Jan 17, 2020 | Climate Change, Demography

By Roman Hoffmann, Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW, and University of Vienna), Vienna Institute of Demography, Austrian Academy of Sciences, and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

Taking action to combat climate change and its impacts is urgent and vital to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Although per capita emissions are still highest in high-income countries, several emerging low and middle-income countries have seen a rise in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions in recent years. While much of that rise was due to increased (export-oriented) industrial activities, changing lifestyle, consumption, and mobility patterns also played a significant role. How people can be encouraged to behave in an environmentally friendly way is a fundamental question for climate change mitigation. Despite a call for a stronger emphasis on demand-side solutions in mitigation strategies, little is known about the determinants of pro-environmental behaviors of people from the developing world.

© Roman Hoffman | IIASA

In a study with IIASA researcher Raya Muttarak, which has recently been published in Environmental Research Letters, we found that education significantly contributes to increasing pro-environmental orientations and actions among low-income households in the Philippines. As an emerging lower-middle-income country, the Philippines are faced with severe environmental issues, such as pollution, deforestation, and environmental degradation. Already in the 1990s, public policy has responded to these challenges by developing several environmentally-focused learning initiatives and by making environmental education a fundamental pillar of the national school curriculum. Today, according to the World Value Survey, more than 73% of the population can identify with a person who gives importance to looking after the environment compared to 55% and 63% in the neighboring countries Thailand and Malaysia, respectively.

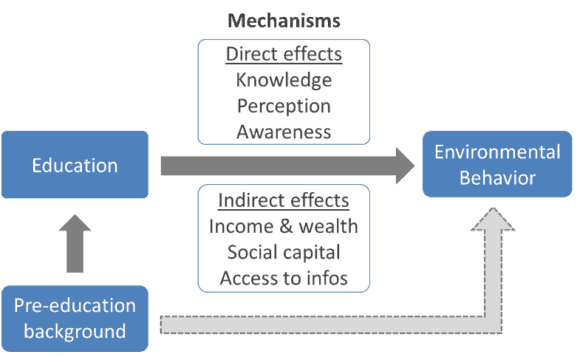

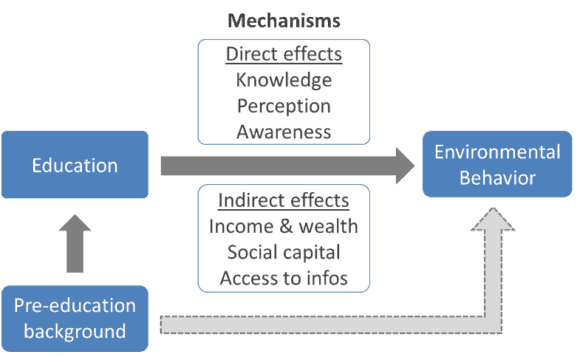

Figure 1 – Conceptual framework explaining the direct and indirect channels through which education influences environmental behavior. Note: The empirical design controls for the respondents’ pre-education background and indirect channels of influence allowing us to capture the direct effects of education on pro-environmental behaviors.

Based on original cross-sectional survey data, we found education to be positively related to pro-environmental behaviors such as recycling, proper garbage disposal, and planting trees. An additional year of schooling is estimated to increase the probability of carrying out climate-friendly actions by a substantial 3.3%. Going beyond previous research, we explored some of the underlying mechanisms through which education influences environmental behavior. . While knowledge and awareness raising are both important, it is found that education influences behavior mainly by increasing awareness about the anthropogenic causes of climate change, which may consequently affect the individual perception of self-efficacy in reducing human impacts on the environment. This is in line with the environmental psychology literature, which finds that poor understanding of the connection between human actions and climate change influences the perception of one’s ability to control and take action against it. People will become active only if the perceived likelihood of achieving a desired outcome is high enough. Education can hence play a vital role in promoting a better understanding of climate change and in raising awareness about the impacts of human activities.

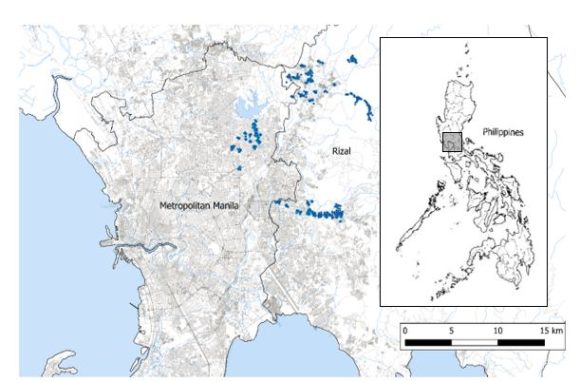

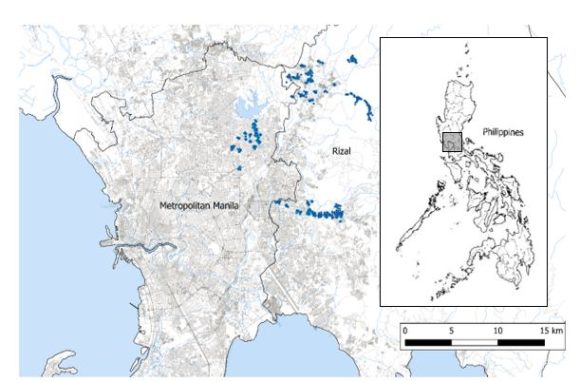

Figure 2 – Map of study areas with locations of respondents’ homes. The study areas encompassed both more urban and rural areas located in Rizal province towards the East of the National Capital Region

In line with recent efforts of the international community to promote education for sustainable development, our study provides solid empirical evidence confirming the important role of education in climate change mitigation efforts. Investments in education can make an important contribution in raising awareness and ultimately in promoting green behavior helping to reduce the human impacts on the global climate system. In this regard, while it is important to provide learners with the necessary tools and capabilities to undertake pro-environmental actions, it is also key to raise their perceived self-efficacy. Education should thus not only focus on the transfer of knowledge and information, but also highlight the importance of the individual contribution in mitigating the harmful consequences of global environmental change.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 23, 2019 | Austria, Science and Policy

By Jan Marco Müller, IIASA Acting Chief Operations Officer

Jan Marco Müller shares his insights into the recent high-level forum in Vienna that brought together science advisors to ministers of foreign affairs from across the world and other experts in the practice, theory, and discussion of science diplomacy.

Established following an initiative by the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, IIASA can be considered a child of diplomacy for science. At the same time, the institute has always been one of the world’s premier vehicles of science for diplomacy, by using science to build bridges between nations including those with special relations. However, there is another dimension of science diplomacy which has gained traction in recent years: the support scientists can provide to diplomats and policymakers in the foreign policy domain – known as science in diplomacy.

© IIASA

As global challenges become more complex and interdependent and technological progress advances at an ever-increasing speed, the scientific-technical dimension of foreign policies has gained increasing attention. This is illustrated by four examples:

- Climate change impacts everybody on the planet, regardless of national borders.

- Many digital technologies escape national jurisdictions and so create tensions between nations: e.g. cryptocurrencies, deep fakes, and internet trolls.

- Trade agreements are often hampered by disagreements on technical standards, which themselves are influenced by societal values: people may still remember the discussions around chlorinated chicken in the US-EU trade negotiations a few years ago.

- National interests are increasingly entering international spaces, which in the past have been governed by science, such as the Arctic/Antarctic, the deep sea and outer space.

Ministries of foreign affairs and diplomatic services around the world are all confronted with similar issues and critically depend on advice provided by scientists.

With this in mind, on 25-26 November 2019 IIASA, together with the International Network for Government Science Advice (INGSA), the Austrian Federal Ministry of Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs, the Diplomatische Akademie Wien (Vienna School of International Studies), and the Natural History Museum Vienna, held the global meeting of the Foreign Ministries Science & Technology Advice Network (FMSTAN).

FMSTAN gathers science advisors to ministers of foreign affairs from around the planet, providing a platform for the exchange of information and best practices. IIASA hosted the first meeting of this network in October 2016, which has since grown significantly, with some 50 countries now participating in its biannual meetings.

The global meeting in November was organized back to back with the meetings of two other important networks in the science diplomacy arena: the Science Policy in Diplomacy and External Relations Network (SPIDER) – which is the science diplomacy branch of the International Network for Government Science Advice – and the Big Research Infrastructures for Diplomacy and Global Engagement through Science (BRIDGES) Network. BRIDGES was established a year ago following an initiative by my colleague Maurizio Bona at CERN and myself, with the aim of uniting the science diplomacy officers of all major international research infrastructures. In addition, a 3-day training course organized by the EU-funded project Using science for/in diplomacy for addressing global challenges (S4D4C) was arranged in parallel to achieve maximum synergies.

© IIASA (L-R): Jan Marco Müller and Jeffrey Sachs, Special Advisor to the UN Secretary-General on SDGs; Director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, NY.

The meetings were attended by around 100 science diplomats including the President-elect of the International Science Council Sir Peter Gluckman, the UN Advisor on the Sustainable Development Goals Jeffrey Sachs, the former Rector of the University for Peace of the UN Martin Lees, the S&T Advisor to the US Secretary of State Matt Chessen, the S&T Advisor to the Japanese Foreign Minister Teruo Kishi, the Science Diplomacy Advisor to the Mexican Foreign Minister José Ramón López Portillo, and the Chief Science Advisor in the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs Dirk-Jan Koch, to name just a few.

Six major topics were discussed:

- The role of science diplomacy in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

- The importance of science in international security policies

- The challenges for science diplomacy in the current geopolitical environment

- Technology Diplomacy

- The role of science in diplomatic curricula (and vice versa)

- Future challenges for science diplomacy and the role of systemic thinking in policymaking

The Vienna meeting offered a unique platform for all those who “speak science” in the diplomatic arena to exchange ideas and experiences, while fostering a common global agenda. For additional insights I recommend reading the piece “Science Diplomacy: A Pragmatic Perspective from the Inside” which aims at making the term science diplomacy more operational – all the four authors participated to the Vienna meeting.

Overall the event demonstrated once again the convening power of IIASA and the leadership of the institute in confirming Vienna as one of the global hubs for science diplomacy.

© Mahmood | BMEIA. FMSTAN/SPIDER members and participants of the S4D4C training course.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 18, 2019 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience

Making use of mutuality-solidarity-accountability-transparency principles

By Teresa M. Deubelli, researcher in the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program and Reinhard Mechler, Deputy Program Director IIASA Risk and Resilience Program

The Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) for Loss and Damage and its ongoing review were hot topics at COP25. Hopes for a step-change on the issue of finance to scale up action and support have not been translated into action. Negotiating Parties remain divided over the way forward and the question of what kind of finance and for whom. We suggest to build on principles of risk governance, including insurance, and international cooperation – mutuality, solidarity, accountability and transparency – and to combine these in novel ways in order to upscale action on both averting and minimizing as well as addressing loss and damage under the WIM in a manner that truly shows responsibility for responding to the climate crisis.

COP25 Madrid, Spain © Reinhard Mechler | IIASA

Why do we need a step-change on Loss and Damage finance?

Hard limits to adaptation are creating situations beyond adaptation; think for example of communities fleeing desertification or sea-level rise that can only retreat so far. The WIM has made substantial strides on its objectives to advance knowledge and exchange since its creation, but now the time is ripe to take the necessary steps to also move forward on addressing loss and damage from climate change.

So far, this third WIM priority has mostly been addressed through insurance approaches, such as the Fiji Clearing House. While there is value in scaling up risk transfer options, insurance comes with drawbacks: insurance premium costs often exceed financial capacities of vulnerable groups or may result in a false sense of protection that undermines further resilience-building action. Additionally, risk transfer options remain focused on sudden onset events.

Loss and damage from climate change is not just linked to sudden events; sea-level rise, desertification, and glacial melting take years to unfold, but once these tipping points are reached, recovery and reconstruction, and thus the typical logic of humanitarian assistance, are out of the question. As the climate crisis spirals forward tipping points may be reached sooner than expected, also challenging the sustainability of resilience building actions within the framework of development cooperation

How to make a principled case to generate support for addressing loss and damage?

Most vulnerable countries agree that the WIM needs to advance on enhancing action and support for addressing loss and damage from climate change. Discussions at COP25 focused heavily on the issue of mobilizing finance for addressing loss and damage, but little headway was made, as views on the exact modalities of finance and its access differ vastly amongst Parties. Unfortunately, this means that the ongoing WIM review faces a certain risk of replicating the stalemate that characterised the Paris Agreement negotiations on the question of liability, when notions of compensatory justice were crossed out from Article 8 at the request of several developed, high emitting countries.

In order to propel the discourse forward in future rounds of climate talks and in the WIM review, We suggest to build on principles of risk governance, including insurance, and international cooperation – mutuality, solidarity, accountability and transparency – and to combine these in novel ways in order to upscale action on both averting and minimizing as well as addressing losses and damages under the WIM:

- As the underlying insurance principle, mutuality is found in risk pooling and sharing – several parties pool funding to mobilize finance for offsetting losses in times of crisis, essentially spreading out and mutualizing risks across participants.

- Solidarity describes the shared responsibility for supporting others in times of hardship. As a principle it underpins development cooperation and humanitarian assistance and is at the heart of the Agenda 2030.

- Accountability links actions with outcomes in a mutually responsible relationship and is motivated by a perceived ethical or legal obligation for supporting each other in addressing climate-attributed loss and damage.

- As a transversal principle, transparency adds itself as a critical enabler of a finance architecture that expands the WIM to support those who are suffering loss and damage in ways that cannot be addressed through business-as-usual.

All principles lend themselves to the WIM as a ground for advancing on its priority to enhance action and support for addressing loss and damage from climate change, but also offer inspiration for thinking out novel ways to advance further.

What could this mean concretely?

These deliberations are not merely theoretical in nature but are seeing attention. For example through the further development of the (ARC) pool, a regional drought pool established in 2012 as a specialised agency of the African Union to help member states improve their planning, preparation and response capacities. Disbursements from the pool support participating governments’ drought relief efforts, with requirements on how these are used (transparency and accountability).

Initial donor funding (solidarity) and ARC member annual premium payments (mutuality) capitalise the ARC. The pool is currently preparing for the launch of an additional capitalization mechanism, the Extreme Climate Facility (ARC-XCF). This would issue climate catastrophe bonds, resulting in pay-outs whenever the index tracking frequency and magnitude of droughts and extreme temperature exceeds a predefined threshold (transparency). While using the capital markets to access additional funding needs, accountability for climate change is factored in to some extent through the international support divested to setting up the mechanism.

The ARC-XCF is one way to address loss and damage and offers practical inspiration for setting up facilities for addressing loss and damage under the WIM. Especially where hard limits are pushed beyond adaptation and traditional insurance is no longer feasible, drawing on the experience from such risk pooling facilities can be useful input for setting up a specific facility under the WIM that supports those at the frontiers of climate change.

In doing so, it will be important to keep the principles of international cooperation and insurance – mutuality, solidarity, accountability and transparency – in mind to equitably address loss and damage, especially where risks are increasingly intolerable and beyond adaptation.

References:

Deubelli, T. and Mechler, R. (2019). Finance for Loss & Damage: Towards a comprehensive principled approach, unpublished.

Linnerooth-Bayer, J. Surminski, S., Bouwer, L., Noy, I., Mechler, R., McQuistan, C. (2018). Insurance as a Response to Loss and Damage? In: Mechler R, Bouwer L, Schinko T, Surminski S, Linnerooth-Bayer J (2018). Loss and Damage from climate change. Concepts, methods and policy options. Springer, Cham: 483-512

Mechler R, Bouwer L, Schinko T, Surminski S, Linnerooth-Bayer J (2018). Loss and Damage from climate change. Concepts, methods and policy options. Springer, Cham.

This blog is reposted from a Flood Resilience Portal blog.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 27, 2019 | Climate, Climate Change, Communication, Environment, IIASA Network, Women in Science

Award-winning climate communicator Katharine Hayhoe, an atmospheric scientist, professor of political science at Texas Tech University, and director of the Climate Center, discusses the importance of effective science communication in overcoming barriers to public acceptance of climate change in a recent interview with Rachel Potter, IIASA communications officer.

© Chris.Soldt | Boston College.MTS.Photography

Q: Can you tell us a bit about your specific areas of research as a scientist?

I study what climate change means to people, in the places where we live: how it is affecting our water supply, our health, our air quality, the integrity of our infrastructure, and other human and natural systems. Often when people think about climate change they think about polar bears or people who are living on low-lying islands in the South Pacific. I bring climate change down from the global scale to the local level because when we understand that it is an ‘everything issue’, that’s when we understand that we need to act.

Q: You have been widely recognized as a remarkable communicator. What do you see as key to effective science communication?

I believe effective communication begins with connecting and identifying shared values, and ends with talking about solutions. With climate change, sometimes people are overt in their opposition by outright saying the science isn’t real. More often however, it is passive opposition where people feel the problem is too big and there is nothing they can do to fix it. We need to present people with solutions that are practical and viable – in other words, actions that they can engage in.

Q: Why is science communication important?

Science communication explains how the world works. Today we are conducting an unprecedented experiment with our planet, the only one we have. Understanding this is one of the most important things anyone can do as a human being living on Earth.

Q: Can you briefly outline what you see as trends in public and political opinion with regard to human-induced climate change?

Our world is becoming increasingly polarized and we are dividing into tribes. It is happening with many issues and in many places around the world. When the world is changing so quickly, many of us feel uncomfortable with the rate of change, so we retreat to a more tribalized, divided society where we feel comfortable. But by doing so, we focus on the tiny fraction of what divides us rather than the vast preponderance of what unites us, because it makes us feel more secure to do so.

Climate change is a casualty of this fracturing, tribalism, and polarization that is happening – most notably in the US because there are only two political parties, so the tribalization there is much more obvious. In the US, the best predictor of whether people agree with the facts that: climate is changing, humans are responsible, and the impacts are serious, is not how much they know about science, it’s simply where they fall on the political spectrum. This politicization of science is also happening in the UK, Austria, across Europe, Canada, Australia, and Brazil.

© IIASA Katherine Hayhoe with members of the IIASA Women in Science Club

Q: How can this polarization and the barriers to dealing with climate change be challenged?

Climate change is a human issue – it doesn’t care if we are liberal or conservative, rich or poor, although the poor are being more affected than the rich. It affects all of us and almost everything we care about. For that reason, we must emphasize what unites us rather than what divides us. We need to challenge the idea that the solutions to climate change pose a bigger threat to our wellbeing, our comfort, the quality of our lives, our identity and who we are, than the impacts.

We must expose the myths that underlie inaction around climate change and examine them in an objective way. Will it really ruin our economy to fix climate change? Will it take us back to the Stone Age? If we don’t tackle the myths directly, they will continue to thrive in our sub-conscious. For example, in Canada there is an idea that a carbon tax will destroy the economy. I like to point out that there were four provinces in Canada that had a price on carbon before it became a federal policy, and those four provinces have led the country in terms of economic growth and output.

Q: What part do you see IIASA playing in being able to build bridges between countries across political divides?

IIASA stands in a key position at a pivotal time. It is a truly international organization in terms of its mandate, structure, governance, and the people that work here. Climate change is a global problem and IIASA is a global institution that can offer both big-picture and regionally-specific insights into climate impacts and solutions.

Katharine Hayhoe visited IIASA on 4 October 2019 to give a lecture titled, Barriers to Public Acceptance of Climate Science, Impacts, and Solutions, to IIASA researchers and to meet with the IIASA Women in Science Club. IIASA has a worldwide network of collaborators who contribute to research by collecting, processing, and evaluating local and regional data that are integrated into IIASA models. The institute has 819 research partner institutions in member countries and works with research funders, academic institutions, policymakers, and individual researchers in national member organizations.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Nov 6, 2019 | Climate, Climate Change, Health, Young Scientists

By Luiza Toledo, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2019

2019 YSSP participant Rory Gibb discusses his work at IIASA developing models to understand the effects of future land use, climate, and socioeconomic change on disease risk, focusing on Lassa fever in West Africa as a case study.

© Seth Doyle | Unsplash

Climate change is a fact and one of the most important environmental changes that populations will face in the coming decades. Changes in areas such as agriculture, energy, economics, and biodiversity, together with other natural and human-made health stressors, influence human health and disease in numerous ways. This is evident in the fact that the emergence and spread of many infectious diseases is on the rise, many of them transmitted from wildlife to humans – a trend that has been associated with the environmental changes we are currently experiencing. Warmer average temperatures can mean longer warm seasons, earlier spring seasons, shorter and milder winters, and hotter summers, during which the prevailing conditions may affect the population cycles of hosts, vectors (such as mosquitoes and ticks) and pathogens, thus increasing the incidence of certain vector-borne or zoonotic diseases. Changes to land use, such as expansion of agriculture, can impact ecological communities and bring people into greater contact with wildlife, again potentially facilitating the spread of pathogens.

Rory Gibb, a 2019 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant, is doing research to understand how global environmental changes – and in particular interactions between land use and climate change – affect zoonotic (animal-borne) infectious diseases. He applied for the YSSP this summer because of the institute’s research portfolio in different dimensions of human wellbeing, including poverty and inequality, food security, and water resilience. He hopes to contribute a dimension about infectious diseases.

©Liebentritt_Christoph | IIASA

Gibb is interested in understanding how the same kind of environmental pressures that affect biodiversity and ecosystems, such as agricultural expansion, intensification and urbanization, may also impact human health. He points out that even though many infectious diseases are widely studied, such as dengue fever and malaria, we still have a patchy understanding of the environmental factors driving many more neglected or recently emerging diseases – as is the case with Lassa fever, which occurs only in West Africa.

Lassa fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic illness recognized by global health institutions as an important rodent-borne disease, however, many important aspects of the disease’s ecology, epidemiology, and distribution remain poorly understood.

“We know that the spread of Lassa fever is very dependent on the environment, so it is sensitive to climate change, land use change, and other ecological changes, but we don’t have a very clear understanding of where it occurs and how many people are being affected every year,” Gibb explains.

Gibb aims to use current knowledge of the local ecological processes that drive the disease, including spatial modeling to determine the extent of the disease’s rodent reservoir host and its interactions with people, to develop a better understanding of the number of people infected with Lassa fever in West Africa. His YSSP project is focused on understanding how sensitive current patterns of disease risk may be to plausible future agricultural, climatic, and economic change in the region. To do this, he is projecting disease risk over large geographical areas using remotely sensed data on climate and landscape factors, and evaluating the effects of future socio-environmental scenarios on the predicted incidence of human disease. Ultimately, he is interested in how to develop better models to understand the relationship between environmental change and diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites that spread between humans and animals. He hopes that his research outcomes can help to guide disease surveillance efforts for policymakers.

“The spatial modeling work that I am doing will hopefully be useful in terms of giving some insight into regions of West Africa that are predicted to have a very high risk for Lassa fever, both now and under expected environmental changes, to assist in targeting public health interventions such as improving diagnostic test access. We can also identify important knowledge gaps, such as areas that are highly environmentally suitable for Lassa transmission, but in which the disease is apparently absent – these may be useful locations for intensified surveillance, or for showing that there are other ecological or epidemiological processes occurring that we are not accounting for.”

The impacts that environmental changes have on our health remind us how dependent we are on nature and how our own health depends on that of the environment. Environmental and human health cannot and should not be seen as two separate things.

“I want to do work that highlights the importance of understanding human dependence on nature and the necessity of understanding how we can preserve the health of both ecosystems and people,” Gibb concludes.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.