Jul 30, 2015 | Alumni, IIASA Network, Risk and resilience

By Bruce Beck, Imperial College London and Michael Thompson, IIASA Risk, Policy and Vulnerability (RPV) Program.

What do Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium in London, the now glorious heritage of Islington’s housing stock, and the cable-car system in Kathmandu for getting milk supplies to that city, all have in common?

They are (or were) all transformative in their own way. All are commendable outcomes from the process of city governance that we argue will be essential for Coping with Change, the subject of our working paper for the Foresight Future of Cities project. Each is a primary case study in the analysis of our paper. We call this kind of governance ‘clumsiness’. It is something that does not evoke any sense of the familiar attributes of suaveness, elegance, and consensuality implied and valued in most other kinds of governance. So what, then, makes this thing with such an awkward, provocative name so relevant to the future of cities?

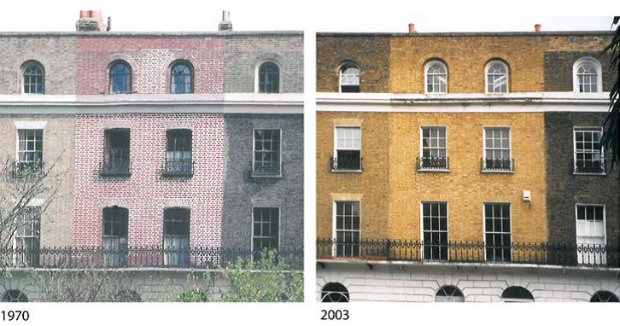

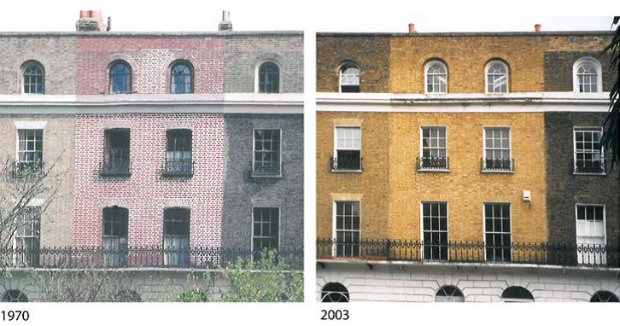

Before and after: Islington’s clumsy and resilient resurgence.

Imagine the city being buffeted about by all manner of social, economic, and natural disturbances over time. There will be times for taking risks with the city’s affairs, and times for avoiding them, or managing them, even just absorbing them – 4 mutually exclusive ways of apprehending how the world works, as it were, and 4 accompanying styles of coping.

In the financial industry, this risk typology has been referred to as the 4 seasons of risk. These are strategically and qualitatively different macroscopic regimes of system behaviour; coping with change between one and another of them is every bit as strategically significant. Conventionally, we recognise only 2 of these regimes: those giving rise to boom and bust in the economy. They reflect just 2 of the 4 ways of understanding the world and acting within it. The nub of the distinctive advantage of clumsiness over other forms of governance for coping with change and transformation is the richness of its (fourfold) diversity of perspective, from which may derive resilience and adaptability in the city’s response to any disturbance – big or small, economic, social, or natural.

Clumsiness is most assuredly deeply participatory. Its process is assiduously supportive of robust, noisy, disputatious debate: witness the gyrations in the Arsenal, Islington, and (especially so) Kathmandu case studies. This is exactly as one should expect of any meaningful engagement among the city’s stakeholders: the public-sector agencies, community activists, private-sector businesses, and so on, all with their own vested interests. The 4 ways of seeing the world are mutually opposed; each is sustained in its opposition to the others, as will be the shaping of their aspirations for the future. Each needs the challenges from the others, not least to avoid the ‘group-think’ in governance that is of such considerable concern to government in managing financial risk.

At the peak of deliberative quality in governance, all 4 outlooks are granted access and responsiveness in the debate, in the process of clumsiness, in other words, in coming to a decision or policy — with ever higher social consent. And in the clumsiest of outcomes, each opposing group gets more of what it wants, and less of what it does not want, at least for a while, until everything about the city’s affairs is revisited once again, as the various seasons of risk come around, each holding sway in turn. As we say in our working paper, clumsiness is why village communities in the Himalayas and Swiss Alps have remained viable over the centuries, without destroying either themselves (‘man’) or their environments (‘nature’) – sustainability par excellence, in other words.

So now we must ask: can cities be viable and sustainable in the same way as these mountain villages? In particular, how can the city’s built environment – the infrastructure that mediates between nature and man, the natural and human environments – be made resilient and adaptable, especially in an ecological sense? Thus might we possess this much prized attribute of systems behaviour in each of the natural, built, and human environments, and in a mutually reinforcing manner. What role might clumsiness have in all of this?

In closing our working paper, where we “connect the systemic dots” of our entire argument, we touch upon a computational foresight study in seeking a smarter urban metabolism for London. The fourfold typology of clumsiness is employed to define future target aspirations for the city (quantitatively expressed, under gross uncertainty). These should be the distant outcomes of the fourfold narratives of how the world is believed to work and what it is that each attaching vested interest much wants – and decidedly does not want. An inverse sensitivity analysis (redolent of a computational backcasting) identifies what is key (and what redundant) to the ‘reachability’ (or not) of each of the 4 sets of aspirations for the distant future. Imagine then the urine-separating toilet (UST) as the clumsy solution to a smarter metabolism for London – a smarter way, that is, of the city’s processing of the resource flows of water, energy, carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus passing through its social-economic life. Rather more grandly put, imagine instead the UST as a “privileged, non-foreclosing policy-technology innovation” for today!

Well now … if clumsiness is such a jolly good thing, what else might it do for us and our cities? We submit it promises the prospect of greater resilience and adaptability in the governance of innovation ecosystems, extending thus the lines of evidence recounted for re-invigoration of the industrial economy of NE Ohio in Katz & Bradley’s recent (2013) book Metropolitan Revolution. ‘Resilience’ and ‘ecosystem’ are (for now) ubiquitous in our everyday language. But no-one, as far as we are aware, has thought of applying the immensely rich notion of ecological resilience to orchestrating the creative and clumsy affairs of an innovation ecosystem. We are currently examining this.

Read the full report

Featured image by Peter McDermott. Used under Creative Commons.

For further information on the Foresight Future of Cities project visit: https://futureofcities.blog.gov.uk

48.05504316.352678

Jun 10, 2015 | Risk and resilience

By Leena Ilmola-Sheppard, IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis (ASA) Program

Crisis management problems are getting more complex and complicated, but at the same time, governments have less and less resources for their management. How can research help decision makers plan for the unplannable?

Last week in Geneva, I took part in a crisis management workshop for national decision makers organized by the OECD High Level Risk Forum and the Swiss Federation Chancellor While the meeting was very specific to national security and crisis management, I found some takeaway messages that are relevant to us researchers as well, especially for those of us that hope that to help decision makers make better decisions through modeling.

Mads Ecklon, Head of the Centre for Preparedness Planning and Crisis Management of the Danish Emergency Management Agency, used the figure above as a framework to explain crisis management. His message can also be applied to the development of any social system. Picture 1 describes the standard starting point of the modeling exercise. We are modeling one behavior and then analyze how the system performance develops in a controlled situation. Ecklon explained that potential futures are not so predictable: the crisis in hand can either be solved, solved only partially, not solved at all, or in the worst case the problem may escalate (you never know how a social system will react in the crisis situation—a small incident can turn into a massive riot). The challenge for both national level crisis managers and modelers is same; you have to take all of these potential developments into a consideration.

But what happens if a new, unexpected crisis pops up while all attention is focused on the initial problem? Such hard-to-predict events are often referred to as “black swan events.” Eclon said that their team has more frequently been seeing situations where, when attention is focused on the current crisis, a new, different or related, crisis develops and no one notices it. For example, in the UK in 2007, just when all the crisis management resources were invested in flooding crisis, foot and mouth disease broke out among cattle. The new phenomenon, Ecklon claimed, is that these crises are piling up and even if they are independent from each other, the joint impact can be disastrous.

Modeling black swan events

I think that this message is important for modelers as well. We may be very happy to model all the four windows of our comic strip. But how can we include new surprises and crises into an ongoing model? We should develop models that include different development trajectories triggered by a change in one of our variables, but simultaneously we should be able to account for several overlapping surprises.

In the meeting, national risk managers spoke about ”unknown unknowns,” low probability high impact risks–strange unforeseen animals like a black swan that jump on the plate just when we think that the situation is in some kind of control.

This kind of modeling challenge is fascinating from an academic perspective, but researchers’ intellectual hunger should not be the only reason to develop methods for these kinds of situations. From decision makers’ perspective, this is exactly the case where useful models are needed. The multiple simultaneous developments of the complex systems are difficult to capture even for the brightest of the crisis teams, but a model could manage a job very well.

Most of the IIASA models are large, integrated models that cover global systems. These models are not designed for digesting black swan sandwiches. The Danish crisis management team has a solution worth for benchmarking for this problem as well. They have a specific small team that is called a Pandora’s Cell. Pandora’s Cell is dedicated to anticipating, imagining, and scanning for potential not-so-obvious developments that should be taken into consideration in decision making. This dedicated team is needed because all the other resources available have been focused on the obvious events, as described in the square one of our comic strip.

Black swan events refer to those that are unpredictable and difficult to plan for. © Wrangel | Dreamstime.com – Black Swan Photo

Feb 11, 2015 | Risk and resilience

By Junko Mochizuki, IIASA Risk, Policy and Vulnerability Program

As economic losses due to natural disasters rise globally, there is an increasing consensus that the impacts of public and private investments on disaster risk must properly be monitored and evaluated. Such “risk-sensitive investment” is increasingly recognized as good practice in both public and private sector decision making. As we look beyond the Post-2015 development agenda, the incorporation of risk is increasingly becoming a crucial element to sustainable and resilience development throughout the world.

Risk reduction measures such as bamboo shelters and protected water sources can mitigate risks during and following a disaster ©EU/ECHO Malini Morzaria via Flickr

While risk sensitive investment will likely receive great fanfare at the World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction to be held in Sendai next month, the prospects for achieving such investments are still distant for many developing countries. Despite much recent progress to collect and analyze natural disaster damage, loss, and risk information globally, data quality remains largely poor for these countries. Many developing countries also lack the expertise to interpret and use such data effectively. Even when capacity exists at the technical staff level, political will and financial capacity may not be sufficient to use risk information tangibly and invest in risk reduction activities.

My participation at a recent workshop in Madagascar, the Training Program on Disaster Risk Assessment and Optimization of Public Investments in Reducing Economic Losses in January confirmed my sense of this inadequate on-the-ground reality. With a per capita GDP of approximately $460 per year, Madagascar is one of the poorest countries and, located in the western corner of the Indian Ocean, one of the most highly exposed to natural disaster risk. In 2008 for example, three consecutive cyclones caused more than $330 million in damage and losses. The annual average loss (AAL) from cyclone wind alone is estimated to be $74 million or nearly 1% of the country’s GDP. After two days of capacity-building training on risk assessment and investment decision-making tools such as IIASA’s Catastrophe Simulation (CATSIM) model and Probabilistic Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA), discussions by technical staff centered around how to fill the large gap between the reality of where they stand now and where they should be in the future.

At the workshop, the participants asked questions such as “How can we strengthen contingency funding and the mainstreaming of disaster risk reduction at the same time?” and “What can a cash stripped government do when donors themselves do not seem to allocate funding based on the tangible needs of a country’s natural disaster risks?”

Workshop in Madagascar. Credit: Junko Mochizuki

Given the unique constraints facing developing countries, solutions must be tailored to their specific needs, however much of the know-how and technological options that have worked in the developed world cannot be easily replicated in a country like Madagascar. There are no easy answers, but the participants’ earnest opinions certainly gave me a positive impression that they are serious about taking disaster risk into account in their development.

As we deliberate the post-2015 goals on climate change, disaster risk reduction, and sustainable development, it is vital that the international community consider these important questions: Given the unique constraints of developing countries, what can our state-of-the-art science produce as usable and useful information for the realities of their decision making? There are more dialogues to be had and research to be conducted incorporating their viewpoints. This workshop provided an important opportunity to exchange ideas and a glimpse into the real challenges of risk sensitive investment in the developing world.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 5, 2014 | Energy & Climate, Risk and resilience

By Reinhard Mechler & Thomas Schinko (IIASA) with Swenja Surminski (LSE)

(updated 17 December 2014)

As participants in the 20th Conference of the Parties to the Climate Convention (COP 20) in Lima strived to prepare the grounds for a comprehensive climate agreement expected for COP 21 in Paris, negotiators faced key questions that revolve around responsibility and burden sharing.

These questions are not new and have played a key role in the policy and academic discourse on climate change since the beginning of the UNFCCC process.

On the mitigation of emissions, the debate has circled around burden sharing: How should emission reductions be distributed among countries and what are the distributional consequences? On climate impacts and adaptation, the debate has centered on the question of who should pay for adaption and impacts in the global South, given that the global North has been responsible for the bulk of historic anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions and that the global South will be facing the most severe risks from climate change.

The 20th Conference of the Parties to the Climate Convention (COP 20) opened in Lima on December 1st with big fanfare. It is considered the key milestone event on the road to a comprehensive global deal on climate change that many hope will be struck in Paris in a year’s time. Photo Credit: UN Climate Change

As a partial response, the Green Climate Fund (CGF) was established at COP 16 in Copenhagen to assist developing economies in addressing climate change adaptation and mitigation. The GCF is currently being capitalized by industrialized and emerging economies with the aim of raising 100 billion USD by 2020. At the UN climate talks in Lima the CGF has achieved – thanks to last-minute pledges by several countries – its short term target of mobilizing at least 10 billion USD for the next four years.

Negotiations covering impacts and adaptation have further proceeded, among others, under the umbrella of the Warsaw Loss and Damage Mechanism (WIM), accepted at COP 19 in Warsaw after strong debate as to its meaning and nature- some suggest this mechanism should be part of adaptation, others want it to focus on residual risks that remain after adaptation efforts have been taken.

As a contribution to the WIM discourse, we recently suggested an approach organized around climate risk management, involving the principle of risk layering. We propose that the WIM can build on this principle to distinguish between risk layers to be managed and residual risk layers ‘beyond adaptation,’ thus involving both equity and efficiency aspects: (i) Equity in terms of financially supporting countries particularly vulnerable to climate change in their efforts to manage risks and deal with the burdens ‘beyond adaptation’; (ii) Efficiency in terms of helping to identify best practice for managing risk through well-designed risk prevention, preparedness and financing measures that address high and low frequency climate-related events.

We argue that the risk layering perspective may contribute to taking the WIM discourse over the apparent red negotiation lines if financial support is coupled with well-targeted risk management efforts – such as coordinated nationally through national platforms for disaster risk reduction,

Notions of risk management have been fundamental for the WIM. In Lima the parties discuss whether to accept a two-year work plan, which was put together with input from policy, science and practice. The work plan would give a strong role to risk management and, among others, would seek advice on “enhanced understanding of how comprehensive risk management can contribute to transformational approaches.”

Inauguration ceremony of COP20 in Lima. Credit: Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, Peru

Transformational risk management approaches have been promoted by the disaster risk management community over the last few years in seeking a better balance between pre-event risk management and post-event relief and reconstruction (currently 15% of overseas development assistance goes into pre-event efforts vs. 85% into post-event). As a case in point, regional risk pools (mostly covering climate-related risks) have been springing up in the Caribbean, Pacific, and Africa. These efforts are first and foremost focussed on mutually financing risk, but can also be seen as a first step to a comprehensive approach for reducing and financing risks.

For example, the African Risk Capacity (ARC) pool provides quick finance to provide relief after drought events, and has aimed at linking these efforts to improvements in response planning and early warning. Innovatively, the ARC, initially capitalized by donor support and country contributions, currently explores to set up an Extreme Climate Facility for raising funding for any losses that can be related to climate change and may endanger the solvency of the ARC.

The idea is to monitor variability in a composite index of weather indicators over time and understand whether this variability can be attributed to climate change, which would then lead to a pay-out to the fund from this facility. While promising, the link to attribution is a key scientific challenge, and a number of principled and implementation-related questions for this particular facility as well as for the WIM in general remain open. These open questions will need further attention by science, policy, practice and civil society in the coming months in order to help achieve progress on the Loss and Damage Mechanism.

Reference

Reinhard Mechler, Laurens M. Bouwer, Joanne Linnerooth-Bayer, Stefan Hochrainer-Stigler, Jeroen C. J. H. Aerts, Swenja Surminski & Keith Williges. 2014. Managing unnatural disaster risk from climate extremes. Nature Climate Change. March 26, 2014. http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v4/n4/full/nclimate2137.html

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 9, 2014 | Food & Water, Risk and resilience

By Robbert Biesbroek, Wageningen University and Research Centre, the Netherlands

Over the past years, a series of reports by the World Economic Forum have identified “failure to adapt to climate change” as being of highest concern to society. But in practice, what does adaptation to climate change mean? What makes adaptation particularly challenging for those policymakers, consultants, businesses and other practitioners working on adaptation in practice? An often heard answer is, “Because there are barriers to adaptation.”

The storm surge barrier Oosterschelde nearby Neeltje Jans in The Netherlands. With its low elevation and long coastline, the Netherlands is particularly sensitive to sea level rise, and has taken an early start to climate adaptation planning (Photo: Shutterstock)

In a recent study, we identified numerous examples of barriers to adaptation encountered by practitioners across the globe. These barriers to adaptation emerge from all angles and direction; they can be institutional (e.g. “rigid rules and norms”) resources (e.g. “lack of money”, “uncertain knowledge”) social (e.g. “no shared problem understanding”), cognitive (e.g. “ignorance”, “apathy”).

As scholars, we have proven to be very good in making lists of barriers to adaptation, but rather poor in understanding where these barriers come from, what the concept of “barriers” means to practitioners, why barriers are mentioned at all, or how barriers can be dealt with in an meaningful way. In a follow-up study, colleagues and I argued that listing barriers in isolation from their decision-making context is an interesting first step, but has hardly provided insights in the openings needed to adequately deal with them. In fact, they often lead to a linear argumentative logic – “Not enough money? Then we need more money or we need to spend the money we do have more wisely!” Such superficial advice is not particularly useful to practice.

By delving deeper in the questions of why adaptation is challenging, we found that what practitioners mention as barriers are mere simplifications of what really happened. Barriers become metaphors that capture people’s lived experience and evaluation of the process into easy to communicate messages – e.g. “no money.” We can argue about whether this is truly a barrier, because their interpretation stems from a complex and dynamic chain of events that only makes sense to those that were actively involved. By putting labels on these events, they automatically become static, therefore lacking the necessary insights in the dynamics that caused the process to become challenging and provide the necessary openings to intervene. We concluded that using barriers as units of analysis to explain why adaptation is challenging is therefore flawed: the analytical challenge is to go beyond barriers in search of the explanatory causal processes, or so-called causal mechanisms.

An example: In our study, we identified 24 different barriers encountered by practitioners during the design and implementation of an innovative adaptation measure for temporal water storage in the city center of Rotterdam, the Netherlands. By going beyond this list, we uncovered three underlying mechanisms that explain why the first attempt to implement the so-called “water plaza” failed. One mechanisms, we called the risk-innovation mechanism—which is basically a miscommunication about risk that leads to public outcry.

An illustration of the proposed water plaza in the Netherlands. (Image: De Urbanisten)

In this case, the government took a technocratic stance in communicating the risks and benefits of the project. Meanwhile the citizens, as mutual bearers of the risks, wanted to negotiate about what levels of risk were acceptable. By taking such stance the government avoided a moral debate about the risk of the innovation (the innovation was “adaptation”), but the result was angry citizens who to rebelled against the project and the municipal government. This analysis provided openings to change communication strategies – an intervention the project team used successfully in next stages of the process.

Insights from this study have broader implications. It explains, for example, why existing guidelines to support practitioners to overcome barriers to adaptation have not worked well: As I explored more deeply in my thesis, these guidelines are simply not tailored to the real reasons why adaptation is challenging. We can continue to make endless lists of barriers, but to advance theoretically and conceptually, and to provide meaningful strategies to intervene in practice, we need to rethink how we use the concept of “barriers to adaptation” and start searching for underlying causal mechanisms.

Robbert Biesbroek completed his PhD in January 2014, supervised by IIASA Director General and CEO Prof. Dr. Pavel Kabat.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

References:

(1) Biesbroek, G. R., Klostermann, J. E. M., Termeer, C. J. A. M., & Kabat, P. (2013). On the nature of barriers to climate change adaptation. Regional Environmental Change, 13(5), 1119-1129.

(2) Biesbroek, G. R., Termeer, C. J. A. M., Klostermann, J. E. M., & Kabat, P. (2014). Rethinking barriers to adaptation: mechanism based explanation of impasses in the governance of an innovative adaptation measure. Global Environmental Change 26, (1) 108-118

(3) Biesbroek, G. R. (2014). Challenging barriers in the governance of climate change adaptation. Ph.D. thesis, Wageningen: Wageningen University.

Jun 17, 2014 | Risk and resilience

By Junko Mochizuki, IIASA Risk, Policy, and Vulnerability Program

Catastrophic natural disasters such as Typhoon Haiyan of 2013 and Thailand’s flood of 2011 have highlighted the need for improved preparedness and proactive planning in developing countries. As population and economic activities continue to grow in hazard-prone areas, the economic costs of natural disasters are expected to rise globally, threatening the prospects for poverty alleviation and sustainable development.

Workshop participants learn to use IIASA’s CATSIM tool.

Cambodia is no exception. Frequent natural disasters continue to strain the country’s meager fiscal resources. Flood-related expenditure in particular has increased in recent years. In 2013, the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, in charge of major road construction, diverted approximately 20% of its non-maintenance budget for recovery and reconstruction. Ministry of Rural Development, in charge of rural sanitation, health and agricultural projects, faces similar constraints. Some of the costliest disasters have occurred in recent years: the 2013 flood cost $1 billion and the 2011 flood $624 million in damage and losses. The World Bank recently estimated that the annual average expected cost of natural disasters in Cambodia is approximately 0.7% of GDP.

On June 10-11, I participated in an IIASA workshop on this topic in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, along with IIASA researcher Keith Williges. Our goal was to train Cambodian policymakers on the concept of disaster risk and need for better fiscal preparedness, using IIASA’s CATSIM model. Like many low-income countries, Cambodia’s ability to access resources through taxation and external loans is limited. Using CATSIM, policymakers can evaluate alternative options for preparedness including hazard mitigation and reserve fund and assess how further accumulation of economic assets may raise risk in the longer term.

In 2011, Cambodia experienced heavy flooding after strong typhoons and heavy rain. Photo credit: Thearat Touch EU/ECHO

Risk-based planning is still uncommon globally and particularly so in developing countries like Cambodia. Year after year, scarce resources are wasted because national and local policymakers do not have access to good risk information such as risk maps and timely weather forecasts. This could change, however, as detailed risk maps are becoming available and a new standard operation procedure for early warning system is now being prepared under this project. The CATSIM workshop has also familiarized policymakers with the concept of economic and fiscal risk of natural disasters.

While policymakers understand the potential costs rising from natural disasters, the real challenge is to link such risk information strategically. Without concrete advice on how risk maps can prioritize budget allocation, for example, it is unlikely that decision makers will change their old practice of non-risk based planning. In addition to quantifying and communicating economic, social, and environmental benefits of risk reduction and management, further barriers including financial, institutional and cognitive gaps must also be addressed. Bridging science with policy implementation requires strategic linking, and the CATSIM training marked an important first step for improved risk-based planning and co-production of knowledge in Cambodia.

More information:

You must be logged in to post a comment.