May 26, 2020 | Energy & Climate

Jarmo Kikstra, a research assistant in the IIASA Energy Program, shares his experience at EGU2020: Sharing Geosciences Online.

© Freepik

When our abstract for the 2020 General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union (EGU2020) was accepted, I was very excited as this would be my first scientific conference. EGU2020 was a few weeks ago and took place completely virtually for the first time due to COVID-19. Let’s reflect upon what this experience was like.

As an early career researcher, I was very much looking forward to presenting the research I have worked on for many months. While I had presented preliminary results of this and other research before, both at my university and at my research department, these presentations had been internal or small-scale. EGU2020 was the first time presenting my research to the public, with experts from various fields being able to see the work and provide their input. It felt to me, like a first step into entering the pubic academic debate, an important step into becoming part of a research community.

But clearly, with the ongoing COVID pandemic, the conference was quite different to what I had expected my first conference to be like. EGU2020 became “EGU2020: Sharing Geoscience Online”. With 16,273 scientists participating last year, clearly a big effort took place to move such an event online, and with 26,219 individual online registrations in the online chat system, it seems to have been a success. But of course, not all registrations are equal, and participation numbers are not the only thing that count. So, how was this virtual EGU2020 experience for me?

© Jarmo Kikstra

First, my experience was much shorter than originally envisaged. While this is largely a matter of choice, I, and many other participants, participated in fewer sessions than we would have done during a physical conference. The simple fact of not being ‘out of office’ contributed to me continuing to work on other ongoing tasks for large parts of the week.

However, the chat session and oral presentation session I joined, were surprisingly intense. Many presentations (that would have normally been poster presentations) were discussed in a plenary chat or oral session, and there was little time (~6 min) available for each presentation, meaning that content was very dense, and discussed at breakneck speed. In this way, a snapshot of the current state of research in my field was provided openly with everyone seeing all comments and all presentations in the session. Something that was missing that could have been useful, by complementing the main chat box, were separate channels for each presentation. This could have made follow-up discussions in the chat sessions easier, without interrupting main discussions on the current presentations, and therewith stimulating one of the most important parts of conferences – feedback on the work you have presented.

Proponents of virtual events will argue that doing this will greatly reduce the environmental footprint of science, as (air) travel is the biggest chunk of GHG emissions of many scientists. In fact, a central debate at EGU2020 discussed this topic, and the first question of the Cercedilla Manifesto reads: “Is a physical meeting necessary?”. Opponents however point to the current impossibilities of replacing the benefits of meeting in-person, including higher engagement, getting an academic network, unexpected (group) discussions, social encounters and events, and the possibility for live feedback, etc. Especially for early career scientists, it is often said that attending conferences is very beneficial.

Networking virtually will never be exactly the same as in person, and I don’t think this is something to aim for. Networking can happen in many different formats; however, it is clear to me now that we can still take quite a few steps into increasing the effectiveness of virtual networking during such events. For instance, I did not ‘meet’ new people, whereas that would have surely happened during a physical meeting, even if I would not have actively made an effort. So perhaps when organizers are putting together a virtual event, it may pay off to be creative in providing virtual networking opportunities.

Many argue that an online event is also much more conducive to opening up science, with an enormous potential for increasing the accessibility to science and scientific discussions and stimulating the development of knowledge. The great success of EGU2020 is probably already in its name: “Sharing Geoscience Online”. On the EGU2020 website you can find thousands of presentations, on all topics that are related to geosciences, with many contributions from IIASA. In other words, a lot of research content has been uploaded to one place, open to everyone; thereby turning this scientific event into a great resource for sharing, learning, asking questions and providing feedback. Discussions on this platform will be ongoing until the end of the month. So, take advantage of this opportunity and have a look!

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 28, 2020 | Air Pollution, Alumni, India, Poverty & Equity, Young Scientists

By Abhishek Kar, Postdoctoral Research Scientist at Columbia University, USA, and IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) alumnus.

Abhishek Kar shares his thoughts on the Indian government’s Ujjwala program, which aims to scale up household access to Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) for clean cooking.

© Kaiskynet | Dreamstime.com

About 2.9 billion people depend on burning traditional fuels like firewood rather than modern cooking fuels like gas and electricity to cook their daily meals. The household air pollution caused when these fuels are burned, along with the resultant exposure to kitchen smoke causes several respiratory and other diseases. It is estimated that between 2 and 3.6 million people die every year due to lack of access to clean cooking fuels. It also has severe environmental effects like forest degradation and contributes to climate change. To address these challenges, the Indian Government launched a massive program called Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY, or Ujjwala) to scale up household access to Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) in May 2016.

My IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) project under Shonali Pachauri’s supervision was about analyzing consumption patterns of LPG in rural India. We looked at whether there was any differences in consumption patterns between the Ujjwala beneficiaries and general consumers. The analysis formed part of my PhD research and was eventually published as the cover story for the September 2019 issue of the journal, Nature Energy. The journal also invited us to write a policy brief, which was published in January 2020. The study’s findings received widespread media attention, especially in India. When I talk to journalists, they often ask whether the Ujjwala program is a success or a failure. I would like to use this opportunity to clear common misconceptions and share my thoughts.

The Ujjwala program’s original mandate was to tackle the challenge of “lack of access to clean fuel” and to make LPG affordable for poor women. The program provided capital subsidies to this end. Unfortunately, the policy document neither discussed usage of LPG as an exclusive or primary cooking fuel, nor did it provide any incentive for regular use (barring the universal LPG cylinder subsidy that is provided to everyone). The program was ambitious in terms of both scale and timeline, and fulfilled its original aim of providing LPG connections for millions of poor women.

Current debates around the program’s failure to result in smokeless kitchens are happening only because Ujjwala succeeded in fulfilling its original mandate of ensuring physical access. In my opinion, it is truly a remarkable achievement to have reached out to 80 million poor women within 40 months. The process not only involved massive awareness generation and community mobilization, but also ramping up the supply chain to meet increased demand. While I have a lot to say about how Ujjwala can be improved, I think it would be unfair to call it a failure. Access is the first step towards transition to clean fuels, and at least in this respect, it was an extraordinary success, making it a model of energy access for developing countries.

Our research shows that Ujjwala was able to attract new consumers rapidly, but those consumers did not start using LPG on a regular basis. Based on the literature and my own experience, there are five reasons why regular LPG use is a challenge for Ujjwala consumers, and the scheme did not have any specific provisions to effectively address them.

First, rural communities generally have easy access to free firewood, crop residues, cattle dung, etc. So why would they start paying for commercial fuel, when free fuel is readily available for cooking?

Secondly, Ujjwala (bravely) targeted poor women, who generally have limited disposable cash and seasonal, agriculture linked fluctuations in income. If there is no additional income, what costs would a poor family on an already tight budget have to cut to afford such a regular additional expense? While the program has made a 5 kg cylinder option available in response to this issue, the impact on LPG sales is still unknown.

Thirdly, home delivery of LPG cylinders is a challenge in most rural areas, as the cost of delivery for LPG distributors often outweighs the commission they receive. If there is no delivery option, poor rural families who often don’t have access to transport would need to arrange for a cylinder to be picked up from a far-off retail outlet. Oil Marketing Companies have vigorously been pushing for home delivery, but unless there are explicit incentives for this, the situation is unlikely to improve.

© Dmitrii Melnikov | Dreamstime.com

In the fourth place, gender dynamics make the situation even more complicated. Men are often financial decision makers who have to make budget cuts, while women are the primary beneficiaries of LPG in terms of a quick and smokeless cooking experience, with the side benefit of avoiding the drudgery of fuelwood collection. The laudable effort of the LPG panchayat platform, where women share their success stories and strategies to overcome opposition within their homes, is a step in the right direction, but it is unlikely that this will be sufficient to tackle a deep-rooted societal problem.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, people will have to stop using mud stoves and start using LPG stoves, which may involve real (or, perceived) changes in the taste, texture, look, and size of food items. As a student of habit change literature, I am surprised that anyone expected that such a switch would not be accompanied by behavior change interventions.

Ultimately, the Ujjwala scheme provided incentives to reduce the burden of the capital cost of LPG connections, and poor female consumers responded to it positively. This is a successful first step towards clean cooking energy transition. However, there were no scheme incentives to promote use, except general LPG subsidies, which is available to all, including the urban middle class. Consumers simply decided that the transition to LPG through regular purchase of LPG refills was not worth it, and did not take the next step. I would however not call this a failure of Ujjwala, as that was never the original program objective.

We have to acknowledge that Ujjwala’s phenomenal success in providing access to clean fuel has put the spotlight on its ineffectiveness to ensure sustained regular use. If you ask me, this is a classic case of the glass half-full or half-empty scenario. Or, as my PhD supervisor at the University of British Columbia, Hisham Zerrifi, puts it: “It depends!”

References:

[1] Kar A, Pachauri S, Bailis R, & Zerriffi H (2019). Using sales data to assess cooking gas adoption and the impact of India’s Ujjwala program in rural Karnataka. Nature Energy DOI: 10.1038/s41560-019-0429-8 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15994]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 14, 2020 | China, Environment, Food & Water, Water, Women in Science

By Maryna Strokal, Department of Environmental Sciences, Water Systems and Global Change, Wageningen University and Research, The Netherlands

Maryna Strokal discusses a new integrated approach to finding cost-effective solutions for nutrient pollution and coastal eutrophication developed with IIASA colleagues.

© Huy Thoai | Dreamstime.com

Have you ever wondered why the water in some rivers appear to be green? The green tinge you see is due to eutrophication, which means that too many nutrients – specifically nitrogen and phosphorus – are present in the water. This happens because rivers receive these nutrients from various land-based activities like run-off from agricultural fields and sewage effluents from cities. Rivers in turn export many of these nutrients to coastal waters, where it serves as food for algae. Too many nutrients, however, cause the algae and their blooms to grow more than normal. Because algae consumes a lot of oxygen, this lowers the available oxygen supply in the water, killing off fish and other marine life. Some algae can also be toxic to people when they eat seafood that have been exposed to, or fed on it. Polluted river water on the other hand, is unfit for direct use as drinking water, or for cooking, showering, or any of our other daily needs. Before we can use this water, it needs to be treated, which of course costs money.

To better understand and address these issues, I worked with colleagues from IIASA, Wageningen University, and China to develop an integrated approach to identify cost-effective solutions (read cheapest) to reduce river pollution and thus coastal eutrophication. Our integrated approach takes into account human activities on land, land use, the economy, the climate, and hydrology. We implemented the new approach for the Yangtze Basin in China.

The Yangtze is the third longest river in the world and exports nutrients from ten sub-basins to the East China Sea, where the coast often experiences severe eutrophication problems that may increase in the coming years. The Chinese government has called for effective actions to ensure clean water for both people and nature.

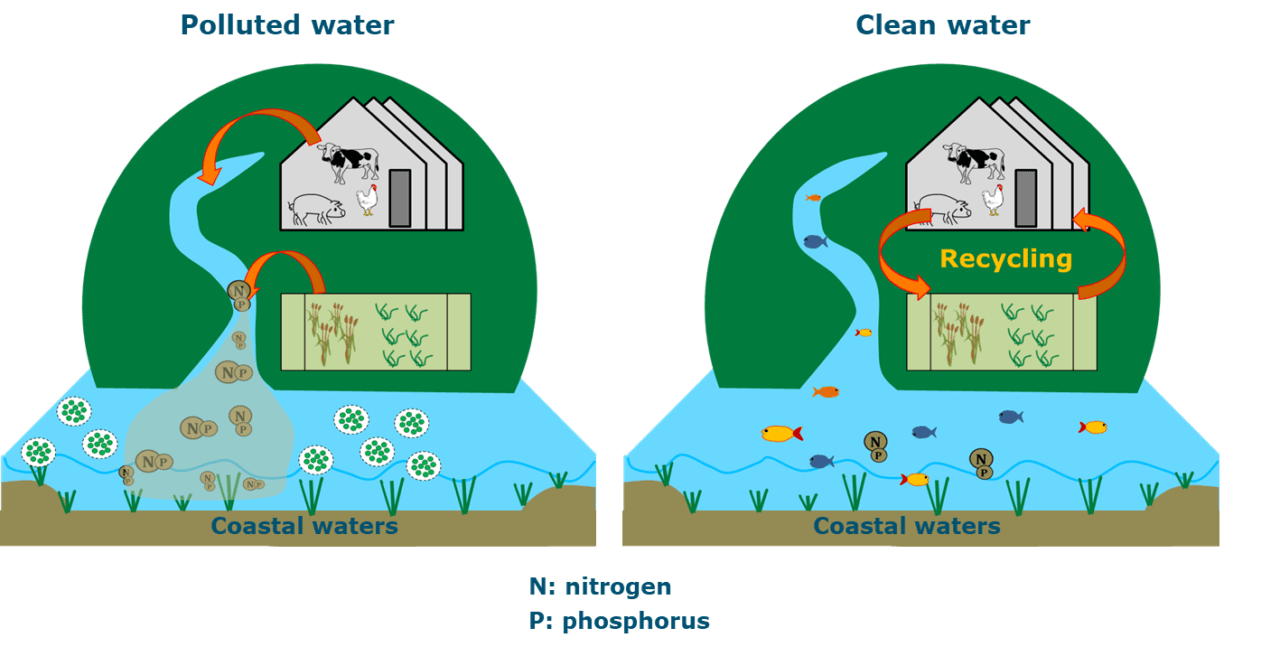

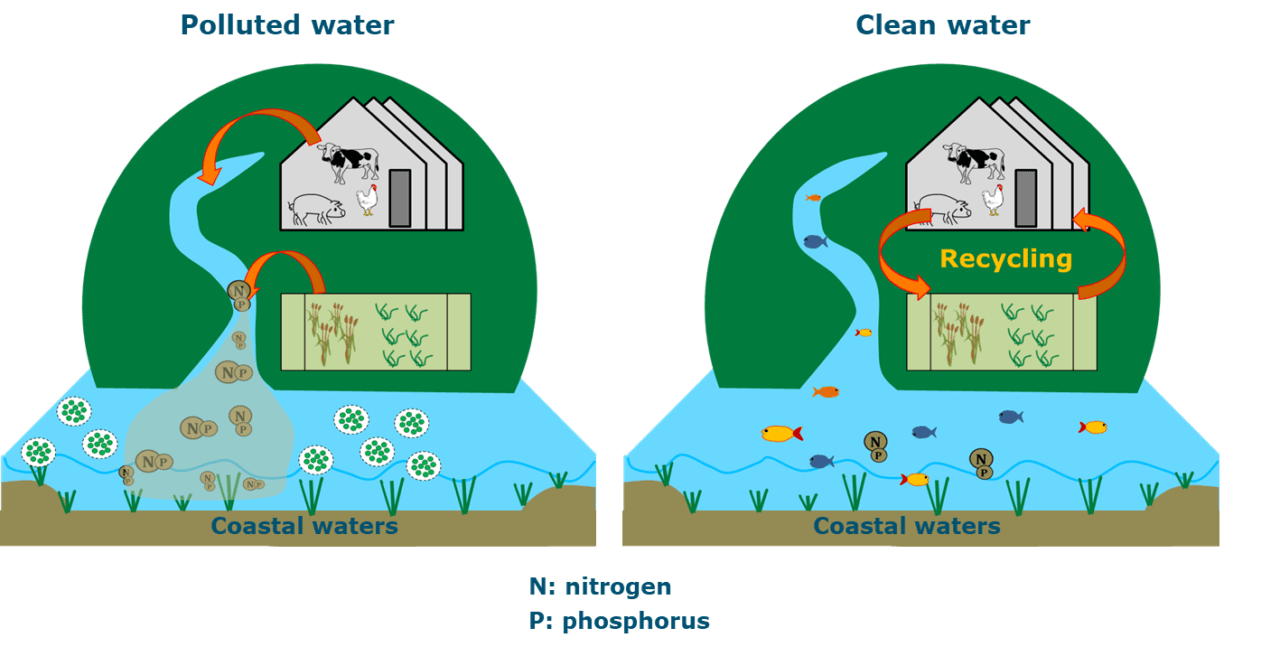

In our paper on this work, which was recently published in the journal Resources, Conservation, and Recycling, my colleagues and I conclude that reducing more than 80% of nutrient pollution in the Yangtze will cost US$ 1–3 billion in 2050. This cost might seem high, but it is actually far below 10% of the income level in the Yangtze basin. We also identified an opportunity in the negative or zero cost range, which would result in a below 80% reduction in nutrient export by the Yangtze. This negative or zero cost alternative involves options to recycle manure on land and reduce the use of chemical fertilizers (Figure 1). More recycling means that farmers will buy less chemical fertilizers and potential savings can then compensate for the expenses related to recycling the manure. We also illustrated the costs that would be involved for ten sub-basins to reduce their nutrient export to coastal waters.

Figure 1. Summarized illustration of eutrophication causes and cost-effective solutions for reducing nutrient export by Yangtze and thus coastal eutrophication in the East China Sea in 2050.

Recycling manure on cropland is an important and cost-effective solution for agriculture in the sub-basins of the Yangtze River (Figure 1). Manure is rich in the nutrients that crops need, and opting for this alternative instead of chemical fertilizers avoids loss of nutrients to rivers, and thus ultimately to coastal waters. Current practices are however still far from ideal, with manure – and especially liquid manure – often being discharged into water because crop and livestock farms are far away from each other, which makes it practically and economically difficult to transport manure to where it is needed. Another reason is the historical practice of farmers using chemical fertilizers on their crops – it is simply how they are used to doing things. Unfortunately, the amounts of fertilizers that farmers apply are often far above what crops actually need, thus leading to river pollution.

The Chinese government are investing in combining crop and livestock production, in other words, they are creating an agricultural sector where crops are used to feed animals and manure from the animals is in turn used to fertilize crops. Chinese scientists are working with farmers to implement these solutions.

In our paper, we showed that these solutions are not only sustainable, but also cost-effective in terms of avoiding coastal eutrophication. We invite you to read our paper for more details.

References

Strokal M, Kahil T, Wada Y, Albiac J, Bai Z, Ermolieva T, Langan S, Ma L, et al. (2020). Cost-effective management of coastal eutrophication: A case study for the Yangtze River basin. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 154: e104635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104635.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 5, 2020 | Alumni, Climate Change, Science and Policy, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Leila Niamir, post-doctoral researcher at the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), Germany and IIASA YSSP alumna.

© Cienpies Design Illustrations | Dreamstime

Weather patterns and events are changing and becoming more extreme, sea levels are rising, and greenhouse gas emissions are now at their highest levels in history[1]. Climate change is affecting every individual in every city on every continent. It imposes adverse impact on people, communities, and countries, disrupting regional and national economies.

Climate change mitigation refers to efforts to reduce or prevent emissions of greenhouse gases to limit the magnitude of long-term climate change. Human consumption, in combination with a growing population, contributes to climate change by increasing the rate of greenhouse gas emissions. Over the last decade, instigated by the Paris Agreement, the efforts to limit global warming have been expanding. Significant attention is being devoted to new energy technologies on both the production and consumption sides, however, changes in individual behavior and management practices as part of the mitigation strategy are often neglected[2]. This might derive from the complex nature of human which makes explaining and affecting human behavior a difficult task. As a result, quantitative tools to assess household emissions, considering the diversity of behaviors and a variety of psychological and social factors influencing them beyond purely economic considerations, are scarce. Policymakers would benefit from reliable decision supporting tools that explore the interaction of economic decision-making and behavioral heterogeneity in households behavioral and lifestyle changes, when testing climate mitigation policies (e.g. carbon pricing, subsidies)[3].

To address this issue, during my PhD research I studied the potential of behavioral changes among heterogeneous households regarding energy use and their role in mitigating climate change. By designing and conducting comprehensive household surveys, it was explored how individuals choose to change their energy behaviour and what factors trigger or inhibit these choices[4]. Decision support tools are designed to study large-scale regional effects of individual actions, and to explore how they may change over time and space. The model explicitly treats behavioral triggers and barriers at the individual level, assuming that energy use decision making is a multi-stage process. This theoretically and empirically grounded simulation model offers policymakers ways to explore various policy portfolios by running diverse micro and macro scenarios.

This model was further developed during my collaboration with the IIASA the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), to estimate macro impacts of individuals’ energy behavioral changes on carbon emissions[5]. Within this research, we illustrate that individual energy behavior, especially when amplified through social context, shapes energy demand and, consequently, carbon emissions. Our results show that residential energy demand is strongly linked to personal and social norms. When assessing the cumulative impacts of these behavioral processes, we quantify individual and combined effects of social dynamics and of carbon pricing on individual energy efficiency and on the aggregated regional energy demand and emissions.

In summary, mitigating climate change requires massive worldwide efforts and strong involvement of regions, cities, businesses and individuals, in addition to the commitments at the national levels. We should always keep in mind that every single behavior matters. In the transition to a sustainable and resilient society, we –as individuals- are more than just consumers.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

[1] Climate Action– United Nations Sustainable Development Goals https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change/

[2] Creutzig, F., et al. (2018). Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nature Climate Change 8, 268-271; Grubler, A., et al. (2018). A low energy demand scenario for meeting the 1.5 degrees C target and sustainable development goals without negative emission technologies. Nature Energy 3, 515-527; Creutzig, F., et al. (2016). Beyond Technology: Demand-Side Solutions for Climate Change Mitigation. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, Vol 41 41, 173-198

[3] Niamir, L. (2019). Behavioural Climate Change Mitigation: from individual energy choices to demand-side potential (University of Twente); Creutzig, F., et al. (2018). Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nature Climate Change 8, 268-271; Niamir, L., et al. (2018). Transition to low-carbon economy: Assessing cumulative impacts of individual behavioural changes. Energy Policy, 118; Stern N. Economics: Current climate models are grossly misleading. Nature 530(7591):407–9.

[4] Niamir, L. et al. (2020). Demand-side solutions for climate mitigation: Bottom-up drivers of household energy behaviour change in the Netherlands and Spain. Energy Research & Social Science, 62, 101356.

[5] The results of this collaboration was presented at Impacts World 2017 and won the best prize, and also published at Climatic Change Journal.

Nov 21, 2019 | Air Pollution, Environment, Food & Water, Indonesia, Women in Science

By Adriana Gómez-Sanabria, researcher in the IIASA Air Quality and Greenhouse Gases Program

Adriana Gómez-Sanabria discusses the results of a new study that looked into the impacts of implementing various technologies to treat wastewater from the fish processing industry in Indonesia.

© Mikhail Dudarev | Dreamstime.com

To reduce water pollution and climate risks, the world needs to go beyond signing agreements and start acting. Translating agreements and policies into action is however always much more difficult than it might seem, because it requires all players involved to participate. A complete integration strategy across all sectors is needed. One of the advantages of integrating all sectors is that it would be possible to meet different objectives, for example, climate and water protection goals in this case, with the same strategy.

I was involved in a study that assessed the impacts of implementing various technologies to treat wastewater from the fish processing industry in Indonesia when involving different levels of governance. This study is part of the strategies that the government of Indonesia is evaluating to meet the greenhouse gas mitigation goals pledged in its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), as well as to reduce water pollution. Although Indonesia has severe national wastewater regulations, especially in the fish processing industry, these are not being strictly implemented due to lack of expertise, wastewater infrastructure, budgetary availability, and lack of stakeholder engagement. The objective of the study was to evaluate which technology would be the most appropriate and what levels of governance would need to be involved to simultaneously meet national climate and water quality targets in the country.

Seven different wastewater treatment technologies and governance levels were included in the analysis. The combinations included were: 1) Untreated/anaerobic lagoons – where untreated means wastewater is discharged without any treatment and anaerobic lagoons are ponds filled with wastewater that undergo anaerobic processes – combined with the current level of governance. 2) Aeration lagoons – which are wastewater treatment systems consisting of a pond with artificial aeration to promote the oxidation of wastewaters, plus activated sludge focused solely on water quality targets with no coordination between water and climate institutions. 3) Swimbed, which is an aerobic aeration tank focusing mainly on climate targets assuming no coordination between institutions. 4) Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) technology, which is an anaerobic reactor with gas recovery and use followed by Swimbed, and 5) UASB with gas recovery and use followed by activated sludge, which is an aerobic treatment that uses microorganisms forming particles that clump together. Both, 4 and 5 assume vertical and horizontal coordination between water and climate institutions at national, regional, and local level. It is important to notice that the main difference between 4 and 5 is the technology used in the second step. Two additional combinations, 6 and 7, are also proposed including the same technological combinations of 4 and 5, but these include increasing the level of governance to a multi-actor coordination level. The multi-actor level includes coordination at all institutional levels but also involves academia, research institutes, international support, and other stakeholders.

Our results indicate that if the current situation continues, there would be an increase of greenhouse gases and water pollution between 2015 and 2030, driven by the growth in fish industry production volumes. Interestingly, the study also shows that focusing only on strengthening capacities to enforce national water policies would result in greenhouse gas emissions five times higher in 2030 than if the current situation continues, due to the increased electricity consumption and sludge production from the wastewater treatment process. The benefit of this strategy would be positive for the reduction of water pollution, but negative for climate change mitigation. From our analyses of combinations 2 and 3 we learned that technology can be very efficient for one purpose but detrimental for others. If different institutions are, for example, responsible for water quality and climate change mitigation, communication between the institutions is crucial to avoid trade-offs between environmental objectives.

Furthermore, when analyzing different cooperation strategies together with a combination of diverse sets of technologies, we found that not all combinations work appropriately. For instance, improving interaction just within and between institutions does not guarantee proper selection and application of technologies. In this case, the adoption of the technology is not fast enough to meet the targets proposed in 2030, thus resulting in policy implementation failures. Our analyses of combinations 4 and 5 showed that interaction within and between national, regional, and local institutions alone is not enough to prevent policy failure.

Finally, a multi-actor cooperation strategy that includes cooperation across sectors, administrative levels, international support, and stakeholders, seems to be the right approach to ensure selection of the most appropriate technologies and achieve policy success. We identified that with this approach, it would be possible to reduce water pollution and simultaneously decrease greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity required for wastewater treatment. Analyzing combinations 6 and 7 revealed that multi-actor governance allows to simultaneously meet climate and water objectives and a high chance to prevent policy failure.

In the end, analyses such as the one shown here, highlight the importance of integrating and creating synergies across sectors, administrative levels, stakeholders, and international institutions to ensure an effective implementation of policies that provide incentives to make careful choices regarding multi-objective treatment technologies.

Reference:

Gómez-Sanabria A, Zusman E, Höglund-Isaksson L, Klimont Z, Lee S-Y, Akahoshi K, Farzaneh H, & Chairunnisa (2019). Sustainable wastewater management in Indonesia’s fish processing industry: bringing governance into scenario analysis. Journal of Environmental Management (Submitted).

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.