Jun 5, 2020 | COVID19, Demography, Health, IIASA Network

By Tomas Sobotka, Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (Univ. Vienna, IIASA, VID/ÖAW), Vienna Institute of Demography

Does COVID-19 affect men and women differently? Tomas Sobotka sheds light on the demographics of the coronavirus pandemic in Europe.

© Florin Seitan | Dreamstime.com

A question from a Time magazine article has a clear underlying message: “Why is COVID-19 striking men harder than women?” By now, everyone has learned that men are more vulnerable to COVID-19 and, if infected, they tend to die much more often than women.

Are men however also more likely to get infected? On the face of it, the number of infections by gender suggests an almost perfect gender equality. Women represent on average 47% of all infections in 70 countries reporting the number of cases by sex, as listed in the online data tracker by Global Health 5050.

Case settled? Not quite yet. The aggregated total number might be deceiving. To understand an underlying story, one has to dig into the age and sex components of total infections. The overall balance of COVID cases by gender is an outcome of age- and sex-specific patterns of infection rates and the actual age- and sex composition of the population. This in turn, is often gender-unequal, especially at older ages, due to excess mortality among men and higher longevity of women.

In fact, in ten European countries I examined with colleagues from the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital, including Raya Muttarak from the IIASA World Population Program, it turns out that infection rates are highly gendered, especially when looking at the age pattern of coronavirus infection. From the teenage years up until their late 50s, women are more likely than men to be infected with COVID-19. Women in their 20s display the biggest gender gap in infections: on average only 64 men were infected per 100 infected women aged 20-29. After age 60, the pattern reverses, as infection rates among women drop at age 60-69 and the male infection rates go up or stay stable. This crossover is also clearly visible in the charts for Belgium, Czechia, Germany, and Italy. Between ages 60 and 79, men are more likely than women to be infected. The imbalance is sharpest among people in their 70s, with an average of 136 infected males per 100 infected women. This puts older males at a double disadvantage: they are more likely to be infected and, once infected, they are much more likely to die (with both higher age and being a male identified as important risk factors).

Is our evidence credible? Clearly, many infections are undetected and our data are affected by different testing availability and testing priorities across countries. It is possible that women of working age get more frequently tested than men as women tend to be more concerned about their health. This would bias the estimated share of infected women upwards. However, the remarkable regularity in the age- and gender-pattern of infections in the analyzed countries suggests that the observed gender disparities are real. The same gender disparity by age is observed in Czechia, Denmark, Germany, and Norway with relatively few infections, as well as in Belgium, England, Italy, and Spain with high numbers of reported infections. Of course, countries differ in their gender imbalance, especially at younger ages: the gender gap is, well, gaping, in Belgium, which reports only 34 infected men per 100 infected women at age 20-29. It is much smaller in Czechia, Germany, and Norway, but the female dominance at young ages and the male dominance at older ages, with a crossover around age 60, is consistently found in each society we studied.

What’s the likely explanation? At younger ages, the smoking gun points at women’s employment and occupations. Most women of working age in Europe are employed. This may also partly explain why European countries actually register a higher number of infections among women than most other countries, with an average share of 55%. More importantly, women are often working in professions that are most exposed to the infection. Think of nurses, medical doctors, other healthcare professionals, but also all the care workers in retirement homes, which turned out in some countries to be the focal points of infection. The switch in gender balance occurs right around the retirement age. The higher likelihood of infection among older men is probably linked with their poorer health and lower immunity.

If employment is potentially risky for women, staying at home with children—itself a product of ingrained gender inequalities in work and care—may lead to fewer infections. In countries where women’s employment dips after age 30 due to their extensive parental leaves, infection rates often show a distinct dip after that age as well, going up again in their 40s: Czechia, Germany, and partly Norway and Switzerland show such an M-shaped pattern of infection rates among women.

Even though the fatality rates of women below age 60 are low, engagement in care-work poses a higher risk to healthcare workers and care-home staff. This factor should be included in the ongoing discussions on the impact of COVID-19 on women’s health and wellbeing.

COVID-19 infection rates by age and sex per 1,000 population (solid line for females, dashed line for males, left-hand axis) and the relative M/F ratio in infection rates by age in four European countries

This blogpost is based on the following paper:

Sobotka T, Brzozowska Z, Muttarak R, Zeman K, & di Lego V (2020). Age, gender and COVID-19 infections. medRxiv 2020.05.24.20111765. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.24.20111765

References

Global Health 5050. COVID-19 sex-disaggregated data tracker. https://globalhealth5050.org/covid19/ (accessed May 18, 2020)

Ducharme J. Why Is COVID-19 Striking Men Harder Than Women? Time, 1 May 2020. https://time.com/5829202/covid-19-gender-differences/

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jun 3, 2020 | COVID19, Health, Science and Policy, Women in Science

By Nicole Arbour, external relations manager in the IIASA Communications and External Relations department

As Canadian expats in Austria, one of the things that has particularly struck my family and I is the orderliness with which the country is dealing with the pandemic. As quarantine policies were put into place, we saw panic toilet paper hoarding in other countries, but here in Austria people were (amazingly) compliant and seemed to obey instructions and timelines provided by the authorities. We never worried about our basic needs. Grocery stores were always well stocked, public transit was always there and on time – and masks were readily available when required as physical barrier to protect others.

© Luca Santilli | Dreamstime.com

Expert opinions, governments, and publics are making it clear that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to this pandemic. What works in Austria might not be what worked for South Korea; and likely not the same as what works in other parts of Europe. Consider the Canadian landscape. There is huge variation in sociopolitical and cultural dynamics between and within provinces and territories. What works for some parts of Canada (virtual home schooling, grocery shopping) is impossible for others (Canada’s North). Cultural norms (multigenerational living, child/elder care) vary across the vast landscape. The “At Home on the Land” initiative – aimed at the particular needs of Indigenous communities is an example of a culturally-grounded way to address the pandemic. Finding solutions isn’t always as intuitive as we might like.

Humans tend to look for the easiest way out – we want simple solutions to complex problems. We don’t seem to want to think about the problems, we want them magically disappear. And thinking “outside of the box” isn’t always appreciated. Hand washing, clean water and the advent of antibiotics have made enormous leaps in our ability to tackle public health outbreaks – significant results. Where the bubonic plague is estimated to have killed 30%-60% of Europe’s population in the Middle Ages, modern outbreaks are now quickly identified and contained (were you even aware of the 2017 outbreak in Madagascar?). Understanding transmission routes has significantly impacted public health outcomes. The identification of tainted water as a vector for cholera transmission by John Snow led to the advent of modern epidemiology. But, as we find solutions to larger challenges, those that remain are more complex with increasing numbers of variables making solutions harder to come by.

There is some global agreement: lots of testing, quick results/containment, use of masks/physical barriers for community protection, social distancing, data collection. However, certain measures work better in some jurisdictions than others. What policies and practices are working and why are they working in these contexts? What is applicable in different contexts?

Our current global situation, has reminded me of a presentation I saw on the 2014 Ebola outbreak (Professor Melissa Leach, IDS), and how important it is to remember the human factor in crises. She discussed how the key elements that made the Ebola pandemic so persistent – despite the best efforts of global public health engagement – was a/the failure to understand how historic context, trust, cultural dynamics played into the spread of the virus. Those providing interventions did not appreciate how historic context (i.e. post-colonialism, slavery, medical testing scandals) and mistrust in the intentions of Western interventions factored into the willingness of the local population to accept the solutions provided. Awareness of social structures, influencers and leaders, and co-creation were also important to developing solutions that would be adopted by affected communities.

Evidence is more than the numbers of tests, infections and deaths. It is understanding the social context of communities, society writ large, and how they interact within and between. It’s about understanding historical context and how it feeds into local culture, social interactions and trust relationships. It’s about community dynamics, power struggles and the struggle for some to meet basic survival needs. It’s about timing of decision-making, political landscapes and different ways of leading. As with many of our global challenges, it’s a complex and multifaceted systems problem – in which the human factor is a huge driver.

As we strive for solutions to this global crisis – bring on innovation, research and science funding. We will need these – but please, also bring along those who study the complexity that is humanity: epidemiologists, anthropologists, economists, ethicists, political scientists, sociologists, futurists, etc. In an era where evidence is being questioned, fake news is rampant and anti-science sentiments are strong, it is crucial that we remember that one piece to engaging with this and the world’s other wicked problems is our relationships with our communities – the ones we are trying to protect. Public trust, built on understanding of the importance of human dynamics is key to broad acceptance and uptake. Solutions need to be palatable to society, or they won’t be adopted.

As we focus on the virus, let’s not forget the humans.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. Link to original post: https://sciencepolicy.ca/news/save-covid19-lets-not-forget-humans

Apr 29, 2020 | Austria, COVID19, Systems Analysis

By Tamás Krisztin, researcher in the IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Tamás Krisztin discusses the air travel restrictions instituted by governments across the globe and how effective they really are in terms of curbing the spread of COVID-19.

© Potowizard | Dreamstime.com

Many Western countries are reaching, or have reached, the peak of COVID-19 infections, and policymakers are increasingly turning their attention to the next critical question: how to lift lockdown restrictions responsibly, while at the same time making sure that trade and travel can be restored to as close to “normal” as possible? Our research indicates that stoppage of airline traffic and border closures, which were some of the first modes of transport to be restricted, should also be some of the last to be restored because of their critical role in spreading infections.

Governments began to restrict airline traffic at the end of January this year, and by 21 March, over half of the EU had implemented flight suspensions. Our research confirms that this was a timely and necessary step. In the early stages of the pandemic, international flight linkages were actually the main transmission channel for the virus. In fact, flight connections proved to be an even more accurate predictor of infection spread between two countries than the presence of common land borders or trade connections. As country after country enacted travel bans, our research also shows a corresponding decrease in cross-country spillovers of the virus.

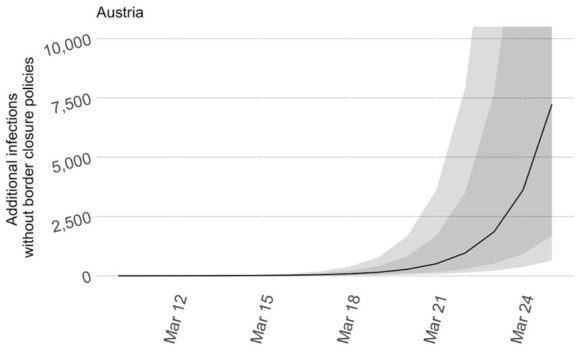

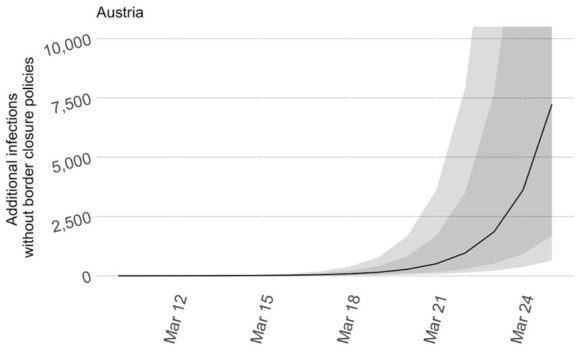

In Austria, for instance, our model demonstrates that if the shutdown of cross border traffic (flight connections and car border crossings) had been delayed by only 16 days, (25 March instead of 10 March), about 7,200 additional people would have been infected (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Additional infections in Austria without border closures (Note: Shaded areas correspond to the 68th and 90th quantiles, respectively).

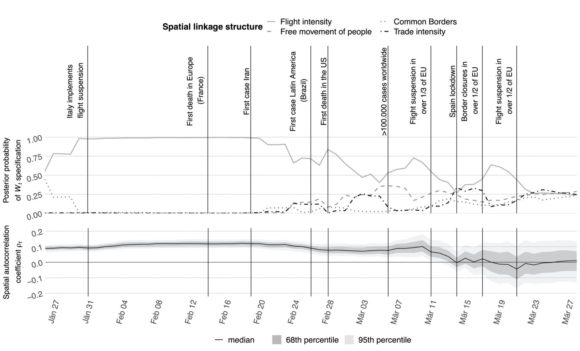

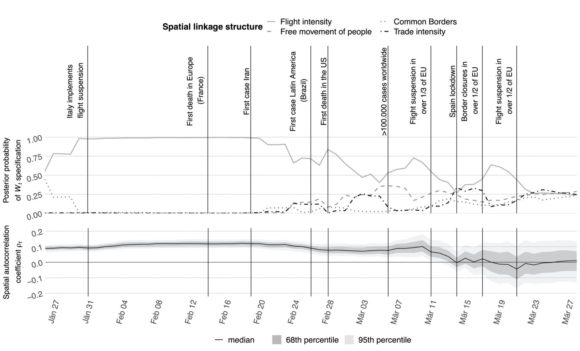

Additionally, our modeling shows the increased importance of flight connections over the initial period of the crisis, as seen in Figure 2. The top panel visualizes the relative importance of connectivity measures and demonstrates that, particularly in the beginning phases of the pandemic, flight connections were of the highest importance. The bottom panel shows infection spread between countries. Around the middle of March, when most border closure policies were implemented, the line drops to zero, indicating that these measures significantly reduced cross-border infections.

Figure 2: Importance of connectivity (top panel) and spatial spillovers (bottom panel)

Given the importance of air travel as a means for transmission of COVID-19, it stands to reason that governments and policymakers will have to continue to restrict air travel to prevent a second wave of the virus. As some parts of the world begin slowly to lift restrictions and ease lockdowns, while others are only now beginning to near the peak of the pandemic, it is likely that air travel will continue to be severely limited to prevent cross-border spread.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Apr 8, 2020 | Brazil, COVID19, Health, Women in Science

By Raquel Guimaraes, postdoc in the IIASA World Population Program

IIASA postdoc Raquel Guimaraes writes about efforts by the scientific community to encourage governments in Latin America and the Caribbean to increase COVID-19 test coverage to reduce vulnerability.

© Kukhunthod | Dreamstime.com

Together with a group of demographers from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), and endorsed by more than 250 individuals from the academic community, I contributed to a statement urging governments, the World Health Organization, and the Pan American Health Organization, to take immediate action to drastically increase the coverage of COVID-19 tests in the region. This call for action was disseminated by the British Society for Population Studies, Asociación Latino Americana de Población, Sociedad Mexicana de Demografía, Associação Brasileira de Estudos Populacionais, and the Population Association of America, among other important institutions.

I joined this initiative by invitation from Dr. Enrique Acosta and other colleagues, because I firmly believe that the prospects for the COVID-19 pandemic in the LAC region are rather dramatic. Several studies document that, apart from being globally recognized for its high levels of economic and social inequality, the region also suffers from institutional coordination failures and poor governance, a lack of appropriate resources, and presents a unique epidemiological and demographic profile of its population that escalates the negative prospects of the pandemic. I wanted to explore in more detail why these features of LAC are a source of major concern and require immediate action.

Social and economic inequality in LAC will hamper the enforcement of social distancing and isolation measures, which have proven to mitigate the COVID-19 epidemic in other settings. More than half of the population is in the informal labour market and does not have access to social safety nets. For those covered by the social security system, the benefits already proposed by a few governments of the region such as Brazil, fall short of the daily needs of families. In addition to economic inequality, social inequality, which leads to a high degree of cohabitation between adults and the elderly, increases the exposure of those with the highest risk of complications and death.

In addition, with the closure of schools, children who do not have access to day-care centres and the public- or private education system, often rely on the help of their grandparents, which again brings greater vulnerability to families. Not to mention that these children won’t have ensured their learning opportunities, because their parents are often working and not able to home-school them, thus compromising their education outcomes.

Moreover, LAC is facing a rapid demographic transition and aging process, which is temporarily increasing the prevalence of a young population, meaning that the population age-structure of potential infected individuals differs from that of other settings. However, unlike the more developed countries, LAC’s epidemiologic transition, that is, the transition in which the prevalence of infectious diseases is “substituted” by chronic and degenerative diseases, is not complete. Paradoxically, the region exhibits both the prevalence of diseases that have long been eradicated in more developed contexts (such as malaria, dengue, and tuberculosis) and diseases of richer countries (such as hypertension, diabetes, and neoplasms).

On top of all the above-mentioned vulnerabilities, crisis-management efforts in the region are uncoordinated, and lacking transparency and commitment. Taking Brazil as an example: while some mayors and governors adopt measures of social isolation and prevention against COVID-19, parts of the federal executive power not only disdain the problem, but encourages the population not to meet the requirements established by the Ministry of Health. Such conflicting rules are bound to cause misunderstandings among the LAC population. The COVID-19 pandemic is a crucial moment for institutional coordination to ensure the effective management of the crisis.

As an important and urgent call to action for the pandemic in the region, myself and other LAC researchers are calling for an increase in test coverage and measures of social isolation. As reported in the non-specialized media under the slogan “help to flatten the curve”, social isolation allows the rate of contagion of the virus to be reduced, in order to prevent overloading the capacity of the health system. Existing literature documents that while the virus does not cause major damage to health for the majority of infected persons, it brings a high cost to the health system. Furthermore, the impacts on the later lives of individuals who were hospitalized due to the disease are not yet known. Not to mention, of course, the human tragedy and the costs in terms of lives lost to the disease.

Finally, imperative and immediate action against COVID-19 in LAC will depend on the widespread and low-cost application of tests. This is required because the former rigorous isolation measures mentioned above are highly ineffective if not accompanied by aggressive strategies to detect cases of COVID-19. This highlights the relevance of data collection to better inform policymakers and provide researchers with clear diagnoses of the conditions in the region.

References:

Deaton A (2013). Cap. 3. Escaping death in the Tropics. In The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality. Princeton University Press.

Hoffman K, & Centeno MA (2003). The Lopsided Continent: Inequality in Latin America. Annual Review of Sociology, 29(1), 363–390. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100141

Khemani S, Ferraz C, Finan FS, Johnson S, Louise C, Abrahams SD, Odugbemi AM, Dal Bó E, & Thapa D (2016). Making politics work for development: Harnessing transparency and citizen engagement (Policy Research Report). The World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/268021467831470443/Making-politics-work-for-development-harnessing-transparency-and-citizen-engagement

Pérez CC, & Hernández AL (2007). Latin–American public financial reporting: Recent and future development. Public Administration and Development, 27(2), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.441

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Mar 10, 2020 | COVID19, Health, IIASA Network, Wellbeing, Women in Science

Raya Muttarak, Deputy Program Director, IIASA World Population Program

Raya Muttarak writes about what we have learnt about the COVID-19 outbreak so far, and how collective mitigation measures could influence the spread of the disease.

© Konstantinos A | Dreamstime.com

Since the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China back in January, we have learnt a lot about the virus: we know how to detect the symptoms, and a vaccination is currently being developed. However, there are still many uncertainties:

We for example don’t know enough about the disease’s fatality rate – mainly because we don’t precisely know how many people are infected, which is the denominator. We also don’t know exactly how the virus spreads. Generally, it is assumed that the virus spreads from person-to-person through close contact (within about 1 meter) and through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes. It is also thought that COVID-19 can spread from contact with contaminated surfaces or objects.

In addition, knowledge about the timing of infectiousness is still uncertain. There is evidence that the transmission can happen before the onset of symptoms, although it is commonly thought that people are most contagious when they are most symptomatic. This information is crucial, because if we know the timing patterns of the transmission, we could adopt better measures around when to quarantine an infected person.

Lastly, we don’t yet know whether the spread of the disease will slow down once the weather gets warmer.

What is currently happening in Iran, Italy, Japan, and South Korea may be unique to these countries, but it is more than likely that most countries will eventually experience the spread of COVID-19. In this regard, epidemiologists have estimated that in the absence of mitigation measures, in the worst-case scenario, approximately 60% of the population would become infected. In February, Nancy Messonnier, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Centre for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases in the US, warned that “It’s not so much of a question of if this will happen anymore, but rather more of a question of exactly when this will happen.”

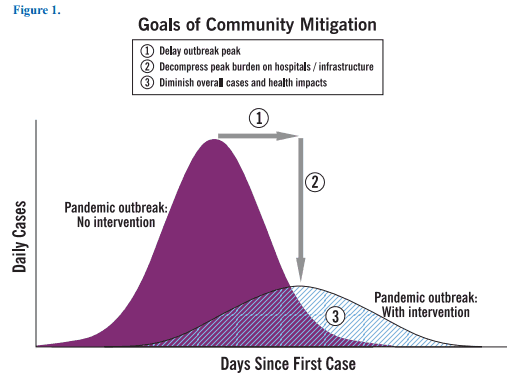

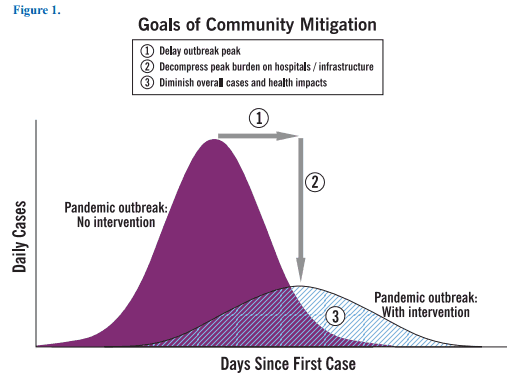

We learnt from an epidemiological transmission model that public efforts to curb the transmission of the disease should be directed towards flattening the epidemic curve. This is crucial, since the treatment of severe lung failure caused by COVID-19 requires ventilators to help patients breathe in intensive care units (ICUs). Not a single country in the world has the capacity to absorb the large number of people who would need intensive care at the same time. Experience from Italy shows that about 10% of all patients who test positive for COVID-19 require intensive care. Although efforts have been made to increase ICU capacity, the rapidly growing number of infected patients is overloading the healthcare system. Measures to reduce transmission in order to slow down the epidemic over the course of the year will therefore significantly mitigate the impact of COVID-19.

A transmission model with and without intervention.

Source: CDC. (2007). Interim Pre-pandemic Planning Guidance: Community Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Mitigation in the United States—. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The figure above shows the distribution of infectious cases with and without intervention. If the outbreak peak can be delayed, this allows the health system and healthcare professionals to bring the number of persons that require hospitalization and intensive care in line with the nation’s capacity to provide medical care. To flatten the epidemic curve and lower peak morbidity and mortality, calls for both government response and individual actions.

We will have to follow the protocol of the Austrian Health Ministry, but certain practices such as social distancing, washing hands, and avoiding gathering in crowded places, can help reduce the transmission of the disease. While it is true that young and healthy people are less likely to get sick and die from COVID-19, they can still be a virus carrier and thus transmit the disease to other vulnerable subgroups of the population, such as older people and those with underlying health conditions. An article recently published in The Lancet provides helpful information to better understand the current situation and explains why fighting against COVID-19 will take collective action.

Reference:

Anderson R, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, & Hollingsworth T (2020). How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet 0(0) DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.