by Rastislav Skalsky, Ecosystems Services and Management Program, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Clay soil

As growers, we know soil is important. It supports plants, and provides nutrients and water for them to grow. But do we all appreciate how crucial the role of soil is in continuously supplying plants with water, even when it hasn’t rained for a few days or even weeks, even without extra water being added via watering?

Soil is like a sponge. It can retain rain water and, if it is not taken up by plants, soil can store it for a long time. We can feel the water in soil as soil moisture. Try it — take and hold a lump (clod) of soil — if it is wet it will leave a spot on your palm. If it’s only moist then it will feel cold — cooler than the air around. And if the soil is dry, it will feel a little warm.

Soil moisture not only can be felt, but it can also be measured — in the lab, or directly in the field with professional or low-cost soil moisture sensors.

Soil moisture in general indicates how much water is contained by the soil. But it is not always the case that soil which feels moist or wet is able to support plants. It could happen that, despite feeling moist, the soil simply does not hold enough water, or holds the water too tightly for the plants to extract it. Or the opposite, soil can sometimes contain too much water. To understand how this works, one has to learn more about how water is stored in the soil.

Water is bound to soil by physical forces. Some forces are too weak to hold water in the plant root zone and water percolates to deeper layers, where plants can no longer reach it. Other forces can be too strong, preventing water from being retrieved by the roots.

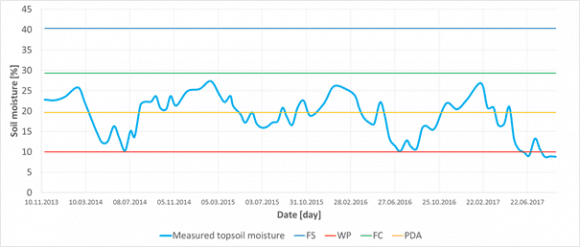

Figure 1

If soil moisture is measured at one place over time, it can reveal its seasonal dynamics. Having estimated important soil water content thresholds (FS — full saturation, FC — field capacity, PDA — point of decreased availability, and WP — wilting point) for that particular site, e.g. based on soil texture test or measurement, one can easily interpret if the measured soil moisture and say if there was enough water or not to fully support plants with water and air. In this particular case of sandy 0–30 cm deep topsoil from Slovakia, it was never wet enough to cause oxygen stress for plants, — in fact it never reached state of all capillary voids filled with water (FC). On the other hand, each summer the topsoil moisture dropped below the point of decreased availability (PDA), even got close to the wilting point or went through (WP), which means that during those periods plants suffered drought conditions.

Thresholds

In order to describe this behavior in more useful terms, plant ecologists and soil hydrologists came up with couple of important soil water content thresholds (Figure 1). These thresholds, also called “soil moisture ecological intervals”, define how easily plants can get the water out of the soil.

We speak about full saturation of soil when all empty spaces (pores/voids) are completely filled with water. Full saturation of the soil with water prevents air entering into the soil. Yet there is no force holding water in the soil. Roots need air as well as water so, if this situation continues, it eventually causes oxygen stress for most of the common plants because roots simply cannot breathe.

Soil also has different types of pores. Larger ones, which are called “gravitational pores”, are filled with water only when the soil is saturated and otherwise drains freely, and smaller ones called “capillary pores” which are small enough in size to prevent water from percolating down the soil profile by gravitation. These smaller pores can hold water even in well-drained soils and make it available for plants to extract. There are also even smaller pores where the water is held so tightly that plants cannot extract it.

Sandy soil

When all gravitational pores/voids are empty of water and it is present only in so called capillary pores/void we speak about the field water capacity — which is considered to be the best soil moisture status of the soil — enabling plants to retrieve the water they need, whilst leaving enough air for roots to breathe. If no new water is added into the soil, the soil dries as water is used by plants or evaporates. As soil dries less water is available to plants until the point of decreased availability when water remains only in the smallest capillary pores/voids. But this water is bound to soil particles so strongly that most plants are not able to extract it suffer from drought. Ultimately, all the available water is used up by plants, and the remaining water is inaccessible. Soil reaches the so-called wilting point and water is not available for the plants anymore. Plants permanently wilt and eventually die.

How Soil Characteristics Relate to Moisture

The tricky thing with soil moisture however is that the same amount of water (volumetric percent of the total soil column volume) can, in different soils, represent different amount of water available for plants. How big this difference could be is defined by many soil characteristics.

Loamy soil

The most important is the soil texture — a blend of all fine-earth soil mineral constituents (sand, silt, clay) and stones in various rates. In general, the finer the texture is (i.e. more clay, less sand) the more water is bound in the soil too tightly to be retrieved by plants. Even if the soil feels moist, plants can permanently wilt in clay soils. In contrast, those soils with coarse texture (i.e. more sand, less clay) can support plants with nearly all the water they can hold. Although the soil looks dry, plants can still effectively take the water out of it. The drawback here is that in coarse textured, sandy, soil nearly all water drains down the gravitational pores and therefore such a soil cannot support plants for very long time. That is also why medium textured soils (loam, silty loam, clay loam) are considered best for holding and providing the water for plants. Medium textured soils can effectively drain excess water, yet hold much water in capillary pores/voids for a long time, and still, only a relatively small amount of water remains unavailable for the plants.

A practical implication of this behavior of soil with different soil texture could be that one has to apply slightly different strategies to maintain soil moisture in the way that it can effectively supply plants with water. Sandy soils will require more frequent watering with smaller amount of water. It would not make any practical sense to try build-up a storage of water in these soils. All extra water added will simply drain out of the topsoil. Clay rich soils can absorb big amounts of water but a lot is bounded too strongly to the soil particles and thus not available for the plants. Therefore one should water even if the soil looks moist or wet — and if dry a lot of water must be added to recharge the topsoil so that it can support plants effectively. With loamy soils it is possible to be more relaxed with watering frequency, simply because one can build solid storage of water in such soils. Adding a bit more water than is necessary is perfectly fine with these soils because the water is effectively kept in the soil profile and it can be used later on.

Interested in learning more? Why not sign up for GROW Observatory’s next free online course – Citizen Research: From Data to Action – to discover how citizen-generated data on soils, food and a changing climate can create positive change in the world. Starts 5th November.

This blog was originally published on https://medium.com/grow-observatory-blog/moisture-matters-a9e33dc880a1

You must be logged in to post a comment.