Jun 22, 2020 | Alumni

by Ralph L. Keeney, IIASA alumnus and Professor Emeritus at Duke University

Ralph L. Keeney is a professor and consultant about decision-making. He was a research scholar at IIASA from 1974-76, where he and Howard Raiffa finished their book Decisions with Multiple Objectives. Here he describes his most recent book, Give Yourself a Nudge: Helping Smart People Make Smarter Personal and Business Decisions, and how it can impact you.

© VectorMine | Dreamstime

Few individuals understand the key role of decisions in one’s life. That is because many things other than decisions can increase the quality of your life. If you improve your professional skills, including your decision-making skills, you will get more job opportunities and end up doing more interesting work with better pay. If you regularly exercise and eat a better diet, your fitness and health will improve. Of course this is true, but none of this could happen without initially making decisions to improve professional skills, to exercise regularly, or to eat a better diet, and then making the routine decisions to follow through to turn your plans into reality. That’s why making decisions is the tool for improving your life. The rest of your life just happens beyond your control.

We all learned to make decisions by trial and error as very few individuals have had any education or training about how to make good decisions. Hence, we each have our own decision-making style composed of habits. Over the last four decades, researchers and scientists in the fields of behavioral economics and psychology have identified numerous biases and shortcomings of the habits used by all decision-makers. A concise summary of these findings is that decisions are often not adequately understood when a choice is made, and the choice of an alternative strongly depends on how the alternatives are presented rather than on their potential impacts.

© Ralph Keeney

My new book, Give Yourself a Nudge presents numerous ways for you to limit the influence of the biases and shortcomings of your natural decision-making habits. It describes and illustrates several different types of personal nudges that guide you to make smarter decisions. These nudges help you clearly define the decision that you face, thoroughly articulate what you want to achieve by making that decision, create better alternatives to consider, and deliberately identify more desirable decisions to face. Personal nudges are applicable to all of your decisions.

My favorite personal nudge concept is called a decision opportunity. To understand this important concept, ask yourself “Who should be making your decisions?” Obviously, you should. So who should be making the decisions about which decisions you should face? This is a more challenging question. My response is that you should be making more of them than you currently are.

You do not choose the decision problems that occur due to the actions of others and circumstances beyond your control, and you must reactively address these decisions. However, you can proactively identify any specific decision that you want to face. I refer to these decisions as decision opportunities.

Pursuing a decision opportunity usually improves your life, whereas solving a decision problem rarely can improve your life. Let me explain. Most decision problems result from something that becomes worse in your life: you become sick, your car is damaged, or you lose your job. Solving such a decision attempts to restore your quality of life to its level before the decision problem occurred. When you create a decision opportunity, nothing in your life becomes worse. Pursuing a decision opportunity should improve circumstances which raises your quality of life.

To create a decision opportunity, all that you initially need to do is think about something you would really like to have or experience for yourself or others. You then define the decision opportunity as ’decide how to make that desired future a reality’. There are no limits to thoughts, so anything you envision can be the basis for a decision opportunity. After you define a decision opportunity, then address it in the same way that you do for a decision problem. Specifically, clarify all of your objectives for that decision opportunity, next create a set of potential alternatives to achieve them, and then select the alternative that best achieves your objectives.

The only reason to make any decision is to achieve something. That something is made clear by identifying the objectives for the decision, which should then guide all effort on that decision. Fully identifying all the objectives for an important policy decision is difficult and often not done. At IIASA, I developed techniques to help stakeholders articulate their objectives, which stimulates the creation of a richer set of alternatives and provides a basis for a more impactful analysis of those alternatives. Fully identifying all of the objectives for any IIASA project today is just as critical as it was in the past.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jun 15, 2020 | COVID19, Data and Methods, Demography

By Tadeusz Bara-Slupski, Artificial Intelligence for Good initiative leader, Appsilon Data Science

Tadeusz Bara-Slupski discusses the Artificial Intelligence for Good initiative’s recent collaboration with IIASA to develop an interactive COVID-19 data visualization tool.

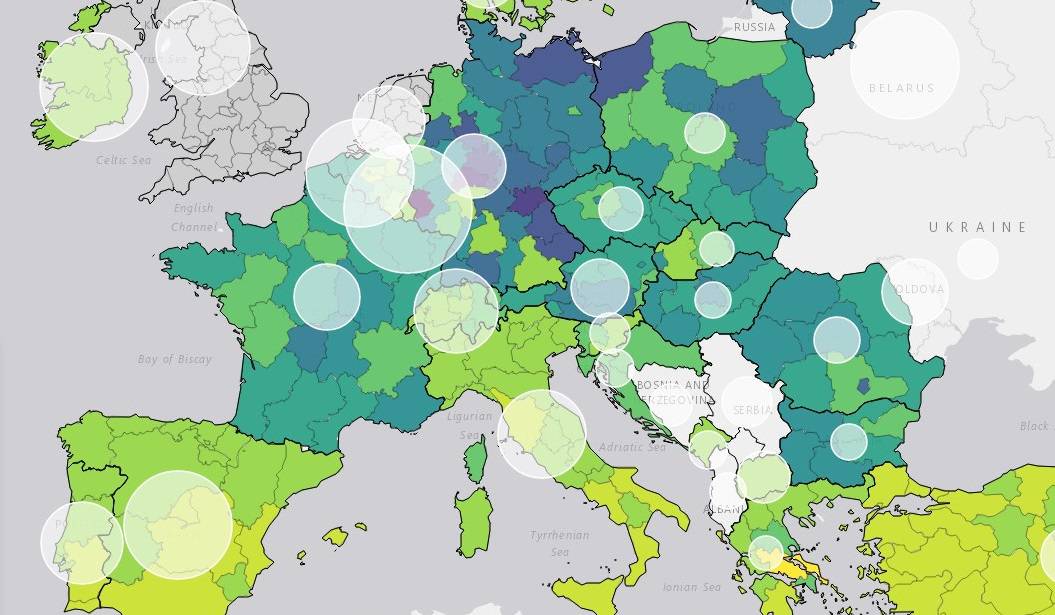

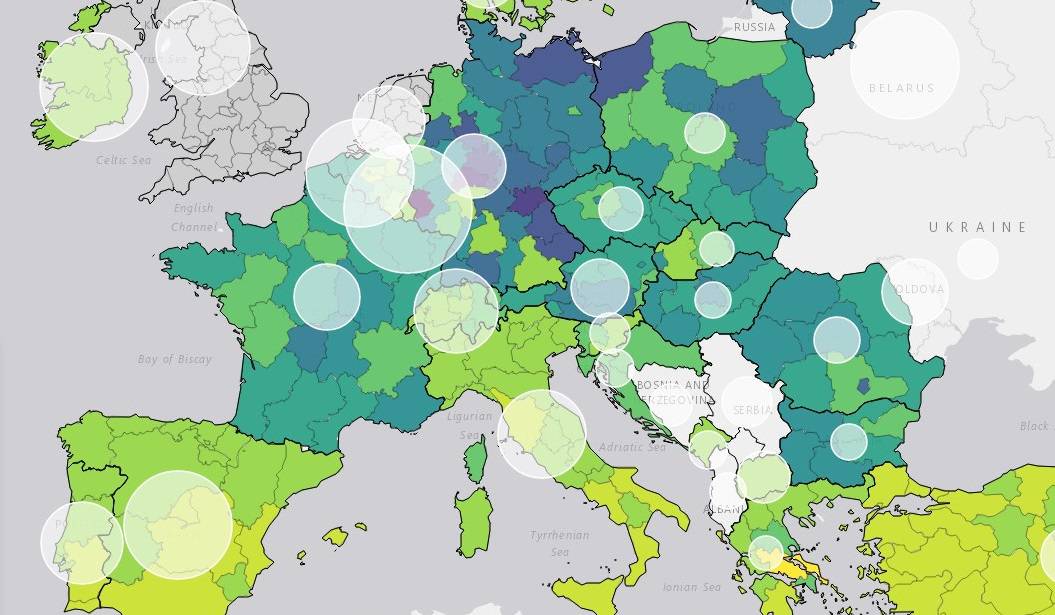

Number of hospital beds per 1000 population © IIASA

Public institutions rely on external data sources and analysis to guide policymaking and intervention. Through our AI for Good initiative, we support organizations that provide such inputs with our technical expertise. We were recently approached by IIASA to create a dashboard to visualize COVID-19 data. This builds on our previous collaboration, which had us deliver a decision-making tool for natural disaster risk planning in Madagascar. In this article, we provide an example of how to help policymakers navigate the ocean of available data with dashboards that turn these data into actionable information.

Data is useful information when it creates value…or saves lives

The current pandemic emergency has put an unprecedented strain on both public health services and policymaking bodies around the world. Government action has been constrained in many cases by limited access to equipment and personnel. Adequate policymaking can help to coordinate the emergency relief effort effectively, make better use of scarce resources, and prevent such shortages in the future. This, however, requires access to secure, timely, and accurate information.

Governments commission various public bodies and research institutes to provide such data both for planning and coordinating the response. For instance, in the UK, the government commissioned the National Health Service (NHS) to build a data platform to consolidate a number of data providers into one single source. However, for the data to be useful it must be presented in a way that is consistent with the demands of an emergency situation. Therefore, the NHS partnered with a number of tech companies to visualize the data in dashboards and to provide deeper insights. Raw data, regardless of its quality, is not useful information until it is understood in a way that creates value – or in this case informs action that could save lives.

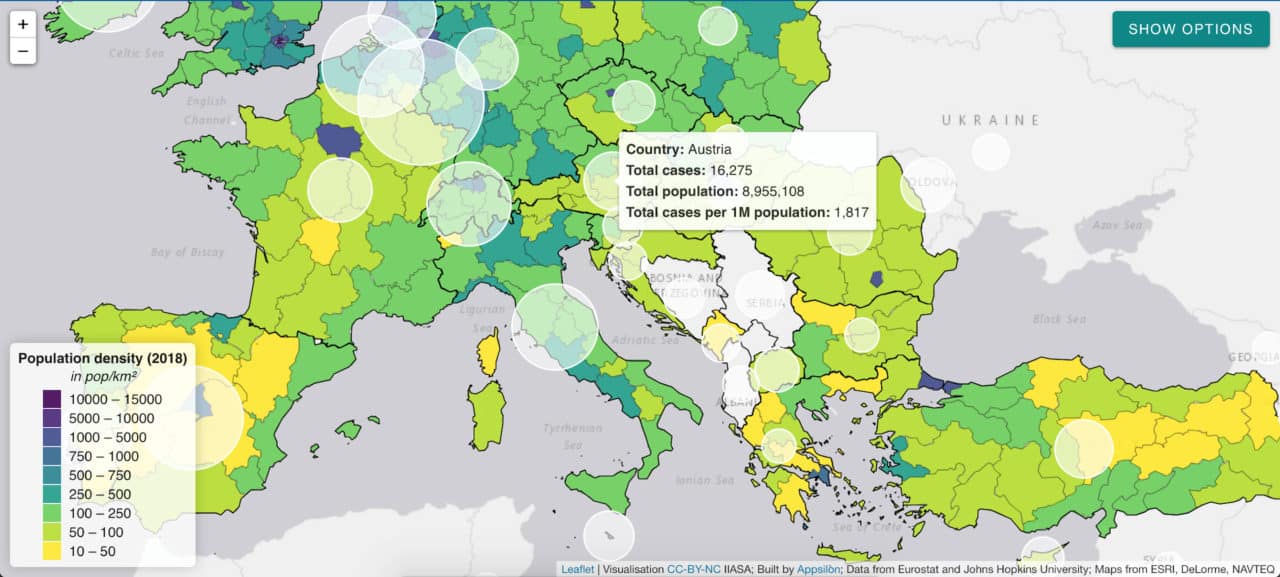

IIASA approached us to support them in making their COVID-19 data and indicators more useful to policymakers. The institute’s research is used by policymakers around the world to make critical decisions. We appreciated the opportunity to use our skills to support their efforts by creating an interactive data visualization tool.

IIASA COVID-19 report and mapbook

Research indicates that while all segments of the population are vulnerable to the virus, not all countries are equally vulnerable at the same time. Therefore, there is a need for accurate socioeconomic and demographic data to inform the allocation of scarce resources between countries and even within countries.

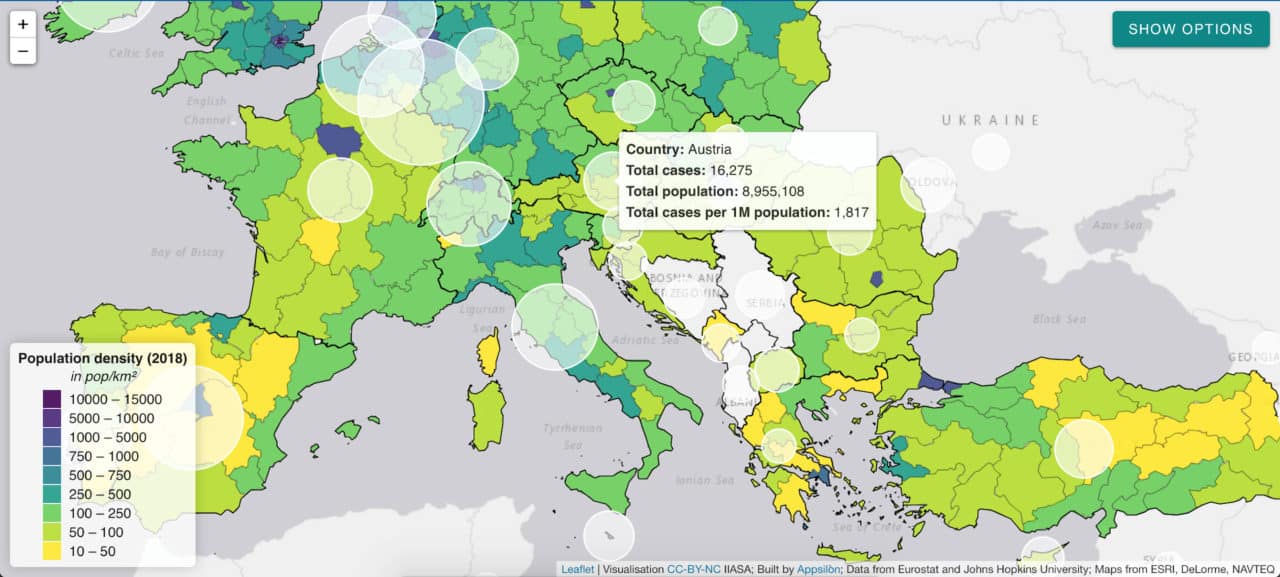

IIASA responded to this need with a regularly updated website and data report: “COVID-19: Visualizing regional socioeconomic indicators for Europe”. The reader is introduced to a range of demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related indicators for European Union member countries and sub-regions in five categories:

- Current COVID-19 trends – information about the number of cases and effectiveness of policy response measures

- Demographic indicators – age, population density, migration

- Economic indicators – GDP, income, share of workers who work from home

- Health-related indicators – information about healthcare system capacity

- Tourism – number of visitors, including foreign

The indicators and data were chosen for their value in assisting epidemiological analysis and balanced policy formulation. Policymakers often face the challenge of prioritizing pandemic mitigation efforts over long-term impacts like unemployment, production losses, and supply-chain disruptions. IIASA’s series of maps and graphs facilitates understanding of these impacts while maintaining the focus on containing the spread of the virus.

Our collaboration – a dashboard for policymakers

Having taken the first step to disseminate the data as information in the form of a mapbook, Asjad Naqvi decided to make these data even more accessible by turning the maps into an interactive and visually appealing tool.

IIASA has previously approached Appsilon Data Science with a data visualization project, which had us improve the features and design of Visualize, a decision support tool for policymakers in natural disaster risk management. Building on this experience, we set out to assist Naqvi with creating a dashboard to deliver the data to end-users even faster.

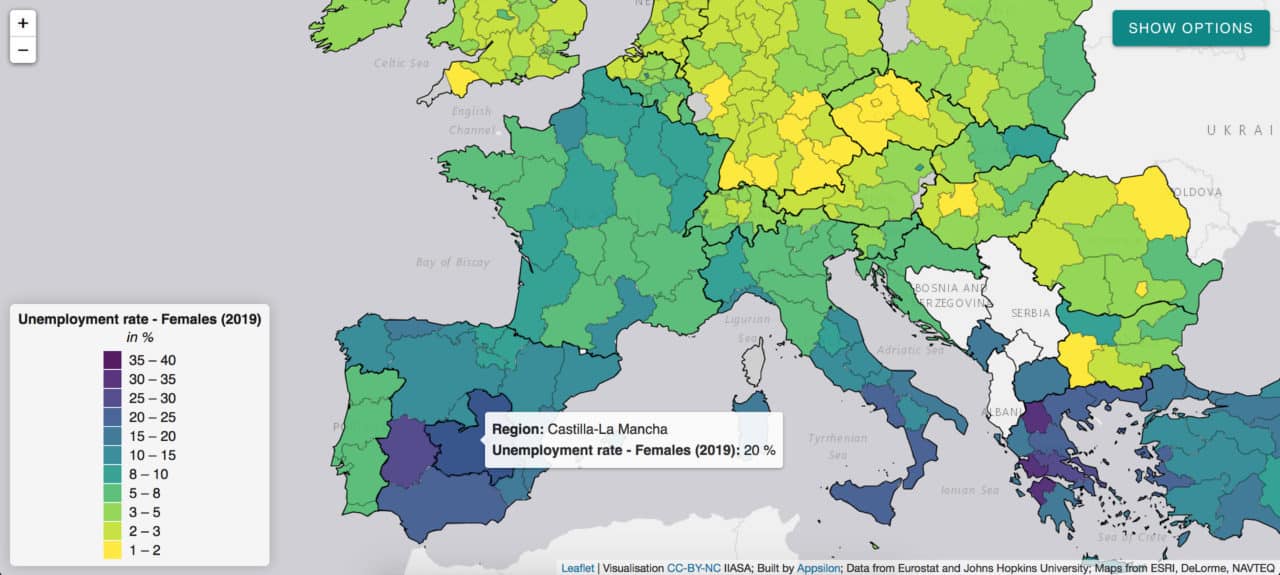

The application allows for browsing through a list of 32 indicators and visualizing them on an interactive map. The list is not final with indicators being regularly reviewed, added, and retired on a weekly basis.

White circles indicate the number of cases per 1 million citizens.

The application will continue to provide the latest and most relevant information to track regional performance in Europe also in the post-pandemic phase:

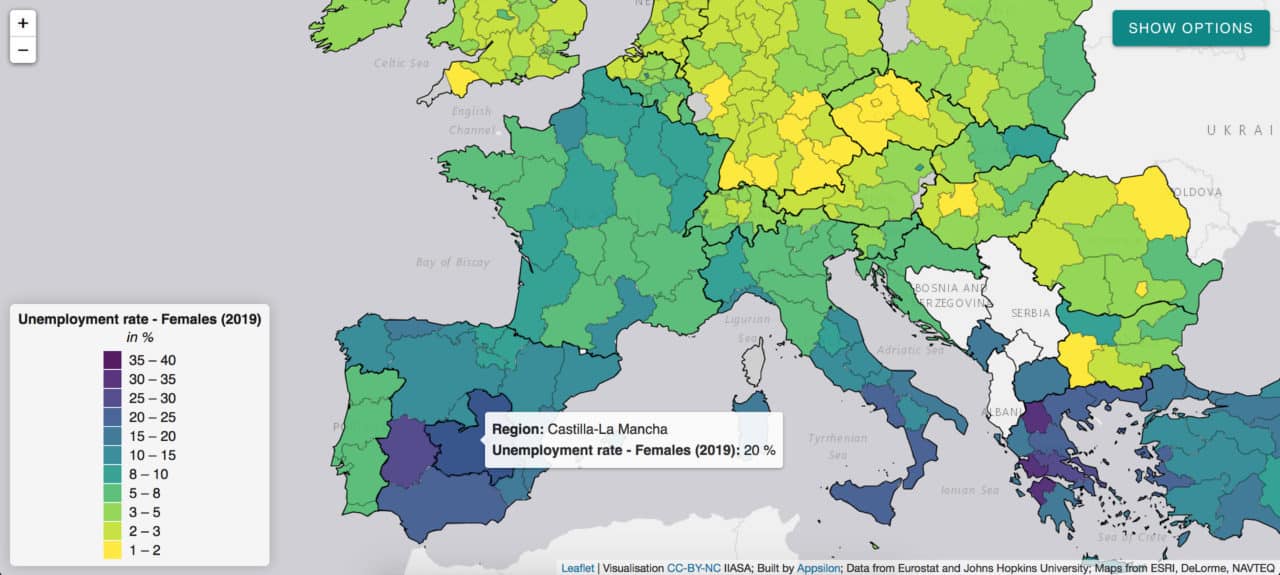

The pandemic has a disproportionate impact on women’s employment and revealed some of the systemic inequalities.

Social distancing measures, for instance, have a large impact on sectors with high female employment rates. The closure of schools and daycare facilities particularly affects working mothers. Indicators such as female unemployment rate can inform appropriate remedial action in the post-COVID world and highlight regions of special concern like Castilla-La-Mancha in Spain.

Given the urgency of the pandemic emergency, we managed to develop and deploy this application within five days. We believe such partnerships between data science consultancies and research institutes can transform the way policymakers utilize data. We are looking forward to future collaborations with IIASA and other partners to help transform data into accessible and useful information.

This project was conducted as part of our Artificial Intelligence for Good initiative. The application is available to explore here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Apr 17, 2020 | Alumni, Germany, IIASA Network, Systems Analysis

By Liza Soutschek, doctoral researcher at the Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History, Germany

Liza Soutschek shares her journey in researching the institute’s history relating to the Cold War for her PhD dissertation.

© Liza Soutschek

IIASA, Schloss Laxenburg, November 1975

Howard Raiffa, the founding director of IIASA, was about to leave Schloss Laxenburg in November 1975 to return to the USA. In his farewell address, he reflected on the institute’s first three years as an East-West research institute during the Cold War and concluded:

“My most exhilarating moments at IIASA, the times when I feel most rewarded by all our efforts, occur whenever I am present at a scientific meeting and scientists from different disciplines and cultural backgrounds argue with each other, on substantive issues, without being conscious of their roles as mathematicians or economists or management scientists or of their national identities. I will never forget those times, when [Wolf] Haefele of F.R.G. [West Germany] and [Hans] Knop of G.D.R. [East Germany] would argue heatedly on a scientific point – sometimes on the same side and at other times on opposite sides.”

As Howard Raiffa pointed out, IIASA, founded in 1972 in the wake of Cold War détente, provided an exceptional platform for scientific dialogue and exchange across borders – in particular for East and West Germans.

Intrigued by IIASA’s history

Looking back from the present day, knowing how difficult interdisciplinary collaboration between scientists from different nations and cultures can be, one question that comes up right away is: what was it like working at IIASA in the 1970s and 1980s in the context of the Cold War?

I asked myself this question when I first came across IIASA in the fall of 2017, and the spring of 2018, when I started working on a dissertation project on the institute’s East and West German history. It is done as part of a research group that examined “Cooperation and Competition in the Sciences” in case studies from a historical perspective. In my dissertation, I analyzed the relations between scientific and political actors from East and West Germany in the context of IIASA, with a focus on mechanisms of collaboration and competition at the local site as well as on wider effects in the entangled Cold War German history.

Historical research: books, dust, and coffee

Historians write books, but in order to do that we have to read hundreds of other books, look for traces in (sometimes more, sometimes less) dusty archives, and drink a lot of coffee with interesting people.

Initially my research led me to several German state and scientific archives. In the Federal Archives, for example, I found evidence of close interconnections between German science and politics during the Cold War regarding IIASA – not only in the case of the GDR, but also the FRG. Besides the intention to build a bridge between East and West, IIASA was also an arena for Cold War rivalry in the eyes of both German states. My favorite archival find were the documents of the Max Plank Society, which was the former West German National Member Organization of IIASA.

In Germany, I also had the opportunity to talk to former West German members of the IIASA energy group in the 1970s and 1980s. Among them was Rudolf Avenhaus, who started working in the energy project under the leadership of Wolf Häfele in the summer of 1973. Over several cups of coffee, he told me about his life, what it was like to work at IIASA in those years, and about his collaboration with Willi Hätscher, one of the few East Germans in the group at that time.

A visit to IIASA and an inquiry

I finally had the chance to visit IIASA in the summer of 2019. With the help of several IIASA colleagues, I explored the IIASA archive for insights into the institute’s East-West German history. I also had the opportunity to discover more by talking to former and current IIASA employees. Two conversations I want to mention in particular, were with long-term staff members Martha Wohlwendt and Ruth Steiner, who provided an alternative view of IIASA to that of the scientists. I enjoyed my visit to the beautiful Schloss Laxenburg immensely and hope to return.

After collecting all these sources, from archival records to personal interviews, I can now begin writing an account on how cooperation and competition formed the relations between East and West Germans in the context of IIASA and thus, make IIASA’s history even better known.

© Liza Soutschek

After sharing this insight into my research, I would like to end with an inquiry. If you read this and think, “I could add something to this story!”, I would be happy to hear from you. Whether you are a former German IIASA staff member or have another connection to all of this, maybe we can add another piece to the puzzle together.

Contact:

Liza Soutschek

Institut für Zeitgeschichte München – Berlin

Leonrodstr. 46b, 80636 München, Germany

soutschek@ifz-muenchen.de

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

More on the history of IIASA.

Mar 10, 2020 | COVID19, Health, IIASA Network, Wellbeing, Women in Science

Raya Muttarak, Deputy Program Director, IIASA World Population Program

Raya Muttarak writes about what we have learnt about the COVID-19 outbreak so far, and how collective mitigation measures could influence the spread of the disease.

© Konstantinos A | Dreamstime.com

Since the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China back in January, we have learnt a lot about the virus: we know how to detect the symptoms, and a vaccination is currently being developed. However, there are still many uncertainties:

We for example don’t know enough about the disease’s fatality rate – mainly because we don’t precisely know how many people are infected, which is the denominator. We also don’t know exactly how the virus spreads. Generally, it is assumed that the virus spreads from person-to-person through close contact (within about 1 meter) and through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes. It is also thought that COVID-19 can spread from contact with contaminated surfaces or objects.

In addition, knowledge about the timing of infectiousness is still uncertain. There is evidence that the transmission can happen before the onset of symptoms, although it is commonly thought that people are most contagious when they are most symptomatic. This information is crucial, because if we know the timing patterns of the transmission, we could adopt better measures around when to quarantine an infected person.

Lastly, we don’t yet know whether the spread of the disease will slow down once the weather gets warmer.

What is currently happening in Iran, Italy, Japan, and South Korea may be unique to these countries, but it is more than likely that most countries will eventually experience the spread of COVID-19. In this regard, epidemiologists have estimated that in the absence of mitigation measures, in the worst-case scenario, approximately 60% of the population would become infected. In February, Nancy Messonnier, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Centre for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases in the US, warned that “It’s not so much of a question of if this will happen anymore, but rather more of a question of exactly when this will happen.”

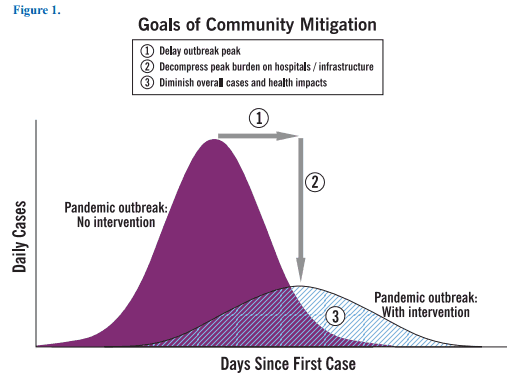

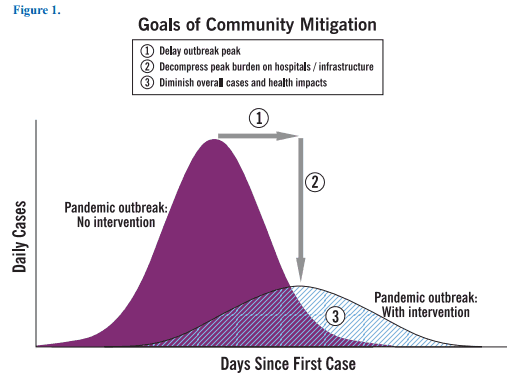

We learnt from an epidemiological transmission model that public efforts to curb the transmission of the disease should be directed towards flattening the epidemic curve. This is crucial, since the treatment of severe lung failure caused by COVID-19 requires ventilators to help patients breathe in intensive care units (ICUs). Not a single country in the world has the capacity to absorb the large number of people who would need intensive care at the same time. Experience from Italy shows that about 10% of all patients who test positive for COVID-19 require intensive care. Although efforts have been made to increase ICU capacity, the rapidly growing number of infected patients is overloading the healthcare system. Measures to reduce transmission in order to slow down the epidemic over the course of the year will therefore significantly mitigate the impact of COVID-19.

A transmission model with and without intervention.

Source: CDC. (2007). Interim Pre-pandemic Planning Guidance: Community Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Mitigation in the United States—. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The figure above shows the distribution of infectious cases with and without intervention. If the outbreak peak can be delayed, this allows the health system and healthcare professionals to bring the number of persons that require hospitalization and intensive care in line with the nation’s capacity to provide medical care. To flatten the epidemic curve and lower peak morbidity and mortality, calls for both government response and individual actions.

We will have to follow the protocol of the Austrian Health Ministry, but certain practices such as social distancing, washing hands, and avoiding gathering in crowded places, can help reduce the transmission of the disease. While it is true that young and healthy people are less likely to get sick and die from COVID-19, they can still be a virus carrier and thus transmit the disease to other vulnerable subgroups of the population, such as older people and those with underlying health conditions. An article recently published in The Lancet provides helpful information to better understand the current situation and explains why fighting against COVID-19 will take collective action.

Reference:

Anderson R, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, & Hollingsworth T (2020). How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet 0(0) DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 10, 2019 | Alumni, IIASA Network, Women in Science

By Luiza Toledo, Science Communication Fellow 2019

Luiza Toledo writes about how the IIASA Women in Science Club are creating a safe space to talk about and advance gender equality in science.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 is to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. A recent report titled, Harnessing the power of data for gender equality produced by Equal Measures 2030, however, shows that we still have a long way to go before this goal becomes a reality.

Countries in Europe and North America, along with two in the Asia-Pacific region (Australia and New Zealand), achieved the highest scores in terms of gender equality on the 2019 SDG Gender Index. However, even in the 20 top scoring countries, there are still indicators that score low. This suggests that even the countries with high overall scores for gender equality are struggling with thorny issues – one of them being women in science and technology research positions.

As an international institute, IIASA was founded on the principles of equal opportunity, which naturally includes equality in terms of gender balance. The institute’s 2018 Annual Report shows that the number of early-career female IIASA scientists has steadily been growing over the last few years. Since 2016, the number of female researchers increased by 24%, with most of the new hires joining as research assistants. Despite this increasing trend, the gap for PhD level researchers is as high as it has ever been with men outnumbering women four to one. In addition, there is a lack of female scientists in the over-40 age group, which is by no means unique to IIASA. Researchers who study gender and science have even compared women’s careers in science with a leaky pipeline – a flawed channel system that loses quantity before it reaches the destination.

©Liebentritt_Christoph

Even though it is unrealistic to expect a 100% retention of women in science related careers (or any career for that matter), male researchers still have a much higher retention rate in scientific careers than their female colleagues do, and this is where the problem lies. According to the IIASA Diversity and Work Environment Report from 2015, male researchers at IIASA on average stay with the institute for seven years, whereas female researchers stay for only four years. To overcome the leaky pipeline effect, we should start creating a workplace culture that aims to recruit and retain women and is more open to discussing and tackling gender issues in academia, thereby developing a safe networking space.

The Women in Science Club (WISC) at IIASA is a great example of a safe networking space that embraces gender equality and shows the power of women that support other women. Co-led led by Amanda Palazzo, a researcher in the institute’s Ecosystems Services and Management Program, and IIASA Network and Alumni Officer Monika Bauer, the club has a self-proclaimed mission to build a network where women connected to science can share experiences, empower themselves, and highlight the work of other women connected to science.

The idea of creating a network of women in science came about in the fall of 2016 when former Finnish President, Tarja Halonen, visited IIASA. During her visit, she asked to meet with the women of IIASA to talk about diversity and equity issues. This conversation was the first of several meetings that are now attended by women (and men) across the institute under the auspices of WISC.

“The conversation was inspiring and after that first meeting, a few of us thought about organizing a club to continue working on the issues that came up from our discussion with President Halonen,” explains Palazzo.

Nowadays, the WISC organizers arrange lunchtime meetings known as “Meet, greet, and eat” sessions to coincide with visits to IIASA by prominent researchers and other professionals from IIASA and elsewhere who want to share their experiences.

“I’ve found that more experienced and senior women who may have been the only women in their departments at the start of their careers or may have had to fight for a seat at the table are often the quickest to agree to meet with WISC. This shows me that they see the value in a club like ours,” Palazzo adds.

Although the number of women now engaged in science is the highest it has ever been, there are still too few women in positions of leadership. According to Palazzo, at IIASA, this situation is set to change with the institute’s newly appointed Deputy Director General for Science who joined IIASA in November this year.

“I’m excited that Leena Srivastava has joined us and I hope that this is just the start of many changes at IIASA that will bring more women into positions of leadership,” she says.

Palazzo says that the most valuable thing that she has learned so far is that no two women have the same story or path to success.

“I found it reassuring to hear successful women tell us that when they were starting out or even several years into their careers they also didn’t know exactly what contribution they wanted to make. They were learning as they went along. It has also been useful to hear women talk about building resilience to negative comments or behaviors and recognize that these behaviors reflect the other person’s fear and insecurity. In the end, the Women in Science Club is a place to share, contribute, listen, and learn. We want women connected to science to feel that they are a member of our community, that they have a seat at our table, and that they belong here,” she concludes.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.