May 24, 2019 | Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Sustainable Development

By Pallav Purohit, researcher with the IIASA Air Quality and Greenhouse Gases Program

More than 300 million people in Hindu Kush Himalaya-countries still lack basic access to electricity. Pallav Purohit writes about recent research that looked into how the issue of energy poverty in the region can be addressed.

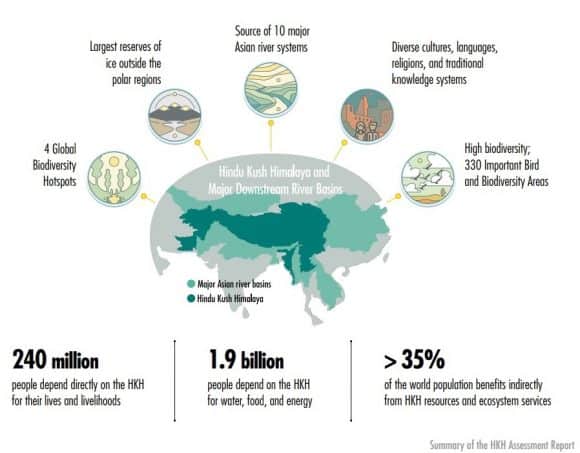

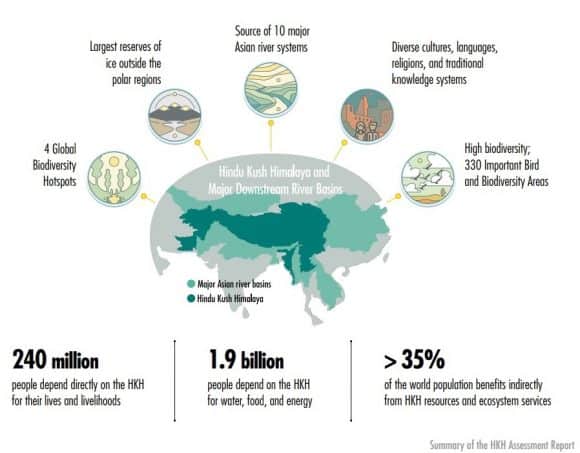

The Hindu Kush Himalayas is one of the largest mountain systems in the world, covering 4.2 million km2 across eight countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan. The region is home to the world’s highest peaks, unique cultures, diverse flora and fauna, and a vast reserve of natural resources.

Ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all – the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 – has however been especially elusive in this region, where energy poverty is shockingly high. About 80% of the population don’t have access to clean energy and depend on biomass – mostly fuelwood – for both cooking and heating. In fact, over 300 million people in Hindu Kush Himalaya-countries still lack basic access to electricity, while vast hydropower potentials remain largely untapped. Although a large percentage of these energy deprived populations live in rural mountain areas that fall far behind the national access rates, mountain-specific energy access data that reflects the realities of mountain energy poverty barely exists.

Source: Wester et al. (2019)

The big challenge in this regard is to simultaneously address the issues of energy poverty, energy security, and climate change while attaining multiple SDGs. The growing sectoral interdependencies in energy, climate, water, and food make it crucial for policymakers to understand cross-sectoral policy linkages and their effects at multiple scales. In our research, we critically examined the diverse aspects of the energy outlook of the Hindu Kush Himalayas, including demand-and-supply patterns; national policies, programmes, and institutions; emerging challenges and opportunities; and possible transformational pathways for sustainable energy.

Our recently published results show that the region can attain energy security by tapping into the full potential of hydropower and other renewables. Success, however, will critically depend on removing policy-, institutional-, financial-, and capacity barriers that now perpetuate energy poverty and vulnerability in mountain communities. Measures to enhance energy supply have had less than satisfactory results because of low prioritization and a failure to address the challenges of remoteness and fragility, while inadequate data and analyses are a major barrier to designing context specific interventions.

In the majority of Hindu Kush Himalaya-countries, existing national policy frameworks currently primarily focus on electrification for household lighting, with limited attention paid to energy for clean cooking and heating. A coherent mountain-specific policy framework therefore needs to be well integrated in national development strategies and translated into action. Quantitative targets and quality specifications of alternative energy options based on an explicit recognition of the full costs and benefits of each option, should be the basis for designing policies and prioritizing actions and investments. In this regard, a high-level, empowered, regional mechanism should be established to strengthen regional energy trade and cooperation, with a focus on prioritizing the use of locally available energy resources.

© Kriangkraiwut Boonlom | Dreamstime.com

Some countries in the region have scaled up off-grid initiatives that are globally recognized as successful. We however found that the special challenges faced by mountain communities – especially in terms of economies of scale, inaccessibility, fragility, marginality, access to infrastructure and resources, poverty levels, and capability gaps – thwart the large-scale replication of several best practice innovative business models and off-grid renewable energy solutions that are making inroads into some Hindu Kush Himalayan countries.

This further highlights an urgent need to establish supportive policy, legal, and institutional frameworks as well as innovations in mountain-specific technology and financing. In addition, enhanced multi-stakeholder capacity building at all levels will be needed for the upscaling of successful energy programs in off-grid mountain areas.

Finally, it is important to note that sustainable energy transition is a shared responsibility. To accelerate progress and make it meaningful, all key stakeholders must work together towards a sustainable energy transition. The world needs to engage with the Hindu Kush Himalayas to define an ambitious new energy vision: one that involves building an inclusive green society and economy, with mountain communities enjoying modern, affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy to improve their lives and the environment.

References:

[1] Dhakal S, Srivastava L, Sharma B, Palit D, Mainali B, Nepal R, Purohit P, Goswami A, et al. (2019). Meeting Future Energy Needs in the Hindu Kush Himalaya. In: The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment. pp. 167-207 Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15666]

[2] Wester P, Mishra A, Mukherji A, Shrestha AB (2019). The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 29, 2019 | USA, Young Scientists

By Matt Cooper, PhD student at the Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Maryland, and 2018 winner of the IIASA Peccei Award

I never pictured myself working in Europe. I have always been an eager traveler, and I spent many years living, working and doing fieldwork in Africa and Asia before starting my PhD. I was interested in topics like international development, environmental conservation, public health, and smallholder agriculture. These interests led me to my MA research in Mali, working for an NGO in Nairobi, and to helping found a National Park in the Philippines. But Europe seemed like a remote possibility. That was at least until fall 2017, when I was looking for opportunities to get abroad and gain some research experience for the following summer. I was worried that I wouldn’t find many opportunities, because my PhD research was different from what I had previously done. Rather than interviewing farmers or measuring trees in the field myself, I was running global models using data from satellites and other projects. Since most funding for PhD students is for fieldwork, I wasn’t sure what kind of opportunities I would find. However, luckily, I heard about an interesting opportunity called the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) at IIASA, and I decided to apply.

Participating in the YSSP turned out to be a great experience, both personally and professionally. Vienna is a wonderful city to live in, and I quickly made friends with my fellow YSSPers. Every weekend was filled with trips to the Alps or to nearby countries, and IIASA offers all sorts of activities during the week, from cultural festivals to triathlons. I also received very helpful advice and research instruction from my supervisors at IIASA, who brought a wealth of experience to my research topic. It felt very much as if I had found my kind of people among the international PhD students and academics at IIASA. Freed from the distractions of teaching, I was also able to focus 100% on my research and I conducted the largest-ever analysis of drought and child malnutrition.

© Matt Cooper

Now, I am very grateful to have another summer at IIASA coming up, thanks to the Peccei Award. I will again focus on the impact climate shocks like drought have on child health. however, I will build on last year’s research by looking at future scenarios of climate change and economic development. Will greater prosperity offset the impacts of severe droughts and flooding on children in developing countries? Or does climate change pose a hazard that will offset the global health gains of the past few decades? These are the questions that I hope to answer during the coming summer, where my research will benefit from many of the future scenarios already developed at IIASA.

I can’t think of a better research institute to conduct this kind of systemic, global research than IIASA, and I can’t picture a more enjoyable place to live for a summer than Vienna.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 24, 2019 | Data and Methods, Systems Analysis, Women in Science

By Sibel Eker, IIASA postdoctoral research scholar

Ceci n’est pas une pipe – This is not a pipe © Jaka Vukotič | Dreamstime.com

Quantitative models are an important part of environmental and economic research and policymaking. For instance, IIASA models such as GLOBIOM and GAINS have long assisted the European Commission in impact assessment and policy analysis2; and the energy policies in the US have long been guided by a national energy systems model (NEMS)3.

Despite such successful modelling applications, model criticisms often make the headlines. Either in scientific literature or in popular media, some critiques highlight that models are used as if they are precise predictors and that they don’t deal with uncertainties adequately4,5,6, whereas others accuse models of not accurately replicating reality7. Still more criticize models for extrapolating historical data as if it is a good estimate of the future8, and for their limited scopes that omit relevant and important processes9,10.

Validation is the modeling step employed to deal with such criticism and to ensure that a model is credible. However, validation means different things in different modelling fields, to different practitioners and to different decision makers. Some consider validity as an accurate representation of reality, based either on the processes included in the model scope or on the match between the model output and empirical data. According to others, an accurate representation is impossible; therefore, a model’s validity depends on how useful it is to understand the complexity and to test different assumptions.

Given this variety of views, we conducted a text-mining analysis on a large body of academic literature to understand the prevalent views and approaches in the model validation practice. We then complemented this analysis with an online survey among modeling practitioners. The purpose of the survey was to investigate the practitioners’ perspectives, and how it depends on background factors.

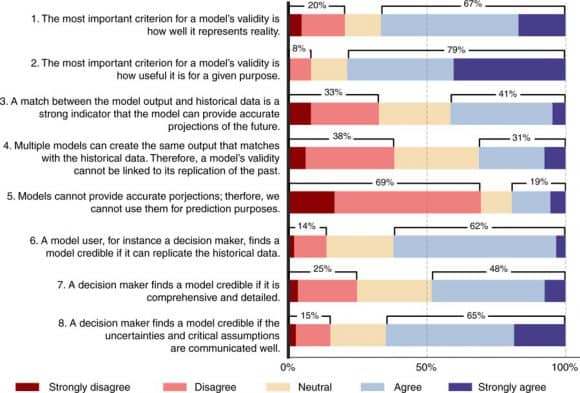

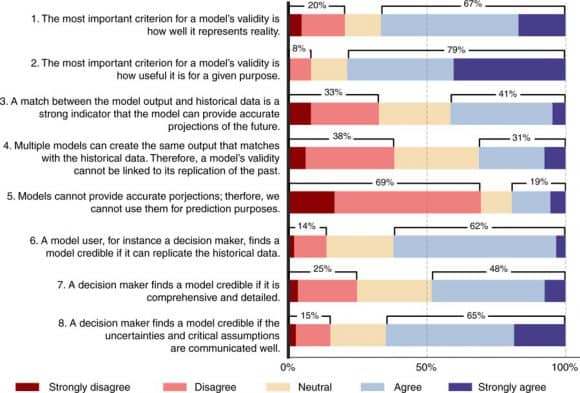

According to our results, published recently in Eker et al. (2018)1, data and prediction are the most prevalent themes in the model validation literature in all main areas of sustainability science such as energy, hydrology and ecosystems. As Figure 1 below shows, the largest fraction of practitioners (41%) think that a match between the past data and model output is a strong indicator of a model’s predictive power (Question 3). Around one third of the respondents disagree that a model is valid if it replicates the past since multiple models can achieve this, while another one third agree (Question 4). A large majority (69%) disagrees with Question 5, that models cannot provide accurate projects, implying that they support using models for prediction purposes. Overall, there is no strong consensus among the practitioners about the role of historical data in model validation. Still, objections to relying on data-oriented validation have not been widely reflected in practice.

Figure 1: Survey responses to the key issues in model validation. Source: Eker et al. (2018)

According to most practitioners who participated in the survey, decision-makers find a model credible if it replicates the historical data (Question 6), and if the assumptions and uncertainties are communicated clearly (Question 8). Therefore, practitioners think that decision makers demand that models match historical data. They also acknowledge the calls for a clear communication of uncertainties and assumptions, which is increasingly considered as best-practice in modeling.

One intriguing finding is that the acknowledgement of uncertainties and assumptions depends on experience level. The practitioners with a very low experience level (0-2 years) or with very long experience (more than 10 years) tend to agree more with the importance of clarifying uncertainties and assumptions. Could it be because a longer engagement in modeling and a longer interaction with decision makers help to acknowledge the necessity of communicating uncertainties and assumptions? Would inexperienced modelers favor uncertainty communication due to their fresh training on the best-practice and their understanding of the methods to deal with uncertainty? Would the employment conditions of modelers play a role in this finding?

As a modeler by myself, I am surprised by the variety of views on validation and their differences from my prior view. With such findings and questions raised, I think this paper can provide model developers and users with reflections on and insights into their practice. It can also facilitate communication in the interface between modelling and decision-making, so that the two parties can elaborate on what makes their models valid and how it can contribute to decision-making.

Model validation is a heated topic that would inevitably stay discordant. Still, one consensus to reach is that a model is a representation of reality, not the reality itself, just like the disclaimer of René Magritte that his perfectly curved and brightly polished pipe is not a pipe.

References

- Eker S, Rovenskaya E, Obersteiner M, Langan S. Practice and perspectives in the validation of resource management models. Nature Communications 2018, 9(1): 5359. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-07811-9 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/15646/]

- EC. Modelling tools for EU analysis. 2019 [cited 16-01-2019]Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/analysis/models_en

- EIA. ANNUAL ENERGY OUTLOOK 2018: US Energy Information Administration; 2018. https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/info_nems_archive.php

- The Economist. In Plato’s cave. The Economist 2009 [cited]Available from: http://www.economist.com/node/12957753#print

- The Economist. Number-crunchers crunched: The uses and abuses of mathematical models. The Economist. 2010. http://www.economist.com/node/15474075

- Stirling A. Keep it complex. Nature 2010, 468(7327): 1029-1031. https://doi.org/10.1038/4681029a

- Nuccitelli D. Climate scientists just debunked deniers’ favorite argument. The Guardian. 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2017/jun/28/climate-scientists-just-debunked-deniers-favorite-argument

- Anscombe N. Models guiding climate policy are ‘dangerously optimistic’. The Guardian 2011 [cited]Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/feb/24/models-climate-policy-optimistic

- Jogalekar A. Climate change models fail to accurately simulate droughts. Scientific American 2013 [cited]Available from: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/the-curious-wavefunction/climate-change-models-fail-to-accurately-simulate-droughts/

- Kruger T, Geden O, Rayner S. Abandon hype in climate models. The Guardian. 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2016/apr/26/abandon-hype-in-climate-models

Oct 5, 2018 | Climate, Climate Change, Ecosystems, Environment, Food, Food & Water, History, Young Scientists

© Marcus Thomson

By Marcus Thomson, researcher, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

While living in Cairo in 2010, I witnessed first-hand the human toll of political and environmental disasters that washed over Africa at the end of the last century. Unprecedented numbers of migrants were pressing into North Africa, many pushed out of their homelands by conflict and state-failure, pulled towards safer, richer, less fragile places like Europe. Throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, climate change was driving up competition for scarce land and water, and raising pressure on farmers to maintain the quantity and quality of their crops.

It is a similar story throughout the developing world, where many farmers do without the use of expensive chemical fertilizer and pesticides, complex irrigation, or boutique seed varieties. They rely instead on traditional land management practices that developed over long periods with consistent, predictable conditions. It is difficult to predict how dryland farmers will respond to climate change; so it is challenging to plan for various social, economic, and political problems expected to develop under, or be exacerbated by, climate change. Will it spur innovation or, as has been argued for the Syrian civil war[1], set up conflict? A major stumbling block is that the dynamics of human social behavior are so difficult to model.

Instead of attempting to predict farmers’ responses to climate change by modelling human behavior, we can look to the responses to environmental changes of farmers from the past as analogues for many subsistence farmers of the future. Methods to fill in historical gaps, and reconstruct the prehistoric record, are valuable because they expand the set of observed cases of societal-scale responses to environmental change. For instance, some 2000 years ago, an expansive maize-growing cultural complex, the Ancestral Puebloans (APs), was well established in the arid American Southwest. By AD 1000, members of this AP complex produced unique and innovative material culture including the famed “Great Houses”, the largest built structures in the United States until the 19th century. However, between AD 1150 and 1350, there was a profound demographic transformation throughout the Southwest linked to climate change. We now know that many APs migrated elsewhere. As a PhD student at the University of California, Los Angeles, I wondered whether a shift to cooler, more variable conditions of the “Little Ice Age” (LIA, roughly AD 1300 to 1850) was linked to the production of their staple crop, maize.

I came to IIASA as a YSSP in 2016 to collaborate with crop modelers on this question, and our work has just been published in the journal Quaternary International.[2] I brought with me high-resolution data from a state-of-the-art climate model to drive the crop simulations, and AP site information collected by archaeologists. Because AP maize was quite different from modern corn, I worked with IIASA soil scientist Juraj Balkovič to modify the crop simulator with parameters derived from heirloom varieties still grown by indigenous peoples in the Southwest. I and IIASA economic geographer Tamás Krisztin developed a statistical technique to analyze the dynamical relationship between AP site occupation and simulated yield outcomes.

We found that for the most climate-stressed high-elevation sites, abandonments were most associated with increased year-to-year yield variability; and for the least stressed low-elevation and well-watered sites, abandonment was more likely due to endogenous stressors, such as soil degradation and population pressure. Crucially, we found that across all regions, populations peaked during periods of the most stable year-to-year crop yields, even though these were also relatively warm and dry periods. In short, we found that AP maize farmers adapted well to gradually rising temperatures and drought, during the MCA, but failed to adapt to increased climate variability after ~AD 1150, during the LIA. Because increased variability is one of the near certainties for dryland farming zones under global warming, the AP experience offers a cautionary example of the limits of low-technology adaptation to climate change, a business-as-usual direction for many sub-Saharan dryland farmers.

This is a lesson from the past that policymakers might take note of.

[1] Kelley, C. P., Mohtadi, S., Cane, M. A., Seager, R., & Kushnir, Y. (2015). Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201421533.

[2] Thomson, M. J., Balkovič, J., Krisztin, T., MacDonald, G. M. (2018). Simulated crop yield for Zea mays for Fremont Ancestral Puebloan sites in Utah between 850-1499 CE based on temperature dailies from a statistically downscaled climate model. Quaternary International. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2018.09.031

Sep 7, 2018 | Brazil, Education, Postdoc

Rafael Morais

Rafael Morais is a recent participant in the IIASA-CAPES Doctorate Sandwich Program, he spent nine months at IIASA working in the Energy program.

In 2016, the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) partnered with IIASA on a new initiative offering support to doctoral and postdoctoral researchers interested in collaborating with established IIASA researchers. As part of this initiative, IIASA and CAPES annually offer up to three fellowships for Brazilian PhD students to spend three to twelve months at IIASA as part of the joint IIASA-CAPES Doctorate Sandwich Program, as well as up to four postdoc fellowships that enable Brazilian researchers to work at IIASA for up to 24 months.

Rafael Morais, a PhD candidate at the Energy Planning Program of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, was part of the first group of Brazilian PhD students funded by CAPES to participate in this program. He spent nine months with the Energy Program at IIASA in 2017. We recently caught up with him and asked him about his research and what the fellowship has meant to him:

What is your PhD research about?

My research involves modeling the contribution of renewable energy sources in electric systems. My doctorate thesis includes a case study on Brazil, where we have large potential for wind and solar power generation in various regions. My main objective is to investigate how total costs develop considering the number of wind and solar plants in the Brazilian electricity system.

Why did you choose IIASA for your doctorate program (over other places)?

I chose IIASA because it is a very reputable think tank for energy and model development. People are very capable and well prepared. They have been working on energy systems modeling for many years, and their experience motivated my decision to come to IIASA. I talked with some people that were at IIASA before me and they were all very grateful for the experience. Another important factor was that it is an international institute, where one can have contact with people from many different countries, and the main language is English.

Rafael Morais

How did your participation in the program benefit you?

I had the opportunity to get into contact with diverse approaches to my research questions, thus enriching my thesis. Unlike my home institution, IIASA does not have only energy experts, but also computer scientists, mathematicians, and physics experts, all working in the same group, and all contributing to a great modeling team. Being here was an excellent opportunity to collaborate with them. As my first experience abroad, it was also a chance for me to grow and develop other skills, both on a professional and a personal level.

Would you recommend that people apply for the IIASA-CAPES doctorate program?

Yes, I would definitely recommend it! IIASA is a very nice place to work. People really care about a harmonious work environment, and IIASA staff are always available to help you with any issue. Apart from that, the people that I worked with during my time here are very knowledgeable and kind. In short, it was a great experience being at IIASA for nine months during my PhD.

Applications for the 2019 IIASA-CAPES Doctorate Sandwich Program and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program opened on 1 September 2018 and will run until 15 October 2018. Candidates have to apply to both CAPES (on the CAPES website) and IIASA. Successful applicants will be informed of the selection results by mid-December 2018. Selected candidates are expected to take up their position at IIASA between March and October 2019.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.