May 17, 2019 | Alumni, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

By Tobias Sieg, IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program alumnus

IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program alumnus Tobias Sieg explains how risk assessments considering uncertainties can substantially contribute to better risk management and consequently to the prevention of economic impacts.

© Topdeq | Dreamstime.com

According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Landscape 2018, extreme weather events and natural disasters are ranked among the top three global risks. For many regions, hydro-meteorological risks – in other words, weather or water related events like cyclones or floods that pose a threat to populations or the environment – constitute the biggest threat. This calls for a comprehensive scientific risk assessment with a particular focus on large associated uncertainties.

Assessing the risk of hydro-meteorological hazards without considering these uncertainties, is like entering a pitch-dark labyrinth. You have no idea where you are and where you will end up. If you enter with a flashlight, you might still not immediately know exactly where you will end up, but at least you can assess your possibilities for finding a way out.

We should all care to see those possibilities and to identify uncertainties, since the consequences of hydro-meteorological hazards can have severe impacts on socioeconomic systems, and global- and climate change could favor the occurrence of floods. An increase in extreme weather events, such as heavy precipitation can be expected along with an increasingly warmer climate. In combination with uncontrolled socioeconomic development, these extreme weather events could potentially trigger more intense hazardous flood events in the future. Appropriate management of their consequences is therefore required, starting from today, while pro-actively thinking about the future. To that end, risk management policy and practice need reliable estimates of direct and indirect economic impacts.

The reliability of existing estimates is usually quite low and, what is maybe even worse, they are not communicated properly. This may signal a false sense of certainty regarding the prediction of future climate-related risks.

In two recent studies, my co-authors and I developed and applied a novel method, which specifically focuses on the communication of the reliability of economic impact estimates and the associated uncertainties. The proposed representation of uncertainties enables us to shed some light on the possibilities of how a specific event can affect economic systems. As a Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant with the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program, I applied the method together with my supervisors Thomas Schinko and Reinhard Mechler, to estimate the overall economic impacts of a major flood event in Germany in 2013.

The estimated overall economic impacts comprise both direct and indirect impacts. Direct impacts are usually caused by physical contact of the floodwater with buildings, while indirect impacts can also occur in regions that are not directly affected by a flood. For example, obstructions of the infrastructure can lead to delayed deliveries, in turn leading to negative impacts for the production of goods outside the flooded areas. The crucial novelty of this method is the integrated assessment of direct and indirect economic impacts. In particular, by considering how the uncertainties associated with the estimation of direct economic impacts propagate further into the estimates of indirect economic impacts.

Being able to reproduce what has happened in the past is essential to making credible predictions about what could potentially happen in the future. A comparison of reported direct economic impacts and model-based estimates reveals that the estimation technique already works quite reliably. The good news is that anyone can help to increase the predictive reliability even further. The method uses the crowdsourced OpenStreetMap dataset to identify affected buildings. The more detailed the given information about a building is, the more reliable the impact estimations can get.

Our study reveals that the potential of short-term indirect economic impacts (without considering recovery) are quite high. In fact, our results show that the indirect impacts can be as high as the direct economic impacts. Yet, this varies a lot for different economic sectors. The manufacturing sector, for instance, is much more affected by indirect economic impacts, since it is heavily dependent on well-functioning supply chains. This information can be used in emergency risk management where decisions have to be made about giving immediate help to companies of a specific sector to reduce high long-term indirect economic impacts.

We are now looking at different possibilities of how flood events could affect the economic system. Having a range of possibilities of the relation between these impacts makes them transferable between different regions with similar economic systems. Our results are therefore also relevant more broadly beyond the German case. This representation of uncertainties can help to get to a more credible and consistent risk assessment across all spatial scales. Thus, the method is able to potentially facilitate the fulfillment of some of the calls of the UN Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction.

Detailed risk assessments considering uncertainties can substantially contribute to better risk management and consequently to the prevention of economic impacts – direct and indirect, both now and in the future.

References:

[1] Sieg T, Schinko T, Vogel K, Mechler R, Merz B & Kreibich H (2019). Integrated assessment of short-term direct and indirect economic flood impacts including uncertainty quantification. PLoS ONE 14(4): e0212932. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15833]

[2] Sieg T, Vogel K, Merz B & Kreibich H (2019). Seamless estimation of hydro-meteorological risk across spatial scales. Earth’s Future. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EF001122

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 3, 2019 | Data and Methods, Risk and resilience, Women in Science

By Junko Mochizuki, researcher with the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program

IIASA researcher Junko Mochizuki writes about her recent research in which she and other IIASA colleagues developed an indicator to help identify vulnerable countries that should be prioritized for human development and disaster risk reduction interventions.

© Yong Hian Lim | Dreamstime.com

Working as part of an interdisciplinary team at IIASA, it is not uncommon for researchers to uncover disciplinary blind spots that would otherwise have gone unnoticed. This usually leads to a conversation that goes something like, “If only we could learn from the other disciplines more often, we can create more effective theories, methods, and approaches.”

My recently published paper with Asjad Naqvi from the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program titled Reflecting Risk in Development Indicators was the fruit of such an exchange. In one afternoon, our coffee conversation hypothesized various reasons as to why the disaster risk discipline continued to create one risk indicator after another while the development community remained silent on this disciplinary advancement and did not seem to be incorporating these indicators into ongoing research in their own field.

Global ambitions such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction call for disaster mainstreaming, in other words, that disaster risk be assessed and managed in combination with any development planning efforts. For various reasons, we however continue to measure development and disasters separately. We know that globally the poor are more exposed to risk and that disasters hurt development, but there was not a single effective measure that captured this interlinkage in an easy-to-grasp manner. Our aim was therefore to demonstrate how this could be done using the information on disasters and development that we already have at our disposal.

The Human Development Indicator (HDI) is a summary measure of average attainment in key dimensions of human development – education, life expectancy, and per capita income indicators – that are used to rank countries into four tiers of human development. Using the HDI as an example, Asjad and myself compiled global datasets on human development, disaster risk, and public expenditure, and developed a method to discount the HDI indicator for 131 countries globally – just as others have done to adjust for income– and gender-inequality. Discounting the HDI indicator for education, for instance, involves multiplying it by the annual economic value of the average loss in terms of education facilities, divided by the annual public expenditure on education. We did this for each dimension of the HDI.

Conceptually, the indicator development was an intriguing exercise as we and our reviewers asked interesting questions. These included questions about the non-linearity of disaster impact, especially in the health sector, such as how multiple critical lifeline failures may lead to high death tolls in the days, weeks, and even months following an initial disaster event. Other issues we examined were around possibilities for the so-called build-back-better approach, which offers an opportunity to create better societal outcomes following a disaster.

Our formulation of the proposed penalty function hardly captures these complexities, but it nevertheless provides a starting point to debate these possibilities, not just among disaster researchers, but also among others working in the development field.

For those familiar with the global analysis of disaster risk, the results of our analysis may not be surprising: disasters, unlike other development issues (such as income- and gender inequalities for which HDI have been reformulated), have a small group of countries that stand out in terms of their relative burdens. These are small island states such as Belize, Fiji, and Vanuatu, as well as highly exposed low and lower-middle income countries like Honduras, Madagascar, and the Philippines, which were identified as hotspots in terms of risk-adjustments to HDI. Simply put, this means that these countries will have to divert public and private funds to pay for response and recovery efforts in the event of disasters, where these expenses are sizeable relative to the resources they have in advancing the three dimensions of the HDI indicator. Despite their high relative risk, the latter countries also receive less external support measured in terms of per capita aid-flow.

Our study shows that global efforts to promote disaster risk reduction like the Sendai Framework should be aware of this heterogeneity and that more attention in the form of policy support and resource allocation may be needed to support groups of outliers. Finally, although the cost of most disasters that occur globally are small relative to the size of most countries’ national economies, further sub-national analysis will help identify highly vulnerable areas within countries that should be prioritized for development and disaster risk reduction interventions.

Reference:

Mochizuki J & Naqvi A (2019). Reflecting Disaster Risk in Development Indicators. Sustainability 11 (4): e996 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15757]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 10, 2018 | Demography, Education, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

© SasinTipchai | Shutterstock

By Sandra Ortellado, 2018 Science Communication Fellow

Science fiction depicts the future with a combination of fascination and fear. While artificial intelligence (AI) could take us beyond the limits of human error, dystopic scenes of world domination reveal our greatest fear: that humans are no match for machines, especially in the job market. But in the so-called fourth industrial revolution, often known as Industry 4.0, the line between future and fiction is a thread of reality.

Over the next 13 years, impending automation could force as many as 70 million workers in the US to find another way to make money. The role of technology is not only growing but also demanding a completely new way of thinking about the work we do and our impact on society because of it.

Rather than focusing on which jobs will disappear because of technological disruption, we could be identifying the most resilient tasks within jobs, says J. Luke Irwin, 2018 YSSP participant. His research in the IIASA World Population program uses a role- and task-based analysis to investigate professions that will be most resilient to technological disruption, with the hope of guiding workforce development policy and training programs.

“We are getting better and better at programming algorithms for machines to do things that we thought were really only in the realm of humans,” says Irwin. “The amount of disruption that’s going to happen to the work industry in the next ten years is really going to impact everyone.”

However, the fear and instability created by the potential disruption elicit chaos, and the response is hard to organize into constructive action. While the resources remain untapped, creativity and imagination are wasted on speculation instead of preparation.

“I couldn’t stand that there’s all this great evidence-based work out there about how we can improve people’s lives and no one is using it,” said Irwin, “I’m trying to align a lot of research and put it in a place where you can compare it and make it more useful and more transferable between the people who would be talking about this: educators, policymakers, employers, and anybody in the workforce.”

Using a German dataset with vocational training as well as time and task information, Irwin will break down jobs into the specific cognitive and physical skills involved and rank the durability of each skill.

Based on the identified jobs and skills, Irwin will go on to draw connections between labor-force capabilities and education policies. His goal is to scale the findings of the most resilient skills to the German labor system so that policymakers and academic institutions can retrain currently displaced workforces and reimagine the future of human work.

After all, while about half the duties workers currently handle could be automated, Mckinsey Global Institute suggests that less than 5% of occupations could be entirely taken over by computers. The future of predictable, repetitive, and purely quantitative work may be threatened, but automation could also open the door for occupations we can’t even imagine yet.

“I think people are amazing and that they have a lot more potential than we are currently capable of fulfilling,” says Irwin.

The World Economic Forum estimates that 65% of children today will end up in careers that don’t even exist yet. For now, an increasingly self-employed millennial generation works insecure, unprotected jobs. The new gig economy, characterized by temporary contracted positions, offers independence but also instability in the labor market.

Without stable work, people lose a sense of security, and that can be dangerous for a policy system that isn’t built to handle uncertainty.

The last industrial revolution caused two or three generations of people to be thrown into poverty and lose everything they had because it was all tied into their job, recalls Irwin.

“Everything gets bad when things are uncertain,” says Irwin, “And this is a very uncertain time. We need to have a better idea of what’s coming so we can actually make some change.”

Irwin, who earned his Master’s in Public Health in 2014, wants his work to have a preventative focus, trying to find those things that not enough people are talking about, but have the potential to make a huge impact on public well-being.

“Especially in the United States, where I live, we’re so tied up with our jobs—it seems like it’s over half our identity,” says Irwin, “We live to work in America.”

In a place like the US, where a job is not only a source of income, but also an identity and a health factor, Irwin’s research offers hope that technological disruption can foster opportunity instead of chaos.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 7, 2018 | Data and Methods, Risk and resilience, Women in Science, Young Scientists

by Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Having just finished tenth grade, Lillian Petersen from New Mexico, USA is currently spending the summer at IIASA, working with researchers from both the Ecosystems Services and Management (ESM), and Risk and Resilience (RISK) programs on developing risk models for all African countries.

At a talk Petersen gave at the Los Alamos Nature Center/Pajarito Environmental Education Center, her method for predicting food shortages in Africa from satellite images caught the attention of Molly Jahn from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Jahn, who is collaborating with the ESM and RISK programs at IIASA, was so impressed with Petersen’s work that she added her to her research group and connected her to IIASA researchers for a joint project.

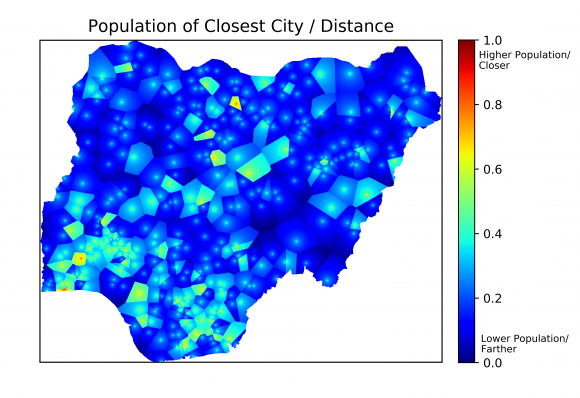

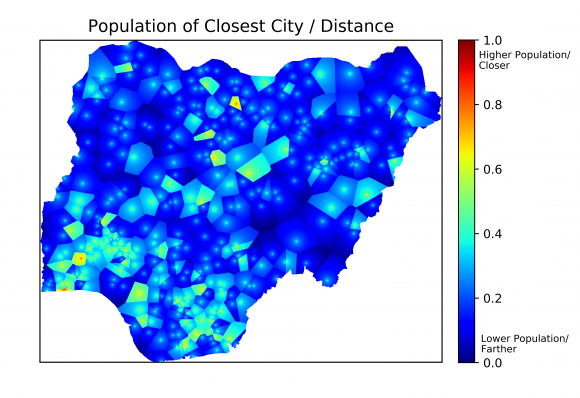

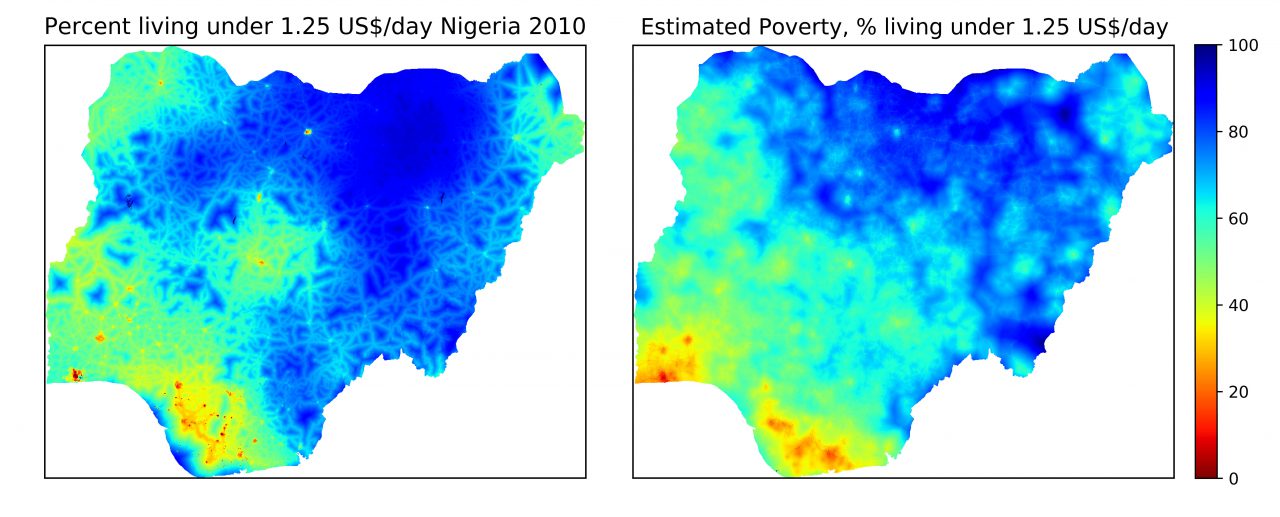

One of the indicators used to estimate poverty in Nigeria. © Lillian Petersen | IIASA

Knowing which areas are at risk for disasters like conflict, disease outbreak, or famine is often an important first step for preventing their occurrence. In developed countries, there is already a lot of work being done to estimate these risks. In developing countries, however, a lack of data often hinders risk modeling, even though these countries are often most at risk for disasters.

Many humanitarian crises, like famine, are closely connected to poverty. However, high resolution poverty estimates are only available for a few African countries. This is why Petersen and her colleagues are developing methods to obtain those poverty estimates for all of Africa using freely available data, like maps showing major roads and cities, as well as high-resolution satellite images. Information about poverty in a certain region can be extracted from this data by considering several indicators. For example, areas that are close to major roads or cities, or those that have a large amount of lighting at night, meaning that electricity is available, are usually less poor than those without these features. The researchers are also analyzing the trading potential with neighboring countries, the land cover type, and distance to major shipping routes, such as waterways.

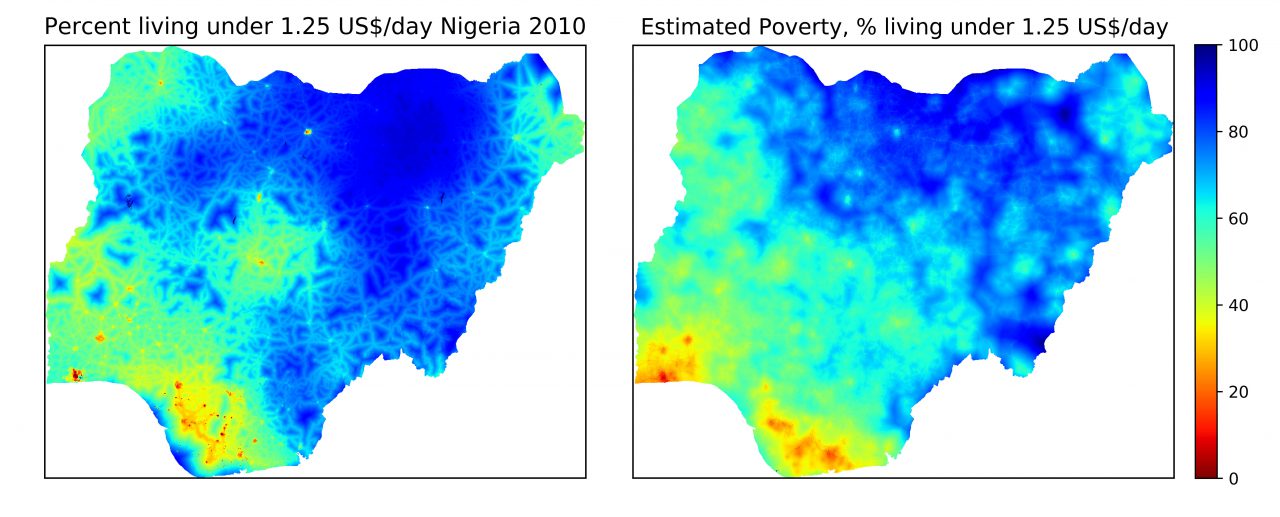

As no single one of these indicators can perfectly predict poverty, the scientists combine them. They “train” their model using the countries for which poverty data exists: A comparison of the model’s output and the real data helps to reveal which combination of indicators gives a reliable estimate of poverty. Following this, they plan to apply that knowledge in order to accurately predict poverty with high spatial resolution over the entire African continent.

Poverty data for Nigeria in 2010 (left) and poverty estimates based on five different indicators (right). © Lillian Petersen | IIASA

Once these estimates exist, Petersen and her colleagues will apply risk models to find out which areas are particularly vulnerable to disease outbreaks, famine, and conflicts. “I hope that this research will inform policymakers about which populations are most at risk for humanitarian crises, so that they can target these populations systematically in aid programs,” says Petersen, adding that preventing a disaster is generally cheaper than dealing with its aftermath.

The skills Petersen is using for her research are largely self-taught. After learning computer programming with the help of a book when she was in fifth grade, Petersen conducted her first research project on the effect of El Nino on the winter weather in the US when she was in seventh grade. “It was a small project, but I was pretty excited to obtain scientific results from raw data,” she says. After this first success she has been building up her skills every year, by competing at science fairs across the US with her research projects.

Her internship at IIASA gives Petersen access to the resources she needs to take her research to the next level. “Getting feedback from some of the top scientists in the field here at IIASA is definitely improving my work,’’ she says. Petersen is hoping to publish a paper about her project next year, and wants to major in applied mathematics after she finishes high school.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 14, 2017 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience

By Thomas Schinko, research scholar in the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program.

The hurricanes that swept across the Atlantic in the last few months had terrifying, and in Irma’s case record-breaking, power. They flattened homes and destroyed electricity grids, flooded schools and even threatened the integrity of whole nations. Could some of that immense power provide the impetus we need to switch from talking about climate-related risks and damages to doing something about them proactively?

On top of the hurricanes, in just the last two months the world has seen major flooding in Asia, and scorching heatwaves in southern Europe. While climate-related risks are shaped by many factors, the science shows that climate change is loading the dice, making certain extreme events more likely, and providing more favorable conditions for their formation.

Many are pessimistic about our abilities or inclination to heed the wake-up call. They worry that current political divisions and governance structures will leave us dead in the water.

I have hope. I have been working with colleagues on a way forward on managing climate-related risks that defuses the political nature of the debate and helps forging a stakeholder compromise. At all governance levels and all across the globe, disaster risk management has a long and proven track record for dealing with climate-related and other geophysical extremes, such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. This established and politically uncontroversial setting is the point of departure for the concept of ‘climate risk management’. This new concept aims to deal with disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation at the same time, providing a way to circumvent the political hurdles and strengthen global ambitions to tackle climate-related risks.

Aligning climate change adaptation and disaster risk management

In the medium to long term, climate change and adaptation must be incorporated into all kinds and levels of decision and policy making. We can achieve this by increasing understanding of the risks of climate change, and adjusting policy and practice over time according to the latest knowledge and expertise. The importance of climate change is already being recognized in diverse decisions and policies. Just recently, for example, Hong Kong Airport announced that the project to build a third runway incorporated sea level rise projections by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and based on that will include the construction of a sea wall, standing at least 21 feet above the waterline.

Broad stakeholder participation

Putting climate risk management into practice requires balancing the perceptions of climate-related risks of all involved. This calls for a process that involves the participation of those in politics, public administration, civil society, private sector and research.

Putting climate risk management into practice requires balancing the perceptions of climate-related risks of all involved. © Aleksandr Simonov

This may sound excessively time consuming, or even impossible, but it’s not. I know that because I am involved in helping to apply climate risk management in the context of flood risk in Austria. We are only just embarking on the process, and it is lengthy, involving extensive collaboration with relevant ministries, departments, and the private sector—such as insurance companies—but ultimately it can help to co-create a strong policy for the future.

Despite considerable uncertainties in establishing a strong causal link to anthropogenic climate change as risk driver, by employing climate-relevant science to decision making on existing short-term risks we were able to kick-start a process to act on flood risk in the country. This includes critically reflecting on existing policy tools, such as the Austrian disaster fund, and injecting aspects of climate-related risk into long-term budget planning processes.

New solutions to tackle increasing levels of climate risk

As risks increase, however, moving beyond incremental adjustments of existing policy tools is imperative, and totally new solutions will have to be found. Tackling erosive and existential climate-related risks, which lead to the complete loss of people’s and communities’ livelihoods, would require truly transformational action. Such risks are currently discussed under the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts, which was established in 2013 at the 19th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

For the case of increasingly intolerable flood risk this could mean that in the future raising dikes might not suffice and governments may need to start supporting alternative livelihoods (for example, switching from farming to services sectors); providing climate-resilient social protection schemes; or assisting with voluntary migration. This requires climate risk management to be a learning process itself; flexible towards adjusting to any ecological, societal or political transformations.

Towards transformational climate risk management

To tackle the substantial challenges imposed by increasing climate-related risks, truly transformational thinking is needed. By accounting for underlying socioeconomic and climate-related drivers of risk, as well as for different stakeholder perceptions, climate risk management allows compromises to be achieved that translate into concrete but adaptable action.

Assam Integrated Flood and Riverbank Erosion Risk Management Investment Program in India. © Asian Development Bank

Transformational thinking requires reframing of the overall problem over time. Reframing, in this context, refers to a change in the collective view on climate-related risks and how to tackle those. Taking again flood risk as a case in point, comprehensive flood risk management plans that are based on broad stakeholder participation processes and that allow for adaptive updates over time could be created. In the short term, re-evaluating existing measures may lead to an incremental adjustment of existing flood risk management efforts. The transformative notion comes in over time via proactively discussing trends in climate-related risks, which might eventually lead to the design of new policies and implementation measures, potentially also requiring alternative governance structures.

What is needed next is to provide space and resources for putting climate risk management processes, such as outlined here, into action. It would be a wise decision to seize the historic chance provided by the current alertness to the issue and start taking proactive action on today’s and future losses and damages due to climate-related risks.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 21, 2017 | Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

Ziyun Zhu is a PhD student at Peking University Centre for Nature and Society, and research assistant at the Shanshui Conservation Center, China. He is currently attending the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program and talks to Science Communication Fellow 2017 Caroline Njoki about his current research on wildlife damage insurance schemes as a strategy to manage human-wildlife conflict.

What is your research about and what do you aim to achieve during your time at IIASA?

Wildlife insurance schemes compensate local people in case wild animals attack their livestock, or damage their crops or property, if a wolf kills a sheep, for instance. These schemes are a relatively new tool for mitigation of human-wildlife conflicts and there isn’t sufficient information on when this is the best option and where other tools may apply. My research is to clarify the different scenarios where insurance can work, based on existing insurance projects and other mitigation measures from other parts of the world. This will help improve insurance schemes for other areas.

Effective ways of managing human-wildlife conflicts are required to ensure survival of species such as the Snow leopard © Peter Wey | Shutterstock

Tell us more about the community wildlife insurance scheme?

The Tibetan Plateau contains unique wildlife including snow leopards, wolves, and Tibetan brown bears. The people living on the plateau keep yaks and sheep, and co-exist with wildlife. However, there are cases when interactions between people and carnivores result in conflict and disruption of people’s livelihoods, and may lead to retaliatory killing of wildlife.

A voluntary Community Wildlife Insurance Scheme, started by the non-governmental organization Shanshui Conservation Center in 2008, runs on premiums contributed by the members. This makes the scheme more self-sufficient than traditional government-funded compensation, which often lacks funding. The premium depends on type of animal (sheep or yak) and number they keep and also covers damage to their homes by bears. The validation process is also streamlined to ensure claims are paid out quickly.

Members meet annually to elect leaders to manage the pilot scheme, evaluate performance, and review the premiums in line with market trends. In consultation with the members, leaders determine the premium based on the market but also make them affordable. The members are also encouraged to put in place other mitigation measures.

A traditional tent made from yak wool. Tibetan people possess rich indigenous ecological knowledge © Lingyun Xiao

Herders have negative attitudes towards brown bears, yet bears attacking livestock is rare compared to other predators. Why is that?

The availability of pasture on the plateau is seasonal. Herders and their families lived in yak-wool tents until a government initiative to support them to build winter houses in the mid-1990s. When herders move from their winter to summer grounds, bears sometimes break into their mud brick houses, consume stored food, and damage property. The herders must then pay for repairs and replacements, hence the strong negative attitude towards bears. Working closely with local communities to raise awareness and develop suitable mitigation measures is key to promoting co-existence with wildlife.

What are your highlights from working on the Tibetan Plateau?

Ziyun Zhu treasures sighting a snow leopard in the wild and his work in the Tibetan Plateau offers him an opportunity to connect with nature away from city life © Caroline Njoki | IIASA

During fieldwork to determine presence of the snow leopards on the plateau, which are very shy and elusive, one dashed from above the cave and disappeared in the rocks while we were placing camera traps. This was definitely a highlight for me. I also enjoy working with the people, who possess a rich indigenous ecological knowledge. My PhD aims to document this information and how it may contribute to conservation of Tibetan’s biodiversity. For instance, the collection of plants and hunting of animals are not allowed in certain areas designated as sacred or of high cultural importance. There is little human interference, leaving much of the area pristine.

This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Reference

Juan Li, Hang Yin, Dajun Wang & Ziyun Zhi (2013). Human-snow leopard conflicts in the Sanjiangyuan Region of the Tibetan Plateau. Biological Conservation 166: 118-123.

You must be logged in to post a comment.