learning is faster, and an intuition is gained about how to make real decisions. Critically, the IIASA Flood Resilience Game is designed to help participants— such as NGO staff working on flood-focused programs—to identify novel policies and strategies which improve flood resilience. In its current form it is a board-game played by at least eight players, who each take on a role as a member of a flood prone community. The direct interactions between players create a rich experience that can be discussed, analysed, and lead to concrete conclusions and actions. This allows players to explore vulnerabilities and capacities—citizens, local authorities and NGOs together—leading to an advanced understanding of interdependencies and the potential for working together.

The game draws on IIASA research on the deep-seated challenges in the typical approach to flood risk management. It allows players to experience, explore, and learn about the flood risk and resilience of communities in river valleys. It lets them experience the effects on resilience of investments in different types of “capital”—such as financial, human, social, physical, and natural. The impacts of flood damage on housing and infrastructure are also an important part of the game, as well as indirect effects on livelihoods, markets, and quality of life.

Players in Peru. © Adam French.

Playing the game can also improve understanding of the influence of preparedness, response, reconstruction on flood resilience. Importantly, it demonstrates the benefits of investment in risk reduction before the flood strikes, such as via land use planning and flood proofing homes. The effects of institutional arrangements, such as communication between citizens and with government, also become clearer during the course of the game.

Finally, participants can explore the complex outcomes on the economy, society and the environment from long-term development pathways. This highlights the types of decisions needed to avoid creating more flood risk in the future, incentivizing action before a flood through enhancing participatory decision-making. All these complex ideas are experienced with simple, concrete game elements that participants can connect with their daily realities.

From a researcher’s perspective, observing game play deepens our understanding of stakeholder motivations in relation to flood resilience. The game also contributes to better understanding and use of IIASA research via the Zurich flood resilience measurement tool, a ground-breaking approach to resilience measurement.

After several field tests in Jakarta and Lima with staff from the NGOs Practical Action, Red Cross Indonesia, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Mercy Corp, Plan and Concern Worldwide, the game is now being refined. The next version will be released soon, and the possibility of a mobile application to allow players to handle more complex dynamics while interacting in the workshop is being explored.

The game was developed in collaboration with the Centre for Systems Solutions, Poland, and with funding from the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 4, 2016 | Risk and resilience

By Junko Mochizuki, Research Scholar, IIASA Risk and Resilience Program

Experts in the field of emergency management like to emphasize that there are important “lessons learned” in the aftermath of disaster situations. After large disaster events such as the 2015 earthquake in Nepal, and 2013 super typhoon Yolanda in Philippines, forensic investigations are often conducted to reveal ”what went wrong” in the chains of command, identifying what we can do differently when the next big one strikes. Such forensic investigations are not only relevant for the field of emergency management, but also for the field of disaster and climate risk management, which seeks to identify the underlying causes of what went wrong in the long chains of developmental policy intervention.

Survivors of Super Typhoon Yolanda in Tacloban City, Philippines, 2013. (cc) UN Photo/Evan Schneider

Over the years, researchers have identified a number of root causes that increase disaster risk—such as weak building codes and land use policy enforcement and overemphasis on ex-post emergency response as opposed to proactive management of disaster risk. Also, decades of economic studies looking at the costs and benefits of risk reduction investment show that such investment often pays off in the longer run. Yet, as the recent global trends of rising disaster risk unfortunately testify—we are far from learning these lessons effectively, or at least fast enough to beat the rising risk posed by future climate change: Global annual average disaster loss is estimated to have risen to approximately $300 billion in 2015 according to the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR).

As the special representative of the secretary general for disaster risk reduction, Robert Glasser wrote in the Guardian last week, “Every time there’s a mega disaster, there are lessons learned… The key question is always, how do you keep up the awareness after a couple of years?”

That is why the IIASA Risk and Resilience program’s research is increasingly focused on cognitive, behavioral, and governance aspects of societal learning on disaster risk reduction. We are currently working with public, private, and civil society stakeholders, asking the questions of why we, as a collective society, continue to fail to act on these lessons learned in disaster risk management and what we can do to change it. By combining both quantitative and qualitative systems analysis approaches, we are untangling why we make decisions the way we do, and what processes and institutional mechanisms directly and indirectly affect disaster risk and developmental outcome over the long term.

Given that catastrophic disasters are by definition rare events (hence opportunities for learning is naturally limited), we are doing this using novel methods such as participatory gaming or policy exercises in which we create virtual opportunities for stakeholders to experience complex decision-making in a safe learning environment. By creating stylized context for common decision-making (such as rural farmers making longer-term decisions on livelihood diversification, or urban planners addressing rising disaster risk due to rapid population growth), these gaming spaces serve as mechanisms through which stakeholders can not only learn about their cognitive and behavioral assumptions, but also through which learning can be accelerated, repeated, and shared among different communities facing similar development and disaster risk reduction challenges. We are running such policy exercises in the context of our flood resilience project and internal gaming project .

Decades of research have shown that there are common global lessons on development and disaster risk reduction but they are not so easily learned in practice. It is too often that that the windows of opportunities for policy learning are limited and we continue with business-as-usual of “lessons unlearned.” Creating an enabling environment for iterative learning is no easy task under these pragmatic constraints, but we hope that a bit of creativity and lots of hard work will eventually pay off in the long run.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 15, 2016 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience

By Thomas Schinko, IIASA Risk, Policy and Vulnerability Program

Climate change is projected to disproportionately affect people in developing countries, through extreme weather events and slow onset events such as rising sea levels. Because the countries most affected by climate change are also those who contributed the least to the problem and with the least capacities to cope, one of the major issues in recent climate negotiations has been how to support those nations’ efforts to adapt and to address climate impacts beyond adaptation.

To address this problem, in 2013 the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) established the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) for Loss and Damage Associated with Climate Change Impacts (WIM).

Yet at the Paris climate talks in December, the future of the WIM was in limbo. The Global South argued for loss and damage to be a key part of an eventual agreement, while the Global North argued for including it under the adaptation agenda. In the end, the Paris agreement quite prominently featured loss and damage. However the Global North’s fears of signing up to a mechanism that makes them liable for unlimited damage claims in the future have been addressed by adding a specific paragraph to the agreement stating, “the agreement does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation.”

A flood in Bangladesh in 2009. Flooding is project to increase with climate change, yet arguments remain about attributing specific events to the influence of climate change. Photo Credit: Amir Jina via Flickr

Building on this reconfirmed support for the mechanism, the second meeting of the Executive Committee of the WIM was held 2–5 February 2016, in Bonn, Germany. The main purpose of the meeting was to give an update on the delivery of specific activities and to consider relevant requests arising from COP21. The Paris agreement requests the establishment of (1) a clearinghouse for risk transfer to facilitate the implementation of comprehensive risk management strategies and (2) a task force to address displacement issues. On the first issue, discussions have focused on the need to move beyond focusing solely on risk transfer and the link between current disaster risk management practice and climate adaptation as there are important overlaps.

As an observer, I could feel the presence of team spirit among the committee members, all honestly committed to help the most vulnerable people. Yet one issue remained hotly debated: the degree to which anthropogenic climate change can be blamed for natural disasters and extreme weather events. I saw a strong divide between committee members from the Global North and South and between those with a strong background in disaster risk management in contrast to those coming from a climate change background. Nevertheless, even in that regard I see a good chance for a joint vision to emerge, if we can distinguish two levels of the loss and damage discourse: the practical implementation on the ground vs. the political dimension.

On the practical implementation side, a pragmatic compromise became palpable: Building on decades of experience in disaster risk management related to weather extremes and the climate variability, it was identified as an entry point to deal with current and future climate risks – whether they are triggered or intensified by climate change or not. The political level, which circles around climate finance and the question of who is going to pay for losses and damages is quite another matter. Here the anthropogenic element is existentially important, as it builds the foundation for international support under the UNFCCC. If reference to anthropogenic climate change is left out of the loss and damage discourse, the UNFCCC might lose its mandate for support, as disaster risk management falls under national responsibility. Once this door closes it could remain shut, though another one might open (e.g. via civil law).

Women in Thata, Pakistan line up for water following 2010 floods. Photo Credit: Asian Development Bank via Flickr

To overcome the political barriers and to build upon the convergence with respect to the short-term practical implementation, we suggest to foster an iterative and comprehensive risk management approach, linking risk prevention, risk reduction, risk retention, risk transfer, as well as ex-post relief and reconstruction to effectively tackle different layers of climate risks.

However, it is important not to lose track of climate change as a risk driver, by consequently screening new scientific and empirical insights. This is crucial, as future risks might substantially increase due to climate change, requiring an iterative adaptation of current practices and support by the international community.

To support such an approach, rigorous scientific input, bringing together researchers from various disciplines, practitioners, NGOs, and policy makers is crucial. Together with international partner institutions, in November 2015 we initiated a scientific hub on loss and damage to provide such input. The envisaged clearinghouse for risk transfer and the task force for climate-related displacement could become key recipients for information generated by our network, packaged with further information and distributed to make it actionable; particularly addressing the needs of the most vulnerable developing countries.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 27, 2016 | Climate Change, Postdoc, Risk and resilience

By Mia Landauer, a Finnish postdoc at IIASA Risk, Policy and Vulnerability Program and Arctic Futures Initiative

When I was a child I did not like cross-country skiing. One reason was that like many other schoolmates in Finland, I had no other option than to ski to school throughout the winter, even when temperatures were below -20 C, and even though my skis were too big because I got them from my sister and so old that they could have broken anytime.

When I decided to write my dissertation in Austria about climate adaptation of winter tourism, I found I still couldn’t get away from skiing. My professor at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU) asked me to join a research team investigating this topic. “What a great tradition you have in Finland! My friend and colleague from METLA (now Natural Resources Institute) in Finland would love to do research with us but with somebody who knows about cross-country skiing! You are the perfect match!” I guess I was too shy to admit that I was not excited about having cross-country skiing as a case study—but I decided to give it a try.

Cross country skiing in Finland is practiced by all age groups (voluntarily or not). Photo Credit: © Mia Landauer

Cross-country skiing is socially and culturally a very important activity in Finland, with considerable health benefits. Forty-two percent of the population practice skiing annually and 98% have the skills. But cross-country skiing, like other snow-based activities, is affected by climate change: even Nordic countries are now seeing lack of snow, shift of seasons, and extreme weather events. The winter 2015/2016 has been no exception. Many Finns are concerned that losing this activity would lead to reduced well-being and loss of cultural tradition. Furthermore, economic impacts on tourism regions brought about by a decrease in skiing would cause problems to local economies heavily dependent on snow-based tourism.

Although vulnerability indicators of some other tourism sectors such as beach tourism exist, nobody had thought about cross-country skiing. So we decided to develop an index, based on climatic observations together with extensive survey data on skiers living in climatically different regions in Finland.

We found that exposure to changes in snow conditions have a considerable effect on regional vulnerability. The most vulnerable skiers are in southernmost parts of Finland, which makes sense. But it is not only the amount of snow and length of winter that matter. We also found that skiers in North and East Finland have the highest capacity to adapt, as indicated by their ability to ski: having the necessary skills and equipment, as well as capacity and willingness to travel to be able to ski.

However, the results also show that if it we could enhance these components of adaptive capacity, also the skiers in the south would have a chance. If there are no adaptation options (no artificial snow tracks, no indoor skiing facilities, or simply no interest to use these, or no money or time to travel to be able to ski), in the short term the Finnish cross-country skiing population will face impacts on health, well-being, and quality of life. In the long term, the skiing culture could be lost. Furthermore, decline in demand would lead to regional economic losses in tourism-dependent local economies.

Attempts are being made to maintain the skiing tradition. Nowadays there are a lot of organized activities where kids are introduced to outdoor activities in a playful and educational environment, and ski school and clubs are being established. They play an important role to create a close and pleasant relationship to nature and increase motivation for skiing. But of course the most important element for skiing is snow.

I have always had a very close relationship to nature. Believe me or not, sometimes I do go skiing although it also brings back the unpleasant memories. Despite them, wintery landscapes and nature experience have motivated me to continue skiing as an adult. The gray and rainy winters make me worried and I simply cannot see myself skiing in a ski tunnel… Albeit “you will never know the true value of a moment until it becomes a memory“, I want snow!

Cross country ski track in Ruka, Finland Photo Credit: © Timo Newton-Syms via Flickr

More information:

Project: “Map Based Assessment of Vulnerability to Climate Change Employing Regional Indicators” (MAVERIC)” http://www.syke.fi/projects/maveric

References

Landauer, M., Sievänen, T., & Neuvonen, M. (2015). Indicators of climate change vulnerability for winter recreation activities: a case of cross-country skiing in Finland, Leisure/Loisir, 39:3-4, 403-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2015.1122283

Landauer, M., Haider, W., & Pröbstl, U. (2014). The influence of culture on climate change adaptation strategies: Preferences of cross-country skiers in Austria and Finland. Journal of Travel Research 53(1), pp. 95-109. doi: 10.1177/0047287513481276

Landauer, M., & Sievänen, T. (2011). Suomalaisten maastohiihtäjien sopeutuminen ilmastonmuutokseen. In T. Sievänen & M. Neuvonen (Eds.), Luonnon virkistyskäyttö 2010 (pp. 91–101). Vantaa: Working Papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute, 212.

Landauer, M., Sievänen, T., & Neuvonen, M. (2009). Adaptation of Finnish cross-country skiers to climate change. Fennia 187 (2), pp. 99–113. http://ojs.tsv.fi/index.php/fennia/article/view/3697

Neuvonen, M., Sievänen, T., Fronzek, S., Lahtinen, I., Veijalainen, N., & Carter, T. R. (2015). Vulnerability of cross-country skiing to climate change in Finland – An interactive mapping tool. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 11, 64–79. doi:10.1016/j.jort.2015.06.010

Neuvonen, M. & Sievänen,T. (2011). Ulkoilutilastot 2010 (Outdoor Recreation Statistics 2010). In: Sievänen, T. & Neuvonen, M. (toim.). Luonnon virkistyskäyttö 2010. Metlan työraportteja / Working Papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute 212: 133–190

Perch-Nielsen, S. L. (2010). The vulnerability of beach tourism to climate change – An index approach. Climatic Change, 100(3–4), 579–606. doi:10.1007/s10584-009-9692-1

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 30, 2015 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience

By Thomas Schinko and Reinhard Mechler, IIASA Risk, Policy and Vulnerability Program

Discussions on dealing with the already palpable as well as future burdens from climate change have moved into the spotlight of international climate policy. They are being tackled as part of the climate negotiations via the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts (Loss and Damage Mechanism), a measure for dealing with impacts and adaptation related to extreme climate events and slow onset events that was agreed in 2013. Debate on the scope, framing and on how the mechanism will eventually be implemented is still continuing, and is heavily framed around moral issues such as compensation, liability, and a need for attributing disasters to climate change, which is a difficult and complex issue.

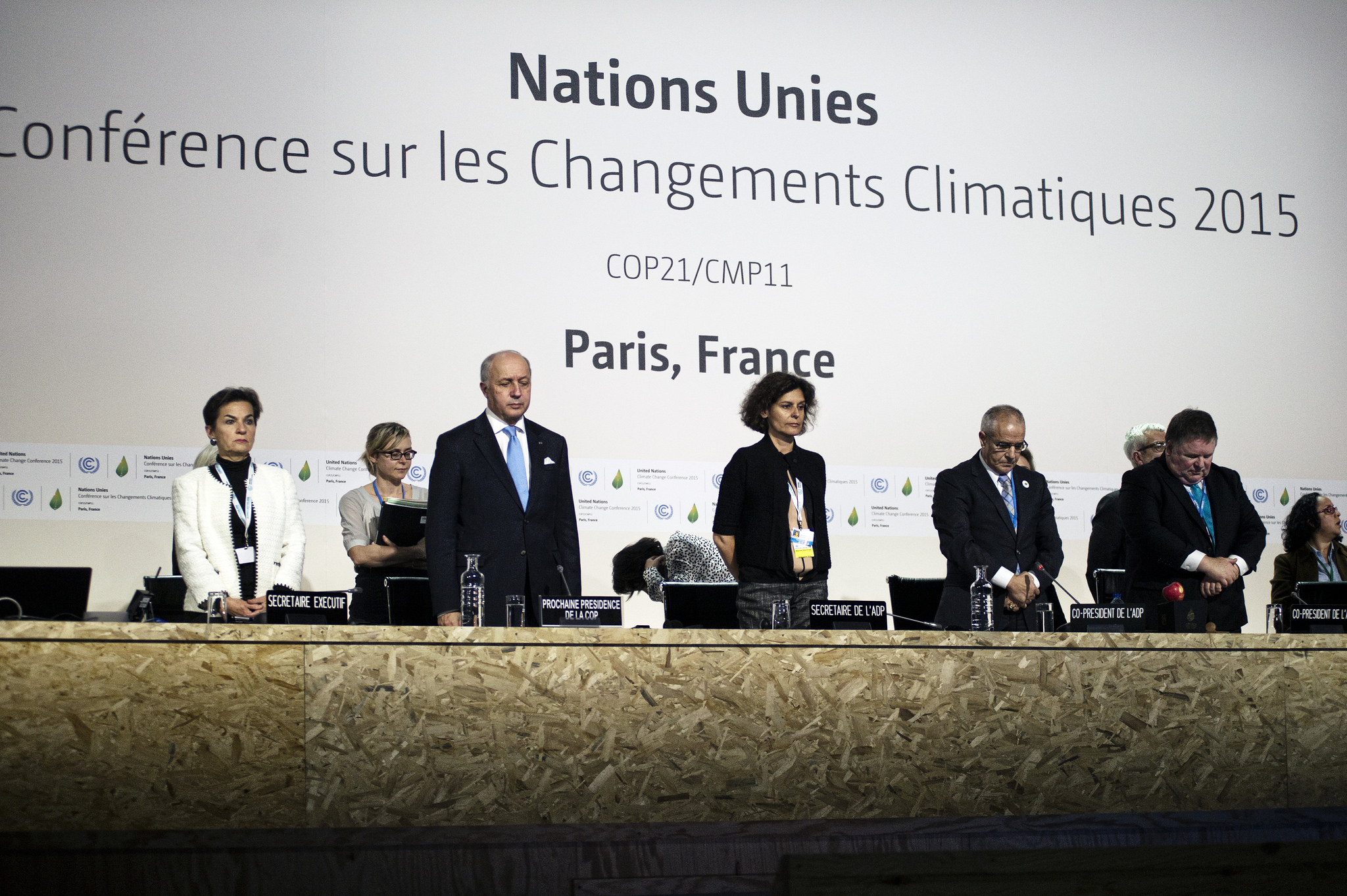

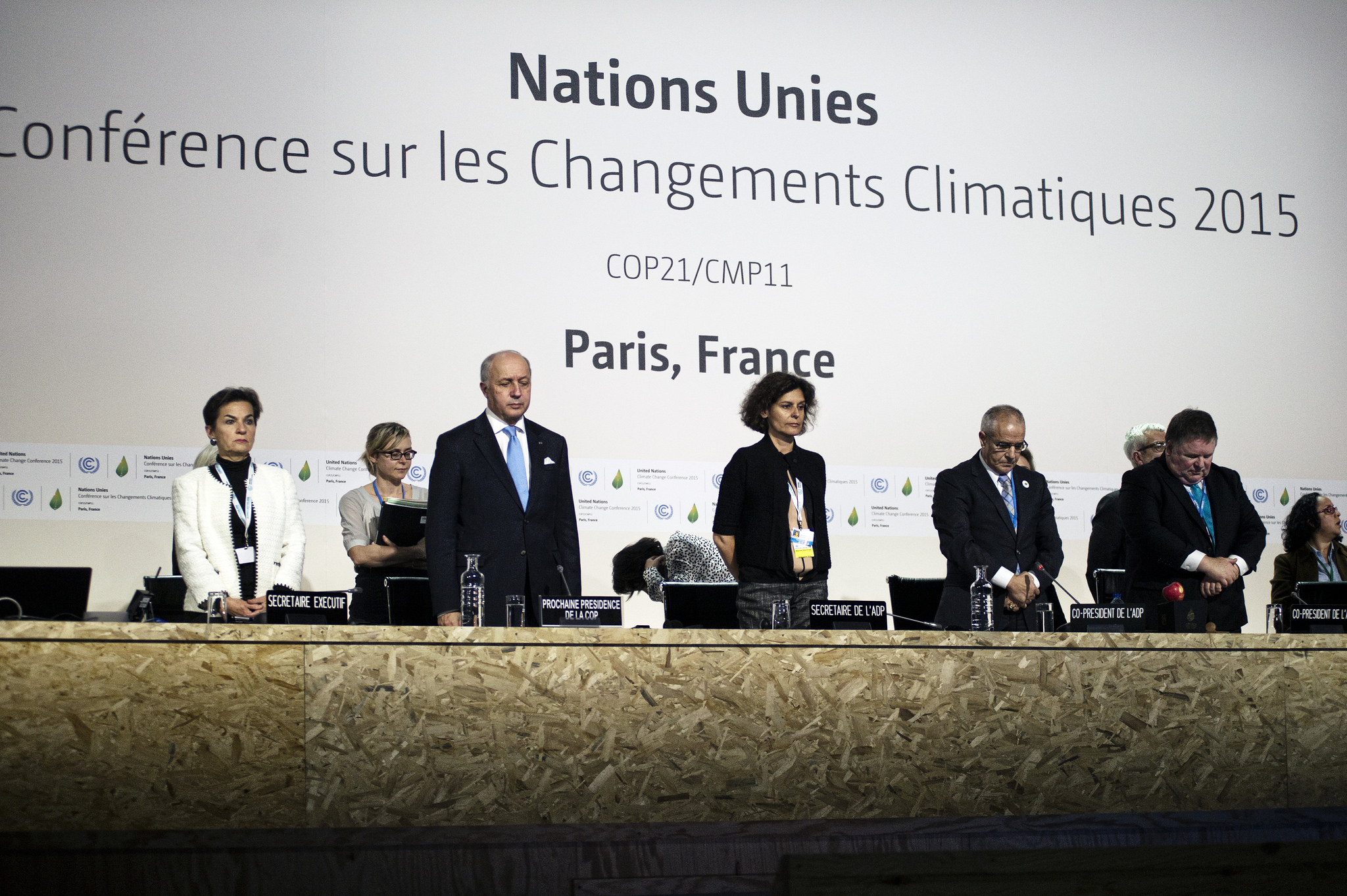

Opening of COP 21 on 29 November 2015. Photo: Benjamin Géminel via Flickr

To help move this contentious debate forward, we recently organized a meeting at IIASA to set up a broad scientific network to support work under the Loss and Damage Mechanism with rigorous and evidence-based research.

Since the first climate negotiations, climate justice has been a major source of contention, with countries disagreeing on the level of responsibility for climate change and the extent to which developed and developing countries should contribute to the solutions. These discussions have predominantly focused on climate mitigation responses, but over the last few years, impact and risk issues have moved into the limelight.

Discussions in the run-up to the 21st Conference of the Parties to the Climate Convention (COP 21) in Paris make it clear that answering key questions revolving around climate justice and climate finance will be pivotal for the conference to deliver on any global climate change agreement.

Even though some rich countries currently appear to acknowledge the central role of a mechanism covering losses and damages within a new global climate agreement to be negotiated at COP 21 in Paris, huge reservations remain. With changing climates, extreme weather events are likely to increase in frequency as well as in intensity. The global North fears exposure to soaring claims for financial compensation by countries of the global South, which will be facing the most severe risks from climate change. In fact, even the meaning and nature of Loss and Damage is still being debated – some suggest the Loss and Damage mechanism should be part of adaptation, while others want it to focus on residual risks that remain after adaptation efforts have been taken. For example, it could finance potential climate-induced migration.

Discussion of compensation raises complex issues about liability, and would presumably require attribution of losses and damages to emitters. Indeed, climate science has been making great progress in attribution research. Recent work has shown a significant human element in mega-events such as superstorm Sandy in 2013 in the US or the Australian heatwave in 2013. Yet, as our kick-off meeting reconfirmed, linking anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions to extreme weather events and to risks for people and property will remain extremely complex, not least as risks from climate-related events are shaped by many factors, including climate variability, rising exposure of people and assets, as well as socio-economic vulnerability dynamics. While the basic case for climate justice has been made, the concrete, enforceable case remains much harder to establish.

A protest for “climate justice” at Quezon City, Philippines on 14 November 2015. Photo: RB Ibañez via Flickr

For these good reasons and to not derail the debate by fixating on questions regarding liability, the debate has extended beyond the narrow focus on compensation – the omnipresent elephant in the room of the UNFCCC process. The meeting at IIASA, which brought together 14 researchers from 10 institutions and 8 countries, also suggested that for a productive discussion, it makes sense to focus broadly on managing various climate risks by fostering current policies and practices while keeping the climate justice debate in close consideration.

This proposal essentially suggests to build on a long history of managing climate-related (and geophysical driven) extremes by employing a broad portfolio of different disaster risk management tools, including financial instruments such as insurance or regional risk pools. As identified also by the IPCC’s 5th assessment report, building on this body of knowledge and practice for comprehensively tackling existing and increasing extremes, holds a lot of promise and has seen international support, e.g. by the Sendai Framework for Action.

The discussion at IIASA focused on these two angles – climate justice and climate risk management – and worked out the following specific foci and building blocks for an evidence-based research approach to support the operationalization of the Loss and Damage Mechanism:

- Articulation of principles and definitions of Loss and Damage, including ethical and normative issues central to the discourse (e.g. liability and responsibility).

- Definition of the Loss and Damage space vis-á-vis the adaptation space.

- Research on the politics and institutional dimensions of the debate.

- Defining the scope for dealing with sudden-onset risk versus slow-onset impacts.

In the coming months the novel network effort will tackle these issues and questions in order to provide actionable but research-based input into the Loss and Damage deliberations.

Note: The authors thank the researchers present at the kick-off event at IIASA for their input on the topic and this blog post: Florent Baarsch (Climate Analytics, Berlin), Laurens Bouwer (Deltares, Delft), Rachel James (University of Oxford), Stefan Kienberger (University of Salzburg), Ana Lopez (University of Oxford), Colin McQuistan (Practical Action, Rugby), Jaroslav Mysiak (FEEM, Venice), Ilan Noy (University of Wellington), Joeri Roegelj (IIASA), Olivia Serdeczny (Climate Analytics, Berlin), Swenja Surminski (LSE, London), Koko Warner (UNU-EHS, Bonn)

References

Bouwer LM (2013). Projections of future extreme weather losses under changes in climate and exposure. RiskAnalysis 33(5):915–930

Herring, S.C., Hoerling, M.P., Peterson, T.C., Stott P.A. (eds) (2014). Explaining extreme events of 2013 from a climate perspective. Special Supplement to the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 95(9)

James, R., Otto, F., Parker, H., Boyd, E., Cornforth, R. Mitchell, D. and M. Allen (2014). Characterizing loss and damage from climate change. Nature Climate Change 4: 938-39

Mechler, R. Bouwer, L., Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., Aerts, J., Surminski, S. (2014). Managing unnatural disaster risk from climate extremes. Nature Climate Change 4: 235-237

Peterson, T.C., Hoerling, M.P., Stott, P.A., Herring, S.C. (2013). Explaining Extreme Events of 2012 from a Climate Perspective. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 94: S1–S74. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-13-00085.1

Trenberth, K.E., Fasullo, J.T., Shepherd, T.G. (2015). Attribution of climate extreme events. Nature Climate Change 5: 725–730. doi:10.1038/nclimate2657

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.