Jul 6, 2017 | Risk and resilience

An interdisciplinary research project explores glo-cal entanglements of power and nature in 18th century Vienna

By Verena Winiwarter, Guest Research Scholar, IIASA Risk and Resilience Program, and Professor, Centre for Environmental History, Alpen-Adria-Universitaet Klagenfurt.

Nowadays, rulers turn to primetime TV events to demonstrate their power, be it putting men on the moon, testing missiles, or building walls. When the kings of France, in particular Louis XIV and XV, built Versailles, they had the same goals: To claim their leading role in Europe and make their mastery of nature and their subjects visible for all.

In the 1700s, the Austro-Hungarian Empire had to pull off a comparable feat, in particular as Emperor Charles VI had a huge constitutional problem: His only surviving child, a smart and pretty daughter, was not entitled to the throne. Only men could be emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. So while eventually, an international agreement allowed young Maria Theresia to succeed him, her position was clearly weak and would become contested right after her father’s death.

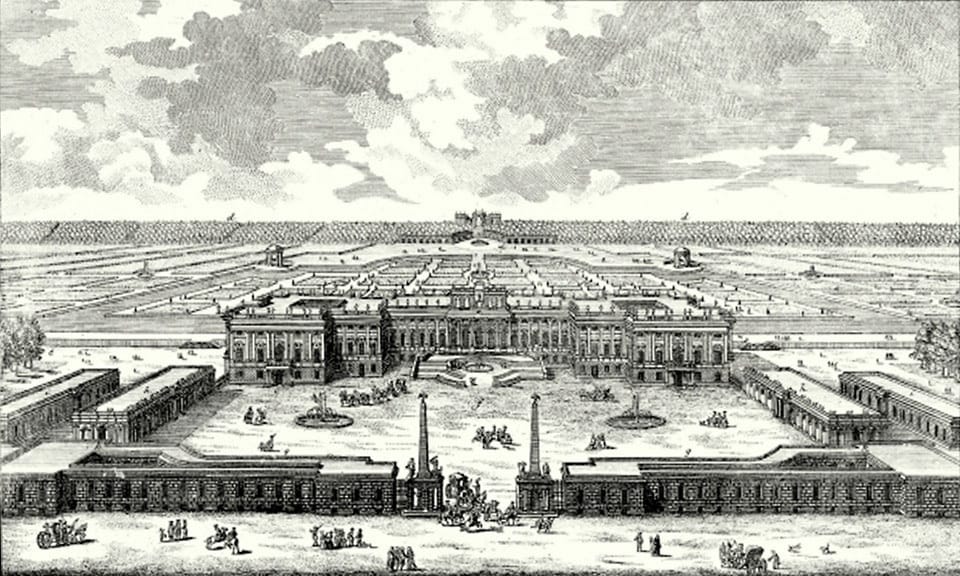

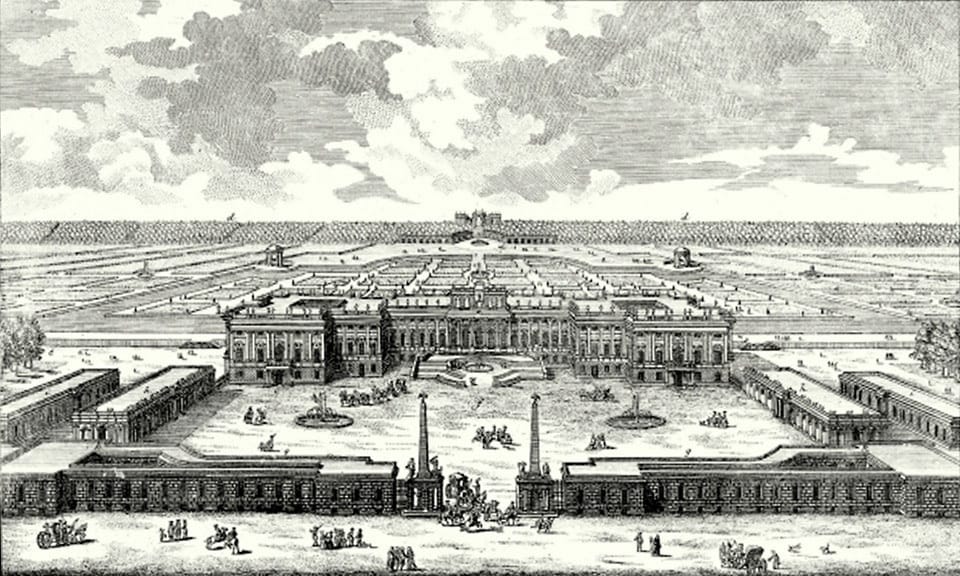

The construction of Vienna’ Schönbrunn Palace, and the taming of the river that flows by it, served as an international declaration of power by the Habsburgs and helped secure Maria Theresia’s position. Vienna, the Habsburg capital, already sported a summer palace in the game-rich riparian area to the west of the city center, close to a torrential, but rather small tributary of the Danube, the Wien River. Here, the leaders decided, a palace dwarfing Versailles should be built. One of the most famous architects of his time, J.B. Fischer von Erlach originally designed a grandiose structure that could never have been carried out. But it staked a claim and when seven years later, a more realistic plan was submitted, it became the actual blueprint of what today is one of Vienna’s most famous tourist sites.

Fischer v. Erlach’s second, more feasible design for Schönbrunn Palace (Public Domain | Wikimedia Commons)

While the kings of France built in a swamp and overcame a dearth of water by irrigation, the Habsburgs’ choice offered another opportunity to show just how absolute their rule was: the torrential Wien River had damaged the walls of the hunting preserve with its then much smaller palace several times. Putting the palace right there, into a dangerous spot, allowed the house of Habsburg to prove that their engineers were in control.

The flamboyant new palace was deliberately placed close to the Wien River, necessitating its local regulation. This had repercussions for those living up- and downstream, as flood regimes changed. Not all such change was beneficial, as constraining the river’s power meant that it found outlets elsewhere. In this case, European power struggles affected the course of a river, putting a strain on locals for the sake of global status.

In the 19th century, effects of global events and structures played out in favor of local health, when it came to building sewers along the by then heavily polluted Wien River. The 1815 eruption of the Tambora volcano in Indonesia led to unusually heavy rains during the otherwise dry season and the proliferation of cholera, which British colonial soldiers brought to Europe. A cholera epidemic hit Vienna in 1831/32, creating momentum to finally build a main sewer along Wien River. The first proposals for a sewer date back to 1792; they were renewed in 1822, but due to urban inertia, the sewer was not built. Thousands of deaths (18,000 in recurring outbreaks between 1831-1873) called for a response, and from 1831 onwards, collection canals were built.

A global constellation had first affected locals negatively, but with long-term positive outcomes of much cleaner water.

We uncovered these stories of the glo-cal repercussions of Wien River management during the FWF-funded project URBWATER (P 25796-G18) at Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt with the joint effort of an interdisciplinary team. We have shown in several publications how urban development was intimately tied to the bigger and smaller surface waters and to groundwater availability, telling a co-evolutionary environmental history.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dhvptRsuJcI

The overall development of the dammed and straightened, then covered river can be seen in science-based videos by team member Severin Hohensinner for 1755. At 2:00 in the video, the virtual flight nears Schönbrunn on the right bank, with the regulation measures visible as red lines. A comparison between 1755 and 2010 is also available. Both videos start with an aerial view of downtown Vienna and then turn to the headwaters of the Wien, progressing towards the center with the flow.

More on the project, including links to publications and images are available at http://www.umweltgeschichte.uni-klu.ac.at/index,6536,URBWATER.html

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 29, 2017 | Citizen Science, Risk and resilience

By Wei Liu, IIASA Risk and Resilience Program

What do Rajapur, Nepal; Chosica, Peru; and Tabasco, Mexico all have in common? Flooding: these areas are all threatened by floods, and they also face similar knowledge gaps, especially in terms of local level spatial information on risk, and the resources and the capacities of communities to manage risk.

To address these gaps, I and my colleagues at IIASA, in collaboration with Kathmandu Living Labs (KLL) and Practical Action (PA) Nepal are building on our experiences in Nepal’s Lower Karnali River basin to support flood risk mapping in flood-prone areas in Peru and Mexico.

Recent developments in data collection and communication via personal devices and social media have greatly enhanced citizens’ abilities to contribute spatial data, called Crowdsourced Geographic Information (CGI) in the mapping community. OpenStreetMap is the most widely used platform for sharing this free geographic data globally, and the fast growing Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team has developed CGI in some of the world’s most disaster-prone and data-scarce regions. For example, after the 2015 Nepal Earthquake, thousands of global volunteers mapped infrastructure across Nepal, greatly supporting earthquake rescue, recovery, and reconstruction efforts.

Today there is excellent potential to engage citizen mappers in all stages of the disaster risk management cycle, including risk prevention and reduction, preparedness and reconstruction. In this project, we have successfully launched a series of such mapping activities for the Lower Karnali River basin in Nepal starting in early 2016. In an effort to share the experience and lessons of this work with other Zurich Global Flood Resilience Alliance field sites, in March 2017 we initiated two new mapathons in Kathmandu, with support from Soluciones Prácticas (PA Peru) and the Mexican Red Cross, to remotely map basic infrastructure such as buildings and roads, as well as visible water surface, around flood-prone communities in Chosica, Peru and Tobasco, Mexico.

March 17th, 2017, staff and volunteers conducting remote mapping at Kathmandu Living Labs @ Wei Liu | IIASA

Prior to our efforts very few buildings in these areas were identified on online map portals, including Google Maps, Bing Maps, and OSM. Through our mapathons, dozens of Nepalese volunteers mapped over 15,000 buildings and 100 km of roads. The top scorer, Bishal Bhandari, mapped over 1,700 buildings and 6 km of roads for Chosica alone.

Having the basic infrastructure mapped before a flood event can be extremely valuable for increasing flood preparedness of communities and for local authorities and NGOs. During the period of the mapathons, the Lima region in Peru, including Chosica, was hit by a severe flood induced by coastal El Niño conditions. Having almost all buildings in Chosica mapped on the OSM platform now makes visible the high flood risk faced by people living in this densely populated area with both formal and informal settlements. These data may support conducting a quick damage assessment, as suggested by Miguel Arestegui, a collaborator from PA Peru during his visit to IIASA in April, 2017.

Recognizing the value of crowdsourced spatial risk information, we are working closely with partners, including OpenStreetMap Peru, to mobilize the creativity, technical know-how, and practical experience from the Nepal study to Latin America countries. Collecting such information using CGI comes with low cost but high potential for modeling and estimating the amount of people and economic assets potentially being affected under different future flood situations, for improving development and land-use plans to support disaster risk reduction, and for increasing preparedness and helping with allocating humanitarian support in a timely manner after disaster events.

Having the basic infrastructure mapped before a flood event can be extremely valuable for increasing flood preparedness of communities and for local authorities and NGOs. During the period of the mapathons, the Lima region in Peru, including Chosica, was hit by a severe flood induced by coastal El Niño conditions. Having almost all buildings in Chosica mapped on the OSM platform now makes visible the high flood risk faced by people living in this densely populated area with both formal and informal settlements. These data may support conducting a quick damage assessment, as suggested by Miguel Arestegui, a collaborator from PA Peru during his visit to IIASA in April, 2017.

Recognizing the value of crowdsourced spatial risk information, we are working closely with partners, including OpenStreetMap Peru, to mobilize the creativity, technical know-how, and practical experience from the Nepal study to Latin America countries. Collecting such information using CGI comes with low cost but high potential for modeling and estimating the amount of people and economic assets potentially being affected under different future flood situations, for improving development and land-use plans to support disaster risk reduction, and for increasing preparedness and helping with allocating humanitarian support in a timely manner after disaster events.

Flood-inundated houses and local railway in Chosica, Peru, 18/03/2017 @ Miluska Ordoñez | Soluciones Prácticas

The United Nation’s Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction states that knowledge in “all dimensions of vulnerability, capacity, exposure of persons and assets, hazard characteristics and the environment” needs to be leveraged to inform policies and practices across all stages of the disaster risk management cycle. CGI has a great potential to involve citizens from around the world to help fill this critical knowledge gap. These pilot mapathons conducted between Nepal and Latin America are promising examples of supporting community flood resilience through the mobilization of CGI via international partnerships within the Global South.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 27, 2017 | Postdoc, Risk and resilience

By Adam French – Peter E. de Jánosi Postdoctoral Scholar Risk and Resilience and Advanced Systems Analysis Programs

In mid-January, I found myself calling upon rusty rock climbing skills to scramble up a steep side canyon of Peru’s Rimac River valley. I was with a group of engineers and local municipal officials on the way to assess disaster reduction infrastructure that had been installed in early 2016 against the threat of a strong El Niño-enhanced rainy season. The Swiss-made barriers we were going to see, which resembled giant steel spider webs stretched across the streambeds, had been constructed in multiple locations in the Rimac watershed to reduce the destructive impacts of the region’s recurrent but unpredictable huaicos—powerful debris flows that form when precipitation runoff mixes with loose rock and other material on unstable slopes. The 2015-16 El Niño did not live up to its forecasted intensity in Peru, and the barriers went untested until heavy rains in early 2017 unleashed a series of huaicos on the Rimac valley, damaging homes and flooding roadways. Where the barriers were installed, however, no major impacts had been reported, and we were eager to see if the infrastructure had made a difference.

Engineers discuss hazard reduction infrastructure above Chosica, Peru. ©Soluciones Prácticas, Abel Cisneros (Click for more photos)

Most of the time, the Rimac valley looks more like a lunar landscape than a flood-risk hotspot. Yet with only a few millimeters of rain in the surrounding highlands, this arid region becomes extremely vulnerable to huaicos. Located between the sprawling cityscape of Lima—the planet’s second largest desert city—and the lush foothills of the central Andes, the middle reaches of the Rimac watershed have been settled rapidly over recent decades, often without effective zoning regulations to restrict occupation in even the most hazard-prone areas.

I had not planned to work in the Rimac basin when I moved to Austria to take up a postdoctoral position in late 2015. While my research includes the study of climate change-related risk in Peru’s Cordillera Blanca (the world’s most extensively glaciated tropical mountain range), I came to IIASA to focus on watershed-level governance and the implementation of the Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) paradigm. Yet as a Spanish speaker with extensive experience in Peru, I was well suited to get involved in IIASA’s activities in the Rimac valley as part of the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance Project. This project, which includes close collaboration with the NGO Practical Action in Peru and Nepal, supports measures to understand and address the underlying drivers of flood risk and to move beyond short-term disaster preparedness and response towards transformative actions that build long-term capacity and resilience.

As part of IIASA’s Flood Resilience team, my work in the Rimac valley has included activities ranging from evaluating El Niño preparations to conducting interviews with public authorities and local residents living in the Rimac basin. This fieldwork is just part of our project’s efforts to identify the systemic components of flood risk and vulnerability in the region and to promote productive exchanges between residents, policymakers, and the scientific community through participatory research and innovative approaches such as serious gaming.

“Flood Risk Zone,” Ate, Peru. ©Soluciones Prácticas. Click for more photos.

In addition to building expertise in a new setting, my involvement in this work has helped me better incorporate risk-focused systems thinking into my broader research agenda—a perspective that is too often overlooked in integrated resource planning. An example of how my research interests are converging within this project is through the promotion of a risk-management working group to advise the multi-sectorial watershed council in charge of IWRM planning in the Rimac valley. The establishment of this working group and the participation of project partners at Practical Action in its activities should mark an important step in bringing lessons from the Flood Resilience project regarding links between disaster risk reduction, economic development, and community resilience to bear on watershed planning in the Rimac basin. More broadly, we hope these insights will influence policy making in other settings in Peru and beyond that face similar challenges in handling risk management and economic development as intricately linked and co-dependent governance processes.

Returning to our January field inspection, we found that one of the new barriers had been put to the test. The structure had captured several tons of debris, protecting a neighborhood that had been devastated by a huaico in 2015, and local authorities were already discussing the potential to build additional barriers to guard their community. While I celebrated this outcome with them, as I look to the future and the goals of the Flood Resilience Alliance, I am hopeful that such infrastructural interventions will be just one aspect of comprehensive plans for hazard reduction, with long-term risk management actions increasingly seen as a vital component of watershed-level planning and governance.

More information

IIASA, Zurich, Wharton, Practical Action: Flood Resilience Partnership

Flickr photo album: Rimac River valley, Peru – Fieldwork

Flood Resilience Portal

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 8, 2017 | Risk and resilience

By Junko Mochizuki Research Scholar, Risk and Resilience Program

After a 9.0 magnitude earthquake and subsequent tsunamis struck the northeast of Japan on March 11, 2011, large-scale destruction of the coastal communities, including nuclear accidents, turned into a political maelstrom. Debates over the country’s alternative energy futures became intense; worries over ailing energy infrastructure, public safety, and the lack of transparency and accountability led to the most extensive restructuring of its power sector in the country’s recent history.

Against this backdrop, renewable energy was heralded as one of the important solutions: A new nation-wide Feed-in-Tariff (FIT) was introduced in July 2012, replacing the Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), which many had perceived, until then, as largely inadequate.

Nearly six years have passed since. Japan’s reconstruction, originally envisioned to last for 10 years, is now in its latter phase. The coastal communities are slowing recovering, with many focused on the idea of ”building back better.” We now hear less about the country’s energy future in the national and international media. But less documented is how well these communities are performing in terms of the ambitious reconstruction plans that they had proposed.

The 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster led to major destruction in Northeast Japan. But did it also bring an opportunity to “build back better?” ©mTaira | Shutterstock

This was the context in which my colleague Stephanie E. Chang and I began our research titled Disaster as Opportunity for Change, recently published in the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. We evaluated renewable energy transition trends in the 30 coastal communities in Tohoku, Japan from 2012-2015. We focused on energy transition as one measurable dimension of ”building back better (BBB),“ because this is a popular concept that is often talked about, but rarely analyzed through empirical modelling.

In this study, we sought to answer three simple questions. First, are the disaster-affected regions really “building back better?” Have they introduced more renewable energy than the rest of Japan?. Second, why did some communities achieved greater renewable energy transition than others during recovery? Third, what was the role of government policy? We were interested in answering these questions through quantitative analysis, instead of an in-depth case study, since such in-depth analyses are rare in the field of disaster recovery.

In a reconstruction study, we typically need about 10 or more years to make major conclusions. Since we did our study in year six, this study doesn’t provide the final answer, but rather whether the disaster led to opportunity to build back better.

Our research indicated some clues in answering the above three questions, but many puzzles remain. First, it was clear that the disaster-affected regions achieved a greater transition to renewable energy, particularly in both small and mega-solar adoption. Other renewables including wind and geothermal are lagging due to many factors such as more complex approval processes. We focused our analysis on energy transition, measured in terms of per capita approved renewable capacity, as opposed to indicators such as installed capacity or power generated, since the latter depend on many factors such as the readiness of grid systems in accommodating intermittent renewables.

We also found that the relationship between a transition to renewable energy and the extent of disaster damage, and other post-disaster changes such as number of houses being relocated, appears to be non-linear. This means that the destruction caused by disasters, and subsequent decisions to relocate population, provided at least some momentum for wider societal change. Clearly, when communities experience very large destruction or extensive change such as land-use adjustment, this can overwhelm the local capacity to implement broader changes such as major investments in renewable energy. Balancing competing reconstruction demands is, therefore, an important policy question that must be dealt with, most ideally, prior to any large-scale disasters.

Japan is building mega solar installations like this one in the region affected by the tsunami and earthquake ©SE_WO | Shutterstock

Third, our results remain somewhat inconclusive as to the contribution of government policy. Counter-intuitively, communities having renewable energy plans prior to 2011 adopted significantly less solar energy after the Tohoku disaster. Statistical modeling such as ours tells little about how different aspects of national and prefectural policies have fostered or hindered local energy transitions and these are better answered through other means such as in-depth interviews.

Overall, we find potentially complex drivers of “building back better” and we hope that this study motivates further systematic studies of societal change in the context of post-disaster reconstruction. Of course, a better articulation of what policies work in promoting change and why will also help foster the sustainability transition even without the impetus of a disaster.

Reference

Mochizuki J & Chang S (2017). Disasters as Opportunity for Change: Tsunami Recovery and Energy Transition in Japan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.01.009. (In Press)

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 12, 2017 | Citizen Science, Risk and resilience

By Ian McCallum, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Communities need information to prepare for and respond to floods – to inform risk reduction strategies and strengthen resilience, improve land use planning, and generally prepare for when disaster strikes. But across much of the developing world, data are sparse at best for understanding the dynamics of flood risk. When and if disaster strikes, massive efforts are required in the response phase to develop or update information about basic infrastructure, for example, roads, bridges and buildings. In terms of strengthening community resilience it is important to know about the existence and location of such features as community shelters, medical clinics, drinking water, and more.

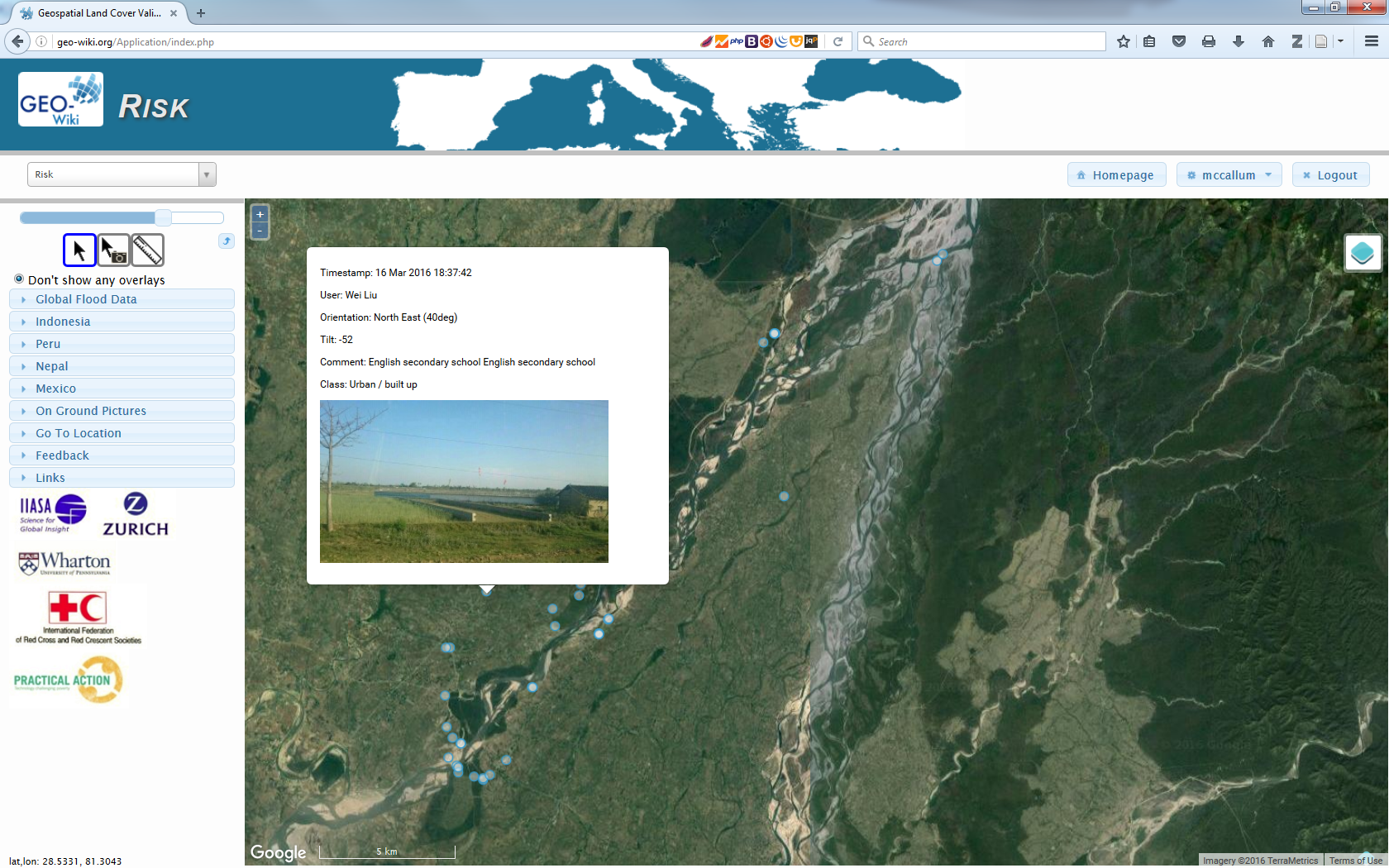

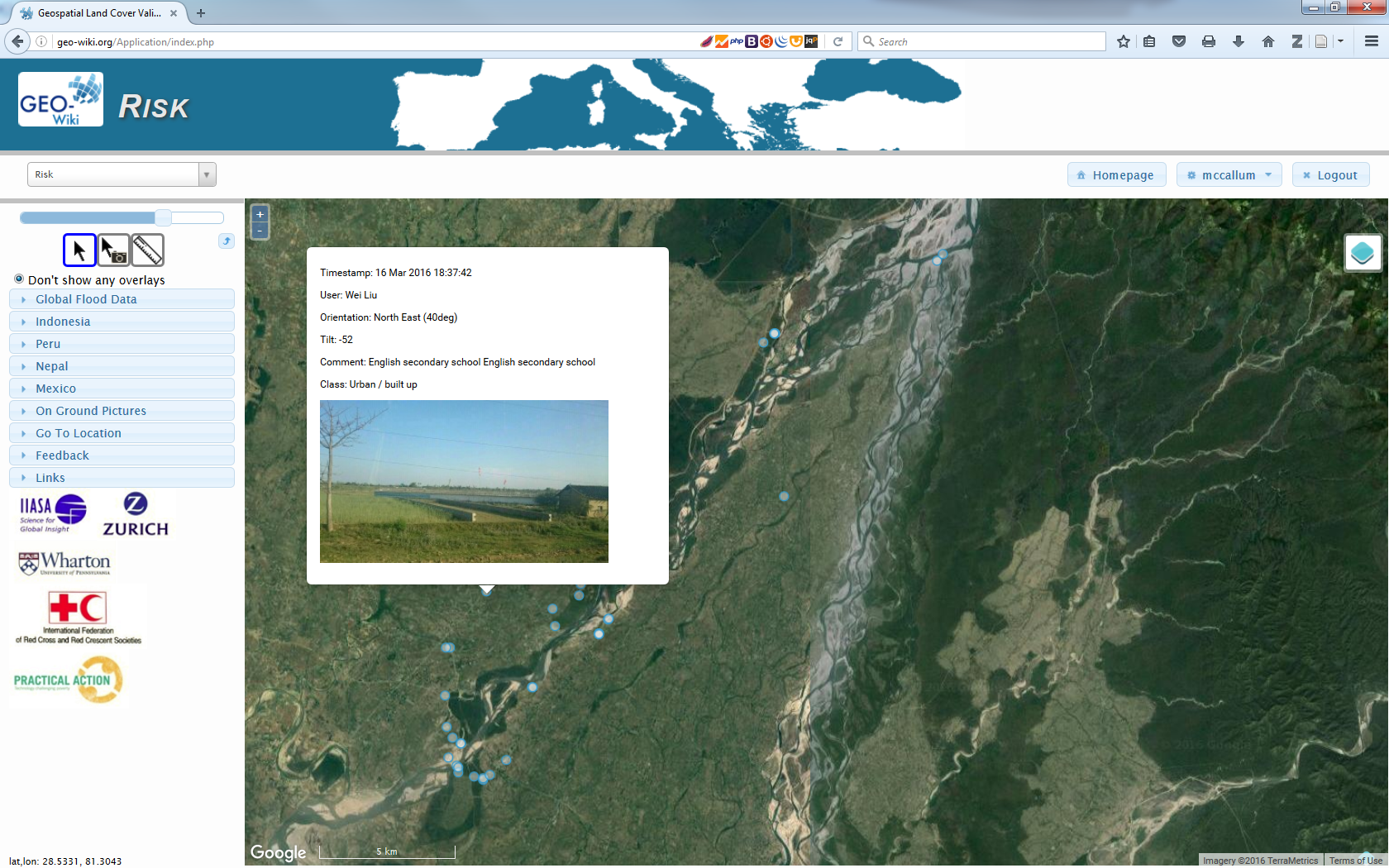

The risk Geo-Wiki platform

The Risk Geo-Wiki is online platform established in 2014, which acts not only as a repository of available flood related spatial information, but also provides for two-way information exchange. You can use the platform to view available information about flood risk at any location on the globe, along with geo-tagged photos uploaded by yourself or other users via a mobile application Geo-Wiki Pictures. The portal is intended to be of practical use to community leaders and NGOs, governments, academia, industry and citizens who are interested in better understanding the information available to strengthen flood resilience.

The Risk Geo-Wiki showing geo-tagged photographs overlaid upon satellite imagery across the Karnali basin, Nepal. © IIASA

With only a web browser, and a simple registration, anyone can access flood-related spatial information worldwide. Available data range from flood hazard, exposure and risk information, to biophysical and socioeconomic data. All of this information can be overlaid upon satellite imagery or OpenStreetMap, along with on-ground pictures taken with the related mobile application Geo-Wiki Pictures. You can use these data to understand the quality of available global products or to visualize the numerous local datasets provided for specific flood affected communities. People interested in flood resilience will benefit from visiting the platform and are welcome to provide additional information to fill many of the existing gaps in information.

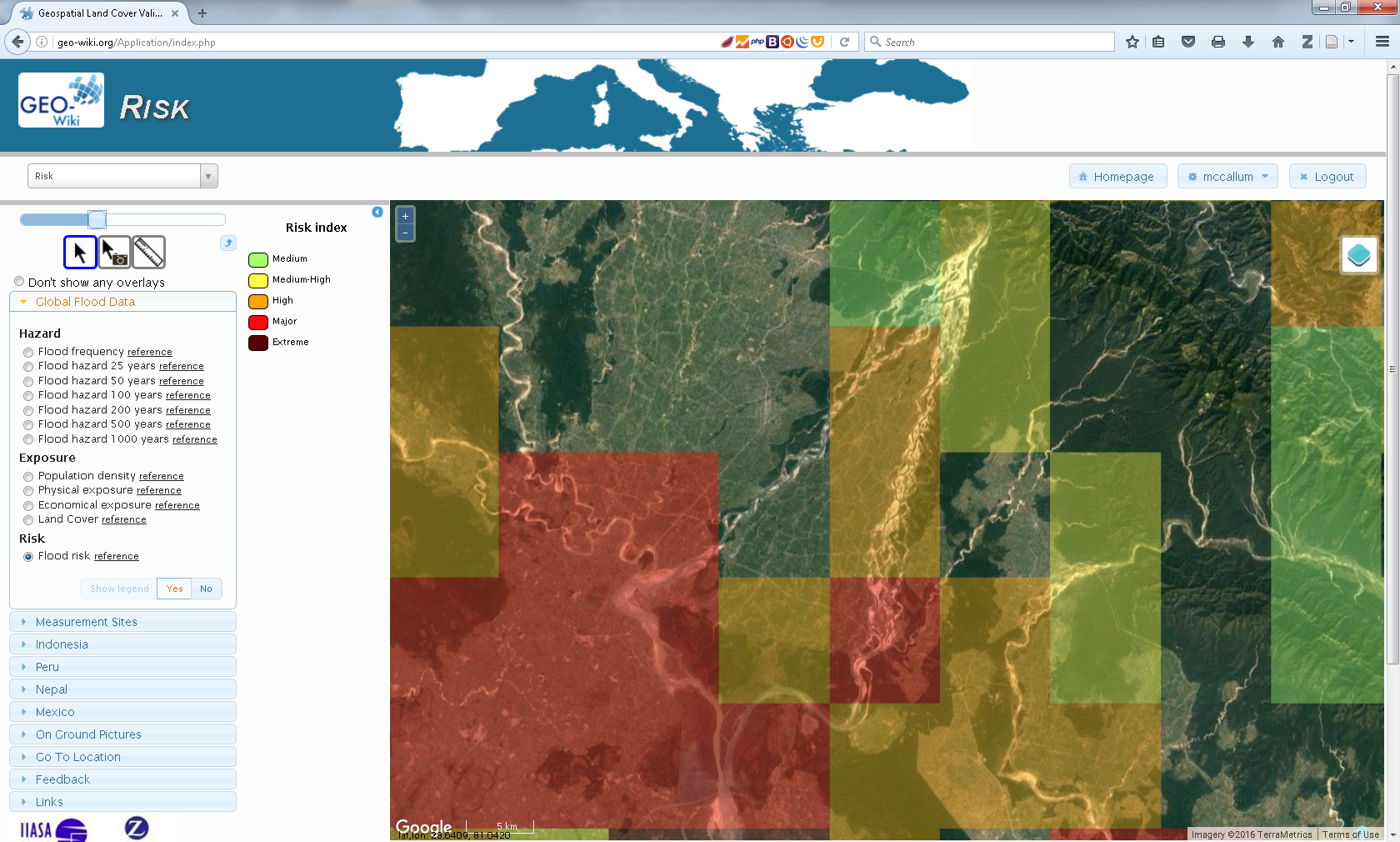

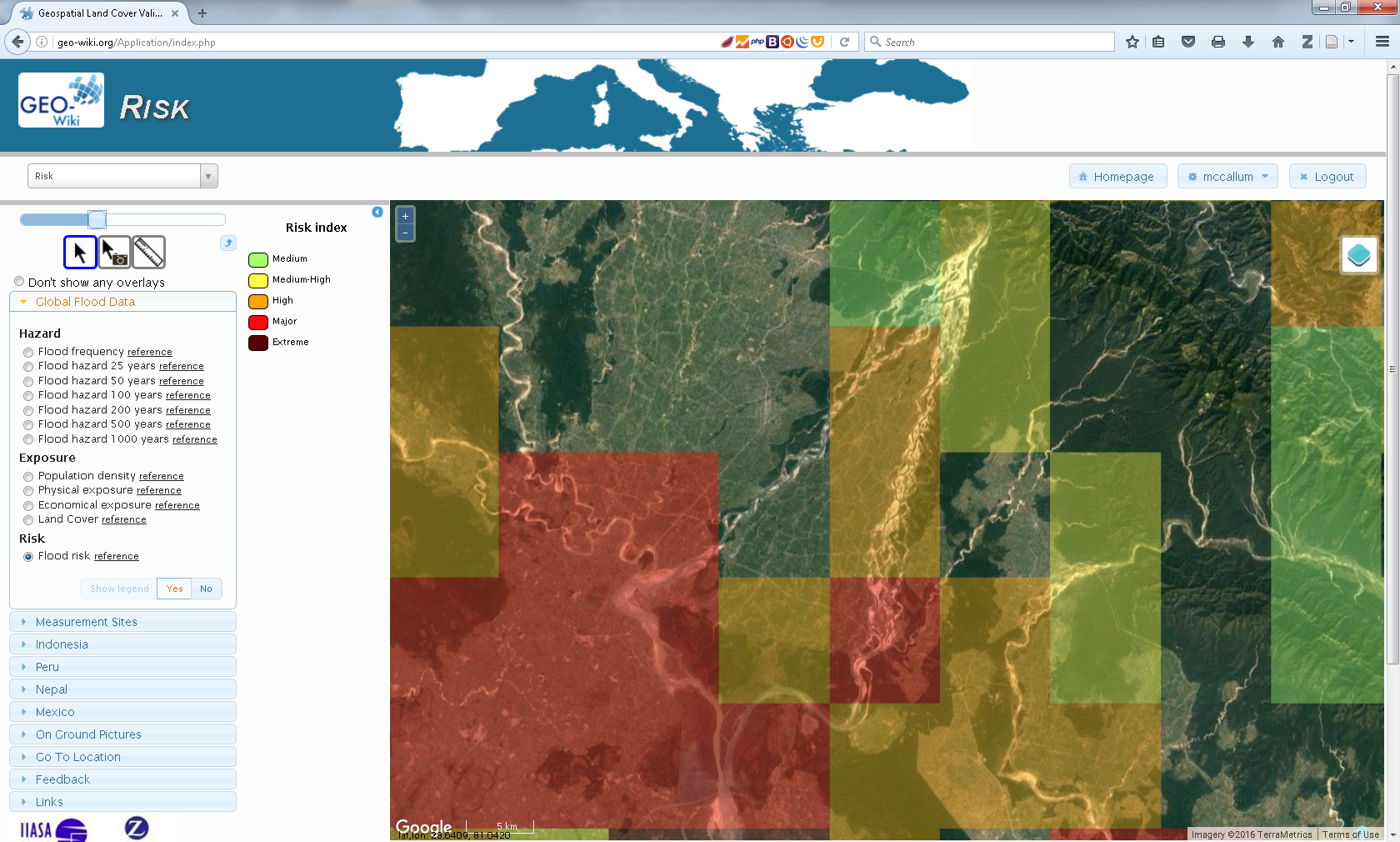

Flood resilience and data gaps

One of the aims of the Risk Geo-Wiki is to identify and address data gaps on flood resilience and community-based disaster risk reduction. For example, there is a big disconnect between information suitable for global flood risk modelling and that necessary for community planning. Global modelers need local information with which to validate their forecasts while community planners want both detailed local information and an understanding of their communities in the wider region. The Flood Resilience Alliance is working with many interested groups to help fill this gap and at the same time help strengthen community resilience against floods and to develop and disseminate knowledge and expertise on flood resilience.

The Risk Geo-Wiki showing modelled global flood risk data overlaid at community level. While this data is suitable at the national and regional level, it is too coarse for informing community level decisions. © IIASA

Practical applications for local communities

Already, communities in Nepal, Peru, and Mexico have uploaded data to the site and are working with us on developing it further. For local communities who have uploaded spatial information to the site, it allows them to visualize their information overlaid upon satellite imagery or OpenStreetMap. Furthermore, if they have used Geo-Wiki Pictures to document efforts in their communities, these geo-tagged photos will also be available.

Community and NGO members mapping into OSM with mobile devices in the Karnali basin, Nepal. © Wei Liu, IIASA

In addition to local communities who have uploaded information, the Risk Geo-Wiki will provide important data to others interested in flood risk, including researchers, the insurance industry, NGOs, and donors. The portal provides a source of information that is both easily visualized and overlaid on satellite imagery with local images taken on the ground if available. Such a platform allows anyone interested to better understand flood events over their regions and communities of interest. It is, however, highly dependent upon the information that is made available to the platform, so we invite you to contribute. In particular if you have geographic information related to flood exposure, hazard, risk and vulnerability in the form of images or spatial data we would appreciate you getting in contact with us.

About the portal:

The Risk Geo-Wiki portal was established by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in the context of the Flood Resilience Alliance. It was developed by the Earth Observation Systems Group within the Ecosystems Services and Management Program at IIASA.

Further information

- Risk Geo-Wiki

- Collection of geo-tagged photos with Geo-Wiki Pictures

- Mapping flood resilience in rural Nepal

- Flood Resilience Portal

- McCallum, I., Liu, W., See, L., Mechler, R., Keating, A., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., Mochizuki, J., Fritz, S., Dugar, S., Arestegui, M., Szoenyi, M., Laso Bayas, J.C., Burek, P., French, A. and Moorthy, I. (2016) Technologies to Support Community Flood Disaster Risk Reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 7 (2). pp. 198-204.http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/13299/

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 29, 2016 | Risk and resilience

By Nadejda Komendantova, IIASA Risk and Resilience Program

A transition to new energy sources—whether renewable, nuclear, or shale—does not just depend on technical availability and economic feasibility. In order for new projects to succeed, human factors, such as public and social acceptance, and willingness to use technology or to pay for it, are essential but often overlooked. It is important to understand these factors, because differences in views and perceptions of technology risks, benefits, and costs might lead to conflicts that could threaten the success of new projects.

Conflicts often appear between two or more parties with incompatible goals, different interests, or different risk perceptions, which can develop into either cooperation or conflict. For example, public opposition can lead to cancellation or delay of a planned project, and differences in views and risk perceptions can result in conflicts among different stakeholder groups. At the same time, if policymakers take into account this heterogeneity of views, the knowledge on the ground can lead to a better implementation of energy projects with more benefits for society and a smaller impact on the environment and hosting communities.

Row of high voltage pylons in the desert of Wadi Rum, Jordan ©Pierre Brumder | Adobe Stock Photo

An energy transition is currently taking place in the Middle East and North Africa. The region faces a number of challenges such as rising energy demand, unstable energy imports, increasing pressure on environmental resources, expectations of socioeconomic development, and political transformation. Morocco, Jordan, Tunisia, and other countries in the region are discussing new electricity infrastructure. Although large-scale deployment of renewable energy sources receives political support in this discussion, fossil fuels, and new emerging technologies such as shale oil and nuclear power are two prominent alternatives in the countries’ national development plans.

For this energy transition to succeed, policymakers in the region must adopt an adaptive and inclusive governance approach, which addresses possible risks, benefits, challenges, and socio-ecological shifts. In order to find compromise solutions, this approach should be based on an understanding of the positions of each stakeholder group involved in the project planning and affected by its implementation.

To understand these potential conflicts, a group of IIASA Risk and Resilience Program researchers, including myself, Jenan Irshaid, Love Ekenberg and Joanne Bayer, are conducting a series of six stakeholder workshops in Jordan. Each of the workshops targets different stakeholder groups such as local communities, NGOs, financial institutions, project developers, private companies, academia, young leaders, and national policymakers, including ministries of public works, of water and irrigation, energy and mineral resources, and municipal affairs. The goal of these workshops is to understand how different groups of stakeholders see risks and benefits of different electricity generation technologies, including renewables, fossil fuels, and nuclear, as well as views and visions of different stakeholders of Jordan in 2040 in terms of the social, environmental, and economic situation.

In our research we go beyond the existing discussion on social acceptance as a proxy of a Not-in-My-Back-Yard (NIMBY) attitude. NIMBY is often a misleading concept to understand local objections, because it is frequently understood as some kind of “social gap” between the need of policy intervention, settled at the national level, and the hostility towards its deployment at the local level. The NIMBY concept often includes skepticism of different stakeholder groups towards positions of the others. Also the term “acceptance” towards technology or infrastructure innovation often means a passive position towards something that cannot be changed. In contrary, willingness to use technology or to participate financially means a more active position.

In recent research, we discuss the usefulness of a model that we call “decide-announce-defend” (DAD), and try to understand how integration of various views and risk perceptions can lead to enhanced legitimacy of decision-making processes and trust. To understand the trade-offs between benefits of national energy goals and conflict sensitivity, we evaluated each electricity generation technology that could be relevant for Jordan against a set of criteria, including domestic value chain integration, use of domestic resources, technology and knowledge transfer, global warming potential, electricity system costs, job creation processes, pressure on land and water resources as well as safety, air pollution and non-emission waste.

Participants in the workshop. ©Nadejda Komendantova | IIASA

The workshops are organized in collaboration with the University of Jordan as part of the Middle East North African Sustainable Electricity Trajectories (MENA Select) project, which is supported by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and involves following partners: Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC), University of Flensburg, Germanwatch, Wuppertal Institute and IIASA as well as a number of partners in the MENA region, such as MENARES, University of Jordan, and DUN.

Further information

Ekenberg, L., Hansson, K., Danielson, M., Cars, G., (2017) Deliberation, Representation and Equity: Research Approaches, Tools and Algorithms for Participatory Processes, Open Book Publishers, 2017.

Komendantova, N., and Battaglini, A., (2016). Beyond Decide-Announce-Defend (DAD) and Not-in-My-Backyard (NIMBY) models? Addressing the social and public acceptance of electric transmission lines in Germany. Energy Research and Social Science, 22. Pp.224-231.

Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Scolobig, A., Ferlisi, S., Cascini, L. and Thompson, M. (2016) Expert engagement in participatory processes: translating stakeholder discourses into policy options. Natural Hazards, 81 (S1). pp. 69-88. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/view/iiasa/182.html

Yazdanpanah, M., Komendantova, N., Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Shirazi, Z., (2015). “Green or In Between? Examining Young Adults’ Perceptions of Renewable Energy in Iran”. Energy Research and Social Science 8 (2015), 78-85

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.