Sep 23, 2019 | Ecosystems, Environment, Sustainable Development

By Frank Sperling, Senior Project Manager (FABLE) in the IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Food and land use systems play a critical role in managing climate risks and bringing the world onto a sustainable development trajectory.

The UN Secretary General’s Climate Action Summit in New York on 23 September seeks to catalyze further momentum for climate change mitigation and adaptation. The transformation of the food and land use system will play a critical role in managing climate risks and bringing the world onto a sustainable development trajectory.

Today’s food and land use systems are confronted with a great variety of challenges. This includes delivering on universal food security and better diets by 2030. Over the last decades, great strides have been made towards achieving universal food security, but this progress recently grinded to a halt. The number of people suffering from chronic hunger has been rising again from below 800 million in 2015 to over 820 million people today [1]. Food security is however not only about a sufficient supply of calories per person. It is also about improving diets, addressing the worldwide increase in the prevalence of obesity, and how we use and value environmental goods and services.

© Paulus Rusyanto | Dreamstime.com

Agriculture, forestry and other land use currently account for around 24% of greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activities [2]. Land use changes are also a major driver behind the worldwide loss of biodiversity [3]. Clearly, in light of population growth and the increasingly visible fingerprints of a human-induced global climate crisis and other environmental changes, business as usual is not an option.

Systems thinking is key in shifting towards more sustainable practices. A new report released by the Food and Land-Use System (FOLU) Coalition showcases that there is much to be gained. There are massive hidden costs in our current food and land use systems. The report outlines ten critical transitions, which can substantially reduce these hidden costs, thereby generating an economic prize, while improving human and planetary health.

The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) contributed to the analytics underpinning the report [4], applying the Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM) [5]. A “better futures” scenario, which seeks to collectively address development and environmental objectives, was compared to a “current trends” scenario, which is basically a continuation of a business-as-usual scenario. The assessment illustrates that an integrated approach that acknowledges the interactions in the food and land use space, can help identify synergies and manage trade-offs across sectors. For example, shifting towards healthy diets not only improves human health, but also reduces pressure on land, thereby helping to improve the solution space for addressing climate change and halting biodiversity loss.

While understanding that the global picture is important, practical solutions require engagement with national and subnational governments. The challenge is to identify development pathways that address the development needs and aspirations of countries within global sustainability contexts. As part of FOLU, the Food, Agriculture, Biodiversity, Land and Energy (FABLE) Consortium was initiated to do exactly this. The FABLE Secretariat, jointly hosted by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) and IIASA, is working with knowledge institutions from developed and developing countries, to explore the interactions between national and global level objectives and their implications for pathways towards sustainable food and land use systems. Preliminary results from inter-active scenario and development planning exercises, so-called Scenathons, were recently presented in the FABLE 2019 report.

These initiatives highlight that acknowledging and embracing complexity can help reconcile development and environmental interests. This also entails rethinking how we relate to and manage nature’s services and their role in providing the foundation for the welfare of current and future generations. This is underscored by the prominent role nature-based solutions are given at the UN Secretary General’s Climate Action Summit. We need to move from silo-based, sector specific, single objective approaches to a focus on multiple objective solutions. In the land use space, this means embedding agriculture in the broader land use context, which accounts for and values environmental services, and linking to the food system where dietary choices shape human health and the demand for land.

Doing so will help bridge the international policy objectives of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the UN Convention on Combating Desertification (UNCCD), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) enshrined in ‘The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’. This represents an opportunity to create a new value proposition for agriculture and other land use activities where environmental stewardship is rewarded.

References

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) et al. (2019). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019. Safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns. Rome, FAO.

[2] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2019). Climate Change and Land. IPCC Special Report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

[3] Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (2018). The IPBES assessment report on land degradation and restoration. Montanarella, L., Scholes, R., and Brainich, A. (eds.). Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, Germany. 744 pages.

[4] Deppermann, A. et al. 2019. Towards sustainable food and land-use systems: Insights from integrated scenarios of the Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM). Supplemental Paper to The 2019 Global Consultation Report of the Food and Land Use Coalition Growing Better: Ten Critical Transitions to Transform Food and Land Use. Laxenburg, IIASA.

[5] Havlik P, Valin H, Herrero M, Obersteiner M, Schmid E, Rufino MC, Mosnier A, Thornton PK, et al. (2014). Climate change mitigation through livestock system transitions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (10): 3709-3714. DOI: 1073/pnas.1308044111 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/10970].

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 6, 2019 | Data and Methods, Ecosystems, Systems Analysis, Young Scientists

By Davit Stepanyan, PhD candidate and research associate at Humboldt University of Berlin, International Agricultural Trade and Development Group and 2019 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) Award Finalist.

Participating in the YSSP at IIASA was the biggest boost to my scientific career and has shifted my research to a whole new level. IIASA provides a perfect research environment, especially for young researchers who are at the beginning of their career paths and helps to shape and integrate their scientific ideas and discoveries into the global research community. Being surrounded by leading scientists in the field of systems analysis who were open to discuss my ideas and who encouraged me to look at my own research from different angles was the most important push during my PhD studies. Having the work I did at IIASA recognized with an Honorable Mention in the 2019 YSSP Awards has motivated me to continue digging deeper into the world of systems analysis and to pursue new challenges.

© Davit Stepanyan

Although my background is in economics, mathematics has always been my passion. When I started my PhD studies, I decided to combine these two disciplines by taking on the challenge of developing an efficient method of quantifying uncertainties in large-scale economic simulation models, and so drastically reduce the need and cost of big data computers and data management.

The discourse on uncertainty has always been central to many fields of science from cosmology to economics. In our daily lives when making decisions we also consider uncertainty, even if subconsciously: We will often ask ourselves questions like “What if…?”, “What is the chance of…?” etc. These questions and their answers are also crucial to systems analysis since the final goal is to represent our objectives in models as close to reality as possible.

I applied for the YSSP during my third year of PhD research. I had reached the stage where I had developed the theoretical framework for my method, and it was the time to test it on well-established large-scale simulation models. The IIASA Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM), is a simulation model with global coverage: It is the perfect example of a large-scale simulation model that has faced difficulties applying burdensome uncertainty quantification techniques (e.g. Monte Carlo or quasi-Monte Carlo).

The results from GLOBIOM have been very successful; my proposed method was able to produce high-quality results using only about 4% of the computer and data storage capacities of the above-mentioned existing methods. Since my stay at IIASA, I have successfully applied my proposed method to two other large-scale simulation models. These results are in the process of becoming a scientific publication and hopefully will benefit many other users of large-scale simulation models.

Looking forward, despite computer capacities developing at high speed, in a time of ‘big data’ we can anticipate that simulation models will grow in size and scope to such an extent that more efficient methods will be required.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 14, 2018 | Ecosystems, Environment, Systems Analysis

By Alma Mendoza, Colosio Fellow with the IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Changes in land use cover can have a crucial impact on the environment in terms of biodiversity and the benefits that ecosystems provide to people. Assessing, quantifying, and identifying where these changes are the most drastic is especially important in countries that have high biodiversity along with high rates of natural vegetation loss. Socioeconomic pressures often drive land use change and the impacts are expected to increase due to population growth and climate change.

To better understand the possible impacts of land use change in Mexico over the short, medium, and long term, my colleagues and I used the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways–a set of pathways that span a wide range of feasible future developments in areas such as agriculture, population, and the economy–together with a set of climatic scenarios known as the Representative Concentration Pathways. We focused on Mexico, because the country is large enough to encompass different ecosystems, socioeconomic characteristics, and climates. In addition, Mexico is characterized by high deforestation rates, huge biodiversity, and a large number of communities with contrasting land management practices. Incorporating all these features, allowed us to take the complexity of socioecological systems into account.

We designed a model to test how socioeconomic and biophysical drivers, like slope or altitude, may unfold under different scenarios and affect land use. Our model includes 13 categories of which eight represent the most important ecosystems in Mexico (temperate forests, cloud forests, mangroves, scrublands, tropical evergreen and -dry forests, natural grasslands, and other vegetation such as desert ecosystems or natural palms), four represent anthropogenic uses (pasture, rainfed and irrigated agriculture, and human settlements), and one constitutes barren lands. We set two plausible scenarios: “Business as usual” and an optimistic scenario called the “green scenario”. We projected the “business as usual” scenario using medium rates of vegetation loss based on historical trends and combined it with a medium population and economic growth with medium increases in climatic conditions. For the “green scenario”, we projected the lowest rates of native vegetation loss and the highest rates of native vegetation recovery with a low population and medium economic growth in a future with low climatic changes.

Skyline of Mexico City © Shane Adams | Dreamstime.com

Our results show that natural vegetation will undergo significant reductions in Mexico and that different types of vegetation will be affected differently. Tropical dry and evergreen forests, followed by ‘other’ vegetation and cloud forests are the most vulnerable ecosystems in the country. For example, according to the “business as usual” scenario, tropical dry forests might decrease in extent by 47% by the end of the century. This is extremely important considering that the most recent rates, for the period 2007 to 2011, were even higher than the medium rates we used in this scenario. In contrast, the “green scenario” allowed us to see that, with feasible changes of rate, this ecosystem could increase their distribution. However, even 80 years of regeneration would not be enough to reach the extent these forests had in 1985, when they accounted for around 12% of land cover in Mexico. Moreover, the expansion of anthropogenic land cover (such as agriculture, pastures, and human settlements) might reach 37% of land cover in the country by 2050 and 43% by 2100 under the same scenario. In terms of CO2 emissions due to land use cover change we found that Mexico was responsible for 1-2% of global emissions that are the result of land use cover change, but by 2100 it could account for as much as 5%.

Our findings show that conservation policies have not been effective enough to avoid land use cover change, especially in tropical evergreen forests and drier ecosystems such as tropical dry forests, natural grasslands, and other vegetation. Cloud forests have also been badly affected. As a biologically and culturally rich country, Mexico is responsible for maintaining its diversity by implementing a sustainable and intelligent management of its territory.

Our study identified hotspots of land use change that can help to prioritize areas for improving environmental performance. Our project is currently linking the hotspots of change with the most threatened and endemic species of Mexican terrestrial vertebrates (mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and birds) to provide useful results that can help prioritize ecosystems, species, or municipalities in Mexico.

Reference:

Mendoza Ponce A, Corona-Núñez R, Kraxner F, Leduc S, & Patrizio P (2018). Identifying effects of land use cover changes and climate change on terrestrial ecosystems and carbon stocks in Mexico. Global Environmental Change 53: 12-23. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15462]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 7, 2018 | Ecosystems

Marcia MacNeil, Blogger at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), on a new comprehensive review by IFPRI and IIASA researchers

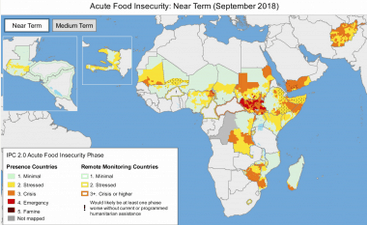

The world’s agricultural monitoring systems provide up-to-date information on food production to decision makers that is crucial to global and national food security. When prices become dangerously volatile—as they did during the food price crisis of 2007-2011—these systems spread critical information quickly that can reduce the risks of market and supply upheavals.

Monitoring is now better than ever, with improved access to the latest high-resolution satellite imagery and remote-sensing based products. But fundamental gaps remain, and no system currently provides the quantitative crop area and production forecasts ideally needed for food security interventions, according to a comprehensive review by experts including IFPRI Senior Research Fellow Liangzhi You, and led by IIASA researchers in the Ecosystems Services and Management Program

You and his coauthors reviewed the eight principal global and regional scale agricultural monitoring systems currently in operation: The Global Information and Early Warning System (GIEWS), USAID’s Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), the MARS Crop Yield Forecasting System (MCYFS), China’s CropWatch, the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Foreign Agricultural Service (USDA-FAS), the World Food Programme Seasonal Monitor, and Anomaly Hot Spots of Agricultural Production (ASAP).

Using questionnaires and discussions with monitoring systems staff, the study measured the gaps in input data and models used, outputs produced, the role of the analysts, interaction with other systems, and the geographical scale at which the systems operate.

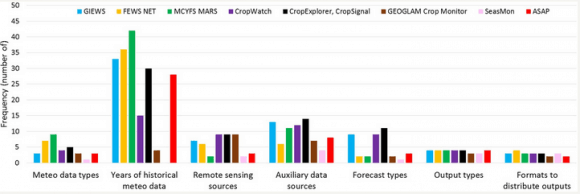

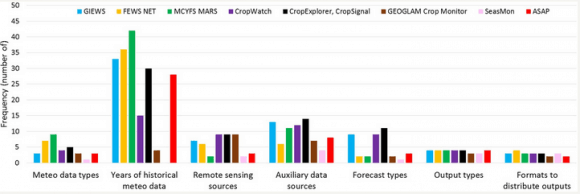

Figure 1. Agricultural Systems. Comparison of global and regional scale agricultural monitoring systems in terms of number of sources of input data used.

They found that although each system is tailored to meet the needs of different customers, there are many similarities between the systems. For example, nearly all the reviewed systems reported that cropland maps, crop calendars, and meteorological data were their most important sources.

The most glaring gaps among the systems were found in the data used for crop calendars and crop type maps.

Crop calendars list planting and harvesting dates for the crop types in a particular area. This information is key for keeping tabs on crop conditions, estimating farming area, forecasting yields, and more. It’s used to make decisions to mobilize food aid and move commodities to market, reducing food waste. But this data comes in many different, at-times incompatible forms.

Some data comes from household surveys and censuses, some from expert opinions, and some from satellites. This lack of consistent, validated data results in poor representation of geographic diversity and variability in location and timing in sowing and harvesting dates. Maps of crop types, another important source of data for monitoring systems, suffer from a similar lack of consistent data.

The world’s crop monitoring systems would benefit from greater data sharing, the study concludes—such as a shared repository of datasets. Opportunities for more precise data collection abound. The rapid rise in the use of smart phones and social media, even in once-inaccessible rural areas, offers opportunities for farmers to self-report geo-located crops and information such as planting dates, fertilizer application, irrigation, and expected yields.

Climate change raises the risks to crop production, and these monitoring systems are increasingly critical for decision making and early warning to head off future food crises. More, and better high-quality data will help ensure they can quickly and accurately produce potentially life-saving information.

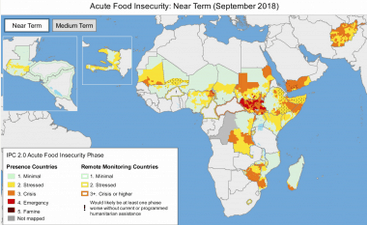

Figure 2. An image from the USAID Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) shows areas of acute near-term food insecurity. Such systems are crucial to monitoring and responding to potential food crises, but gaps remain, particularly for certain crops.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

This blog post was originally published on https://www.ifpri.org/blog/new-review-finds-fundamental-gaps-and-new-opportunities-worlds-agricultural-monitoring-systems

Reference

Fritz S, See L, Bayas JCB, Waldner F, Jacques D, Becker-Reshef I, Whitcraft A, Baruth B, et al. (2018). A comparison of global agricultural monitoring systems and current gaps. Agricultural Systems DOI:10.1016/j.agsy.2018.05.010. (In Press)

Nov 2, 2018 | Citizen Science, Ecosystems, Environment, Food

by Rastislav Skalsky, Ecosystems Services and Management Program, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Clay soil

As growers, we know soil is important. It supports plants, and provides nutrients and water for them to grow. But do we all appreciate how crucial the role of soil is in continuously supplying plants with water, even when it hasn’t rained for a few days or even weeks, even without extra water being added via watering?

Soil is like a sponge. It can retain rain water and, if it is not taken up by plants, soil can store it for a long time. We can feel the water in soil as soil moisture. Try it — take and hold a lump (clod) of soil — if it is wet it will leave a spot on your palm. If it’s only moist then it will feel cold — cooler than the air around. And if the soil is dry, it will feel a little warm.

Soil moisture not only can be felt, but it can also be measured — in the lab, or directly in the field with professional or low-cost soil moisture sensors.

Soil moisture in general indicates how much water is contained by the soil. But it is not always the case that soil which feels moist or wet is able to support plants. It could happen that, despite feeling moist, the soil simply does not hold enough water, or holds the water too tightly for the plants to extract it. Or the opposite, soil can sometimes contain too much water. To understand how this works, one has to learn more about how water is stored in the soil.

Water is bound to soil by physical forces. Some forces are too weak to hold water in the plant root zone and water percolates to deeper layers, where plants can no longer reach it. Other forces can be too strong, preventing water from being retrieved by the roots.

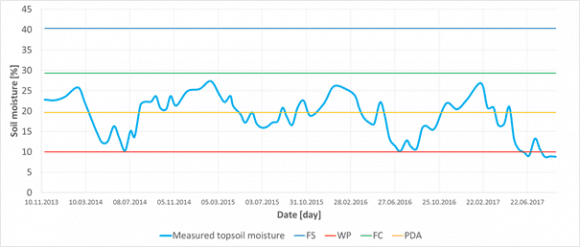

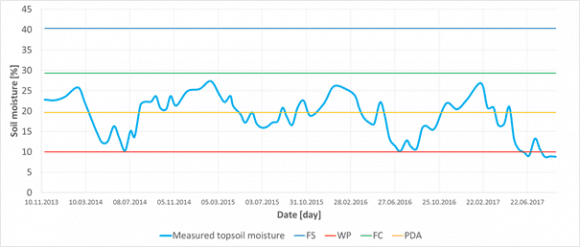

Figure 1

If soil moisture is measured at one place over time, it can reveal its seasonal dynamics. Having estimated important soil water content thresholds (FS — full saturation, FC — field capacity, PDA — point of decreased availability, and WP — wilting point) for that particular site, e.g. based on soil texture test or measurement, one can easily interpret if the measured soil moisture and say if there was enough water or not to fully support plants with water and air. In this particular case of sandy 0–30 cm deep topsoil from Slovakia, it was never wet enough to cause oxygen stress for plants, — in fact it never reached state of all capillary voids filled with water (FC). On the other hand, each summer the topsoil moisture dropped below the point of decreased availability (PDA), even got close to the wilting point or went through (WP), which means that during those periods plants suffered drought conditions.

Thresholds

In order to describe this behavior in more useful terms, plant ecologists and soil hydrologists came up with couple of important soil water content thresholds (Figure 1). These thresholds, also called “soil moisture ecological intervals”, define how easily plants can get the water out of the soil.

We speak about full saturation of soil when all empty spaces (pores/voids) are completely filled with water. Full saturation of the soil with water prevents air entering into the soil. Yet there is no force holding water in the soil. Roots need air as well as water so, if this situation continues, it eventually causes oxygen stress for most of the common plants because roots simply cannot breathe.

Soil also has different types of pores. Larger ones, which are called “gravitational pores”, are filled with water only when the soil is saturated and otherwise drains freely, and smaller ones called “capillary pores” which are small enough in size to prevent water from percolating down the soil profile by gravitation. These smaller pores can hold water even in well-drained soils and make it available for plants to extract. There are also even smaller pores where the water is held so tightly that plants cannot extract it.

Sandy soil

When all gravitational pores/voids are empty of water and it is present only in so called capillary pores/void we speak about the field water capacity — which is considered to be the best soil moisture status of the soil — enabling plants to retrieve the water they need, whilst leaving enough air for roots to breathe. If no new water is added into the soil, the soil dries as water is used by plants or evaporates. As soil dries less water is available to plants until the point of decreased availability when water remains only in the smallest capillary pores/voids. But this water is bound to soil particles so strongly that most plants are not able to extract it suffer from drought. Ultimately, all the available water is used up by plants, and the remaining water is inaccessible. Soil reaches the so-called wilting point and water is not available for the plants anymore. Plants permanently wilt and eventually die.

How Soil Characteristics Relate to Moisture

The tricky thing with soil moisture however is that the same amount of water (volumetric percent of the total soil column volume) can, in different soils, represent different amount of water available for plants. How big this difference could be is defined by many soil characteristics.

Loamy soil

The most important is the soil texture — a blend of all fine-earth soil mineral constituents (sand, silt, clay) and stones in various rates. In general, the finer the texture is (i.e. more clay, less sand) the more water is bound in the soil too tightly to be retrieved by plants. Even if the soil feels moist, plants can permanently wilt in clay soils. In contrast, those soils with coarse texture (i.e. more sand, less clay) can support plants with nearly all the water they can hold. Although the soil looks dry, plants can still effectively take the water out of it. The drawback here is that in coarse textured, sandy, soil nearly all water drains down the gravitational pores and therefore such a soil cannot support plants for very long time. That is also why medium textured soils (loam, silty loam, clay loam) are considered best for holding and providing the water for plants. Medium textured soils can effectively drain excess water, yet hold much water in capillary pores/voids for a long time, and still, only a relatively small amount of water remains unavailable for the plants.

A practical implication of this behavior of soil with different soil texture could be that one has to apply slightly different strategies to maintain soil moisture in the way that it can effectively supply plants with water. Sandy soils will require more frequent watering with smaller amount of water. It would not make any practical sense to try build-up a storage of water in these soils. All extra water added will simply drain out of the topsoil. Clay rich soils can absorb big amounts of water but a lot is bounded too strongly to the soil particles and thus not available for the plants. Therefore one should water even if the soil looks moist or wet — and if dry a lot of water must be added to recharge the topsoil so that it can support plants effectively. With loamy soils it is possible to be more relaxed with watering frequency, simply because one can build solid storage of water in such soils. Adding a bit more water than is necessary is perfectly fine with these soils because the water is effectively kept in the soil profile and it can be used later on.

Interested in learning more? Why not sign up for GROW Observatory’s next free online course – Citizen Research: From Data to Action – to discover how citizen-generated data on soils, food and a changing climate can create positive change in the world. Starts 5th November.

This blog was originally published on https://medium.com/grow-observatory-blog/moisture-matters-a9e33dc880a1

Oct 5, 2018 | Climate, Climate Change, Ecosystems, Environment, Food, Food & Water, History, Young Scientists

© Marcus Thomson

By Marcus Thomson, researcher, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

While living in Cairo in 2010, I witnessed first-hand the human toll of political and environmental disasters that washed over Africa at the end of the last century. Unprecedented numbers of migrants were pressing into North Africa, many pushed out of their homelands by conflict and state-failure, pulled towards safer, richer, less fragile places like Europe. Throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, climate change was driving up competition for scarce land and water, and raising pressure on farmers to maintain the quantity and quality of their crops.

It is a similar story throughout the developing world, where many farmers do without the use of expensive chemical fertilizer and pesticides, complex irrigation, or boutique seed varieties. They rely instead on traditional land management practices that developed over long periods with consistent, predictable conditions. It is difficult to predict how dryland farmers will respond to climate change; so it is challenging to plan for various social, economic, and political problems expected to develop under, or be exacerbated by, climate change. Will it spur innovation or, as has been argued for the Syrian civil war[1], set up conflict? A major stumbling block is that the dynamics of human social behavior are so difficult to model.

Instead of attempting to predict farmers’ responses to climate change by modelling human behavior, we can look to the responses to environmental changes of farmers from the past as analogues for many subsistence farmers of the future. Methods to fill in historical gaps, and reconstruct the prehistoric record, are valuable because they expand the set of observed cases of societal-scale responses to environmental change. For instance, some 2000 years ago, an expansive maize-growing cultural complex, the Ancestral Puebloans (APs), was well established in the arid American Southwest. By AD 1000, members of this AP complex produced unique and innovative material culture including the famed “Great Houses”, the largest built structures in the United States until the 19th century. However, between AD 1150 and 1350, there was a profound demographic transformation throughout the Southwest linked to climate change. We now know that many APs migrated elsewhere. As a PhD student at the University of California, Los Angeles, I wondered whether a shift to cooler, more variable conditions of the “Little Ice Age” (LIA, roughly AD 1300 to 1850) was linked to the production of their staple crop, maize.

I came to IIASA as a YSSP in 2016 to collaborate with crop modelers on this question, and our work has just been published in the journal Quaternary International.[2] I brought with me high-resolution data from a state-of-the-art climate model to drive the crop simulations, and AP site information collected by archaeologists. Because AP maize was quite different from modern corn, I worked with IIASA soil scientist Juraj Balkovič to modify the crop simulator with parameters derived from heirloom varieties still grown by indigenous peoples in the Southwest. I and IIASA economic geographer Tamás Krisztin developed a statistical technique to analyze the dynamical relationship between AP site occupation and simulated yield outcomes.

We found that for the most climate-stressed high-elevation sites, abandonments were most associated with increased year-to-year yield variability; and for the least stressed low-elevation and well-watered sites, abandonment was more likely due to endogenous stressors, such as soil degradation and population pressure. Crucially, we found that across all regions, populations peaked during periods of the most stable year-to-year crop yields, even though these were also relatively warm and dry periods. In short, we found that AP maize farmers adapted well to gradually rising temperatures and drought, during the MCA, but failed to adapt to increased climate variability after ~AD 1150, during the LIA. Because increased variability is one of the near certainties for dryland farming zones under global warming, the AP experience offers a cautionary example of the limits of low-technology adaptation to climate change, a business-as-usual direction for many sub-Saharan dryland farmers.

This is a lesson from the past that policymakers might take note of.

[1] Kelley, C. P., Mohtadi, S., Cane, M. A., Seager, R., & Kushnir, Y. (2015). Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201421533.

[2] Thomson, M. J., Balkovič, J., Krisztin, T., MacDonald, G. M. (2018). Simulated crop yield for Zea mays for Fremont Ancestral Puebloan sites in Utah between 850-1499 CE based on temperature dailies from a statistically downscaled climate model. Quaternary International. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2018.09.031

You must be logged in to post a comment.