Dec 16, 2021 | Alumni, Demography, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Fanni Daniella Szakal, 2021 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Can we lift people out of energy poverty while simultaneously reducing carbon dioxide emissions? 2021 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant Camille Belmin tried to tackle this seemingly contradictory issue by including fertility in the equation and estimating the conditions where an increase in energy access would reduce demand through decreasing population sizes.

© Photopassion77 | Dreamstime.com

About every third person in the world today doesn’t have access to clean cooking fuels and 1 in 10 are without electricity, predominantly in the Global South. Increasing energy access will not only improve the quality of life for many, but it will also propel us towards achieving some of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) such as SDG3, Good Health and Wellbeing, and SDG7, Access to Clean and Affordable Energy.

The downside of increasing energy access is the surge in carbon dioxide emissions that will likely follow. Although populations with low energy access emit only a small share of global carbon emissions compared to countries in the Global North, an increase in energy provisioning would still put more pressure on the climate crisis. But, what if we could increase energy access and decrease emissions at the same time while tackling a few more SDGs in the process, such as SDG5, Gender Equality and SDG13, Climate Action?

Camille Belmin, a participant in the 2021 YSSP aimed to do just that. As a PhD Student at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and at the Humboldt University of Berlin, Belmin focuses on the relationship between energy access and women’s fertility. In a previous study covering 43 countries around the globe, she found evidence that higher access to electricity and modern cooking fuels was associated with women having fewer children.

“With more access to energy, instead of, for example, picking up firewood for many hours a day, women are able to spend more time on education and employment. Energy access also lowers the need for child labor and reduces child mortality through reduction of indoor air pollution and improved healthcare. This often leads to women becoming more empowered and gives them agency over their reproductive choices, leading to a fertility decline,” says Belmin.

In her YSSP project, Belmin took the energy-fertility relationship a step further: she wanted to explore if an initial boost in energy access could lead to a decline in energy demand in the long term through reduced population sizes, both increasing the quality of life and reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

“I hope that by showing that universal access to energy can also have benefits for sustainability, I can encourage investments in modern energy access in countries where basic services are lacking,” she notes.

To find out under which conditions increasing energy access will lead to a decrease in energy demand, Belmin used a microsimulation model of population projection. Under different energy access scenarios, the model follows each individual in a hypothetical population through life events, such as birth, death, and gaining access to education and electricity, while calculating their total energy consumption. She hoped to find a scenario with net savings in energy demand, in other words, a scenario where the more you give, the more you get.

Setting up the model was a new challenge for Belmin ̶ while many scientific fields have been using microsimulation for a long time, applying it to population modeling based on energy access is a novelty. The potential benefits and positive implications of the work were however well worth the difficulty.

The study focused on population simulations in Zambia, where Belmin collaborates with an NGO that aims to finance education for girls through carbon credits, building on the idea that education will lead to lower population sizes and decreased emissions in the future.

“Because of patriarchal structures, women are often bound to household chores, making the lack of energy a huge burden,” says Belmin. “This research is very important to me as a woman, or just as a human, as it seems that providing modern energy services might be a way for women to have more choice and freedom in their lives.”

Further information:

Belmin, C. (2021). Introducing the energy-fertility nexus in population projections: can universal access to modern energy lead to energy savings? IIASA YSSP Report. Laxenburg, Austria: IIASA [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17688]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 26, 2021 | Demography, Environment, Finland, IIASA Network, Poverty & Equity

By Venla Niva, DSc researcher with the Water and Development Research Group, School of Engineering, Aalto University, Finland

Venla Niva shares insights from a recent article exploring the interplay of environmental and social factors behind human migration. The project was carried out in collaboration with Raya Muttarak from the IIASA Population and Just Societies Program.

© Irina Nazarova | Dreamstime.com

Environmental migration has gained increasing attention in the past years, with recent climate reports and policy documents highlighting an increase in environmental refugees and migrants as one of the potential effects of the warming globe. Policymaking is dominated by a narrative that portrays environmental migration as a security threat to the “Global North”. Meanwhile, researchers around the world have put enormous efforts into understanding environmental migration and what is driving it. Yet, the causes and effects of environmental migration remain under debate.

In our latest paper, we extend the understanding of environmental migration by looking into how environmental and societal factors interacted in places of excess out- or in-migration between 1990 and 2000. We found that understanding these interactions is key for understanding migration drivers. Ultimately, migration is based on human decision-making, and in our view “simply cannot and should not be studied without the inclusion of the societal dimension: human capacity and agency.” Our findings were both expected and, to a certain degree, surprising.

Our results show that the majority of global migration takes place in areas with rather similar profiles. It is known that migration mostly occurs over short distances, and that internal migration – in other words, people moving around in their own country – outplays international migration – people moving between countries – by significant numbers globally. This, however, shows that the characteristics of these areas are alike too. High environmental stress coupled with low-to-moderate human capacity characterized these areas at both ends of migration. Such characteristics portray a combination of variables with a high degree of drought and water risks, natural hazards, and food insecurity, but low levels of income, education, health, and governance.

We found that income was the best variable to explain the variation of net-negative and net-positive migration in around half of the countries, globally, confirming that income is a good predictor of migration. This is interesting in two ways. According to traditional migration theories, income disparity between regions is seen as the primary driver for migration. Yet, income only dominated the other variables in half of the countries we examined. Education and health were especially important in areas with more out-migration than in-migration. Drought and water risks were important explaining factors in many countries, but were outranked by societal factors such as income, health, education, and governance in the majority of countries.

In light of our research, we would like to point out that it is unlikely that environmental factors alone would be responsible for migration. Instead, the role of human agency is vital. Investments in building human capacity have two-fold benefits: First, higher human capacity facilitates not only local adaptation to changes in the environment, but also adaptation at the destination in case of migrating. Second, protecting ecosystems and the environment helps to mitigate and adapt to climate and environmental change in areas with high environmental stress, which is again crucial for maintaining livelihoods and a good life at both ends of migration.

Environmental migration is often portrayed by the media as a catastrophic phenomenon. Our study confirms that migration drivers are a result of the interactions between socioeconomic and environmental factors and that human capacity plays a central role in both enabling the migration process and adaptation at the place of destination.

Further info:

Niva, V., Kallio, M., Muttarak, R., Taka, M., Varis, O., & Kummu, M. (2021). Global migration is driven by the complex interplay between environmental and social factors. Environmental Research Letters DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac2e86. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17507]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 18, 2021 | Climate, Climate Change, Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Marina Andrijevic, researcher in the IIASA Energy, Climate, and Environment Program

Marina Andrijevic tackles some inconvenient but fundamental issues around climate change adaptation.

© Lio2012 | Dreamstime.com

Anyone who followed climate-related headlines this summer would have noticed a more than usual amount of talk on climate change adaptation. As it goes with sudden epiphanies in aftermaths of humanitarian disasters in our Western realities, this time we’ve come to realize that we need to seriously think about doing some adaptation.

To be fair, the realization that adaptation is inevitable has for a long time been somewhat of a taboo in the “woke” climate policy and activist circles (the author of this blog is a millennial and would like to acknowledge that the reader’s idea of a long time in climate policy might be different). Admitting that there might be no other option but to adapt to whatever the locked-in effects of climate change are, is arguably defeatist and gives in to the notion that mitigation alone won’t cut it.

While this might be yet another depressing but accurate reflection of the reality under climate change, portraying adaptation and mitigation as different but equally urgent actions could set a dangerous trap if it produces ideas such as: if we adapt enough, perhaps our economies and energy systems won’t need to change so much.

Even if it would be enough (which it wouldn’t), adaptation will not necessarily just happen once we recognize it needs to be done, because the needs and abilities for it operate on different time horizons and geographical scales. Many parts of the world that need adaptation will not necessarily be able to take action, so we have to be very careful when we count on it as a solution to climate change.

This is where we must tackle some inconvenient but fundamental issues about adaptation. Climate change research, especially the areas positioned at the “interface” with policy, could play a crucial role here. In this role, it must be very prudent and avoid doing a disservice to decision makers, and even worse, to people affected by those decisions. In other words, the scientific assessments need to be careful when assuming for whom, where, and how adaptation can reasonably be expected.

We tried to illustrate why this matters in our recent paper that looks at the capacity of populations to adapt to heat stress. We used air-conditioning as a popular, albeit not (yet) climate-friendly adaptation option. My coauthors and I understand that air conditioning could well be maladaptation, meaning that it causes more harm than good in the long-run. Adaptation practices, however, it turns out, are quite difficult to measure, while installed air conditioners can literally be counted, which makes them handy for plugging into our statistical models. We contend with access to air conditioning currently being a good enough example of access to adaptation and promise to assess more options in the future.

Our paper shows how the capacities to protect against heat stress vary widely around the world. Like with many other unjust manifestations of climate change, people in the world’s hottest areas also have the least means to adapt. We found that countries with more income, more urban areas, and less income inequality, are also the ones where more people have access to air conditioning.

This does not come as the world’s biggest revelation, but it conveniently allows us to make informed guesses on how access to air conditioning might change in 2050 or 2100. This is possible because the research community has already engaged in a group effort to propose five different futures with regard to GDP, urbanization, and income distribution (in climate jargon: the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways or SSPs).

Coupling the potential rates of air conditioning with the people exposed to heat stress based on projections of climate models, lets us calculate the cooling gap – the difference between people exposed to heat stress and people who can protect themselves against it with the use of air conditioning.

Depending on whether we find ourselves in the best- or the worst-case scenario of socioeconomic development could mean anywhere between two billion and five billion people globally unable to protect themselves against heat stress with air conditioning in 2050. This range only grows with longer time horizons, with Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia being the areas of the world where these differences are the starkest.

We hope that our paper will motivate further investigations of potential gaps in adaptation that point to insufficient adaptive capacity and help to identify the areas and populations most at risk, as well as what additional work needs to be done in terms of socioeconomic improvements before we can reasonably expect adaptation to take place. Our findings on the importance of factors beyond just GDP, suggest that helping communities to build their adaptive capacity doesn’t mean only throwing money at them (although that would make for a decent start!), but international efforts must focus on issues such as eradicating inequalities, supporting smart urban development, strengthening institutions, and providing education.

So, let’s not take it for granted that we will all be able to adapt either now or in the future. Eliminating the causes of climate change must remain the number one policy objective that will help to reduce the need for adaptation in the first place. But number two could be helping communities that have no option but to cope with what’s already coming at them. Highlighting in our research what the implications of different adaptive capacities are for preservation of livelihoods, is a small step towards achieving this.

Reference:

Andrijevic, M., Byers, E., Mastrucci, A., Smits, J., & Fuss, S. (2021). Future cooling gap in shared socioeconomic pathways. Environmental Research Letters 16 (9) e094053. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17411]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 20, 2021 | COVID19, Poverty & Equity, Risk and resilience, Women in Science

By Benigna Boza-Kiss, Shonali Pachauri, and Caroline Zimm from the IIASA Transformative Institutional and Social Solutions Research Group

Benigna Boza-Kiss, Shonali Pachauri, and Caroline Zimm explain how COVID-19 has impacted the poor in cities and what can be done to increase the future resilience of vulnerable populations.

© Manoej Paateel | Dreamstime.com

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought a halt to life as we knew it. We have been restrained in our activities and freedoms, forced to stay indoors at home, to cancel travel plans, and to transfer meetings to an online space, where most of us have also celebrated birthdays and other important life events that should have been in person with our loved ones. These changes have impacted many aspects of our comfort, our social wellbeing, as well as our financial situations, but it has also brought existing inequalities and poverty into the spotlight.

The risks of the pandemic and restrictions following containment measures have been felt most acutely by the poor, the vulnerable, those in the informal sector, and those without savings and safety nets. The suffering of women in the health sector, school children in households without electricity and internet, workers in the informal sector that don’t have the option to telework, crowds living in slums – to name just a few examples of vulnerable groups – have become glaringly visible to all. These people have had to adapt to new rules and conditions when they were living on the edge even before the pandemic.

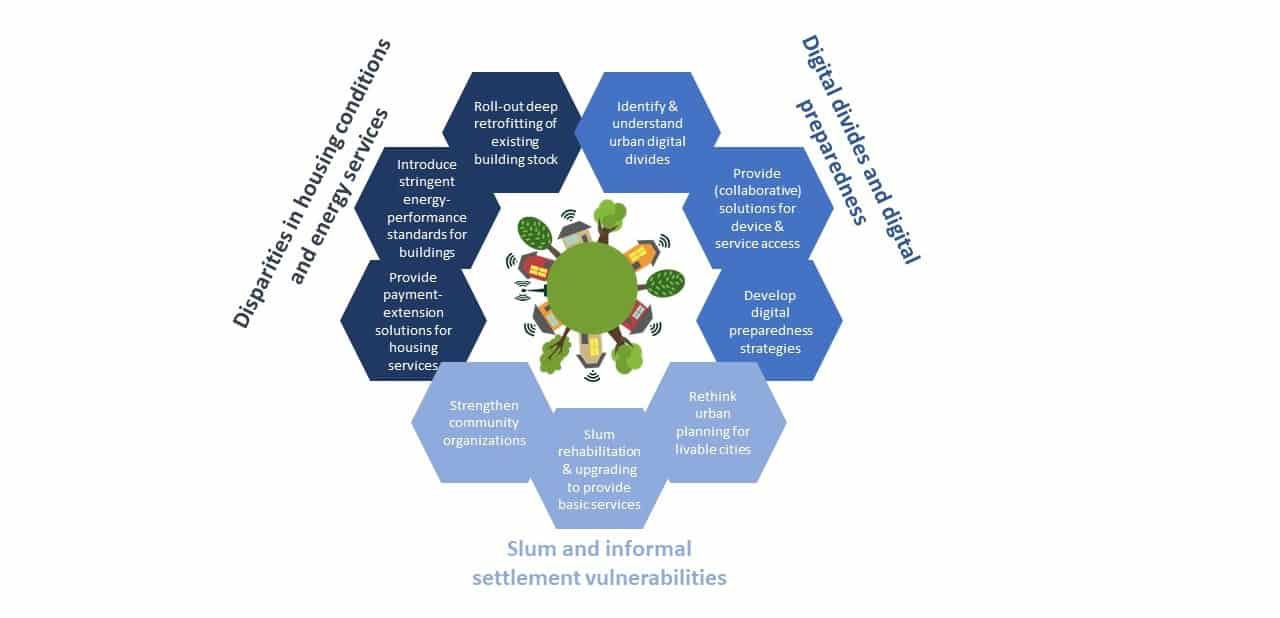

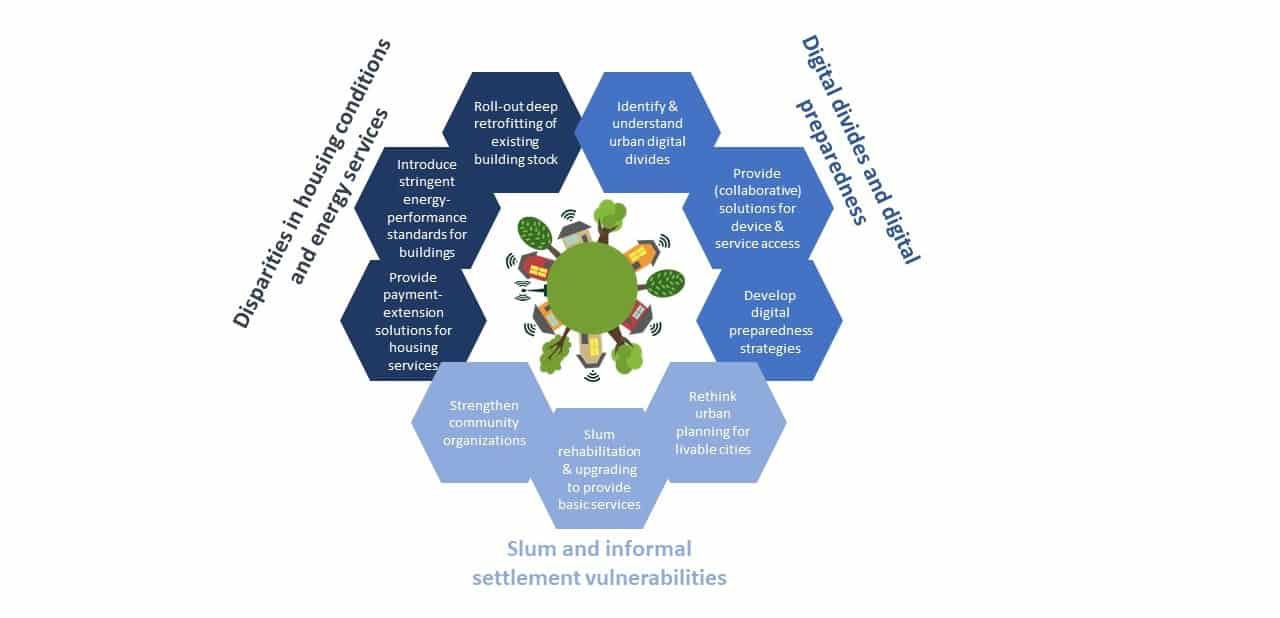

In a new perspective piece published in the journal Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, we explored how aspects related to access to shelter/housing, modern energy, and digital services in cities have influenced the poor and what can be done to increase the future resilience of vulnerable populations.

We described three ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic and related containment measures have exacerbated urban inequalities, and identified how subsequent recovery measures and policy responses could redress these.

First, lockdowns amplified urban energy poverty. Staying at home has meant increased energy use at home. For the poor, who already struggle with utility costs, and typically live in low energy quality buildings, these services have become even more unaffordable. These populations also shoulder a higher burden of poor health, for example, higher incidence of respiratory problems, with poor or inadequate ventilation and insulation increasing their risk of infection even more.

Second, preexisting digital divides have surfaced, even within well-connected cities. Multiple barriers limit digital inclusion: access to digital technologies due to high costs (for devices, internet access, and electricity connections), and unreliable services (again both for electricity and internet), as well as low digital literacy and support. This lack of adequate digital service access is contributing to these populations falling further behind during lockdowns as they miss out on education and income.

Third, slum dwellers in the world’s cities have been particularly hard hit, because of precarious and overcrowded housing conditions, lack of basic infrastructure and amenities, and a high concentration of the socioeconomically disadvantaged, resulting in even more negative consequences of lockdown measures. With many slum inhabitants working in the informal sector, many have been left either without jobs and income, or have been compelled to work in precarious and unsafe conditions to survive. The loss of income has also had knock-on effects, making payments of regular expenditures for rent, water, electricity, and other utility services difficult. Women within these settlements have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, as they are over represented in the informal economy, and more likely to be engaged in invisible work, such as home-based or domestic and care work.

Recovery measures need to ensure immediate relief, but also point towards long-term solutions that contribute to the redistribution of wealth and new urban development, while also increasing resilience to the current and future pandemics or other disasters. There are tested measures that should be reemphasized.

Urban green recovery plans that include large-scale home renovation programs could ensure warm, healthy homes, and affordable energy bills for all. In the shorter-term, alleviation of payment defaults on the rents and utility bills of the energy poor should continue. In parallel, urban digital preparedness, more equal access to the virtual delivery of essential services, and provision of opportunities for virtual working and education for all in the future, need attention.

COVID-19 can be a wake up call to increase efforts to close the digital divide and push for structural change. The crisis has increased the urgency to redesign and improve informal settlements and provide adequate and efficient services that address the diverse needs of poor urban residents. This requires partnerships between urban municipalities, planners, and stakeholders, as well as strengthening local communities for inclusive planning strategies. More immediately, it is necessary to provide direct support to slum and informal settlement populations in terms of income support, adequate nutrition, energy, water, and other basic infrastructure and services.

All in all, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a “test of societies, of governments, of communities, and of individuals”. Digital technologies, home renovation, and slum rehabilitation are the means, rather than the end to improve conditions for all, but if specifically targeted to the poor and most deprived, such measures can reduce inequalities and increase resilience.

All in all, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a “test of societies, of governments, of communities, and of individuals”. Digital technologies, home renovation, and slum rehabilitation are the means, rather than the end to improve conditions for all, but if specifically targeted to the poor and most deprived, such measures can reduce inequalities and increase resilience.

Reference:

Boza-Kiss, B., Pachauri, S., & Zimm, C. (2021). Deprivations and Inequities in Cities Viewed Through a Pandemic Lens. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 3 e645914. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17121]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 12, 2021 | Poverty & Equity, Risk and resilience, Sustainable Development

by Viktor Roezer | Swenja Surminski | Finn Laurien | Colin McQuistan | Reinhard Mechler | Anna Svensson

Disaster Risk Reduction investments bring a wide variety of benefits, including economic, ecological, and social, but in practice these multiple resilience dividends are often not included in investment appraisals or are not recognized by those making funding decisions. How do we change this?

Research led by the London School of Economics and Political Science with IIASA and Practical Action published in the Working Paper Multiple resilience dividends at the community level: A comparative study on disaster risk reduction interventions in different countries highlights the need for an integrated decision-making framework to overcome the challenges.

The negative effects of disasters on people and communities are varied and far reaching, and will only get worse as climate change make floods and other natural hazards more frequent, severe, and unpredictable. Disasters lead to loss of lives, assets, and livelihoods, they undermine or destroy development progress. Since 2000 climate related hazards have caused $2.2 trillion of losses and damages and have affected approximately 3.9 billion people globally.

With investments in disaster risk reduction (DRR), where community resilience is enhanced these negative impacts can be reduced and savings can be made. It’s more cost effective to invest in pre-event resilience than post-event response and recovery.

So why is disaster risk reduction so difficult to finance?

The problem with estimating the direct benefit of disaster risk reduction interventions is that you only see the benefits when an event which would otherwise have turned into a disaster occurs and is successfully mitigated.

This makes cost-benefit analysis and other decision-making methods difficult to carry out, and makes the costs of doing something more aligned to the probability of the event, rather than the lives and economic costs saved, thus changes to policy and practice are slow to materialize.

What are the multiple dividends of resilience?

The multiple dividends of resilience refer to positive socioeconomic outcomes generated by, and co-benefits of, an intervention beyond, and in addition to, risk reduction.

It’s an approach aimed at making DRR investments more attractive as the multiple dividends of an investment may help identify win-win-win situations (as well as trade-offs), even if no hazard event occurs. Co-benefits can be intended, or unintended.

As framed by the Triple Resilience Dividend concept these benefits can be divided into three categories:

1. The avoided losses and damages in case of a disaster

For example, how bio-dykes in Nepal prevent river bank erosion, which reduces the risk of flooding, and associated sand deposits that ruin the fertility of agricultural land.

2. The economic potential of a community that is unlocked through the intervention

This includes ecosystem-based adaptation solutions in Vietnam where mangrove plantations create new habitats for fish, leading to improved livelihood opportunities for those making their living from fishing.

3. Other development co-benefits

Transition to solar stoves in rural Afghanistan does not only protect natural capitals from degradation, but also empowers women and girls, reduces in-house smog pollution, and fosters technological innovations.

Rongali next to his community’s bio-dyke. Photo by Sanjib Chaudhary, Practical Action.

What are the challenges?

The triple resilience dividend approach is often linked to new and innovative solutions like ecosystem based adaptation, where the benefits can be wider, but when and how they will materialize is more uncertain than with traditional, hard infrastructure solutions.

Although many developing countries have policies that align DRR, climate change adaptation, and sustainable development, sadly, in practice, local decision makers assume that multiple resilience dividends will only accumulate over the long term. This often leads them to select traditional, hard infrastructure solutions that offer quick and more visible protection.

We need more success stories. Pilot interventions can be shared and shown to community members and decision makers to overcome their skepticism but this require better and more comprehensive evidence than we have today.

We also lack decision-making frameworks that can include and monitor multiple resilience dividends. Frameworks that support planners as they navigate the decision-making process, and help generate the evidence needed.

Community members in the Peruvian Andes working at a local tree nursery. Photo by Giorgio Madueño , Practical Action

How do we overcome these challenges?

The solution suggested in Multiple resilience dividends at the community level: A comparative study on disaster risk reduction interventions in different countries is an integrated decision-making framework that allows to systematically include, appraise, implement, and evaluate individual resilience dividends at each stage of the decision-making process.

Application and relevance matters.

As we suggest, instead of maximizing resilience dividends based on a specific, one dimensional, metric (e.g., monetary benefits) decision-making approaches need to identify those dividends that are most needed and demanded by the community and the solutions, novel or local in nature, best suited to generate these.

A structured approach in combination with participatory decision making allows for a tailored approach where community buy-in is achieved by prioritizing the resilience dividend(s) that matter most to them, while at the same time contributing to the evidence base for multiple resilience dividends.

This is urgently needed to highlight the fundamental challenges with the existing planning and decision-making system and therefore generate demand to deliver more effective solutions at scale.

Cleaning waste from river in Penjaringan Urban Village, Jakarta, Indonesia. Photo by Piva Bell, Mercy Corps.

Read the working paper this blog is based on here.

This blog post first appeared on the Flood Resilience Portal. Read the original post here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 5, 2021 | Climate Change, Poverty & Equity, Risk and resilience

By Julian Joseph, research assistant in the Water Security Research Group

Julian Joseph explains the concept of the triple dividend of disaster risk reduction investments based on the application of a novel economic model applied to a case study undertaken in Tanzania and Zambia.

What are the benefits of Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) investments such as dams and the introduction of drought-resistant crops in agriculture for an economy? They are threefold and called the “triple dividend” of DRR investments. The first dividend comprises the direct effects of DRR investments, which limit damage to houses, infrastructure, and other physical assets and prevent death and injury. The second dividend unlocks the economic potential of an economy because risk reduction drives people and businesses to invest more, as they expect less of what they invest in to be destroyed by disasters, while the third dividend is comprised of development co-benefits through other uses the investments provide.

© Gerrit Rautenbach | Dreamstime.com

Using a new macroeconomic model called DYNAMMICs, my colleagues and I have found that there is often a significant growth effect for the economy attached to investing in mitigation measures like dams and drought resistant crops, which is commonly underestimated in traditional models. One reason for this is the focus of other models on only the first, direct dividend. We specifically looked into the examples of Tanzania and Zambia, which show that governments and other stakeholders in developing countries can spur economic growth by investing in DRR measures, thus increasing future earnings and creating a safe environment for investments into other economic activities.

In Tanzania and Zambia, floods affect tens of thousands of people each year (on average 45,000 or .08% of the population in Tanzania and 20,000 or .11% of the population in Zambia). Droughts have more widespread consequences and already affect 11.8% of the population in Tanzania and 19% of Zambians who often lose all or parts of their harvest. This poses an imminent threat to food security in countries where substantial shares of the population rely on subsistence farming as their primary source of income. Given the effects of climate change, these numbers and their ramifications are bound to become ever more pressing issues. However, policymakers, institutions, enterprises, and individuals tend to underinvest in adaption measures.

A promising avenue for demonstrating the potential of DRR investments is offered by including all economic growth effects they invoke into policy analysis, thus showing that besides risk reduction and post-disaster mitigation of destruction, investing in DRR measures can help countries achieve many of their other development goals as well.

We tend to only think of the first dividend of DRR investments, the direct effects of which stop people from being immediately affected by disasters. In the case of Tanzania and Zambia, we examined, among others, the benefits of constructing additional dams. The direct benefits of dams lie in the safeguarding of livelihoods, infrastructure, housing, and agricultural production. These are seen as the first dividend, called the ex-post damage mitigation effect. There are however also additional co-benefits.

In both Tanzania and Zambia, large shares of the population are heavily dependent on agriculture, which makes the introduction of drought-resistant crop varieties such an additional benefit. These crop varieties do not only help farmers preserve their yields in times of disastrous droughts, but additionally support farmers by generating higher yields, even in the absence of disaster. This effect is boosted by the lowered risk for the loss of crops, which spurs investment into farming activities and inputs. Farmers who do not fear losing their entire harvest can, and generally will, invest more into the production of this crop – an example of the second type of dividend, the ex-ante risk reduction effect. This type of economically beneficial effect materializes regardless of the onset of disaster.

The same is true for the third type of dividend, the co-benefit production expansion effect, which is especially relevant for the advantages of dams. The power generation capability of dams, leads to much larger economic gains than the two other dividends combined. In countries such as those at hand with frequent power cuts and comparably low levels of electrification, especially in rural areas, the additional electricity generated can lead to particularly pronounced positive effects by supplying economic actors with access to power. In other scenarios, the provision of ecosystem services is also an important effect falling into this category.

The results we obtained using the DYNAMMICs model are promising: Constructing only two additional dams leads to a 0.3% increase of GDP growth in Tanzania for the next 30 years (0.2% in Zambia) with results largely (97%) driven by the co-benefit production expansion effect. Similarly, the introduction of drought resistant crops and exposure management (i.e., land use restrictions) significantly boost economic growth perspectives. Finally, introducing insurance is a driver for a reduction in the variance of GDP growth, which helps to reduce uncertainty for everyone in the economy. Modeling in such a fashion is therefore an important means of weighing policy options for DRR against each other and for determining optimal levels of investment.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.