Jun 18, 2018 | Alumni, Ecosystems, Environment, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Cecile Godde, PhD student at the University of Queensland, Australia and former IIASA YSSP participant

Cecile Godde ©Oli Sansom

Last year, I had the fantastic opportunity to spend three months at IIASA as part of the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), to collaborate with the Ecosystems Services and Management (ESM) research program. During this very enriching experience, both intellectually, socially, and culturally, I worked with Petr Havlik, David Leclère, and Christian Folberth on modeling global rangelands and pasturelands under farming and climate scenarios. I also progressed on the development of a global animal stocking rate optimizer. The overall objective of this YSSP project, and more broadly of my PhD, is to assess the role of grazing systems in a sustainable food system.

However, my trip to IIASA was not my only adventure last year. Just before moving to Vienna, I received the great news that I was selected along with 77 other women to take part in a women in science and leadership program called Homeward Bound.

What would our world look like if women and men were equally represented, respected, and valued at the leadership table? How might we manage our resources and our communities differently? How might we coordinate our response to global problems like food security and climate change?

Homeward Bound is a worldwide and world-class initiative that seeks to support and encourage women with scientific backgrounds into leadership roles, believing that diversity in leadership is key to addressing these complex and far-reaching issues. The program’s bold mission is to create a 1000-strong collective of women in science around the world over the next 10 years, with the enhanced leadership, strategic, and visibility capacity to influence policy and decision making for the benefit of the planet.

Antarctic penguins © Cecile Godde

This year-long program culminated in an intensive three-week training course in Antarctica, a journey from which I have just come back. The voyage to Antarctica was incredible. We learnt intensively during this 24/7 floating conference in the midst of majestic icebergs, very cute penguins, graceful whales, and extraordinary women from various cultures and backgrounds, from PhD students to Nobel Laureates. I have returned full of hope for the planet, deeply inspired, and emotionally energized. It was a truly unforgettable experience, one that will keep me reflecting for a lifetime.

Our days in Antarctica typically followed a similar routine – half of the day was dedicated to a landing (we visited Argentinian, Chinese, US, and UK research stations) and the other half to classes and workshops. We discussed systemic gender issues and learnt about leadership styles, peer-coaching, the art of providing feedback, science communication, core personal values, or what matter to us. The list goes on! We were also encouraged to practice reflective journaling. Regularly recording activities, situations, and thoughts on paper is actually a very powerful technique for self-discovery and personal and professional growth as it helps us think in a critical and analytical way about our behaviors, values, and emotions. We also spent quite some time developing our personal and professional strategies: What is our purpose as individuals? What are our core values, aspirations, and short- and long-term goals? From that, we developed a roadmap that could be executed as soon as we stepped off the ship. While I haven’t solved all my life’s mysteries, this activity gave me strong foundations to keep growing and actively shape my own life, rather than letting society do it for me.

In the evenings, we watched our film faculty sharing their tips with us on television, including primatologist Jane Goodall, world leading marine biologist Sylvia Earle, and former Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC), Christiana Figueres. We also had a collective art project called “Confluence: A Journey Homeward Bound”, which was underpinned by our inner journey of reflection, growth, and transformation and our outer physical journey to Antarctica.

Homeward Bound in Antarctica © Oli Sansom

Both my stay at IIASA and my journey to Antarctica taught me a lot about the value of getting out of my comfort zone, exploring different leadership styles, and collaborating. I have also witnessed how visibility (visibility to ourselves, to understand who we are, and visibility to others, to let the world know we exist) helps to open up opportunities. The good news is that the beliefs we have about ourselves are just that – beliefs – and these beliefs can be changed.

My visibility to others has also increased notably in relation to my involvement in Homeward Bound and my recent award of the Queensland Women in STEM prize. This Australian annual prize, awarded by the Minister for Environment and Science, Leeanne Enoch and Acting Chief Scientist Dr Christine Williams, aims to celebrate the achievements of women who are making a difference in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. As a result, I have been contacted by fascinating people from various fields of work, from researchers and teachers to entrepreneurs, start-ups, and industries. All these connections have broadened my approach to food security and global change and helped me shape my research vision, purpose, and values.

When we were in Antarctica, our story reached 750 million people. Why? Because, and may we never forget, the world believes in us – ‘us’ in its broadest sense: humans, scientists, women, etc. – in our skill, compassion, and capability. While we are facing alarming global social, economic, and environmental challenges, I believe that the many collaborations that embrace diversity of knowledge, skills, processes, and leadership styles that are currently emerging all around the world, will help us get closer to our development goals.

Homeward Bound is a 10-year long initiative. Find out more about the program and how to apply here: http://homewardboundprojects.com.au

Follow my journey: –

May 28, 2018 | Air Pollution, Climate, Climate Change, Ecosystems, Energy & Climate, Women in Science

By Beatriz Mayor, Research Scholar at IIASA

On 14 and 15 May, Vienna hosted two important events within the frame of the world energy and climate change agendas: the Vienna Energy Forum and the R20 Austrian World Summit. Since I had the pleasure and privilege to attend both, I would like to share some insights and relevant messages I took home with me.

Beatriz Mayor at the Austrian World Summit © Beatriz Mayor

To begin with, ‘renewable energy’ was the buzzword of the moment. Renewable energy is not only the future, it is the present. Recently, 20-year solar PV contracts were signed for US$0.02/kWh. However, renewable energy is not only about mitigating the effects of climate change, but also about turning the planet into a world we (humans from all regions, regardless of the local conditions) want to live in. It is not only about producing energy, about reaching a number of KWh equivalent to the expected demand–renewables are about providing a service to communities, meeting their needs, and improving their ways of life. It does not consist only of taking a solar LED lamp to a remote rural house in India or Africa. It is about first understanding the problem and then seeking the right solution. Such a light will be of no use if a mother has to spend the whole day walking 10 km to find water at the closest spring or well, and come back by sunset to work on her loom, only to find that the lamp has run out of battery. Why? Because her son had to take it to school to light his way back home.

This is where the concept of ‘nexus’ entered the room, and I have to say that more than once it was brought up by IIASA Deputy Director General Nebojsa Nakicenovic. A nexus approach means adopting an integrated approach and understanding both the problems and the solutions, the cross and rebound effects, and the synergies; and it is on the latter that we should focus our efforts to maximize the effect with minimal effort. Looking at the nexus involves addressing the interdependencies between the water, energy, and food sectors, but also expanding the reach to other critical dimensions such as health, poverty, education, and gender. Overall, this means pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

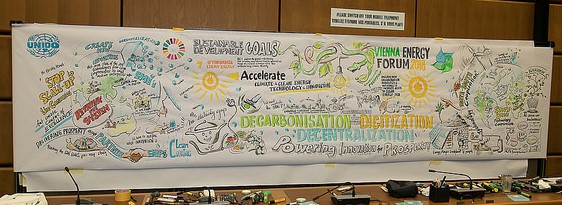

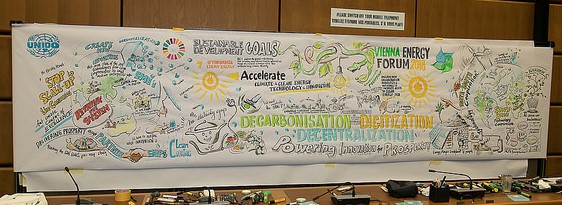

Vienna Energy Forum banner created by artists on the day © UNIDO / Flickr

Another key word that was repeatedly mentioned was finance. The question was how to raise and mobilize funds for the implementation of the required solutions and initiatives. The answer: blended funding and private funding mobilization. This means combining different funding sources, including crowd funding and citizen-social funding initiatives, and engaging the private sector by reducing the risk for investors. A wonderful example was presented by the city of Vienna, where a solar power plant was completely funded (and thus owned) by Viennese citizens through the purchase of shares.

This connects with the last message: the importance of a bottom-up approach and the critical role of those at the local level. Speakers and panelists gave several examples of successful initiatives in Mali, India, Vienna, and California. Most of the debates focused on how to search for solutions and facilitate access to funding and implementation in the Global South. However, two things became clear. Firstly, massive political and investment efforts are required in emerging countries to set up the infrastructural and social environment (including capacity building) to achieve the SDGs. Secondly, the effort and cost of dismantling a well-rooted technological and infrastructural system once put in place, such as fossil fuel-based power networks in the case of developed countries, are also huge. Hence, the importance of emerging economies going directly for sustainable solutions, which will pay off in the future in all possible aspects. HRH Princess Abze Djigma from Burkina Faso emphasized that this is already happening in Africa. Progress is being made at a critical rate, triggered by local initiatives that will displace the age of huge, donor-funded, top-down projects, to give way to bottom-up, collaborative co-funding and co-development.

Overall, if I had to pick just one message among the information overload I faced over these two days, it would be the statement by a young fellow in the audience from African Champions: “Africa is not underdeveloped, it is waiting and watching not to repeat the mistakes made by the rest of the world.” We should keep this message in mind.

May 2, 2018 | Alumni, Economics, IIASA Network, Science and Policy

W. Brian Arthur from the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), and a former IIASA researcher, talks about increasing returns and the magic formula to get really great science.

Recently, Brian stopped in at the Complexity Science Hub Vienna, of which IIASA is a member institution, and spoke to Verena Ahne about his work.

Brian Arthur (© Complexity Science Hub)

Brian, now 71, is one of the most influential early thinkers of the SFI, a place that without exaggeration could be called the cradle of complexity science.

Brian became famous with his theory of increasing returns. An idea that has been developed in Vienna, by the way, where Brian was part of a theoretical group at the IIASA in the early days of his career: from 1978 to 1982.

“I was very lucky,” he recalls. “I was allowed to work on what I wanted, so I worked on increasing returns.”

The paper he wrote at that time introduced the concept of positive feedbacks into economy.

The concept of “increasing returns”

Increasing returns are the tendency for that which is ahead to get further ahead, for that which loses advantage to lose further advantage. They are mechanisms of positive feedback that operate—within markets, businesses, and industries—to reinforce that which gains success or aggravate that which suffers loss. Increasing returns generate not equilibrium but instability: If a product or a company or a technology—one of many competing in a market—gets ahead by chance or clever strategy, increasing returns can magnify this advantage, and the product or company or technology can go on to lock in the market.”

(W Brian Arthur, Harvard Business Review 1996)

This was a slap in the face of orthodox theories which saw–and some still see–economy in a state of equilibrium. “Kind of like a spiders web,” Brian explains me in our short conversation last Friday, “each part of the economy holding the others in an equalization of forces.”

The answer to heresy in science is that it does not get published. Brian’s article was turned down for six years. Today it counts more than 10.000 citations.

At the latest it was the development and triumphant advance of Silicon Valley’s tech firms that proved the concept true. “In fact, that’s now the way how Silicon Valley runs,” Brian says.

The youngest man on a Stanford chair

William Brian Arthur is Irish. He was born and raised in Belfast and first studied in England. But soon he moved to the US. After the PhD and his five years in Vienna he returned to California where he became the youngest chair holder in Stanford with 37 years.

Five years later he changed again – to Santa Fe, to an institute that had been set up around 1983 but had been quite quiet so far.

Q: From one of the most prestigious universities in the world to an unknown little place in the desert. Why did you do that?

A: In 1987 Kenneth Arrow, an economics Nobel Prize winner and mentor of mine, said to me at Stanford: We’re holding a small conference in September in a place in the Rockies, in Santa Fe, would you go?

When a Nobel Prize winner asks you such a question, you say yes of course. So I went to Santa Fe.

We were about ten scientists and ten economists at that conference, all chosen by Nobel Prize winners. We talked about the economy as an evolving complex system.

Veni, vidi, vici

Brian came – and stayed: The unorthodox ideas discussed at the meeting and the “wild” and free atmosphere of thinking at “the Institute”, as he calls the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), thrilled him right away.

In 1988 Brian dared to leave Stanford and started to set up the first research program at Santa Fe. Subject was the economy treated as a complex system.

Q: What was so special about SF?

A: The idea of complexity was quite new at that time. But people began to see certain patterns in all sorts of fields, whether it was chemistry or the economy or parts of physics, that interacting elements would together create these patterns…To investigate this in universities with their particular disciplines, with their fixed theories, fixed orthodoxies–where it is all fixed how to do things–turned out to be difficult.

Take the economy for example. Until then people thought it was in an equilibrium. And there we came and proved, no, economics is no equilibrium! The Stanford department would immediately say: You can’t do that! Don’t do that! Or they would consider you to be very eccentric…

So a bunch of senior fellows at Los Alamos in the 1980s thought it would be a good idea if there was an independent institute to research these common questions that came to be called complexity.

At Santa Fe you could talk about any science and any basic assumptions you wanted without anybody saying you couldn’t or shouldn’t do that.

Our group as the first there set a lot of this wild style of research. There were lots of discussions, lots of open questions, without particular disciplines… In the beginning there were no students, there was no teaching. It was all very free.

This wild style became more or less the pattern that has been followed ever since. I think the Hub is following this model too.

The magic formula for excellence

Q: Was this just a lucky concurrence: the right people and atmosphere at the right time? Or is there a pattern behind it that possibly could be repeated?

A: I am sure: If you want to do interdisciplinary science – which complexity is: It is a different way of looking at things! – you need an atmosphere where people aren’t reinforced into all the assumptions of the different disciplines.

This freedom is crucial to excellent science altogether. It worked out not only for Santa Fe. Take the Rand Corporation for instance, that invented a lot of things including the architecture of the internet, or the Bell Labs in the Fifties that invented the transistor. The Cavendish Lab in Cambridge is another one, with the DNA or nuclear astronomy…

The magic formula seems to be this:

- First get some first rate people. It must be absolutely top-notch people, maybe ten or twenty of them.

- Make sure they interact a lot.

- Allow them to do what they want – be confident that they will do something important.

- And then when you protect them and see that they are well funded, you are off and running.

Probably in seven cases out of ten that will not produce much. But quite a few times you will get something spectacular – game changing things like quantum theory or the internet.

Don’t choose programs, choose people

Q: This does not seem to be the way officials are funding science…

A: Yes, in many places you have officials telling people what they need to research. Or where people insist on performance and indices… especially in Europe, I have the impression, you have a tradition of funding science by insisting on all these things like indices and performance and publications or citation numbers. But that’s not a very good formula.

Excellence is not measurable by performance indicators. In fact that’s the opposite of doing science.

I notice at places where everybody emphasize all this they are not on the forefront. Maybe it works for standard science; and to get out the really bad science. But it doesn’t work if you want to push boundaries.

Many officials don’t understand that.

In Singapore the authorities once asked me: How did you decide on the research projects in Santa Fe? I said, I didn’t decide on the research projects. They repeated their question. I said again, I did not decide on the research projects. I only decided on people. I got absolutely first rate people, we discussed vaguely the direction we wanted things to be in, and they decided on their research projects.

That answer did not compute with them. They are the civil service, they are extraordinarily bright, they’ve got a lot of money. So they think they should decide what needs to be researched.

I should have told them – I regret I didn’t: This is fine if you want to find solutions for certain things, like getting the traffic running or fixing the health care system. Surely with taxpayer’s money you have to figure such things out. But you will never get great science with that. All you get is mediocrity.

Of course now they asked, how do we decide which people should be funded? And I said: “You don’t! Just allow top people to bring in top people. Give them funding and the task of being daring.”

Any other way of managing top science doesn’t seem to work.

I think the Hub could be such a place – all the ingredients are here. Just make sure to attract some more absolutely first rate people. If they are well funded the Hub will put itself on the map very quickly.

This interview was originally published on https://www.csh.ac.at/brian-arthurs-magic-formula-for-excellence/

Mar 15, 2018 | Poverty & Equity, Women in Science

Monika Bauer, IIASA Alumni Officer

International Women’s Day is celebrated worldwide every year on 8 March. The event aims to promote the work and rights of women. This year, IIASA celebrated International Women’s Day with a panel discussion which asked the question, “Can a women-empowered world resolve some of the global sustainability challenges?” IIASA Population Researcher Raya Muttarak, moderated the panel that included Tyseer Aboulnasr, Melody Mentz, Shonali Pachauri, and Mary Scholes.

“The IIASA Women in Science Club chose this topic because it would allow the panelists to reflect on the potential welfare benefits of a more gender-balanced world. We wanted to know if balance could benefit both women and men, and we wanted to provide a space to discuss the potential intersectionality of the challenges to female empowerment such as poverty, racism, sexism, access to education, health autonomy, and resource inequality,” said organizer Amanda Palazzo, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management researcher.

IIASA Director General and CEO Professor Dr. Pavel Kabat opened the discussion by offering a brief history of International Women’s Day in the context of the early history of IIASA.

Melody Mentz gives her thoughts

Mentz, an independent higher education research and evaluation consultant based in South Africa, spoke about the implications that a gender-balanced world could hold for science and sustainability using the African agricultural system as an example. To this end, she presented a few statistics that show how the African food system intersects with the sustainable development goal of gender equality.

According to the most recent Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations study, women do up to 50 % of agricultural labor in Africa (this varies by country). Bearing this fact in mind, women however, own only 10 % of the land in Africa; they receive less than 10% of the investments in agriculture on the continent; and less than 5% of women have access to advisory services. In addition, they hold just 14% of management positions in the sector, and only one in four agricultural researchers on the continent is female.

“There is a huge disparity between the contributions of women, the impact of the current food system on women, and the role that the environment allows them to play,” explained Mentz.

As far as the implications of this are concerned, the first, and perhaps the most obvious, is that we need more women in science. Secondly, according to Mentz, we also need more science for women.

“At an institutional level we [should] start thinking differently about what kind of questions we answer. Those questions don’t have to be focused on women, but rather, should consider the implications for both men and women,” she said.

Thirdly, she argued for more science with women, as many research questions and research designs are not just driven by scientists, but actually originate with the people that researchers are trying to help. Finally, we also need more science about women, meaning that data and indicators of impact need to include gender, especially in the context of Africa.

IIASA Energy Researcher Pachauri reflected on the inequalities that we see in our everyday lives. Her work specializes in household energy access in the developing world. Pachauri shared an example from an organization called ENERGIA, of which she is a member of the advisory board, where women were included as microentrepreneurs in the delivery of energy in villages. The organization found that female entrepreneurs were more successful and profitable than the men, which they put down to a greater use of social networks and relationships. The example demonstrated how societies can benefit from including women in solutions for everyday problems.

Aboulnasr, a retired electrical engineering professor, focused on the importance of balance – whether it is a balance of genders, social classes, or geography. Aboulnasr eloquently suggested that rather than striving for perfect balance, one should accept a more dynamic and changing balance. She also stated that one should focus on the impact, rather than on the tools. For example, excellent science is a tool for reaching a goal that makes an impact, rather than excellence in science being the goal. Her advice to the audience was to be open to accepting failure in one’s life.

“If you don’t fail in 30% of what you attempt to do, then you have never reached your limits,” she said, and encouraged the audience to stop obsessing about the failures of the past, seek balance, and to not feel guilty.

Scholes, a professor at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa, approached the question of the day differently. She urged the audience to look at the question from a sustainability perspective, and to ask what role gender has to play in stewardship for the planet. In addition, she asked the audience to consider whether our unstainable use of resources is because of gender inequality, or because of a more underlying misalignment of values, and what type of empowerment might be needed to achieve a more sustainable world.

“As far as we know, this is the first panel discussion hosted at IIASA which has specifically tried to examine the role of women in achieving a sustainable future. We learned that there are pockets of IIASA research already exploring this this issue and that there is room and interest to engage in this discussion in the future,” says Palazzo.

It is clear that there is no simple answer to the issues surrounding the topic of our International Women’s Day panel discussion. The event however, highlighted unique reflections and experiences from each panelist, and the IIASA Women in Science Club will continue to explore and push the discussion forward. We look forward to updating you soon.

Some of of the panel discussion attendees wearing red, purple and black themed clothes for International Women’s Day

Mar 7, 2018 | Energy & Climate

By Jessica Jewell, David McCollum, Johannes Emmerling, Christoph Bertram, David E.H.J. Gernaat, Volker Krey, Leonidas Paroussos, Loïc Berger, Kostas Fragkiadakis, Ilkka Keppo, Nawfal Saadi, Massimo Tavoni, Detlef van Vuuren, Vadim Vinichenko, Keywan Riahi

Our recent paper about our research on the effects of removing fossil fuel subsidies, published in Nature on February 8, 2018, generated a lot of comment and debate.

Here, we respond to three important themes raised in these comments. The first concerns the interpretation of our findings about the significance of subsidy removal for reducing CO2 emissions, the second concerns our approach to modeling and the data we used, and the third relates to policy options for more effective subsidy reform.

© Shutterstock / huyangshu

What are fossil fuel subsidies and why are they interesting for climate?

Fossil fuel subsidies are government interventions which decrease the price of fossil fuels below the market price. They can go to supporting the extraction of oil, gas, and coal (production subsidies) or making fuels cheaper for consumers (consumption subsidies) and amounted to over US$400 billion in 2015. There is a certain irony in that so many governments signed on to the Paris Agreement in 2015 yet in that same year many of those same governments spent so much money making fossil fuels cheaper.

How much would removing these subsidies help climate change mitigation efforts? How does it compare to what countries have already pledged to do for the climate under the Paris Agreement?

Comparing emission reductions from subsidy removal to key climate targets

Some commenters claim that it is already known that the effect of removing fossil fuel subsidies on emissions is limited. However, according to the authoritative Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC AR5), subsidy reform “can achieve significant emission reductions”. This view also is evident in the political sphere as: the Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform, a group of countries called fossil fuel subsidy reform “the missing piece of the puzzle in the fight against climate change”.

Our findings are that fossil fuel subsidy removal would lead to a 1-4% reduction in CO2 emissions in the energy sector by 2030 if oil prices stay low, and 1-5% if oil prices rise again, compared to the rise in emissions if subsidies are maintained, the baseline. It means that subsidy reform is a modest contribution to the global reductions required to achieve 2°C in a least-cost pathway, 27-57% by 2030.

More importantly, in our paper we compare emission reductions from subsidy removal not to this ideal goal, but to the actual targets pledged in the context of the Paris Agreement. Globally, Paris pledges would reduce emissions against the baseline in the energy sector by 9-13% in 2030 (under a moderate growth baseline) which is a larger reduction than fossil fuel subsidy removal would deliver. Under both the Paris climate pledges and fossil fuel subsidy phase-out global emissions would continue to rise whereas to achieve the 2°C target they should peak and eventually decline.

Identifying the regions with greatest impact

This global assessment is only part of our study. In addition, we show how the impacts of subsidy removal are different by region. In the major oil and gas exporting regions (Middle East and North Africa, Russia and its neighboring countries, and Latin America), removing fossil fuel subsidies lowers emissions by the same amount or more than these countries’ Paris pledges. Government revenues in these regions largely come from energy exports, which are squeezed by today’s low oil prices. Lowering government spending by removing subsidies is a real political opportunity to reduce emissions in these regions.

In other developing and emerging economies (India, China, the rest of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa), removing fossil fuel subsidies has less of an effect on emissions than these countries’ Paris pledges. In addition, the number of people who might be affected by subsidy removal in these regions is higher, simply because there are many more people living below the poverty line, for whom subsidies make the most difference. Taken together, these two findings frame one of our main results: that subsidy removal would be most useful for the climate precisely in the regions where it would affect fewer people living below the poverty line.

Data on subsidies

The second theme we would like to address relates to our data and modeling. Some commenters claimed that we underestimate both production subsidies and the effect of their removal.

According to data from the IEA and OECD only about 4% of subsidies are production subsidies. The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and Overseas Development Institute (ODI) publish an independent estimate based on their own definition and approach. Extrapolating to the global level, production subsidies would be about 14% in 2013 under their approach. We ran a sensitivity analysis using this higher production subsidies estimate. This did not change our findings (discussed in the Supplementary Information to our article).

Some commenters claimed that our study does not consider electricity production subsidies. This is also not true. We use the IEA data where power generation subsidies are captured in electricity subsidies. The SI discusses how each model integrates electricity subsidies.

There are other, fragmented estimates for electricity generation subsidies in individual countries, which generally take a different view of subsidies. For example, the recent report from IISD on Chinese subsidies to coal-fired power plants indicates that in 2014 and 2015, between 89% and 97% of these subsidies went to incentivize air pollution control equipment or closing inefficient plants. According to the same report, these subsidies also dropped by half from 2014 to 2015. Few governments would consider this as an environmentally-harmful subsidy, and removing such support will increase, not decrease emissions.

For our main analysis, we relied on IEA and OECD data for both production and consumption subsidies because these inventories are aligned with governments’ own estimates which are prepared as part of the G20 pledge to remove subsidies from 2009 reaffirmed in 2016. By using the same input data as governments and international organizations who are pledging or considering fossil fuel subsidy removal, we ensure the policy relevance of our results for these actors.

Estimating the effects of production subsidy removal

There were several comparisons of our results with those reported in a recent paper by Erickson et.al. in Nature Energy, which found that under the currently low oil prices, removing production subsidies in the US would make several oil fields unprofitable and eventually result in their closure. We find contrasting these two papers misleading as they ask very different research questions. Our study does not investigate how many oil fields in the US or elsewhere will become unprofitable after subsidy removal, but looks at the global effect of subsidy removal on emissions by taking into account trade in fossil fuels, the demand response and potential substitution of fuels and technologies. Erickson and his colleagues do not ask how much emissions will change as a result of closed oil fields. These are two very different questions.

Erickson and his colleagues compare the amount of carbon embedded in the oil reserves that may become unprofitable due to subsidy removal, to how much carbon the US would be allowed to emit under a stringent climate target. This creates an impression that they investigate the impact of removing oil production subsidies on US emissions. However, calculating the emission impact from removing oil production subsidies requires not only calculating the emissions embedded in foregone oil production, but also the possible emissions resulting from replacing this lost oil with other fuels, or changes in demand, for example if Americans choose to drive less if wells are closed, or if the US imports oil instead. We use these types of feedbacks in our models to calculate the emissions effects of subsidy removal (both consumption and production).

Redirecting subsidy funds

The third theme raised in the comments to our article was why we did not model redirecting subsidies to supporting renewable energy. While this is a very tempting question to ask from a climate perspective, and certainly one which we could do in our models, we did not consider it a realistic policy to be prioritized in our scenarios. In most countries fuel subsidies were introduced to support those on low incomes, although it is an inefficient way to do so. A state budget deficit and today’s low oil prices can often prompt successful subsidy reform. Indonesia for example recently expanded spending on infrastructure and programs to reduce poverty, while India introduced vouchers for cooking fuels. Iran, meanwhile introduced universal health coverage.

Fossil fuel subsidies do need reform

We would like to express our agreement with two comments, one from Ian Parry who wrote a commentary to our paper in Nature, and another from David Victor in his statement to Scientific American, that there are many reasons to reform fossil fuel subsidies other than emissions reductions. Our article does not cover these reasons and should not be interpreted as a comprehensive assessment of all aspects of subsidy removal.

We do however hope that our transparent and rigorous assessment of the effects of subsidy removal on CO2 emissions and energy use will support realistic and effective subsidy removal policies, and help in understanding the relative importance of a range of emission-reduction measures needed for achieving the ambitious long-term targets of the Paris Agreement.

As some commenters pointed out, we need all tools in the box to combat the enormous challenge of climate change. We fully agree. At the same time, we also believe in the need to understand how much each tool can do and where it can be most effective. This is exactly what our study answers.

Reference

Jewell J, McCollum, D Emmerling J, Bertram C, Gernaat DEHJ, Krey V, Paroussos L, Berger L, Fragkiadakis K, Keppo I, Saadi, N, Tavoni M, van Vuuren D, Vinichenko V, Riahi K (2018) Limited emission reductions from fuel subsidy removal except in energy exporting regions. Nature DOI: 10.1038/nature25467

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.