Sep 23, 2019 | Ecosystems, Environment, Sustainable Development

By Frank Sperling, Senior Project Manager (FABLE) in the IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Food and land use systems play a critical role in managing climate risks and bringing the world onto a sustainable development trajectory.

The UN Secretary General’s Climate Action Summit in New York on 23 September seeks to catalyze further momentum for climate change mitigation and adaptation. The transformation of the food and land use system will play a critical role in managing climate risks and bringing the world onto a sustainable development trajectory.

Today’s food and land use systems are confronted with a great variety of challenges. This includes delivering on universal food security and better diets by 2030. Over the last decades, great strides have been made towards achieving universal food security, but this progress recently grinded to a halt. The number of people suffering from chronic hunger has been rising again from below 800 million in 2015 to over 820 million people today [1]. Food security is however not only about a sufficient supply of calories per person. It is also about improving diets, addressing the worldwide increase in the prevalence of obesity, and how we use and value environmental goods and services.

© Paulus Rusyanto | Dreamstime.com

Agriculture, forestry and other land use currently account for around 24% of greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activities [2]. Land use changes are also a major driver behind the worldwide loss of biodiversity [3]. Clearly, in light of population growth and the increasingly visible fingerprints of a human-induced global climate crisis and other environmental changes, business as usual is not an option.

Systems thinking is key in shifting towards more sustainable practices. A new report released by the Food and Land-Use System (FOLU) Coalition showcases that there is much to be gained. There are massive hidden costs in our current food and land use systems. The report outlines ten critical transitions, which can substantially reduce these hidden costs, thereby generating an economic prize, while improving human and planetary health.

The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) contributed to the analytics underpinning the report [4], applying the Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM) [5]. A “better futures” scenario, which seeks to collectively address development and environmental objectives, was compared to a “current trends” scenario, which is basically a continuation of a business-as-usual scenario. The assessment illustrates that an integrated approach that acknowledges the interactions in the food and land use space, can help identify synergies and manage trade-offs across sectors. For example, shifting towards healthy diets not only improves human health, but also reduces pressure on land, thereby helping to improve the solution space for addressing climate change and halting biodiversity loss.

While understanding that the global picture is important, practical solutions require engagement with national and subnational governments. The challenge is to identify development pathways that address the development needs and aspirations of countries within global sustainability contexts. As part of FOLU, the Food, Agriculture, Biodiversity, Land and Energy (FABLE) Consortium was initiated to do exactly this. The FABLE Secretariat, jointly hosted by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) and IIASA, is working with knowledge institutions from developed and developing countries, to explore the interactions between national and global level objectives and their implications for pathways towards sustainable food and land use systems. Preliminary results from inter-active scenario and development planning exercises, so-called Scenathons, were recently presented in the FABLE 2019 report.

These initiatives highlight that acknowledging and embracing complexity can help reconcile development and environmental interests. This also entails rethinking how we relate to and manage nature’s services and their role in providing the foundation for the welfare of current and future generations. This is underscored by the prominent role nature-based solutions are given at the UN Secretary General’s Climate Action Summit. We need to move from silo-based, sector specific, single objective approaches to a focus on multiple objective solutions. In the land use space, this means embedding agriculture in the broader land use context, which accounts for and values environmental services, and linking to the food system where dietary choices shape human health and the demand for land.

Doing so will help bridge the international policy objectives of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the UN Convention on Combating Desertification (UNCCD), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) enshrined in ‘The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’. This represents an opportunity to create a new value proposition for agriculture and other land use activities where environmental stewardship is rewarded.

References

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) et al. (2019). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019. Safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns. Rome, FAO.

[2] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2019). Climate Change and Land. IPCC Special Report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

[3] Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (2018). The IPBES assessment report on land degradation and restoration. Montanarella, L., Scholes, R., and Brainich, A. (eds.). Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, Germany. 744 pages.

[4] Deppermann, A. et al. 2019. Towards sustainable food and land-use systems: Insights from integrated scenarios of the Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM). Supplemental Paper to The 2019 Global Consultation Report of the Food and Land Use Coalition Growing Better: Ten Critical Transitions to Transform Food and Land Use. Laxenburg, IIASA.

[5] Havlik P, Valin H, Herrero M, Obersteiner M, Schmid E, Rufino MC, Mosnier A, Thornton PK, et al. (2014). Climate change mitigation through livestock system transitions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (10): 3709-3714. DOI: 1073/pnas.1308044111 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/10970].

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 17, 2019 | Alumni, IIASA Network

Monika Bauer, IIASA Network and Alumni Officer, interviewed alumnus Dennis Meadows during his recent visit to IIASA.

Dennis Meadows with colleagues in the IIASA Water & RISK Programs © Monika Bauer | IIASA

“It’s a great pleasure to be back at IIASA because the institute really had a big impact on my professional life,” said Dennis Meadows, coauthor of the seminal book Limits to Growth, after his lecture to IIASA staff during a recent visit to the institute. “I came to IIASA, and it gave me so many new ideas and contacts. It became the fuel for my professional activities for a long time.”

Meadows visited the IIASA Energy Program in 1977 when Roger Levien was director, and he says that Levien greatly impacted the way he viewed problems. In his lecture titled, Lessons from 50 years of model-based policy advocacy, he pointed out that Levien looked at problems as universal or global, and that he uses the criteria Levien passed on to him in what he calls “problem selection” to this day. Meadows also spent some time at the institute from 1983-1984 when C.S. Buzz Holling was director.

During his lecture, Meadows highlighted the idea of using the concept of an “invisible college” as a strategy to implement academic work. He explained that an “invisible college” usually constitutes a group of about 50 people connected with an issue, who, while they do not necessarily all have to agree on the issue or do the same work, can collectively come up with a solution.

© Dennis Meadows

Meadows created his version of an invisible college through the Balaton Group, a global network for collaboration on systems and sustainability that he founded in 1982. He says that the network is meant to “connect and empower people who will go back home and do good things”. Meadows stopped by IIASA on his way to the group’s annual retreat in at Lake Belaton in Hungary, where 50 leading scientists, teachers, consultants, writers, and managers annually get together to discuss topical issues on their own costs. According to Meadows, this in itself shows the value individuals see in the meetings. The results of past meetings are outlined on the group’s webpage.

When asked about his key messages for IIASA, Meadows’ answers focused on the institute’s alumni network and exploring a deeper understanding of resilience.

“The incredible power of IIASA lies in its alumni, rather than in its models. You create the alumni network through the process of creating models. IIASA doesn’t have many models, but it has thousands of alumni. One of the first things I would look at is how to link alumni more strongly together, so they could help each other. I still have affection for the institute and respect for what it does, and I’m sure that my opinion is shared by many.”

His second take-away for IIASA concerns building a deeper expertise on resilience. “Sustainable development is something that is hard to realize, while there is no doubt that shocks will continue to occur, and there is no unified theory in resilience yet. In my opinion, IIASA has an opportunity to tap into a huge legacy of understanding that goes back to Buzz Holling’s work.”

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 24, 2019 | Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Sustainable Development

By Pallav Purohit, researcher with the IIASA Air Quality and Greenhouse Gases Program

More than 300 million people in Hindu Kush Himalaya-countries still lack basic access to electricity. Pallav Purohit writes about recent research that looked into how the issue of energy poverty in the region can be addressed.

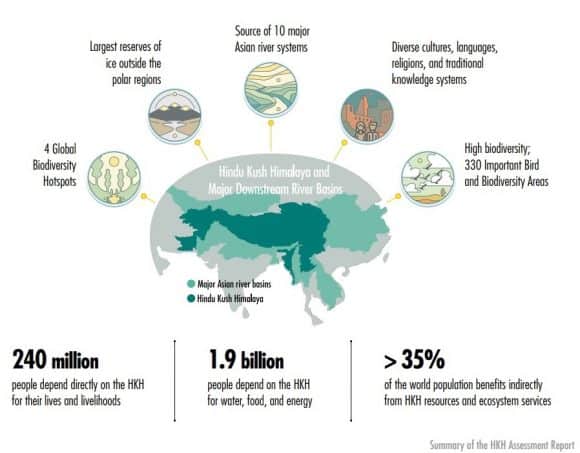

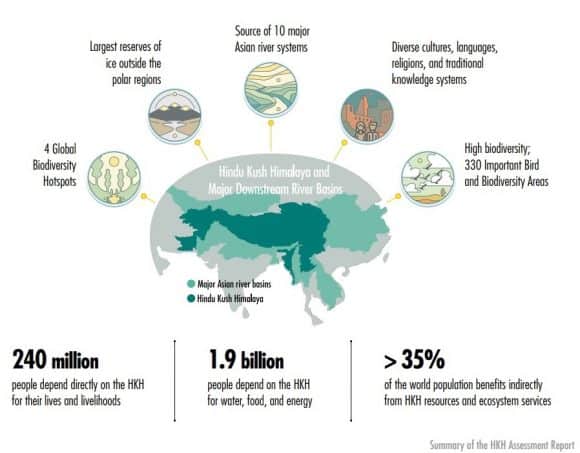

The Hindu Kush Himalayas is one of the largest mountain systems in the world, covering 4.2 million km2 across eight countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan. The region is home to the world’s highest peaks, unique cultures, diverse flora and fauna, and a vast reserve of natural resources.

Ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all – the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 – has however been especially elusive in this region, where energy poverty is shockingly high. About 80% of the population don’t have access to clean energy and depend on biomass – mostly fuelwood – for both cooking and heating. In fact, over 300 million people in Hindu Kush Himalaya-countries still lack basic access to electricity, while vast hydropower potentials remain largely untapped. Although a large percentage of these energy deprived populations live in rural mountain areas that fall far behind the national access rates, mountain-specific energy access data that reflects the realities of mountain energy poverty barely exists.

Source: Wester et al. (2019)

The big challenge in this regard is to simultaneously address the issues of energy poverty, energy security, and climate change while attaining multiple SDGs. The growing sectoral interdependencies in energy, climate, water, and food make it crucial for policymakers to understand cross-sectoral policy linkages and their effects at multiple scales. In our research, we critically examined the diverse aspects of the energy outlook of the Hindu Kush Himalayas, including demand-and-supply patterns; national policies, programmes, and institutions; emerging challenges and opportunities; and possible transformational pathways for sustainable energy.

Our recently published results show that the region can attain energy security by tapping into the full potential of hydropower and other renewables. Success, however, will critically depend on removing policy-, institutional-, financial-, and capacity barriers that now perpetuate energy poverty and vulnerability in mountain communities. Measures to enhance energy supply have had less than satisfactory results because of low prioritization and a failure to address the challenges of remoteness and fragility, while inadequate data and analyses are a major barrier to designing context specific interventions.

In the majority of Hindu Kush Himalaya-countries, existing national policy frameworks currently primarily focus on electrification for household lighting, with limited attention paid to energy for clean cooking and heating. A coherent mountain-specific policy framework therefore needs to be well integrated in national development strategies and translated into action. Quantitative targets and quality specifications of alternative energy options based on an explicit recognition of the full costs and benefits of each option, should be the basis for designing policies and prioritizing actions and investments. In this regard, a high-level, empowered, regional mechanism should be established to strengthen regional energy trade and cooperation, with a focus on prioritizing the use of locally available energy resources.

© Kriangkraiwut Boonlom | Dreamstime.com

Some countries in the region have scaled up off-grid initiatives that are globally recognized as successful. We however found that the special challenges faced by mountain communities – especially in terms of economies of scale, inaccessibility, fragility, marginality, access to infrastructure and resources, poverty levels, and capability gaps – thwart the large-scale replication of several best practice innovative business models and off-grid renewable energy solutions that are making inroads into some Hindu Kush Himalayan countries.

This further highlights an urgent need to establish supportive policy, legal, and institutional frameworks as well as innovations in mountain-specific technology and financing. In addition, enhanced multi-stakeholder capacity building at all levels will be needed for the upscaling of successful energy programs in off-grid mountain areas.

Finally, it is important to note that sustainable energy transition is a shared responsibility. To accelerate progress and make it meaningful, all key stakeholders must work together towards a sustainable energy transition. The world needs to engage with the Hindu Kush Himalayas to define an ambitious new energy vision: one that involves building an inclusive green society and economy, with mountain communities enjoying modern, affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy to improve their lives and the environment.

References:

[1] Dhakal S, Srivastava L, Sharma B, Palit D, Mainali B, Nepal R, Purohit P, Goswami A, et al. (2019). Meeting Future Energy Needs in the Hindu Kush Himalaya. In: The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment. pp. 167-207 Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15666]

[2] Wester P, Mishra A, Mukherji A, Shrestha AB (2019). The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 2, 2018 | Alumni, Economics, IIASA Network, Science and Policy

W. Brian Arthur from the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), and a former IIASA researcher, talks about increasing returns and the magic formula to get really great science.

Recently, Brian stopped in at the Complexity Science Hub Vienna, of which IIASA is a member institution, and spoke to Verena Ahne about his work.

Brian Arthur (© Complexity Science Hub)

Brian, now 71, is one of the most influential early thinkers of the SFI, a place that without exaggeration could be called the cradle of complexity science.

Brian became famous with his theory of increasing returns. An idea that has been developed in Vienna, by the way, where Brian was part of a theoretical group at the IIASA in the early days of his career: from 1978 to 1982.

“I was very lucky,” he recalls. “I was allowed to work on what I wanted, so I worked on increasing returns.”

The paper he wrote at that time introduced the concept of positive feedbacks into economy.

The concept of “increasing returns”

Increasing returns are the tendency for that which is ahead to get further ahead, for that which loses advantage to lose further advantage. They are mechanisms of positive feedback that operate—within markets, businesses, and industries—to reinforce that which gains success or aggravate that which suffers loss. Increasing returns generate not equilibrium but instability: If a product or a company or a technology—one of many competing in a market—gets ahead by chance or clever strategy, increasing returns can magnify this advantage, and the product or company or technology can go on to lock in the market.”

(W Brian Arthur, Harvard Business Review 1996)

This was a slap in the face of orthodox theories which saw–and some still see–economy in a state of equilibrium. “Kind of like a spiders web,” Brian explains me in our short conversation last Friday, “each part of the economy holding the others in an equalization of forces.”

The answer to heresy in science is that it does not get published. Brian’s article was turned down for six years. Today it counts more than 10.000 citations.

At the latest it was the development and triumphant advance of Silicon Valley’s tech firms that proved the concept true. “In fact, that’s now the way how Silicon Valley runs,” Brian says.

The youngest man on a Stanford chair

William Brian Arthur is Irish. He was born and raised in Belfast and first studied in England. But soon he moved to the US. After the PhD and his five years in Vienna he returned to California where he became the youngest chair holder in Stanford with 37 years.

Five years later he changed again – to Santa Fe, to an institute that had been set up around 1983 but had been quite quiet so far.

Q: From one of the most prestigious universities in the world to an unknown little place in the desert. Why did you do that?

A: In 1987 Kenneth Arrow, an economics Nobel Prize winner and mentor of mine, said to me at Stanford: We’re holding a small conference in September in a place in the Rockies, in Santa Fe, would you go?

When a Nobel Prize winner asks you such a question, you say yes of course. So I went to Santa Fe.

We were about ten scientists and ten economists at that conference, all chosen by Nobel Prize winners. We talked about the economy as an evolving complex system.

Veni, vidi, vici

Brian came – and stayed: The unorthodox ideas discussed at the meeting and the “wild” and free atmosphere of thinking at “the Institute”, as he calls the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), thrilled him right away.

In 1988 Brian dared to leave Stanford and started to set up the first research program at Santa Fe. Subject was the economy treated as a complex system.

Q: What was so special about SF?

A: The idea of complexity was quite new at that time. But people began to see certain patterns in all sorts of fields, whether it was chemistry or the economy or parts of physics, that interacting elements would together create these patterns…To investigate this in universities with their particular disciplines, with their fixed theories, fixed orthodoxies–where it is all fixed how to do things–turned out to be difficult.

Take the economy for example. Until then people thought it was in an equilibrium. And there we came and proved, no, economics is no equilibrium! The Stanford department would immediately say: You can’t do that! Don’t do that! Or they would consider you to be very eccentric…

So a bunch of senior fellows at Los Alamos in the 1980s thought it would be a good idea if there was an independent institute to research these common questions that came to be called complexity.

At Santa Fe you could talk about any science and any basic assumptions you wanted without anybody saying you couldn’t or shouldn’t do that.

Our group as the first there set a lot of this wild style of research. There were lots of discussions, lots of open questions, without particular disciplines… In the beginning there were no students, there was no teaching. It was all very free.

This wild style became more or less the pattern that has been followed ever since. I think the Hub is following this model too.

The magic formula for excellence

Q: Was this just a lucky concurrence: the right people and atmosphere at the right time? Or is there a pattern behind it that possibly could be repeated?

A: I am sure: If you want to do interdisciplinary science – which complexity is: It is a different way of looking at things! – you need an atmosphere where people aren’t reinforced into all the assumptions of the different disciplines.

This freedom is crucial to excellent science altogether. It worked out not only for Santa Fe. Take the Rand Corporation for instance, that invented a lot of things including the architecture of the internet, or the Bell Labs in the Fifties that invented the transistor. The Cavendish Lab in Cambridge is another one, with the DNA or nuclear astronomy…

The magic formula seems to be this:

- First get some first rate people. It must be absolutely top-notch people, maybe ten or twenty of them.

- Make sure they interact a lot.

- Allow them to do what they want – be confident that they will do something important.

- And then when you protect them and see that they are well funded, you are off and running.

Probably in seven cases out of ten that will not produce much. But quite a few times you will get something spectacular – game changing things like quantum theory or the internet.

Don’t choose programs, choose people

Q: This does not seem to be the way officials are funding science…

A: Yes, in many places you have officials telling people what they need to research. Or where people insist on performance and indices… especially in Europe, I have the impression, you have a tradition of funding science by insisting on all these things like indices and performance and publications or citation numbers. But that’s not a very good formula.

Excellence is not measurable by performance indicators. In fact that’s the opposite of doing science.

I notice at places where everybody emphasize all this they are not on the forefront. Maybe it works for standard science; and to get out the really bad science. But it doesn’t work if you want to push boundaries.

Many officials don’t understand that.

In Singapore the authorities once asked me: How did you decide on the research projects in Santa Fe? I said, I didn’t decide on the research projects. They repeated their question. I said again, I did not decide on the research projects. I only decided on people. I got absolutely first rate people, we discussed vaguely the direction we wanted things to be in, and they decided on their research projects.

That answer did not compute with them. They are the civil service, they are extraordinarily bright, they’ve got a lot of money. So they think they should decide what needs to be researched.

I should have told them – I regret I didn’t: This is fine if you want to find solutions for certain things, like getting the traffic running or fixing the health care system. Surely with taxpayer’s money you have to figure such things out. But you will never get great science with that. All you get is mediocrity.

Of course now they asked, how do we decide which people should be funded? And I said: “You don’t! Just allow top people to bring in top people. Give them funding and the task of being daring.”

Any other way of managing top science doesn’t seem to work.

I think the Hub could be such a place – all the ingredients are here. Just make sure to attract some more absolutely first rate people. If they are well funded the Hub will put itself on the map very quickly.

This interview was originally published on https://www.csh.ac.at/brian-arthurs-magic-formula-for-excellence/

Sep 25, 2017 | Water, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

Mexico City has been experiencing a major water crisis in the last few decades and it is only getting worse. To keep the water flowing, the city imports large amounts of water from as far as 150 kilometers.

Not only is this energy-intensive and expensive, it creates conflict with the indigenous communities in the donor basins. Over the last decade, a growing number of these communities have been protesting to reclaim their rights to water resources.

The ancient city of Tenochtitlan as depicted in a mural by Diego Rivera

(cc) Wikimedia Commons

As part of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program at IIASA, Francine van den Brandeler studied the struggle that Mexico City is facing as it tries to provide water to its growing population and expanding economy. Local aquifers have been over-exploited, so water needs to be imported from distant sources, with high economic, social, and environmental impacts. Van den Brandeler’s study assesses the effectiveness of water use rights in promoting sustainable water use and reducing groundwater exploitation in the city.

“A few centuries back, Tenochtitlan, the place where Mexico City stands today, was known as the lake city,” says Van den Brandeler. The Aztecs had developed a sophisticated system of dikes and canals to manage water and mitigate floods. However, that changed quickly with the arrival of the Spaniards, who transformed the natural hydrology of the valley. As the population continued to grow over the next centuries, providing drinking water became an increasing challenge, along with controlling floods. As the lake dried up, people pumped water from the ground and built increasingly large infrastructure to bring water from other areas.

Communities from lower-income groups, living in informal settlements on the outskirts of the metropolitan region are more vulnerable to this scarcity. Many live on just few liters of water every day, and do not have access to the main water supply network, instead relying on water trucks which charge several times the price of water from the public utility.

“In wealthier areas people consume much more than the average European does every day. It is a question of power and politics,” says van den Brandeler. “The voices of marginalized communities go unheard.”

Many people rely on delivery service for drinking water.

© Angela Ostafichuk | Shutterstock

The more one learns about the situation, the more complicated it becomes. The import of water started in the 1940’s. But with a massive increase in population in the last couple of decades, the deficits have become much worse.

The government’s approach has been to find more water rather than rehabilitating or reusing local surface and groundwater sources, or increasing water use efficiency, says van den Brandeler. Therefore wells are being drilled deeper and deeper—as much as 2000 meters into the ground—as the water runs out.

Some people have started initiatives to harvest rainwater, but it is not considered a viable solution by those in charge. “A lot of it has to do with their worldview and general paradigm. The people working at the National Water Commission and the Water Utility of Mexico City have been trained as engineers to make large dams and put pipes in the ground. They don’t believe in small-scale solutions. In their opinion when millions of people are concerned, such solutions cannot work,” says van den Brandeler.

Although the city gets plenty of rain during the rainy season, it goes directly into the drainage system which is linked to the sewage system. This contaminates the water, making it unusable. At the same time, almost 40% of the water in Mexico City’s piped networks is lost due to leakages.

Policy procedures and institutional functioning also remain top-down and opaque, van den Brandeler has found. One of the policy tools for curbing excess water use are water permits for bulk use, for agriculture, industry, or public utilities supplying water. Introduced in the 1940s, lack of proper enforcement has created misuse and conflicts.

For example, while farmers also require a permit that specifies the volume of water they may use each year, they do not pay for their water usage. However, it is difficult to monitor if farmers are extracting water according to the conditions in the permit. Since they do not pay a usage fee, there is also less incentive for the National Water Commission to monitor them. As a result, a huge black market has cropped up in the city where property owners and commercial developers pay exorbitant prices to buy water permits from those who have a license. Since the government allows the exchange of permits between two willing parties, they make it appear above-board. However, it has contributed to the inequalities in water distribution in the city.

With the water crisis worsening every year, Mexico City needs to find a solution before it runs out of water completely. Van den Brandeler is hopeful for a better future as she studies the contributing factors to the problem. She hopes that the water use permits are better enforced and users are given stronger incentives to respect their allocated water quotas. Further, if greater efforts are made within the metropolis to repair decaying infrastructure and scale up alternatives such as rainwater harvesting and wastewater reuse, the city won’t have to look at expensive solutions if adopted in a decentralized manner.

About the Researcher

Francine van den Brandeler is a third year PhD student at the University of Amsterdam in Netherlands. Her research is on the spatial mismatches between integrated river basin management and metropolitan water governance – the incompatibility of institutions and biophysical systems-, which can lead to fragmented water policy outcomes. Fragmented decision-making cannot adequately address the issues of sustainability and social inclusion faced by megacities in the Global South. She aims to assess the effectiveness of policy instruments to overcome this mismatch and suggest recommendations for policy (re)design. At IIASA she was part of the Water Program and worked under the supervision of Sylvia Tramberend and Water Program Director Simon Langan.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.