Apr 15, 2020 | Austria, COVID19, Demography

By Erich Striessnig, researcher in the IIASA World Population Program

Erich Striessnig discusses the risks posed by the current COVID-19 pandemic and shares insights from his latest research around socioeconomic indicators related to the pandemic in Austria.

© Bennymarty | Dreamstime.com

Late last year, my IIASA colleague Raya Muttarak, Roman Hoffmann from the Vienna Institute of Demography/Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, and I were informed by the City of Vienna that our proposal to study “Climate, Health and Population” (CHAP) in the metropolitan area of Vienna had been granted funding for the 2020 period. Originally, we wanted to study what climate change and demographic change in the rapidly growing Austrian capital implies with regard to future vulnerability to extreme weather events. As the city is booming with economic activity and experiencing more tropical summer heat every year, the extent of the urban heat island increases as well, thus posing a steadily increasing risk to the city’s growing population, especially the elderly.

One conventional way of thinking about a population’s risk in the context of climate change is to decompose the risk and focus on its individual components. According to the famous “risk triangle” after Crichton, risk equals hazard times exposure times vulnerability. If any of the three can be taken out of the equation, the risk is reduced to zero … much like in the absence of sun, even the palest person can safely go outside without sunscreen! If, however, the hazard is there, people would be well advised to either not expose themselves to the sun or to reduce their vulnerability to skin damage and cancer by wearing sunscreen.

Now what does that have to do with our current predicament of a vast fraction of the world’s population being quarantined due to the outbreak of COVID-19? Well, as we and our CHAP colleagues were waiting for the meteorological data necessary for answering CHAP’s main research questions, we thought that we could focus on this much more imminent threat instead. In some way, the risk posed by COVID-19 can be viewed under the same lens as the above risk equation:

In terms of hazard, COVID-19 represents an unprecedented shock to social and economic systems and thus has a lot in common with climate-induced natural disasters. As humans are the carriers of the disease, the number of infected people in a local area can be considered as the hazard estimate. Meanwhile, by employing physical distancing (while remaining socially very active and helping, in particular, those around us that are in a more dire situation), we can lower exposure to that hazard a great deal and the risk can be reduced decisively. While under a business-as-usual scenario, our health system would soon find itself overwhelmed by an unbearable demand for health care, eventually having to give up lots of patients. The quarantine measures imposed in many countries serve to lower exposure and subsequently “flatten the curve”. So in order to reduce your own risk exposure and avoid increasing the risk for others, everyone who can afford to, please stay at home!

Likewise, we can to a certain extent work on lowering our vulnerability, both at the individual and at the societal level. Not everyone is equally vulnerable to the disease. As in the case of facing the challenges of climate change, populations faced with this pandemic are characterized by demographic differential vulnerability, expressed by the fact that the virus is more (but certainly not exclusively) lethal for older people, as well as those with preexisting health conditions and weakened immune systems. To reduce our individual vulnerability (in case we are exposed to the hazard), we can work on strengthening our immune systems.

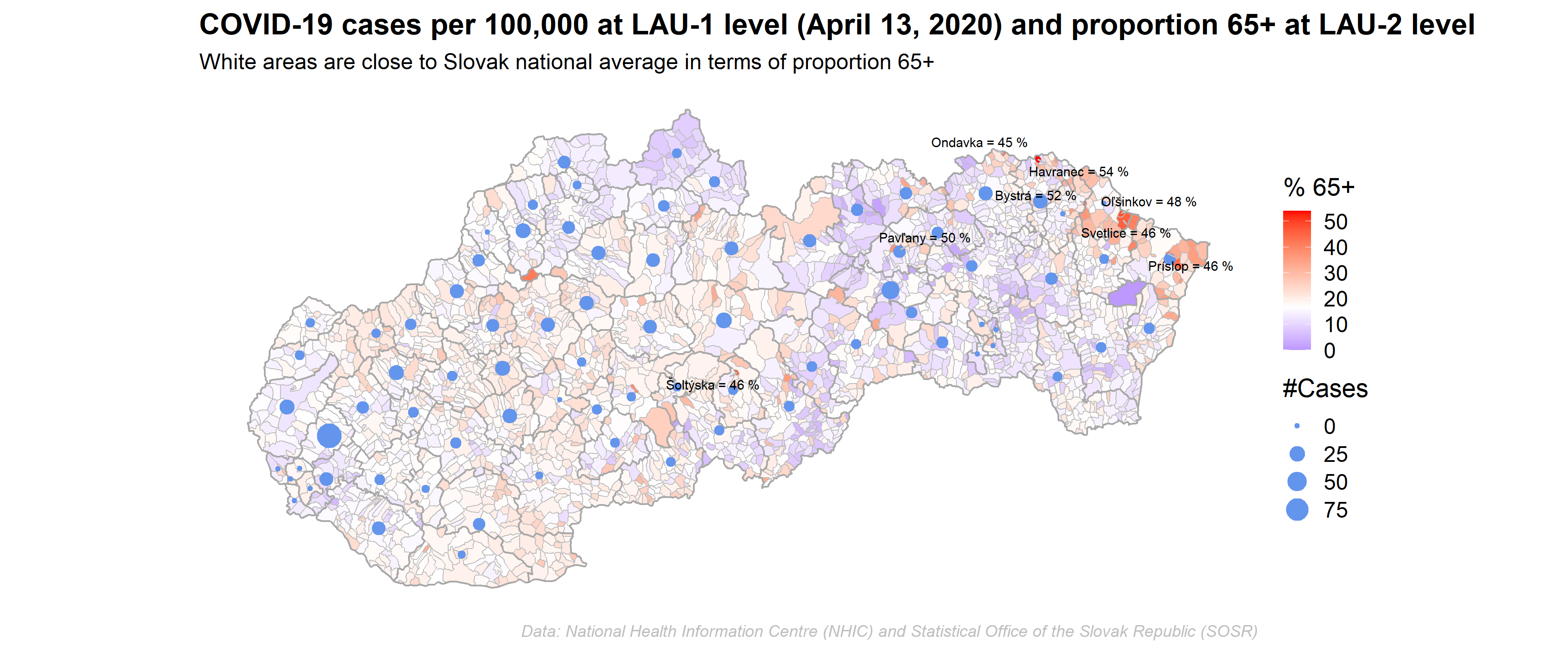

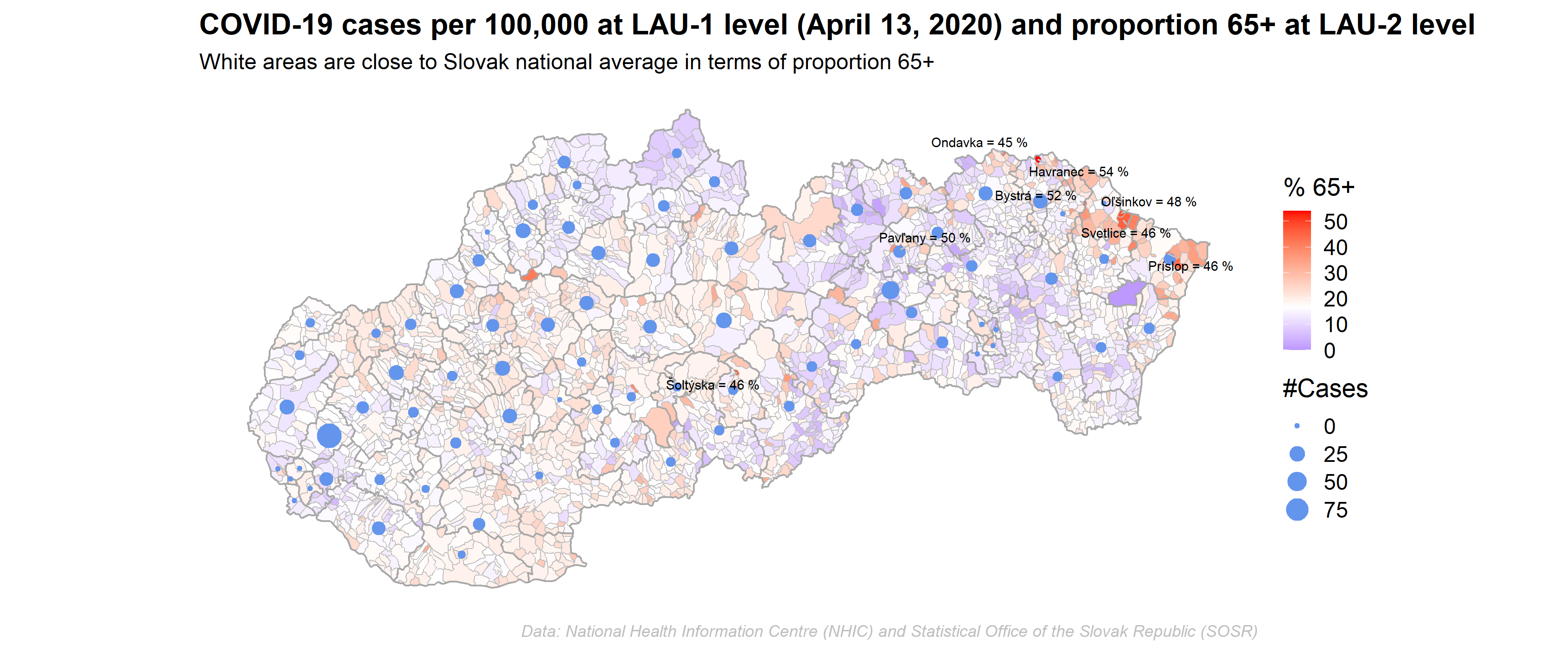

At the societal level, we can reduce risks by identifying those places where the disease outbreak might have the strongest impact. For this we need suitable indicators available with sufficient spatial granularity. The initial, pre-lockdown infection hotspots, were often places that are well connected, such as travel hubs and touristic areas. In some cases, though, these hotspots were created simply as the consequence of bad luck, in other words, because there was a local “super-spreader” or a social event that brought together a large number of people. Such situations can hardly be anticipated. What we might be able to anticipate, though, are those vulnerable geographical hotspots where, given the pre-existing burden of disease, as well as the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the people that live there, the pandemic might cause the most havoc.

In line with the work by our IIASA colleague, Asjad Naqvi, we set out to map various indicators at the Austrian and Slovak municipal level (Slovak data courtesy of Michaela Potancokova from the IIASA World Population Program). Our indicators include things like the proportion of elderly population (>70+) or population density, but also the proportion of people with low socioeconomic status or a region’s connectedness in terms of the proportion of population commuting for work. These indicators can have varying importance in the short, medium, and long term — while mobility is no longer a big issue now that the population is in lockdown, socioeconomic characteristics, for example, may play a bigger role the longer the crisis lasts. While at the initial stages, Austrians with higher socioeconomic status were more likely to get infected due their mobility and larger social networks, the socioeconomic gradient might turn around eventually and those with lower social status might carry the brunt of the pandemic, as they are more likely to become unemployed and stay there for a longer period of time.

Our work to create a meaningful risk index from such vulnerability indicators is still in progress, but we aspire to pinpoint which areas are most likely going to need additional interventions, such as more testing or increased hospital capacities. This exercise will not only be useful at later stages of the pandemic, that is, when we slowly start moving back from the current quarantine situation (“The Hammer”) to gradual normalization (“The Dance”), but also when faced by other types of risks, such as from climatic hazards or economic shocks.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Jan 29, 2020 | Demography, Health, Wellbeing

By Sonja Spitzer, research assistant in the IIASA World Population Program

Sonja Spitzer discusses how survey data often fails to capture all socioeconomic groups and explains how to ensure health information used by policymakers is based on accurate statistics.

Life expectancy continues to increase in Europe. We live longer, but do we live healthier? One way of tackling this question is by analysing health expectancy: a widely used indicator that counts the number of years an average person can expect to live in good health. To create this indicator researchers usually combine information about mortality with health data from surveys – and this is where many problems begin.

Survey participation is shaped by socioeconomic differences

Surveys do not always correctly represent the countries they seek to describe. A common deviation is that highly educated individuals are more likely to participate in surveys than less-educated individuals This is problematic for health research in particular, because highly educated people tend to be healthier than those who are less educated. Overrepresenting healthy and better educated individuals in surveys makes countries appear to have healthier populations than is the actual case. A recent study I conducted, that focused on European countries, showed that health expectancy measures are frequently upward biased, because less-educated people are underrepresented in the underlying data. The results of this study reflect the outcomes of other research; for example, estimates of rates of diabetes and asthma in Belgium are too low because individuals with a high level of education are overrepresented in the core data. In the Netherlands, the underrepresentation of those with lower levels of education has led to underestimating smoking prevalence, alcohol intake, and low levels of physical activity.

Make everyone count with statistical weights

Are you now wondering if you can ever trust health measures again? Do not despair! Surveys can still be a very useful source for answering health-related questions if the appropriate statistical tools are used. It is possible to account for the misrepresentation of participants with lower levels of education in surveys. The only thing needed is accurate information about the education structure of the population, that is: How many highly educated versus less-educated individuals live in a given country? In Europe, this information is readily available via censuses. Using information from censuses makes it possible to calculate statistical weights for surveys. If the less educated are underrepresented in surveys, each observation of a less educated individual is weighted relatively more than those with a higher level of education to account for the misrepresentation. This weighting enables surveys to resemble the population in the real world and the health measures that are based on them to no longer be biased by educational differences in survey participation.

Why do the less educated not participate in surveys?

Using survey methods such as statistical weights might become even more necessary in the future – it appears that the gap in survey participation between the higher and the less-educated is increasing year upon year. Those with low levels of education are frequently more difficult to engage, for example, less educated people can have less stable life paths and thus more often change their address. They may be less likely to provide requested information in surveys because they are too sick to participate or are less aware of the details of their health and financial situation. Finally, survey participation is usually voluntary and those with lower levels of education are more likely to refuse participation. One could speculate that this refusal to participate is because we, as researchers fail to engage with, or reach out to, less-educated individuals and the “value” of participating in surveys is therefore not well-communicated. This concern seems particularly important in the age of ‘fake news’. If less-educated individuals were better represented in surveys, this would make official statistics more reliable and might also lead to a better appreciation of statistics and how they can be more profound indicators than, for example, an opinion posed by someone on TV.

References:

[1] Demarest, S., Van Der Heyden, J., Charafeddine, R., Tafforeau, J., Van Oyen, H., Van Hal, G.: Socio economic differences in participation of households in a Belgian national health survey. European Journal of Public Health. 23, 981–985 (2013). DOI:10.1093/eurpub/cks158

[2] Korkeila, K., Suominen, S., Ahvenainen, J., Ojanlatva, A., Helenius, H.: Non-response and related factors in a nation-wide health survey. European Journal of Epidemiology 17, 991–999 (2001)

[3] Reinikainen, J., Tolonen, H., Borodulin, K., Härkänen, T., Jousilahti, P., Karvanen, J., Koskinen, S., Kuulasmaa, K., Männistö, S., Rissanen, H., Vartiainen, E.: Participation rates by educational levels have diverged during 25 years in Finnish health examination surveys. European Journal of Public Health. 28, 237–243 (2018). DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckx151

[4] Spitzer, S., Biases in health expectancies due to educational differences in survey participation of older Europeans: It’s worth weighting for. The European Journal of Health Economics. (2020) IIASA doi:10.1007/s10198-019-01152-0. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/16281/

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 29, 2019 | Science and Policy, Vietnam

Tran Thi Vo-Quyen, IIASA guest research scholar from the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (VAST), talks to Professor Dr. Ninh Khac Ban, Director General of the International Cooperation Department at VAST and IIASA council member for Vietnam, about achievements and challenges that Vietnam has faced in the last 5 years, and how IIASA research will help Vietnam and VAST in the future.

Professor Dr. Ninh Khac Ban, Director General of the International Cooperation Department at VAST and IIASA council member for Vietnam

What have been the highlights of Vietnam-IIASA membership until now?

In 2017, IIASA and VAST researchers started working on a joint project to support air pollution management in the Hanoi region which ultimately led to the successful development of the IIASA Greenhouse Gas – Air Pollution Interactions and Synergies (GAINS) model for the Hanoi region. The success of the project will contribute to a system for forecasting the changing trend of air pollution and will help local policy makers develop cost effective policy and management plans for improving air quality, in particular, in Hanoi and more widely in Vietnam.

IIASA capacity building programs have also been successful for Vietnam, with a participant of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) becoming a key coordinator of the GAINS project. VAST has also benefited from two members of its International Cooperation Department visiting the IIASA External Relations Department for a period of 3 months in 2018 and 2019, to learn about how IIASA deals with its National Member Organizations (NMOs) and to assist IIASA in developing its activities with Vietnam.

What do you think will be the key scientific challenges to face Vietnam in the next few years? And how do you envision IIASA helping Vietnam to tackle these?

In the global context Vietnam is facing many challenges relating to climate change, energy issues and environmental pollution, which will continue in the coming years. IIASA can help key members of Vietnam’s scientific community to build specific scenarios, access in-depth knowledge and obtain global data that will help them advise Vietnamese government officials on how best they can overcome the negative impact of these issues.

As Director General of the International Cooperation Department, can you explain your role in VAST and as representative to IIASA in a little more detail?

In leading the International Cooperation Department at VAST, I coordinate all collaborative science and technology activities between VAST and more than 50 international partner institutions that collaborate with VAST.

As the IIASA council representative for Vietnam, I participate in the biannual meeting for the IIASA council, I was also a member of the recent task force developed to implement the recommendations of a recent independent review of the institute. I was involved in consulting on the future strategies, organizational structure, NMO value proposition and need to improve the management system of IIASA.

In Vietnam, I advised on the establishment of a Vietnam network for joining IIASA and I implement IIASA-Vietnam activities, coordinating with other IIASA NMOs to ensure Vietnam is well represented in their countries.

You mentioned the development of the Vietnam-IIASA GAINS Model. Can you explain why this was so important to Vietnam and how it is helping to improve air quality and shape Vietnamese policy around air pollution?

Air pollution levels in Vietnam in the last years has had an adverse effect on public health and has caused significant environmental degradation, including greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, undermining the potential for sustainable socioeconomic development of the country and impacting the poor. It was important for Vietnam to use IIASA researchers’ expertise and models to help them improve the current situation, and to help Vietnam in developing the scientific infrastructure for a long-lasting science-policy interface for air quality management.

The project is helping Vietnamese researchers in a number of ways, including helping us to develop a multi-disciplinary research community in Vietnam on integrated air quality management, and in providing local decision makers with the capacity to develop cost-effective management plans for the Hanoi metropolitan area and surrounding regions and, in the longer-term, the whole of Vietnam.

About VAST and Ninh Khac Ban

VAST was established in 1975 by the Vietnamese government to carry out basic research in natural sciences and to provide objective grounds for science and technology management, for shaping policies, strategies and plans for socio-economic development in Vietnam. Ninh Khac Ban obtained his PhD in Biology from VAST’s Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources in 2001. He has managed several large research projects as a principal advisor, including several multinational joint research projects. His successful academic career has led to the publication of more than 34 international articles with a high ranking, and more than 60 national articles, and 2 registered patents. He has supervised 5 master’s and 9 PhD level students successfully to graduation and has contributed to pedagogical texts for postgraduate training in his field of expertise.

Notes:

More information on IIASA and Vietnam collaborations. This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 29, 2019 | USA, Young Scientists

By Matt Cooper, PhD student at the Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Maryland, and 2018 winner of the IIASA Peccei Award

I never pictured myself working in Europe. I have always been an eager traveler, and I spent many years living, working and doing fieldwork in Africa and Asia before starting my PhD. I was interested in topics like international development, environmental conservation, public health, and smallholder agriculture. These interests led me to my MA research in Mali, working for an NGO in Nairobi, and to helping found a National Park in the Philippines. But Europe seemed like a remote possibility. That was at least until fall 2017, when I was looking for opportunities to get abroad and gain some research experience for the following summer. I was worried that I wouldn’t find many opportunities, because my PhD research was different from what I had previously done. Rather than interviewing farmers or measuring trees in the field myself, I was running global models using data from satellites and other projects. Since most funding for PhD students is for fieldwork, I wasn’t sure what kind of opportunities I would find. However, luckily, I heard about an interesting opportunity called the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) at IIASA, and I decided to apply.

Participating in the YSSP turned out to be a great experience, both personally and professionally. Vienna is a wonderful city to live in, and I quickly made friends with my fellow YSSPers. Every weekend was filled with trips to the Alps or to nearby countries, and IIASA offers all sorts of activities during the week, from cultural festivals to triathlons. I also received very helpful advice and research instruction from my supervisors at IIASA, who brought a wealth of experience to my research topic. It felt very much as if I had found my kind of people among the international PhD students and academics at IIASA. Freed from the distractions of teaching, I was also able to focus 100% on my research and I conducted the largest-ever analysis of drought and child malnutrition.

© Matt Cooper

Now, I am very grateful to have another summer at IIASA coming up, thanks to the Peccei Award. I will again focus on the impact climate shocks like drought have on child health. however, I will build on last year’s research by looking at future scenarios of climate change and economic development. Will greater prosperity offset the impacts of severe droughts and flooding on children in developing countries? Or does climate change pose a hazard that will offset the global health gains of the past few decades? These are the questions that I hope to answer during the coming summer, where my research will benefit from many of the future scenarios already developed at IIASA.

I can’t think of a better research institute to conduct this kind of systemic, global research than IIASA, and I can’t picture a more enjoyable place to live for a summer than Vienna.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 6, 2019 | Data and Methods, Ecosystems, Systems Analysis, Young Scientists

By Davit Stepanyan, PhD candidate and research associate at Humboldt University of Berlin, International Agricultural Trade and Development Group and 2019 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) Award Finalist.

Participating in the YSSP at IIASA was the biggest boost to my scientific career and has shifted my research to a whole new level. IIASA provides a perfect research environment, especially for young researchers who are at the beginning of their career paths and helps to shape and integrate their scientific ideas and discoveries into the global research community. Being surrounded by leading scientists in the field of systems analysis who were open to discuss my ideas and who encouraged me to look at my own research from different angles was the most important push during my PhD studies. Having the work I did at IIASA recognized with an Honorable Mention in the 2019 YSSP Awards has motivated me to continue digging deeper into the world of systems analysis and to pursue new challenges.

© Davit Stepanyan

Although my background is in economics, mathematics has always been my passion. When I started my PhD studies, I decided to combine these two disciplines by taking on the challenge of developing an efficient method of quantifying uncertainties in large-scale economic simulation models, and so drastically reduce the need and cost of big data computers and data management.

The discourse on uncertainty has always been central to many fields of science from cosmology to economics. In our daily lives when making decisions we also consider uncertainty, even if subconsciously: We will often ask ourselves questions like “What if…?”, “What is the chance of…?” etc. These questions and their answers are also crucial to systems analysis since the final goal is to represent our objectives in models as close to reality as possible.

I applied for the YSSP during my third year of PhD research. I had reached the stage where I had developed the theoretical framework for my method, and it was the time to test it on well-established large-scale simulation models. The IIASA Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM), is a simulation model with global coverage: It is the perfect example of a large-scale simulation model that has faced difficulties applying burdensome uncertainty quantification techniques (e.g. Monte Carlo or quasi-Monte Carlo).

The results from GLOBIOM have been very successful; my proposed method was able to produce high-quality results using only about 4% of the computer and data storage capacities of the above-mentioned existing methods. Since my stay at IIASA, I have successfully applied my proposed method to two other large-scale simulation models. These results are in the process of becoming a scientific publication and hopefully will benefit many other users of large-scale simulation models.

Looking forward, despite computer capacities developing at high speed, in a time of ‘big data’ we can anticipate that simulation models will grow in size and scope to such an extent that more efficient methods will be required.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.