Jun 4, 2018 | Demography, Postdoc, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science

©Nandita Saikia

By Nandita Saikia, Postdoctoral Research Scholar at IIASA

Being an author of a research article on excess female deaths in India in Lancet Global Health, one of the world’s most prestigious and high impact factor public health journals, today I questioned myself: Did I dream of reaching here when I was a little school going girl in the early nineties in a remote village in North East India?

I am the fourth daughter of five. In a country like India, where the status of women is undoubtedly poorer than men even now, and newspapers are often filled with heinous crimes against women, you may be able to imagine what it meant being a fourth daughter. Out of five sisters, three of us were born because my parents wanted a son. My mother, who barely completed her school education, did not want more than two children irrespective of sex, but was pressurized by the extended family to go for a boy after a third daughter and six years of repeated abortions.

I was told in my childhood that I was the most unwanted child in the family. I was a daughter, terribly underweight until age 11, and had much darker skin than my elder sisters and most people from our area, who have fairer skin than average in India. At my birth, my father, a college dropout farmer, was away in a relative’s house and when he heard about the arrival of another girl, he postponed his return trip.

This is a real story, but just one of those still happening in India. The fact that the girls of India are unwanted was observed from the days of early 20th century when it was written in the 1901 census:

“There is no doubt that, as a rule, she [a girl] receives less attention than would be bestowed upon a son. She is less warmly clad, … She is probably not so well fed as a boy would be, and when ill, her parents are not likely to make the same strenuous efforts to ensure her recovery.”

Regrettably, our current study shows that negligence against “India’s daughter” continues to this day.

Discrimination against the girl child can be divided in two categories: before birth and after birth. Modern techniques now allow sex-selective abortion. Despite strong laws, more than 63 million women are estimated to be ‘missing’ in India and the discrimination occurs at all levels of society.

Our present study deals with gender discrimination after birth. We found that over 200,000 girls under the age of five died in 2005 in India as a result of negligence. We found that excess female mortality was present in more than 90% of districts, but the four largest states of North India (Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh) accounted for two thirds of India’s total number.

I have to tell you that I was luckier than most girls. Although I was an unwanted child in our extended family, to my mother, this underweight, dark-skinned, little girl was as cute as the previous ones! She gave her best care to her daughter, and she named her “Rani” meaning “Queen” in Assamese. I am still called by this name in my family and in my village.

When I grew up, I asked her several times about her motive for calling me Rani. She always replied: “You were so ugly, the thinnest one with dark skin, I named you as “Rani” because I wanted everyone to have a positive image before seeing you! Also, it is the name of my favorite teacher in high school and she was also a very thin but bright lady!”

The positive conversations with my mother played a crucial role to my desire to have my own identity, and influenced greatly my positive image of myself and my belief that I could do something worthwhile with my life. Much later, when I started my PhD at International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, I was surprised to learn that in Maharashtra, one of the wealthiest states of India, second or third daughters are not even given a name, but instead are called ‘Nakusha’, meaning unwanted.

My parents were passionate about educating their daughters, even with their limited means. My father, who was disappointed at my birth, left no stone unturned for my education! By the time I completed secondary school, our village, as well as neighboring villages, congratulated me during the Bihu celebration (the biggest local gathering) for my good performance in school exams. My parents were proud of me by that time; yet, for some strange reason, they always felt themselves weaker than our neighbors who had sons.

Now, people from our village are proud of me not just because I teach in India’s premier university, or that I take several overseas trips in a year, but because they realize that daughters can equally bring renown to their village; daughters can be married off without a dowry; daughters can equally provide old age care to their parents; daughters too can buy property! Due to this attitude and lower fertility levels, many couples now don’t prefer sons over daughters. In a village of 200 households, there are 33 couples that have either one or two daughters, yet did not keep trying for sons. In my own extended family, no one chooses to have more than two children irrespective of their sex. The situation has changed in my village, but not everywhere.

What is the solution of this deep-rooted social menace? We cannot expect a simple solution. However, my own story convinces me that education can be a game changer, but not necessarily academic degrees. I mean a system by which girls realize their own worth and their capability that they can be economically and socially empowered and can drive their own lives. With the help of education, I made myself from an “unwanted” to a wanted daughter!

The purpose of sharing my story is neither self-promotion nor to gain sympathy, rather to inspire millions of girls, who face numerous challenges in everyday life just because of their gender, and doubt their capability, just like I did in my school days. They can make a difference if they want! Nothing can stop them!

Aug 30, 2017 | Environment, Food & Water, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

Two things are distinctly noticeable when you meet Cornelius Hirsch—a cheerful smile that rarely leaves his face and the spark in his eyes as he talks about issues close to his heart. The range is quite broad though—from politics and economics to electronic music.

Cornelius Hirsch

After finishing high school, Hirsch decided to travel and explore the world. This paid off quite well. It was during his travels, encompassing Hong Kong, New Zealand, and California, that Hirsch started taking a keen interest in economic and political systems. This sparked his curiosity and helped him decide that he wanted to take up economics for higher studies. Therefore, after completing his masters in agricultural economics, Hirsch applied for a position as a research associate at the Austrian Institute of Economic Research and enrolled in the PhD-program of the Vienna University of Economics and Business to study trade, globalization, and its impact on rural areas. Currently, he is looking at subsidies and tariffs for farmers and the agricultural sector at a global scale.

As part of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program at IIASA, Hirsch is digging a little deeper to analyze how foreign direct investments (FDI) in agricultural land operate. “Since 2000, the number of foreign land acquisitions have been growing—governmental or private players buy a lot of land in different countries to produce crops. I was interested in knowing why there are so many of these hotspots in the world— sub-Saharan Africa, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia—why are people investing in these areas?,” says Hirsch.

Farming in one of the large agricultural areas in Indonesia ©CIFOR I Flickr

Increased food demand from a growing world population is leading to an increased rate of investment in agriculture in regions with large stretches of fertile land. That these regions are largely rain-fed make them even more attractive for investors as they save the cost of expensive irrigation services. In fact, Hirsch argues that “the term land-grabbing is misleading. It should actually be water-grabbing as water is the foremost deciding factor—even more important than simply land abundance.”

Some researchers have found an interesting contrast between FDI in traditional sectors, such as manufacturing, and the ones in agricultural land. While investors in the former look for stable institutions and good governmental efficiency, FDI in land deals seems to target regions with less stable institutions. This positive relationship between corruption and FDI is completely counterintuitive. Hirsch says that one reason could be that “sometimes weaker institutions are easier to get through when it comes to such vast amount of lands. A lot of times these deals and contracts are oral and have no written proof—the contracts are not transparent anyway.”

For example in South Sudan, the land and soil conditions seem to be so good that investors aren’t deterred despite conflicts due to corrupt practices or inefficient government agencies.

One of the indigenous communities in Madagascar, a place which is vulnerable to land acquisitions © IamNotUnique I Flickr

One area that often goes unnoticed is the violation of land rights of indigenous communities. If a government body decides to sell land or give out production licenses to investors for leasing the land without consulting the actual community, it is only much later that the affected community finds out that their land has been given away. Left with no land and hence no source of livelihood, these communities are forced to migrate to urban areas.

A strain of concern enters his voice as Hirsch talks about the impact. “Land as big as two times the area of Ecuador has been sold off in the past—but it accounts for a tiny percentage of the global production area.” With rising incomes and greater consumption of meat, a lot of land is used to produce animal feed crops. “This is a very inefficient way of using land,” he says.

During the summer program at IIASA, Hirsch is generating data that will help him look at these deals in detail and analyze the main factors that are taken into consideration before finalizing a land deal. At the moment he is only able to give an overview of land-grabbing at the global level. With more data on the location of the deals he can look at the factors that influence these decisions in the first place such as the proximity between the two countries involved in agricultural investments and the size of their economies.

While there is always huge media coverage when a scandal about these land acquisitions comes out in the open, Hirsch seems determined to dig deeper and uncover the dynamics involved.

About the researcher

Cornelius Hirsch is a research associate at the Austrian Institute of Economics and Research (WIFO). At IIASA he is working under the supervision of Tamas Krisztin and Linda See in the Ecosystems Services and Management Program (ESM).

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 1, 2017 | Demography, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

© KonstantinChristian I Shutterstock

Faced with a sharp decline in the global fertility levels over the last few decades, many countries today are confronted with the problem of an aging population. This could translate into an economic threat: higher health-care costs for the elderly coupled with a shrinking working population will lead to lower income-tax revenues to provide for these rising costs. This can already be seen in countries like Japan, Spain, and Germany. With an increasing number of elderly dependents and not enough workers to replace them, their social support systems have become increasingly strained.

Even though in the last few decades there has been an increase in individual incomes, researchers have observed a negative correlation between the increased wealth and the number of children people choose to have. Sara Loo, as part of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), seeks to explore why people are choosing to have fewer children as their social and economic conditions change for the better.

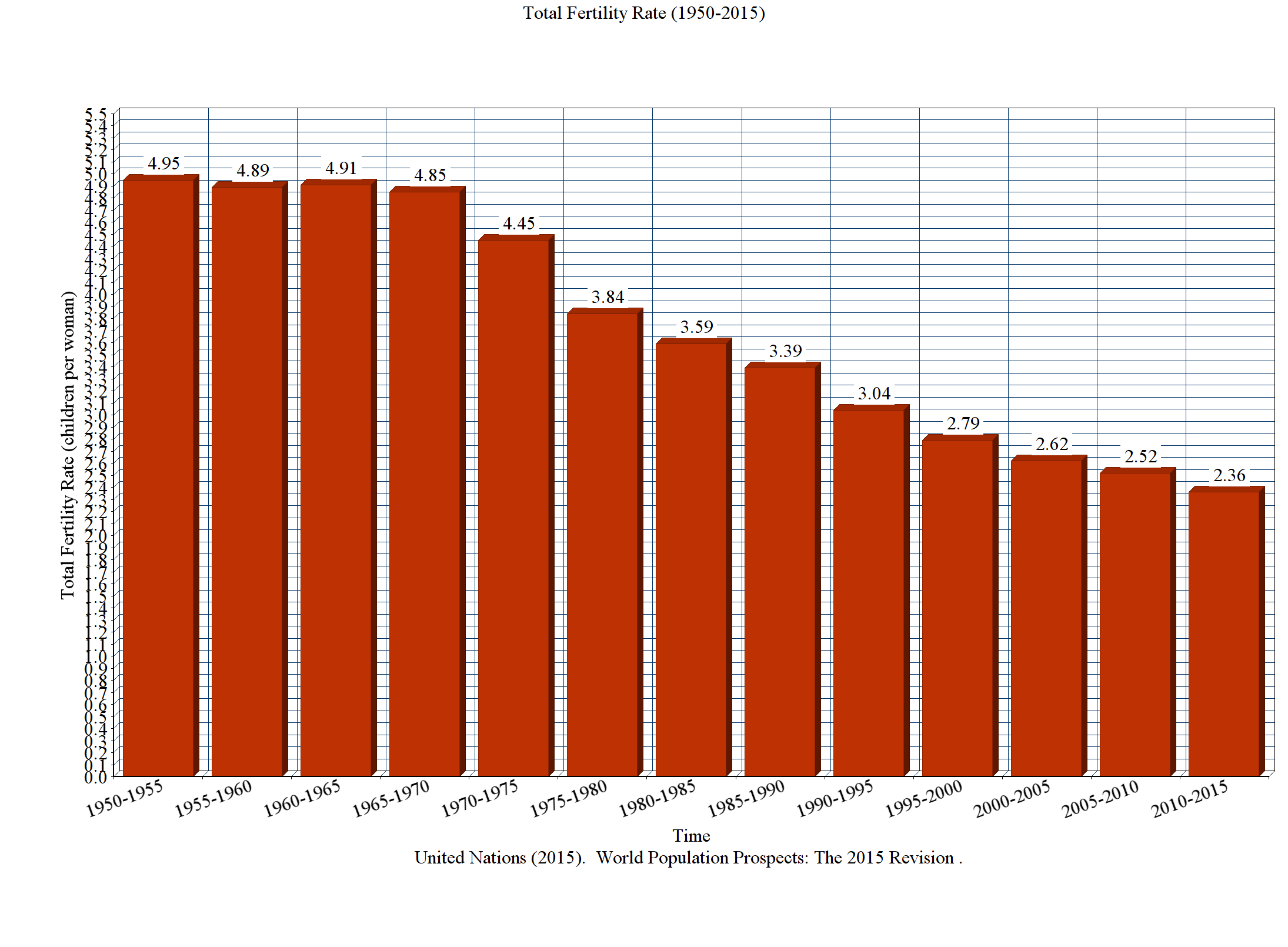

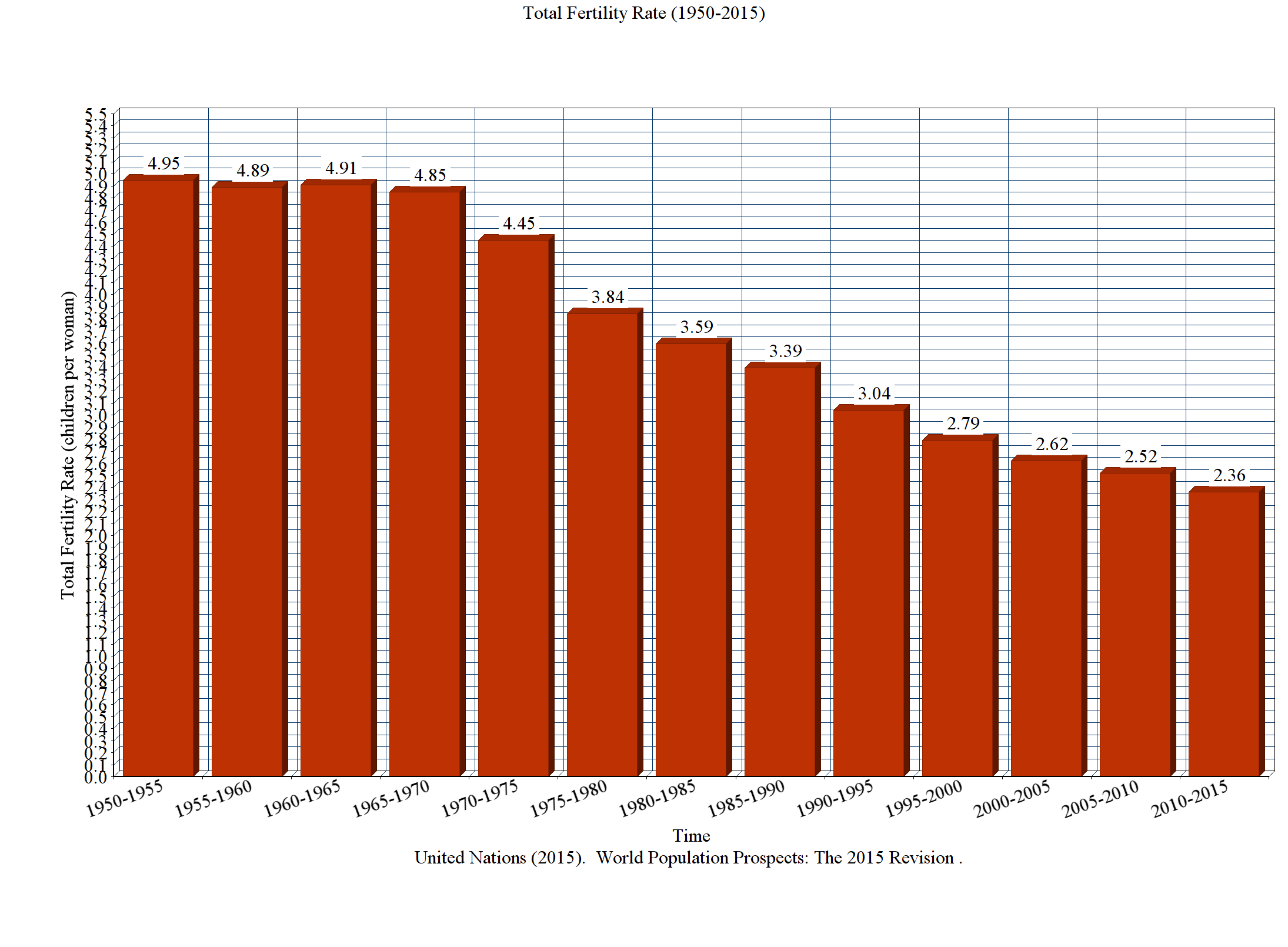

According to a report titled World Fertility Patterns 2015, global fertility levels have gone down from just above five children in 1950 to around 2.5 children per woman in 2015. In the figure below, ‘total fertility rate’ refers to the average number of children that are born to a woman over her lifetime.

It might seem counterintuitive that better living standards would be linked to decreased fertility. One way to explain it is through the lens of cultural evolution. Loo explains that culture is constantly changing – be it beliefs, knowledge, skills, or customs. This change is reflected in people’s day-to-day behaviors and affects their choices, both professional and personal. Importantly, beliefs and customs are acquired not only from people’s parents but are largely influenced by their peers – friends and colleagues.

One of the ways in which cultural evolution has affected fertility rates is resulting from the trade-off between the number of children and the quality of life that parents desire to give each of them, says Loo. As both men and women vie for well-paying jobs to attain a higher standard of living, and as they compete for such jobs based on their education, the resources parents invest into each child’s upbringing, including education and inheritance, are crucial. Even the time parents can give to their children becomes an expensive currency.

This makes for a highly competitive environment in which everyone is trying to achieve a higher status, in order to provide better opportunities for their children. When parents have fewer children, this means giving each of them a greater chance of achieving higher status.

Loo elaborates that as everyone competes to get their children to the top of the socioeconomic ladder, this necessitates a higher investment per child, both monetarily and otherwise. The theory of cultural evolution in this case thus predicts lowered fertility as competition for well-paying jobs intensifies with a country’s development.

However, it is not that such parental strategies apply equally to all segments of a population, says Evolution and Ecology Program Director Ulf Dieckmann, who is supervising Loo’s research at the institute over the summer. He explains that it is therefore helpful to look at fertility in relation to people’s socioeconomic status, instead of just looking at a population’s average fertility rate over time.

This can give telling insights. “In many pre-industrial societies, the rich had greater numbers of children, and if anybody had less than replacement-level fertility, it was the really poor people who could not afford to raise as many children. It was over time that this correlation changed from positive to negative when richer people decided to have fewer children: if they had too many children, they could not afford to invest as much per child as was needed to secure maintaining or raising the children’s socioeconomic status. This has led to a reversal of the traditional pattern: in developed societies, fertility has been shown to drop at high socioeconomic status,” says Dieckmann.

Complementing existing research on the fertility impacts of urbanization and of women’s education and liberation, Loo plans to explore how the aforementioned mechanisms of cultural evolution can explain the observed negative correlation between socioeconomic status and fertility. Her goal is to do so using a mathematical model that can account for both economic trends and cultural trends as two key processes influencing fertility rates.

About the researcher

Sara Loo is currently a third-year PhD candidate at the University of Sydney, Australia, where her research focuses on the evolution of uniquely human behaviors. Loo is working with the Evolution and Ecology Program at IIASA over the summer, with Professor Karl Sigmund and Program Director Ulf Dieckmann as her supervisors for the project.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Apr 3, 2017 | Demography

By Roman Hoffmann, Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW and WU), Vienna Institute of Demography, Austrian Academy of Sciences

Flooded street in Meycauayan, Bulacan, Philippines (credit: Kasagana-Ka Development Center Inc., 2016 )

Floods, droughts, and tropical storms have significantly increased, both in frequency and intensity in recent years. The burden of these events—both human and economic—falls in large part on low and middle-income countries with high exposure, such as coastal and island nations. In a recent study, with IIASA researcher Raya Muttarak, we found that education significantly contributes to increasing disaster resilience among poor households in the Philippines and Thailand, two countries which are frequently affected by natural calamities.

In these countries, public disaster risk reduction is important, yet public measures, such as investments in structural mitigation for large buildings or infrastructure, implementation of early warning systems, or planned evacuation routes and shelters, may not be enough to sufficiently protect communities from the devastating impacts of natural calamities. In addition, the undertaking of individual preparedness measures by households, such as stockpiling of food and water, strengthening of house structures, and having a family emergency plan, is crucial. Yet, even in areas which are heavily exposed to disasters, people often do not take any precautionary measures against environmental threats.

How people can be motivated to take precautionary action has been a fundamental question in the field of risk analysis. In the new study, which was based on face-to-face interviews in both Thailand and the Philippines, we found that prior disaster experience, which is influenced by geographical location of the home, is one of the key predictors of disaster preparedness. For those who were affected by a disaster in the recent past, education does not seem to play a significant role—they have already learned by experience. However, among those who had not previously been affected, educational attainment becomes a key determinant. Even without having experienced a disaster, the educated are more likely to make preparations. In fact, educated people who haven’t experienced a disaster have preparedness levels that are as high as those of households who were only recently affected. Since education improves abstract reasoning and abstraction skills, highly educated individuals may not need to experience a disaster to understand that they can be devastating. This suggests that education, as a channel through which individuals can learn about disaster risks and preventive strategies, may effectively serve as a substitute for (often harmful) disaster experiences as a main trigger of preparedness actions.

In additional analyses, we investigated through which channels education promotes disaster preparedness by looking at the relationship between education and different mediating factors such as income, social capital and risk perception, which are likely to influence preparedness actions. We found that how education promotes disaster preparedness is highly context-specific. In Thailand, we found that the highly educated have higher perceptions of disaster risks that can occur in a community as well as higher social capital (measured by engagement in community activities) which in turn increase disaster resilience. In the Philippines, on the other hand, it appears that none of the studied mediating factors explain the effect of education on preparedness behavior.

Emergency shelter, San Mateo, Rizal, Philippines (credit: Kasagana-Ka Development Center Inc., 2013 )

Certainly, it remains important for national governments to invest in disaster risk reduction measures such as early warning systems or evacuation centers. However, our study suggests that public funding in universal education will also benefit precautionary behavior at the personal and household level. In line with recent efforts of the UN to promote education for sustainable development, our study provides solid empirical evidence confirming the important role of education in building disaster resilience in low and middle-income countries.

Reference

Hoffmann, R. & Muttarak, R (2017). Learn from the past, prepare for the future: Impacts of education and experience on disaster preparedness in the Philippines and Thailand. World Development [doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.02.016]

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 27, 2017 | Demography

By Anne Goujon, IIASA World Population Program

Less than 6% of the working age population has a post-secondary education in sub-Saharan Africa, according to the Wittgenstein Centre Data Explorer. However, there is a huge diversity of experiences in the region: those countries located in Southern and Western Africa have higher shares of highly educated people compared to those in Eastern and Middle Africa.

The potential for increasing education levels is tremendous as there is a huge demand for higher education, partly driven by rapid population growth. The population in the age of attending higher education—18–23 years—is forecasted to increase by 50% from its 2015 level (110 million) by 2035 (183 million), and will have doubled by 2050 to 235 million. The number of colleges and universities in the region has been burgeoning to fulfill the demand. Those are not always of very good quality, whether they are in the public sector or the private, as most are. While regulatory bodies exist to check whether all education providers meet national and international standards, they are not universal.

A 2015 graduation ceremony for the Open University of Sudan. ©Hamid Abdulsalam, UNAMID via Flickr

The expansion of higher education has led to substantial brain drain to Europe, North America, and Australia, because highly educated find better opportunities there for studying and jobs–and better salaries. Researchers have estimated that in some countries such as Eritrea, Ghana, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Uganda, more than a third of the national high-skilled labor force had migrated to OECD countries in 2000. While remittances that these people send home help compensate and reinforce the education in their countries of origin, they do not compensate for the departed skills and knowledge.

These facts about education in sub-Saharan Africa are well-known to education professionals and researchers in the field. But as we show in a new book Higher Education in Africa: Challenges for Development, Mobility and Cooperation, published in January 2017, there are a lot of other aspects of education in the region that are not so well-known and that could provide interesting avenues for further research.

For instance, you probably did not know that the African Union has a higher education harmonization strategy. The general idea is the same as the Bologna process in Europe: enhance the mobility of students by making higher education systems more compatible and by strengthening the quality assurance mechanisms. One chapter by Emnet Tadesse Woldegiorgis, which looks at the process of harmonization of higher education in Sub-Saharan Africa, shows that it follows in the footsteps of the Bologna process mostly because of the involvement of international donors and of the strong links between African universities and European ones.

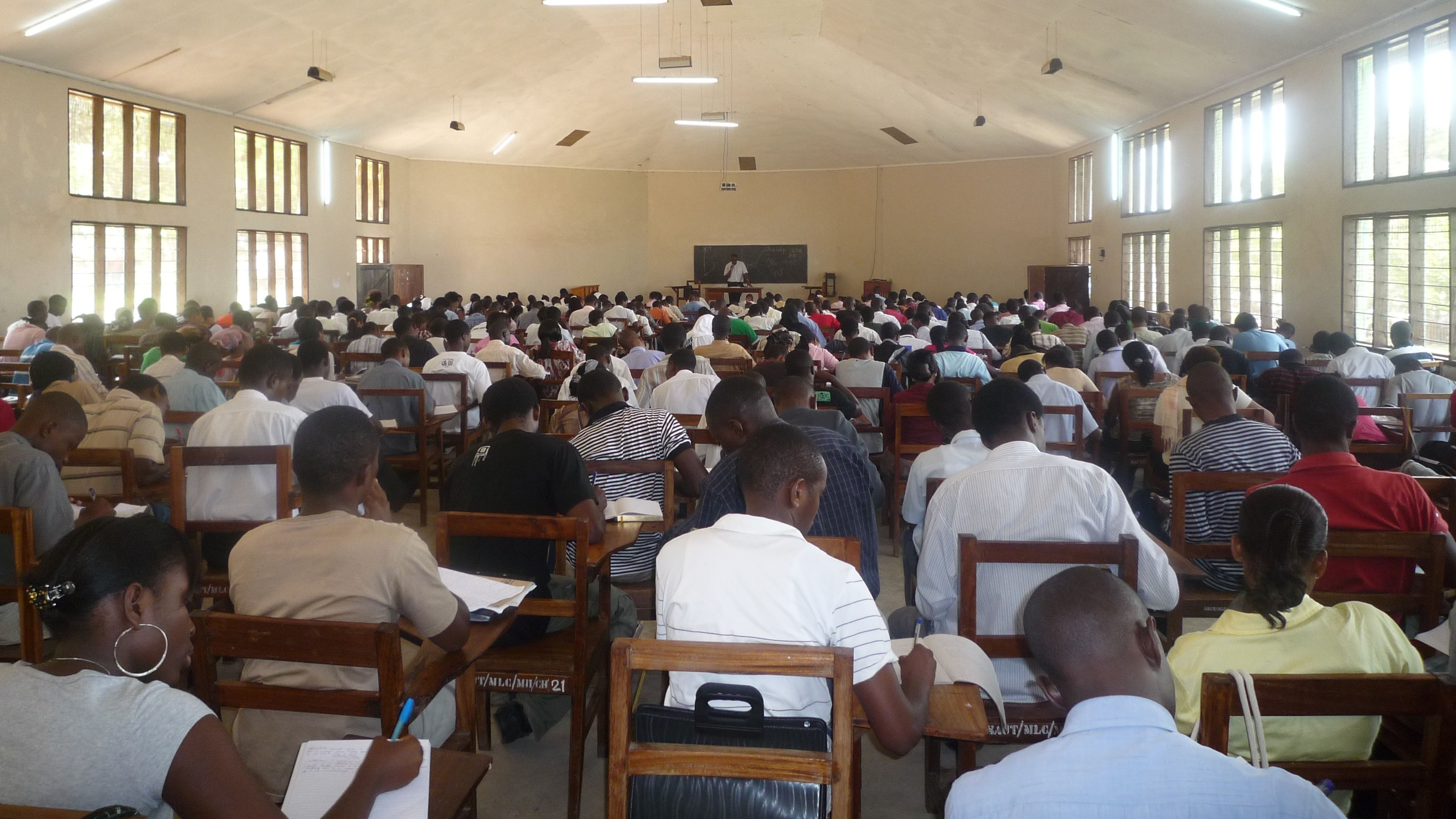

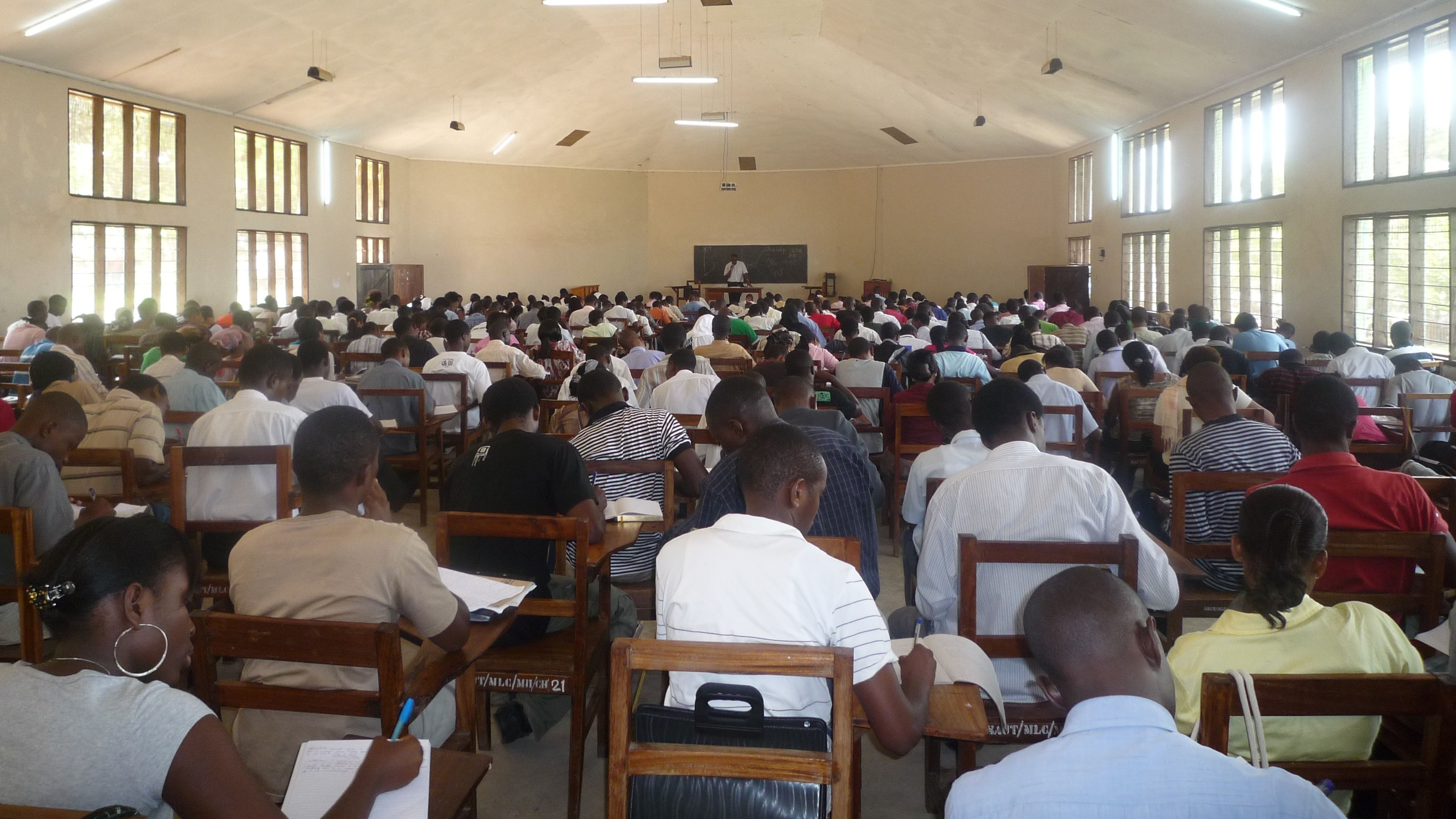

Students in lecture room at St. Augustine University of Tanzania © Max Haller and Bernadette Mueller Kmet 2009

Many chapters of the book look at the mobility of more highly educated people between Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. This is the case of a chapter by Julia Boger who interviewed graduates from Germany returning to their countries of origin: Ghana and Cameroon. The experiences of those graduates from the two West African countries are radically different: because mainly of their networks, the Ghanaian graduates face less difficulties in finding a job upon return to their country than the Cameroonians.

The last part of the book looks at some cooperation programs that are in place between the North and South (also between the South and the South). Lorenz Probst and colleagues, in their chapter, report about the challenges in implementing a transdisciplinary course in Africa within the context of the rather compartmentalized sectors of higher education in Africa.

The development of higher education could push forward change and innovation, just as much as capacity building in sub-Saharan Africa where it is direly needed.

Reference

Reference

Goujon, Anne, Max Haller, and Bernadette Müller Kmet. 2017. Higher Education in Africa: Challenges for Development, Mobility and Cooperation. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.