Nov 26, 2021 | Demography, Environment, Finland, IIASA Network, Poverty & Equity

By Venla Niva, DSc researcher with the Water and Development Research Group, School of Engineering, Aalto University, Finland

Venla Niva shares insights from a recent article exploring the interplay of environmental and social factors behind human migration. The project was carried out in collaboration with Raya Muttarak from the IIASA Population and Just Societies Program.

© Irina Nazarova | Dreamstime.com

Environmental migration has gained increasing attention in the past years, with recent climate reports and policy documents highlighting an increase in environmental refugees and migrants as one of the potential effects of the warming globe. Policymaking is dominated by a narrative that portrays environmental migration as a security threat to the “Global North”. Meanwhile, researchers around the world have put enormous efforts into understanding environmental migration and what is driving it. Yet, the causes and effects of environmental migration remain under debate.

In our latest paper, we extend the understanding of environmental migration by looking into how environmental and societal factors interacted in places of excess out- or in-migration between 1990 and 2000. We found that understanding these interactions is key for understanding migration drivers. Ultimately, migration is based on human decision-making, and in our view “simply cannot and should not be studied without the inclusion of the societal dimension: human capacity and agency.” Our findings were both expected and, to a certain degree, surprising.

Our results show that the majority of global migration takes place in areas with rather similar profiles. It is known that migration mostly occurs over short distances, and that internal migration – in other words, people moving around in their own country – outplays international migration – people moving between countries – by significant numbers globally. This, however, shows that the characteristics of these areas are alike too. High environmental stress coupled with low-to-moderate human capacity characterized these areas at both ends of migration. Such characteristics portray a combination of variables with a high degree of drought and water risks, natural hazards, and food insecurity, but low levels of income, education, health, and governance.

We found that income was the best variable to explain the variation of net-negative and net-positive migration in around half of the countries, globally, confirming that income is a good predictor of migration. This is interesting in two ways. According to traditional migration theories, income disparity between regions is seen as the primary driver for migration. Yet, income only dominated the other variables in half of the countries we examined. Education and health were especially important in areas with more out-migration than in-migration. Drought and water risks were important explaining factors in many countries, but were outranked by societal factors such as income, health, education, and governance in the majority of countries.

In light of our research, we would like to point out that it is unlikely that environmental factors alone would be responsible for migration. Instead, the role of human agency is vital. Investments in building human capacity have two-fold benefits: First, higher human capacity facilitates not only local adaptation to changes in the environment, but also adaptation at the destination in case of migrating. Second, protecting ecosystems and the environment helps to mitigate and adapt to climate and environmental change in areas with high environmental stress, which is again crucial for maintaining livelihoods and a good life at both ends of migration.

Environmental migration is often portrayed by the media as a catastrophic phenomenon. Our study confirms that migration drivers are a result of the interactions between socioeconomic and environmental factors and that human capacity plays a central role in both enabling the migration process and adaptation at the place of destination.

Further info:

Niva, V., Kallio, M., Muttarak, R., Taka, M., Varis, O., & Kummu, M. (2021). Global migration is driven by the complex interplay between environmental and social factors. Environmental Research Letters DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac2e86. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17507]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 4, 2021 | Climate Change, Data and Methods, Risk and resilience

By Asjad Naqvi and Irene Monasterolo from the IIASA Advancing Systems Analysis Program

Asjad Naqvi and Irene Monasterolo discuss a framework they developed to assess how natural disasters cascade across socioeconomic systems.

© Bang Oland | Dreamstime.com

The 2021 Nobel Prize for Physics, was awarded to the topic of “complex systems”, highlighting the need for a better understanding of non-linear interactions that take place within natural and socioeconomic systems. In our paper titled “Assessing the cascading impacts of natural disasters in a multi-layer behavioral network framework”, recently published in Nature Scientific Reports, we highlight one such application of complex systems.

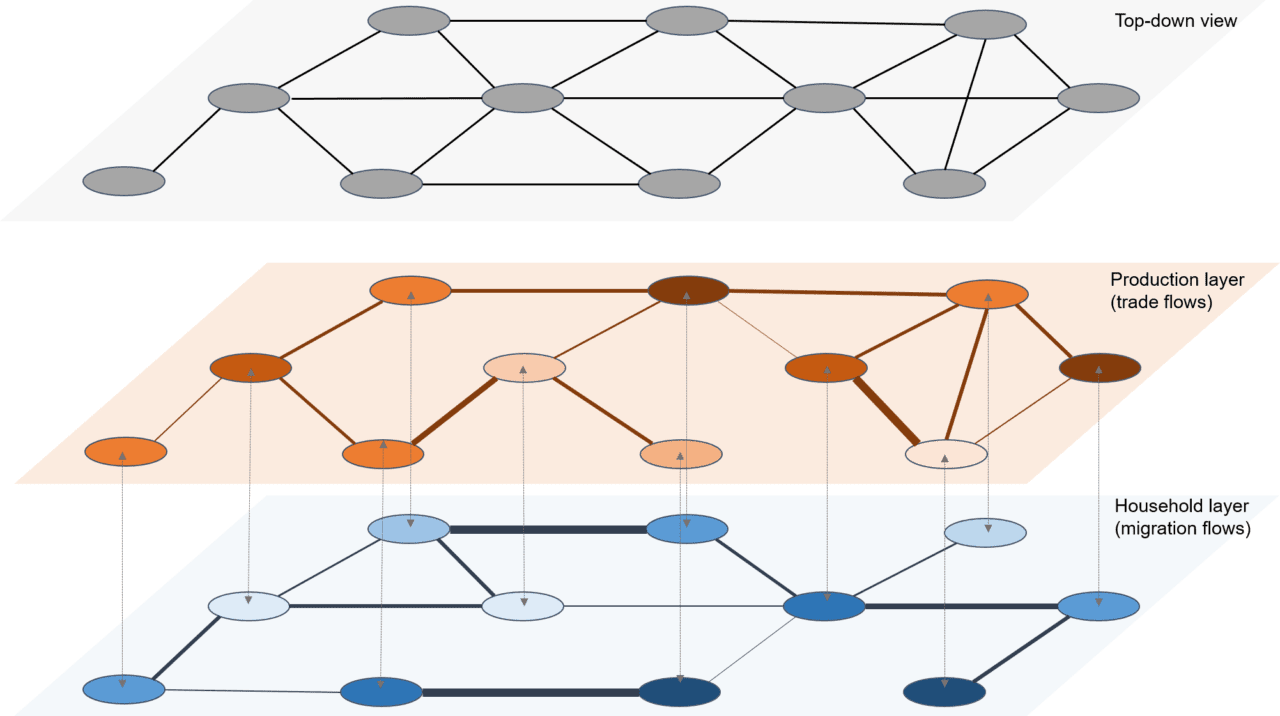

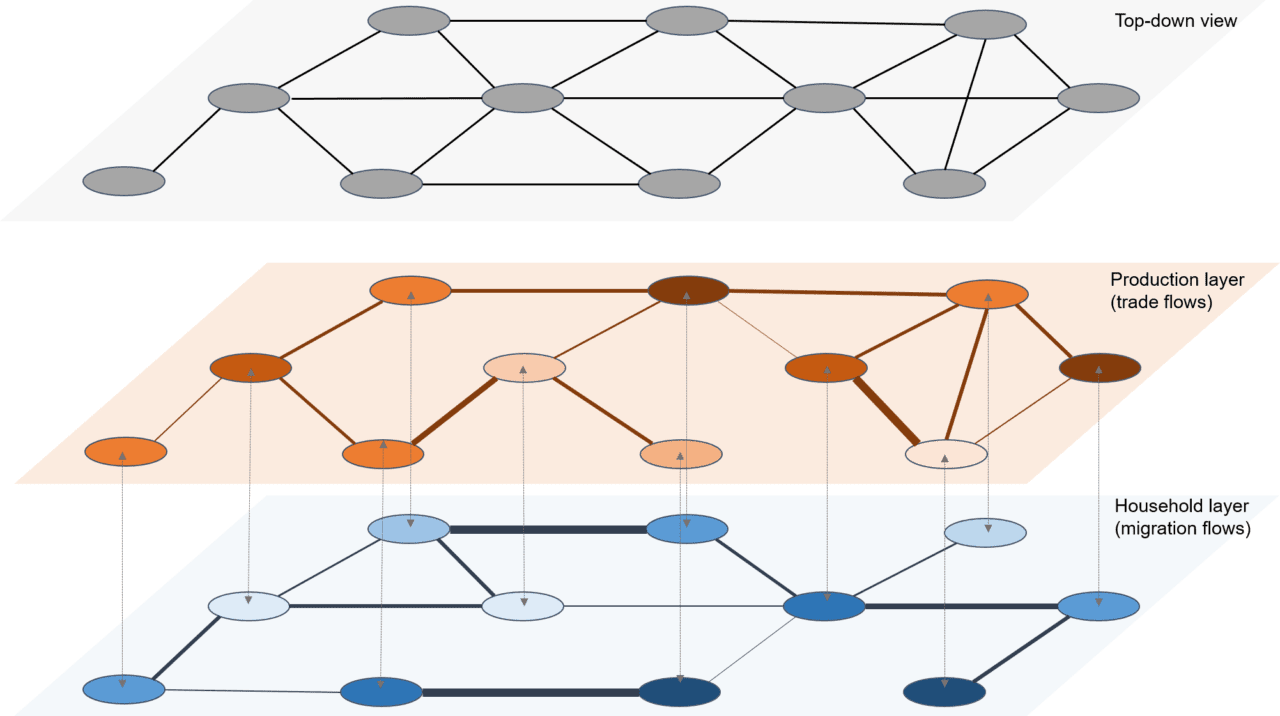

In this paper, we develop a framework for assessing how natural disasters, for example, earthquakes and floods, cascade across socioeconomic systems. We propose that in order to understand post-shock outcomes, an economic structure can be broken down into multiple network layers. Multi-layer networks are a relatively new methodology, mostly stemming from applications in finance after the 2008 financial crisis, which starts with the premise that nodes, or locations in our case, interact with other nodes through various network layers. For example, in our study, we highlight the role of a supply-side production layer, where the flows are trade networks, and a demand-side household layer, which provides labor, and the flows are migration flows.

Figure 1: A multi-layer network structure

In this two-layer structure, the nodes interact, not only within, but across layers as well, forming a co-evolving demand and supply structure that feeds back across each other. The interactions are derived from economic literature, which also allow us to integrate behavioral responses to distress scenarios. This, for example, includes household coping mechanisms for consumption smoothing, and firms’ response to market signals by reshuffling supply chains. The price signals drive flows, which allows the whole system to stabilize.

We applied the framework to an agriculture-dependent economy, typically found in low-income disaster-prone regions. We simulated various flood-like shock scenarios that reduce food output in one part of the network. We then tracked how this shock spreads to the rest of the network over space and time.

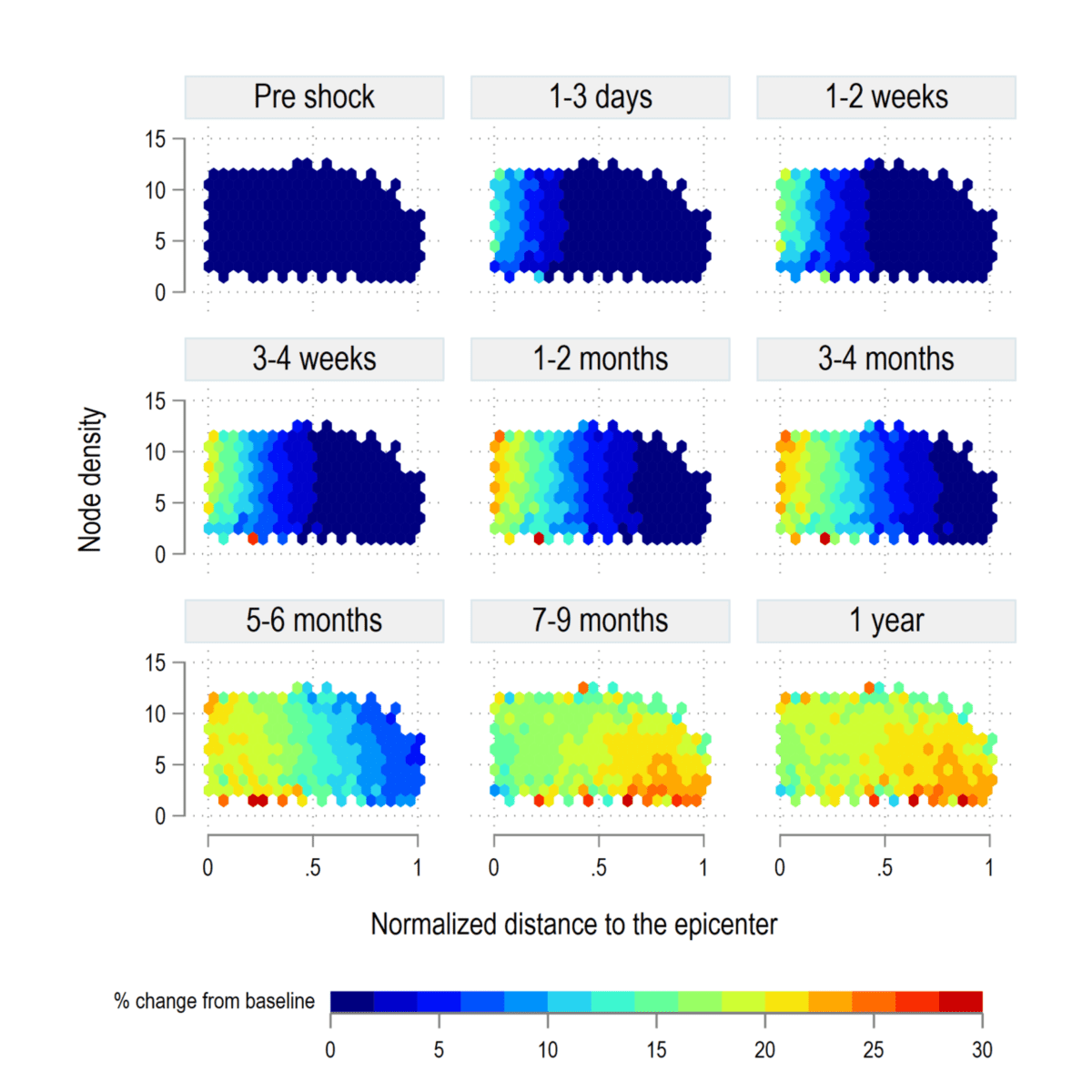

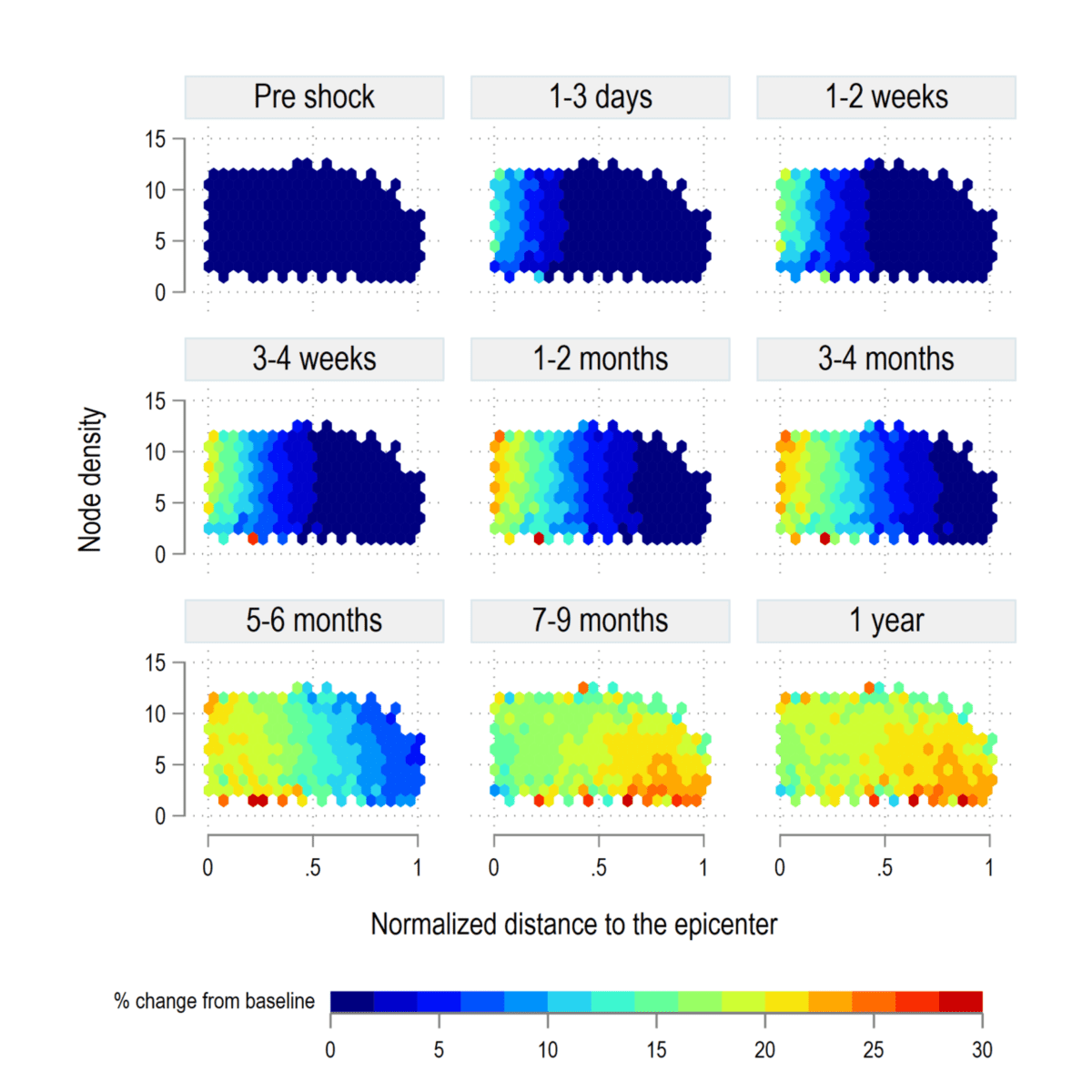

Figure 2: Evolution of vulnerability over time

Our results show that the transition phase is cyclical and depends on the network size, distance from the epi-center of the shock, and node density. Within this cyclical adjustment new vulnerabilities in terms of “food insecurity” can be created. Then, we introduce a new measure, the Vulnerability Rank, or VRank, to synthesize multi-layer risks into a single index.

Our framework can help inform and design policies, aimed at building resilience to disasters by accounting for direct and indirect cascading impacts. This is especially crucial for regions where the fiscal space is limited and timing of response is critical.

Reference:

Naqvi, A. & Monasterolo, I. (2021). Assessing the cascading impacts of natural disasters in a multi-layer behavioral network framework. Scientific Reports 11 e20146. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17496]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 18, 2021 | Climate, Climate Change, Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Marina Andrijevic, researcher in the IIASA Energy, Climate, and Environment Program

Marina Andrijevic tackles some inconvenient but fundamental issues around climate change adaptation.

© Lio2012 | Dreamstime.com

Anyone who followed climate-related headlines this summer would have noticed a more than usual amount of talk on climate change adaptation. As it goes with sudden epiphanies in aftermaths of humanitarian disasters in our Western realities, this time we’ve come to realize that we need to seriously think about doing some adaptation.

To be fair, the realization that adaptation is inevitable has for a long time been somewhat of a taboo in the “woke” climate policy and activist circles (the author of this blog is a millennial and would like to acknowledge that the reader’s idea of a long time in climate policy might be different). Admitting that there might be no other option but to adapt to whatever the locked-in effects of climate change are, is arguably defeatist and gives in to the notion that mitigation alone won’t cut it.

While this might be yet another depressing but accurate reflection of the reality under climate change, portraying adaptation and mitigation as different but equally urgent actions could set a dangerous trap if it produces ideas such as: if we adapt enough, perhaps our economies and energy systems won’t need to change so much.

Even if it would be enough (which it wouldn’t), adaptation will not necessarily just happen once we recognize it needs to be done, because the needs and abilities for it operate on different time horizons and geographical scales. Many parts of the world that need adaptation will not necessarily be able to take action, so we have to be very careful when we count on it as a solution to climate change.

This is where we must tackle some inconvenient but fundamental issues about adaptation. Climate change research, especially the areas positioned at the “interface” with policy, could play a crucial role here. In this role, it must be very prudent and avoid doing a disservice to decision makers, and even worse, to people affected by those decisions. In other words, the scientific assessments need to be careful when assuming for whom, where, and how adaptation can reasonably be expected.

We tried to illustrate why this matters in our recent paper that looks at the capacity of populations to adapt to heat stress. We used air-conditioning as a popular, albeit not (yet) climate-friendly adaptation option. My coauthors and I understand that air conditioning could well be maladaptation, meaning that it causes more harm than good in the long-run. Adaptation practices, however, it turns out, are quite difficult to measure, while installed air conditioners can literally be counted, which makes them handy for plugging into our statistical models. We contend with access to air conditioning currently being a good enough example of access to adaptation and promise to assess more options in the future.

Our paper shows how the capacities to protect against heat stress vary widely around the world. Like with many other unjust manifestations of climate change, people in the world’s hottest areas also have the least means to adapt. We found that countries with more income, more urban areas, and less income inequality, are also the ones where more people have access to air conditioning.

This does not come as the world’s biggest revelation, but it conveniently allows us to make informed guesses on how access to air conditioning might change in 2050 or 2100. This is possible because the research community has already engaged in a group effort to propose five different futures with regard to GDP, urbanization, and income distribution (in climate jargon: the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways or SSPs).

Coupling the potential rates of air conditioning with the people exposed to heat stress based on projections of climate models, lets us calculate the cooling gap – the difference between people exposed to heat stress and people who can protect themselves against it with the use of air conditioning.

Depending on whether we find ourselves in the best- or the worst-case scenario of socioeconomic development could mean anywhere between two billion and five billion people globally unable to protect themselves against heat stress with air conditioning in 2050. This range only grows with longer time horizons, with Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia being the areas of the world where these differences are the starkest.

We hope that our paper will motivate further investigations of potential gaps in adaptation that point to insufficient adaptive capacity and help to identify the areas and populations most at risk, as well as what additional work needs to be done in terms of socioeconomic improvements before we can reasonably expect adaptation to take place. Our findings on the importance of factors beyond just GDP, suggest that helping communities to build their adaptive capacity doesn’t mean only throwing money at them (although that would make for a decent start!), but international efforts must focus on issues such as eradicating inequalities, supporting smart urban development, strengthening institutions, and providing education.

So, let’s not take it for granted that we will all be able to adapt either now or in the future. Eliminating the causes of climate change must remain the number one policy objective that will help to reduce the need for adaptation in the first place. But number two could be helping communities that have no option but to cope with what’s already coming at them. Highlighting in our research what the implications of different adaptive capacities are for preservation of livelihoods, is a small step towards achieving this.

Reference:

Andrijevic, M., Byers, E., Mastrucci, A., Smits, J., & Fuss, S. (2021). Future cooling gap in shared socioeconomic pathways. Environmental Research Letters 16 (9) e094053. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17411]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 29, 2021 | Korea, Science and Policy, Young Scientists

By Fanni Daniella Szakal, 2021 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Despite the political challenges, 2021 YSSP participant Eunbeen Park is researching ways to restore forests in isolated North Korea.

© Znm | Dreamstime.com

North Korea is somewhat of an enigma and getting a glimpse into what transpires behind its borders is a difficult task. Based on our limited information, it however seems that its once luscious forests have disappeared at an alarming rate in the last few decades.

Deforestation in North Korea is fueled by economic difficulties, climate change, and a lack of information for effective forest management. As forests are recognized as important carbon sinks that are invaluable when working towards the climate goals established in the Paris Agreement, finding a way to restore them is imperative. Forests are also essential in solving food insecurity and energy issues, which is especially relevant in the face of the current economic hardship in North Korea.

Neighboring South Korea serves as a benchmark for a successful reforestation campaign after having restored most of its forest cover in the last half a century. South Korean researchers and NGOs are keen to support afforestation efforts in North Korea and it seems that the North Korean government is also prioritizing this through a 10-year plan announced by North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un in 2015. The strained relationship between the two Koreas however, often hinders effective collaboration.

‘’We are close to North Korea regionally, but direct connection is difficult for political reasons. However, many researchers are interested in studying North Korea and there are currently many projects for South and North Korea collaboration supported by the Ministry of Unification,” says Eunbeen Park, a participant in the 2021 Young Scientists Summer Program and a second year PhD student in Environmental Planning and Landscape Architecture at Korea University in Seoul, South Korea.

North Korean countryside © Znm|Dreamstime.com

Modeling afforestation scenarios in North Korea

Park specializes in using remote sensing data for environmental monitoring and detecting changes in land cover. During her time at IIASA, she will use the Agriculture, Forestry, and Ecosystem Services Land Modeling System (AFE-LMS) developed by IIASA to support forest restoration in North Korea.

First, Park will use land cover maps dating back to the 1980s to map the change in forest cover. She will then identify areas for potential afforestation considering land cover change, forest productivity, climate, and different environmental variables, such as soil type. She will also develop different afforestation scenarios based on forest management options and the tree species used.

According to Andrey Krasovskiy, Park’s supervisor at IIASA, when selecting tree species for afforestation we need to take into account their economic, environmental, and recreational values.

“From a set of around 10 species we need to choose those that would be the most suitable in terms of resilience to climate change and to disturbances such as fire and beetles,” he says.

Challenges in data collection

A major challenge in Park’s research is obtaining accurate information for building her models. If there is relevant research from North Korea, it is not available to foreign researchers and without being able to enter the country to collect field data in person, her research has to rely on remote sensing data or data extrapolated from South Korean studies.

Fortunately, in recent years, remote sensing technology has evolved to provide high-resolution satellite data through which we are able to take a thorough look at the land cover of the elusive country. Park will match these maps with yield tables provided by Korea University based on South Korean data. As the ecology of the two Koreas are largely similar, these maps are thought to provide accurate results.

Is there space for science diplomacy?

“Research shouldn’t have any boundaries,” notes Krasovskiy. “In reality however, the lack of scientific collaboration between research groups in South and North Korea poses a major obstacle in turning this research into policy. Luckily, some organizations, such as the Hanns Seidel Foundation in South Korea, are able to bridge the gap and organize joint activities that provide hope for a more collaborative future.”

Despite the diplomatic hurdles, Park hopes that her work will find its way to North Korean policymakers.

“I expect my research might make a contribution to help policymakers and scientific officials establish forest relevant action in North Korea,” she concludes.

Jul 19, 2021 | IIASA Network, Risk and resilience, Women in Science

By Raquel Guimaraes, guest research scholar in the IIASA Migration and Sustainable Development and Equity and Justice research groups and assistant professor at the Federal University of Parana in Brazil

IIASA Network and Alumni Officer, Monika Bauer, recently invited me to participate in a genuinely important event hosted on IIASA Connect with the aim of gathering the IIASA community to discuss the gender dimension in research. As a gender researcher, this topic is part of my daily activities, and I decided to focus on the most important findings of my research: gender, disasters, and climate change.

© Raquel Guimaraes

In my talk, I gave an overview of the data relating to gender and disasters. According to the United Nations Development Programme, disasters lower women’s life expectancy more than men’s; moreover, women and children are 14 times more likely to die during a disaster. For example, most of the victims trapped in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina were African-American women and their children.

Given these facts, it becomes clear that gender is an important dimension of disaster and climate change research. Why is that? First, because gender and natural disasters are socially constructed under different geographic, cultural, political-economic, and social conditions and it has complex social consequences for both women and men. They therefore highlight societal, cultural, and religious norms and values, and shape the needs and risks of the affected individuals. Second, because disasters often affect women, girls, men, and boys differently due to gender inequalities caused not only by socioeconomic conditions, but also by cultural beliefs and traditional practices.

In addition to the above, climate change is connected to an increase in the frequency and/or severity of natural disasters such as flooding, heat waves, and cyclones. Disasters will therefore exacerbate existing inequalities and vulnerabilities in communities, since, as already mentioned, they have a wide range of effects for men and women, as well as for youth and children in both developing and developed countries.

Interestingly, the discussion on the intersection between gender and disasters is not new. References to gender as an issue in climate change debates and international protocols on disaster management have been made since at least the 1994 Yokohama World Conference on Natural Disaster Reduction. Since then, the international community has repeatedly called for gender-responsive disaster risk management.

To ensure gender equality and to overcome problems of marginalization, invisibility, and under-representation, gender concerns and women’s issues has been included into mainstream disaster risk reduction policies. Hence, understanding different gender roles, responsibilities, needs, and capacities to identify, reduce, prepare, and respond to disasters, is crucial to promoting effective disaster risk management.

Given the gender dimension of climate change and disaster research, some important questions that come to mind are: Do women really lack power in disasters? Are they really the fragile gender? The answer is: not always. Evidence shows that, despite gender-differentiated vulnerabilities, women and girls are also powerful agents of positive change before, during, and after disasters.

My research on floods, for instance, shows that in Brazil and Thailand, women can be agents of change. Preparedness to natural disasters have been recognized as key in disaster risk management to the extent that local and international actors emphasize the importance of saving lives and avoiding losses, even before the onset of a disaster. If there are different strategies for disaster prevention according to gender, then emergency management agencies and policymakers should account for these differences, ensuring that men and women combine their strengths to maximize preparedness for floods. Through data from two surveys, I evaluated preparedness by assessing several indicators that accounts for the provision of protective items, emergency plans, and the availability of insurance or information. Using econometric models, I found that women play an active role in disasters, being resourceful actresses in times of crises.

Therefore, during the IIASA Connect Coffee Talk I asserted that gender should be integrated as the basis of a complex and dynamic set of social relations in disaster and climate change research. I appreciate the opportunity IIASA Connect gave me to reflect on this issue with colleagues.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.