Aug 3, 2016 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience

By Adriana Keating, research scholar in the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program.

People have been playing games for fun for many thousands of years. But recently some have been designed not to escape from reality, but to improve it. As the world is becoming more and more complex, and the future more and more uncertain, serious games can be used as innovative tools for learning, decision making, improving effective collaboration and developing strategies for success. With games, we can communicate complex realities and learn from our mistakes without costs.

Systems thinking is required to tackle the challenge of managing both flood risk and development: to live in harmony with floods. Games provide the perfect avenue for exploring these challenges. Games that engage participants have been shown to be very successful and powerful dissemination instruments—with broader outreach than traditional reports. In a team made up of myself, Piotr Magnuszewski from the Water Program, Adam French from the Advanced Systems Analysis and Risk and Resilience Programs, and collaborators from the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance, we have been developing a game that can help build flood resilience in developing countries.

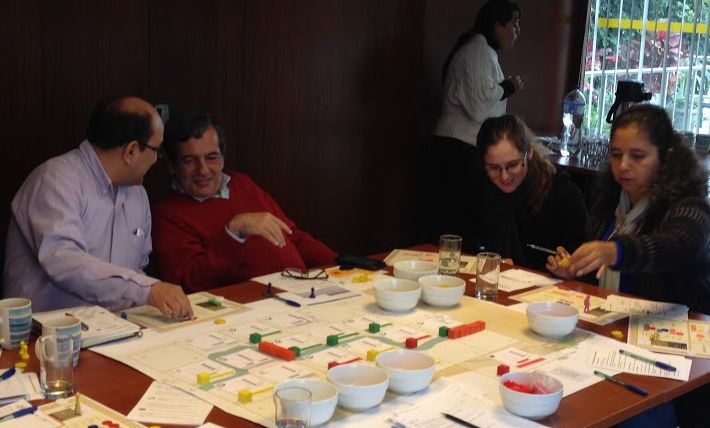

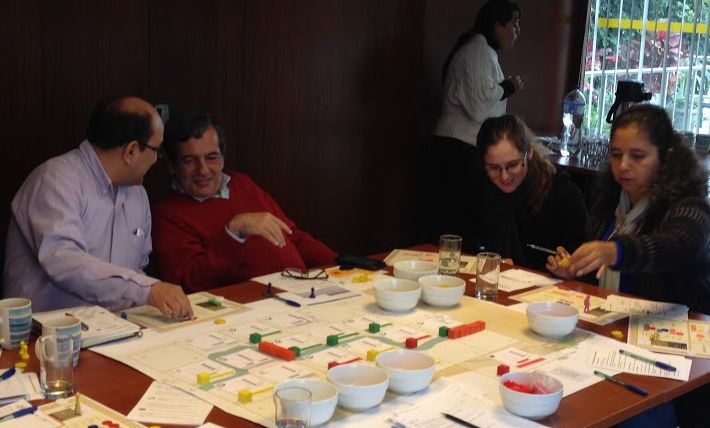

The game provoking discussion at a workshop in Jakarta. © Adriana Keating

Because games are experienced as something that feels real, more information is retained, learning is faster, and an intuition is gained about how to make real decisions. Critically, the IIASA Flood Resilience Game is designed to help participants— such as NGO staff working on flood-focused programs—to identify novel policies and strategies which improve flood resilience. In its current form it is a board-game played by at least eight players, who each take on a role as a member of a flood prone community. The direct interactions between players create a rich experience that can be discussed, analysed, and lead to concrete conclusions and actions. This allows players to explore vulnerabilities and capacities—citizens, local authorities and NGOs together—leading to an advanced understanding of interdependencies and the potential for working together.

The game draws on IIASA research on the deep-seated challenges in the typical approach to flood risk management. It allows players to experience, explore, and learn about the flood risk and resilience of communities in river valleys. It lets them experience the effects on resilience of investments in different types of “capital”—such as financial, human, social, physical, and natural. The impacts of flood damage on housing and infrastructure are also an important part of the game, as well as indirect effects on livelihoods, markets, and quality of life.

Players in Peru. © Adam French.

Playing the game can also improve understanding of the influence of preparedness, response, reconstruction on flood resilience. Importantly, it demonstrates the benefits of investment in risk reduction before the flood strikes, such as via land use planning and flood proofing homes. The effects of institutional arrangements, such as communication between citizens and with government, also become clearer during the course of the game.

Finally, participants can explore the complex outcomes on the economy, society and the environment from long-term development pathways. This highlights the types of decisions needed to avoid creating more flood risk in the future, incentivizing action before a flood through enhancing participatory decision-making. All these complex ideas are experienced with simple, concrete game elements that participants can connect with their daily realities.

From a researcher’s perspective, observing game play deepens our understanding of stakeholder motivations in relation to flood resilience. The game also contributes to better understanding and use of IIASA research via the Zurich flood resilience measurement tool, a ground-breaking approach to resilience measurement.

After several field tests in Jakarta and Lima with staff from the NGOs Practical Action, Red Cross Indonesia, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Mercy Corp, Plan and Concern Worldwide, the game is now being refined. The next version will be released soon, and the possibility of a mobile application to allow players to handle more complex dynamics while interacting in the workshop is being explored.

The game was developed in collaboration with the Centre for Systems Solutions, Poland, and with funding from the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 30, 2015 | Alumni, IIASA Network, Risk and resilience

By Bruce Beck, Imperial College London and Michael Thompson, IIASA Risk, Policy and Vulnerability (RPV) Program.

What do Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium in London, the now glorious heritage of Islington’s housing stock, and the cable-car system in Kathmandu for getting milk supplies to that city, all have in common?

They are (or were) all transformative in their own way. All are commendable outcomes from the process of city governance that we argue will be essential for Coping with Change, the subject of our working paper for the Foresight Future of Cities project. Each is a primary case study in the analysis of our paper. We call this kind of governance ‘clumsiness’. It is something that does not evoke any sense of the familiar attributes of suaveness, elegance, and consensuality implied and valued in most other kinds of governance. So what, then, makes this thing with such an awkward, provocative name so relevant to the future of cities?

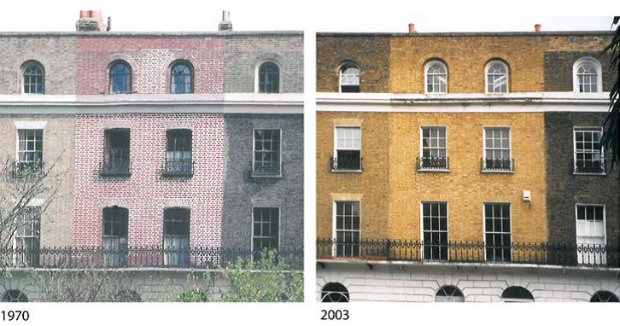

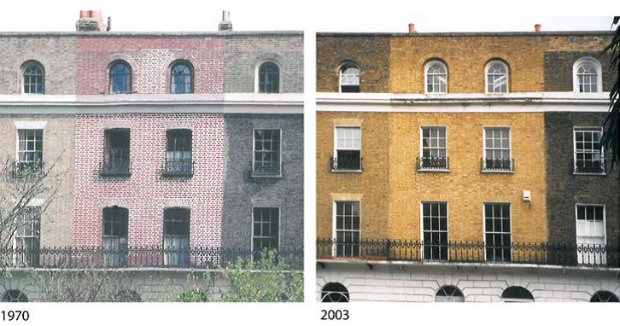

Before and after: Islington’s clumsy and resilient resurgence.

Imagine the city being buffeted about by all manner of social, economic, and natural disturbances over time. There will be times for taking risks with the city’s affairs, and times for avoiding them, or managing them, even just absorbing them – 4 mutually exclusive ways of apprehending how the world works, as it were, and 4 accompanying styles of coping.

In the financial industry, this risk typology has been referred to as the 4 seasons of risk. These are strategically and qualitatively different macroscopic regimes of system behaviour; coping with change between one and another of them is every bit as strategically significant. Conventionally, we recognise only 2 of these regimes: those giving rise to boom and bust in the economy. They reflect just 2 of the 4 ways of understanding the world and acting within it. The nub of the distinctive advantage of clumsiness over other forms of governance for coping with change and transformation is the richness of its (fourfold) diversity of perspective, from which may derive resilience and adaptability in the city’s response to any disturbance – big or small, economic, social, or natural.

Clumsiness is most assuredly deeply participatory. Its process is assiduously supportive of robust, noisy, disputatious debate: witness the gyrations in the Arsenal, Islington, and (especially so) Kathmandu case studies. This is exactly as one should expect of any meaningful engagement among the city’s stakeholders: the public-sector agencies, community activists, private-sector businesses, and so on, all with their own vested interests. The 4 ways of seeing the world are mutually opposed; each is sustained in its opposition to the others, as will be the shaping of their aspirations for the future. Each needs the challenges from the others, not least to avoid the ‘group-think’ in governance that is of such considerable concern to government in managing financial risk.

At the peak of deliberative quality in governance, all 4 outlooks are granted access and responsiveness in the debate, in the process of clumsiness, in other words, in coming to a decision or policy — with ever higher social consent. And in the clumsiest of outcomes, each opposing group gets more of what it wants, and less of what it does not want, at least for a while, until everything about the city’s affairs is revisited once again, as the various seasons of risk come around, each holding sway in turn. As we say in our working paper, clumsiness is why village communities in the Himalayas and Swiss Alps have remained viable over the centuries, without destroying either themselves (‘man’) or their environments (‘nature’) – sustainability par excellence, in other words.

So now we must ask: can cities be viable and sustainable in the same way as these mountain villages? In particular, how can the city’s built environment – the infrastructure that mediates between nature and man, the natural and human environments – be made resilient and adaptable, especially in an ecological sense? Thus might we possess this much prized attribute of systems behaviour in each of the natural, built, and human environments, and in a mutually reinforcing manner. What role might clumsiness have in all of this?

In closing our working paper, where we “connect the systemic dots” of our entire argument, we touch upon a computational foresight study in seeking a smarter urban metabolism for London. The fourfold typology of clumsiness is employed to define future target aspirations for the city (quantitatively expressed, under gross uncertainty). These should be the distant outcomes of the fourfold narratives of how the world is believed to work and what it is that each attaching vested interest much wants – and decidedly does not want. An inverse sensitivity analysis (redolent of a computational backcasting) identifies what is key (and what redundant) to the ‘reachability’ (or not) of each of the 4 sets of aspirations for the distant future. Imagine then the urine-separating toilet (UST) as the clumsy solution to a smarter metabolism for London – a smarter way, that is, of the city’s processing of the resource flows of water, energy, carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus passing through its social-economic life. Rather more grandly put, imagine instead the UST as a “privileged, non-foreclosing policy-technology innovation” for today!

Well now … if clumsiness is such a jolly good thing, what else might it do for us and our cities? We submit it promises the prospect of greater resilience and adaptability in the governance of innovation ecosystems, extending thus the lines of evidence recounted for re-invigoration of the industrial economy of NE Ohio in Katz & Bradley’s recent (2013) book Metropolitan Revolution. ‘Resilience’ and ‘ecosystem’ are (for now) ubiquitous in our everyday language. But no-one, as far as we are aware, has thought of applying the immensely rich notion of ecological resilience to orchestrating the creative and clumsy affairs of an innovation ecosystem. We are currently examining this.

Read the full report

Featured image by Peter McDermott. Used under Creative Commons.

For further information on the Foresight Future of Cities project visit: https://futureofcities.blog.gov.uk

48.05504316.352678

Feb 4, 2015 | Systems Analysis

By Elisabeth Suwandschieff, Research Scholar, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Vienna, Austria

We live in a world that is fluid and diverse. Yet policymakers have to find solutions to problems that are definitive and effective, able to adapt to uncertain, changing, and challenging environments. How can research help policymakers to achieve such resilience?

At last week’s 4th Viennese Talks on Resilience and Networks, I listened to a number of talks on this topic from prominent figures in politics, military, research, and the private sector who came together to discuss future potential pathways for Austria. Speakers from politics emphasized the importance of social solutions such as greater investment in education. Meanwhile researchers from IIASA and other institutions brought perspective from systems analysis methods and explained how research on dynamic systems can inform policy making.

System dynamics view

From the research perspective, IIASA’s Brian Fath and others brought a systems analytical view of complex systems and their dynamics. They explained that complex systems such as organizations, businesses, and cities go through different stages in their “ecocycle.” Understanding the cycle and process is key to influencing its development.

FAS.research Director Harald Katzmair argued that life, as a complex system, can be seen as a process of growth, stagnation, destructurization and reorganization. In a recent research project, Katzmair found that the main factor in achieving resilience was the ability of the system to remain flexible through improvisation, collaboration, behavioral change and openness. If we apply this to our understanding of the world it becomes necessary to rethink our approach to leadership in every aspect.

“Our world is not a closed system; it does not consist of one choice, one idea, one currency,” said Katzmair.

Fath said that resilience is achieved by successfully managing each stage of the life cycle, explaining that even collapse can be seen as a key feature of system dynamics, because it results in developmental opportunities. Through disturbance and adaptive change in the landscape, new landscapes can be shaped.

Applying research to resilience

Many of the research talks were mathematical and complex. How can such research help in achieving resilience on a practical level? The issue for policymakers is that they have to provide definitive solutions when actually we live in a world that is fluid and diverse – therefore we need a diversified portfolio of problem solving. That is, solutions must be broad without losing focus. They must be effective, but remain flexible and open.

Research can bring different experiences together, provide a platform and a common language that can be shared. Systems thinking is a powerful way to condense the different ways of thinking and produce a portfolio of options rather than provide rigid solutions.

The adaptive cycle (Burkhard et al. 2011)

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 18, 2014 | Systems Analysis

By Leena Ilmola-Sheppard, IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program

When government officials speak about risks, they are usually referring to natural disasters. And it seems in these discussions that the increasing frequency of flooding, droughts, snow storms, and hurricanes have no link to climate change nor mitigation of it.

Last week, I had an opportunity to sit and listen to discussions at the fourth annual Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) High Level Risk Forum. The objective of the forum is to initiate joint development of the national level risk management tools and procedures. National risk directors form their Prime Minister’s Offices and OECD ambassadors spent three rainy days from December 10-12 discussing risk.

The most of the time, the discussion centered around disaster risks. Whatever the theme of the session, the discussion ended up on disaster management, disaster costs, or best practices. This is a theme that was recognized to be of importance in every government. The other risks that were presented were terrorism, the Ebola epidemic, and illicit trade. The missing themes–that I had expected to be on the agenda–were technology related, financial risks and political risks.

Governments usually take risk to mean natural disasters – but missing from most discussions are climate change, technology, financial, and political risks. Here: storm clouds over England in September 2014. Photo Credit: Ched Cheddles via Flickr

Margaret Wahlstrom, Special Representative of the UN Secretary General for Disaster Risk Reduction, gave the best presentation. Her key message war that climate change related issues were not integrated well enough with risk management. Kate White from the US Army Corps of Engineers supported Wahlstrom by stating that the climate change will radically change disaster management goals, procedures, and volume of investment. There should be a strong motivation for that, she said, as disasters are coming more expensive. According to her data, the total cost of hurricane Sandy was 65 billion US$.

The Australian government calculations presented in the meeting are very revealing as well; from Australian government is spending around 400 million AU$ for disaster prevention and response, and 2.6 billion AU$ for recovery. As the Australian example shows, governments have a long way to go from words to action. Governments have not yet realized the role of mitigation, at least not in the budgeting level.

The main theme of this year’s forum was “risk and resilience.” So the word was used a lot in all of the presentations. However, the concept of resilience seems to have many meanings and concrete substance behind the word is ambiguous. Margaret Wahlstrom pointed out that there is a need for a cross-discipline understanding of resilience, as well as for a generic resilience measurement system. Concrete quantitative indicators would help policymakers to assess the development actions needed, improvement achieved, and provide justification for development actions.

The most vivid discussion concerned the relationship of the national risk management and public involvement. Countries such as the United Kingdom promote full transparency and active risk communications, while some of the governments such as Singapore focus on communicating the vision and improvement ideas instead of risks. My interpretation of the discussion is that many of the represented government experts perceive risks to be too complicated to communicate to a general audience. The Nordic countries even go beyond communication, to encourage and support self-organized actions. For example the government supported people when they started to offer shelter and places to sleep for those that got stuck on the road during the October storms of this year, the worst to hit the region in decades.

Read the forum’s summary document draft (PDF)

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 19, 2014 | Risk and resilience

By Junko Mochizuki, Adriana Keating and Reinhard Mechler, IIASA Risk, Policy, and Vulnerability Program

Flood in Davao City, Philippines, January 20, 2013. Photo credit: Jeff Pioquinto via Flickr

The year 2015 will mark a crucial milestone for the international development, climate change, and disaster management communities. Negotiations are currently underway to hammer out three landmark decisions: a much anticipated global climate deal to be agreed at the COP21 meeting in Paris, a new agreement on post-Millenium Development Goals known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the post-Hyogo disaster risk reduction framework (HFA2) to be adopted at the 2015 World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in Sendai. The outcomes of these three international forums will largely shape the global agendas for the next few decades.

The HFA2 builds on the knowledge and experience gained from 10 years of implementation of the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) 2005-2015, the first international initiative to offer a global blueprint for disaster risk reduction. Since its inception, 22 core indicators have been developed to monitor global progress across five priority areas, including building a culture of safety and enhancing national and local institutional architecture. The implementation has thus far shown mixed progress. The key remaining issue is the underlying drivers of risk and that the HF2 must address both the correction of existing risk and prevention of future risk creation.

On 10 and 11 February, the world’s leading experts on disaster risk management gathered at IIASA to begin designing an effective HFA2 monitoring system. At the meeting, co-organized with the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR), participants deliberated how the HFA2 monitoring system could address the remaining issues of risk creation, mainstreaming, and resilience building, and inform ongoing discussions on SDGs and climate change mitigation and adaptation.

The meeting participants emphasized that the notion of resilience to natural disasters or other unexpected events offers a unique entry point for shared discussions across the development, disaster, and climate change research and policy communities. The resilience notion of “bouncing-forward” stresses that societies must understand the risks they face, and be prepared use both pre- and post-disaster opportunities to implement policies that can reduce risk and advance development objectives. These are important additions to the disaster risk management debate which are essential to the post-2015 approach.

But many challenges remain. We need a concrete set of indicators to measure the multi-dimensional concept of disaster resilience. While we expect to see the adoption of quantitative disaster risk reduction targets—such as mortality, affected population, or economic loss reduction, we do not yet have a globally agreed methodology to measure disaster loss and damage. More fundamentally, an emphasis on loss data could send the world a wrong signal that disaster loss is all that matters. This speaks contrary to IIASA’s ongoing research. What we have found time and time again is that what matters most is a country’s steady management of underlying risk and resilience, whether or not a disaster has occurred.

As negotiations continue towards the climate, development, and disaster goals, it is clear that effective framework must be organized around a holistic understanding of well being and its systemic components. Over the coming months, researchers and analysts including IIASA staff will work with UNISDR to develop a global framework linking the concepts of risk and resilience.

About the authors

Junko Mochizuki and Adriana Keating are research scholars and Reinhard Mechler is the deputy program leader in IIASA’s Risk, Policy, and Vulnerability Program. Their current work at IIASA focuses on advancing the notion of disaster resilience, evaluating how novel and participatory system analysis tools may be used to inform policy on disaster resilience building.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

00

You must be logged in to post a comment.