Jul 11, 2019 | IIASA Network, USA, Women in Science

Rachel Potter, IIASA communications officer, interviews retired NASA Astronaut and Principal of AstroPlanetview LLC, Sandra H Magnus on insights about our world she has gained from her time living on the International Space Station.

©NASA Photo / Houston Chronicle, Smiley N. Pool

Q: Can you tell us a bit about your specific areas of research as a scientist?

A: My PhD was on a new material system being investigated for thermionic cathodes, which are used as electron sources for satellite communication systems. My research was an effort to look at the system methodically and from a science viewpoint to understand physically what was going on in order to inform the design of more robust devices. If you can operate the cathode at a lower temperature, that means a longer life for it, which is a good thing for satellites! Post-PhD I was however admitted to the Astronaut Office and that, quite frankly, pretty much put an end to my career as a researcher, or at least as a principal investigator (PI). The work I did on the International Space Station was at the direction of other PIs who had proposed, and been granted, experiments in space.

Q: Your career has spanned a wide range of settings from the NASA Astronaut Corps to your current role as Principal of AstroPlanetview LLC – what is the common thread or focus that has run through your work?

A: Following my curiosity and looking for challenges. I always want to be challenged and feel that I am learning new things. If I feel that I have become stagnant, I start looking for how to change that situation.

Q: What have been the personal highlights of your career?

A: Clearly flying in space! I feel very fortunate, however, to have been in the Astronaut Office during the era of the space station. I enjoyed very much working in a collaborative, multicultural, international environment where we had a big team of people from around the world working on something that benefits the planet.

Q: What are the greatest lessons you have learned from seeing the Earth from space?

A: I was so excited to FINALLY be going into space after hoping to do just that for over 20 years. The Earth is our spaceship – a closed system in which everything on the planet affects, and is connected to everything else on the planet. An action somewhere means a reaction somewhere else, even if it is not always first order (and usually it is not). Also, the planet looks incredibly beautiful and very fragile – we have to take care of it!

© NASA STS-126 Shuttle Mission full crew photo (5 March 2008), Sandra H Magnus far left.

Q: What do you see as key to solving the complex problems the Earth faces in terms of sustainability?

A: Having the will to do it as a community. If you have the will, commitment and a clear, agreed-to, articulation of the common goal, we can pretty much accomplish anything we want to.

Q: How do you see IIASA being able to build bridges between countries across political divides?

A: Well, when we want to solve problems, it really is all about relationships at the end of the day. It is easy to demonize or keep your distance from abstract ideas or the ubiquitous “They” but when you meet people, understand them as individuals and the context of their backgrounds that lead them to have different views and approaches to life and solving problems, it is much easier to visualize how you can work together to tackle issues. The relationships are the bridges.

Q: What advice would you give to young women researchers wanting to make it into Aeronautics?

A: To young women (and young men, too, really) I would say, “If you have a dream to go do something, then you owe it to yourself to go for it and try it!” Never let anyone else define who you are or tell you what you can or cannot do – believe in yourself and give it a try. Maybe you will make it, maybe you will not, but it will be on your own terms, with you pushing yourself and regardless of the outcome you will have a deeper understanding of yourself, and that is always a good thing.

Sandra H Magnus visited IIASA on 21 June 2019 in cooperation with the US Embassy Vienna, to give a lecture entitled “Perspectives from Space” to IIASA staff and this year’s participants of the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program. IIASA has a worldwide network of collaborators who contribute to research by collecting, processing, and evaluating local and regional data that are integrated into IIASA models. The institute has 819 research partner institutions in member countries and works with research funders, academic institutions, policymakers, and individual researchers in national member organizations.

Notes:

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 29, 2019 | Science and Policy, Vietnam

Tran Thi Vo-Quyen, IIASA guest research scholar from the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (VAST), talks to Professor Dr. Ninh Khac Ban, Director General of the International Cooperation Department at VAST and IIASA council member for Vietnam, about achievements and challenges that Vietnam has faced in the last 5 years, and how IIASA research will help Vietnam and VAST in the future.

Professor Dr. Ninh Khac Ban, Director General of the International Cooperation Department at VAST and IIASA council member for Vietnam

What have been the highlights of Vietnam-IIASA membership until now?

In 2017, IIASA and VAST researchers started working on a joint project to support air pollution management in the Hanoi region which ultimately led to the successful development of the IIASA Greenhouse Gas – Air Pollution Interactions and Synergies (GAINS) model for the Hanoi region. The success of the project will contribute to a system for forecasting the changing trend of air pollution and will help local policy makers develop cost effective policy and management plans for improving air quality, in particular, in Hanoi and more widely in Vietnam.

IIASA capacity building programs have also been successful for Vietnam, with a participant of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) becoming a key coordinator of the GAINS project. VAST has also benefited from two members of its International Cooperation Department visiting the IIASA External Relations Department for a period of 3 months in 2018 and 2019, to learn about how IIASA deals with its National Member Organizations (NMOs) and to assist IIASA in developing its activities with Vietnam.

What do you think will be the key scientific challenges to face Vietnam in the next few years? And how do you envision IIASA helping Vietnam to tackle these?

In the global context Vietnam is facing many challenges relating to climate change, energy issues and environmental pollution, which will continue in the coming years. IIASA can help key members of Vietnam’s scientific community to build specific scenarios, access in-depth knowledge and obtain global data that will help them advise Vietnamese government officials on how best they can overcome the negative impact of these issues.

As Director General of the International Cooperation Department, can you explain your role in VAST and as representative to IIASA in a little more detail?

In leading the International Cooperation Department at VAST, I coordinate all collaborative science and technology activities between VAST and more than 50 international partner institutions that collaborate with VAST.

As the IIASA council representative for Vietnam, I participate in the biannual meeting for the IIASA council, I was also a member of the recent task force developed to implement the recommendations of a recent independent review of the institute. I was involved in consulting on the future strategies, organizational structure, NMO value proposition and need to improve the management system of IIASA.

In Vietnam, I advised on the establishment of a Vietnam network for joining IIASA and I implement IIASA-Vietnam activities, coordinating with other IIASA NMOs to ensure Vietnam is well represented in their countries.

You mentioned the development of the Vietnam-IIASA GAINS Model. Can you explain why this was so important to Vietnam and how it is helping to improve air quality and shape Vietnamese policy around air pollution?

Air pollution levels in Vietnam in the last years has had an adverse effect on public health and has caused significant environmental degradation, including greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, undermining the potential for sustainable socioeconomic development of the country and impacting the poor. It was important for Vietnam to use IIASA researchers’ expertise and models to help them improve the current situation, and to help Vietnam in developing the scientific infrastructure for a long-lasting science-policy interface for air quality management.

The project is helping Vietnamese researchers in a number of ways, including helping us to develop a multi-disciplinary research community in Vietnam on integrated air quality management, and in providing local decision makers with the capacity to develop cost-effective management plans for the Hanoi metropolitan area and surrounding regions and, in the longer-term, the whole of Vietnam.

About VAST and Ninh Khac Ban

VAST was established in 1975 by the Vietnamese government to carry out basic research in natural sciences and to provide objective grounds for science and technology management, for shaping policies, strategies and plans for socio-economic development in Vietnam. Ninh Khac Ban obtained his PhD in Biology from VAST’s Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources in 2001. He has managed several large research projects as a principal advisor, including several multinational joint research projects. His successful academic career has led to the publication of more than 34 international articles with a high ranking, and more than 60 national articles, and 2 registered patents. He has supervised 5 master’s and 9 PhD level students successfully to graduation and has contributed to pedagogical texts for postgraduate training in his field of expertise.

Notes:

More information on IIASA and Vietnam collaborations. This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 16, 2018 | Alumni, Climate Change, Environment, Science and Policy, Women in Science, Young Scientists

Laura Mononen experiencing a creative ”world flow” in the art installation ‘Passage’ by Matej Kren in Bratislava | © Kati Niiles

By Sandra Ortellado, IIASA 2018 Science Communication Fellow

If fashion is the science of appearances, what can beauty and aesthetics tell us about the way we perceive the world, and how it influences us in turn?

From cognitive science research, we know that aesthetics not only influence superficial appearances, but also the deeper ways we think and experience. So, too, do all kinds of creative thinking create change in the same way: as our perceptions of the world around us changes, the world we create changes with them.

From the merchandizing shelves of H&M and Vero Moda to doctoral research at the Faculty of Information Technology at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland, 2018 YSSP participant Laura Mononen has seen product delivery from all angles. Whether dealing with commercialized goods or intellectual knowledge, Mononen knows that creativity is all about a change in thinking, and changing thinking is all about product delivery.

“During my career in the fashion and clothing industry, I saw the different levels of production when we sent designs to factories, received clothing back, and then persuaded customers to buy them. It was all happening very effectively,” says Mononen.

But Mononen saw potential for product delivery beyond selling people things they don’t need. She wanted to transfer the efficiency of the fashion world in creating changes in thinking to the efforts to build a sustainable world.

“Entrepreneurs make change with products and companies, fashion change trends and sell them. I’m really interested in applying this kind of change to science policy and communication,” says Mononen. “We treat these fields as though they are completely different, but the thing that is common is humans and their thinking and behaving.”

Often, change must happen in our thinking first before we can act. That’s why Mononen is getting her doctorate in cognitive science. Her YSSP project involved heavy analysis of systems theories of creativity to find patterns in the way we think about creativity, which has been constantly changing over time.

In the past, creativity was seen as an ability that was characteristic of only certain very gifted individuals. The research focused on traits and psychological factors. Today, the thinking on creativity has shifted towards a more holistic view, incorporating interactions and relationships between larger systems. Instead of being viewed as a lightning bolt of inspiration, creativity is now seen as more of a gradual process.

New understandings of creativity also call on us to embrace paradoxes and chaos, see ourselves as part of nature rather than separate from it, experience the world through aesthetics, pay careful attention to our perception and how we communicate it, and transmit culture to the next generation.

Perhaps most importantly, Mononen found in her research that the understanding of creativity has changed to be seen as part of a process of self-creation as well as co-creation.

“The way we see creativity also influences ourselves. For example if I ask someone if they are creative, it’s the way they see themselves that influences how creative they are,” says Mononen. “I have found that it’s more crucial to us than I thought, creativity is everywhere and it’s everyday and we are sharing our creativity with others who are using that to do something themselves and so on.”

This means on the one hand that we use our creativity to decide who we are and how we see the world around us for ourselves. But it also means that the outcomes and benefits of creativity are now intended for society as a whole rather than purely for individuals, as it was in the past. It may sound like another paradox, but being able to embrace ambiguity and complexity and take charge of our role in a larger system is important for creating a sustainable future.

“From the IIASA perspective this finding brings hope because the more people see themselves as part of systems of creating things, the more we can encourage sustainable thinking, since nature is a part of the resources we use to create,” says Mononen.

Mononen says a systems understanding of creativity is especially important for people in leadership positions. If a large institution needs new and innovative solutions and technology, but doesn’t have the thinking that values and promotes creativity, then the cooperative, open-minded process of building is stifled.

Working in both the fashion industry and academic research, Mononen has encountered narrow-minded attitudes towards art and science firsthand.

“Communicating your research is very difficult coming from my background, because you don’t know how the other person is interpreting what you say,” says Mononen. “People have different ideas of what fashion and aesthetics are, how important they are and what they do. Additionally, scientific concepts are used differently in different fields.”

“We are often thinking that once we get information out there, then people will understand, but there are much more complex things going on to make change and create influence in settings that combine several different fields.” says Mononen.

For Mononen, the biggest lesson is that creativity can enhance the efforts of science towards a sustainable world simply by encouraging us to be aware of our own thinking, how it differs from that of others, and how it affects all of us.

“When you become more aware of your ways of thinking, you become more effective at communicating,” says Mononen. “It’s not always that way and it’s very challenging, but that’s what the research on creativity from a systems perspective is saying.”

Jul 9, 2018 | Alumni, Communication, IIASA Network, South Africa, Systems Analysis, Young Scientists

By Sandra Ortellado, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2018

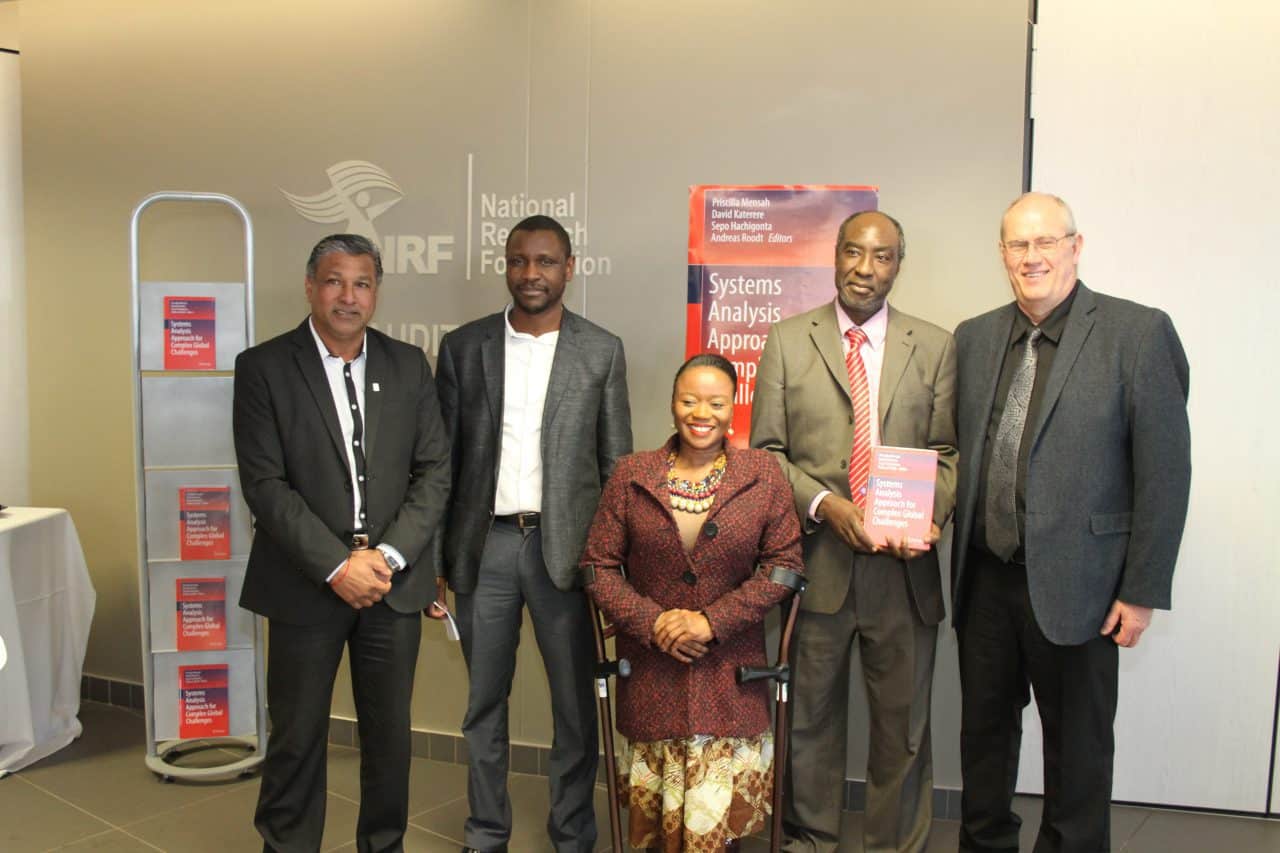

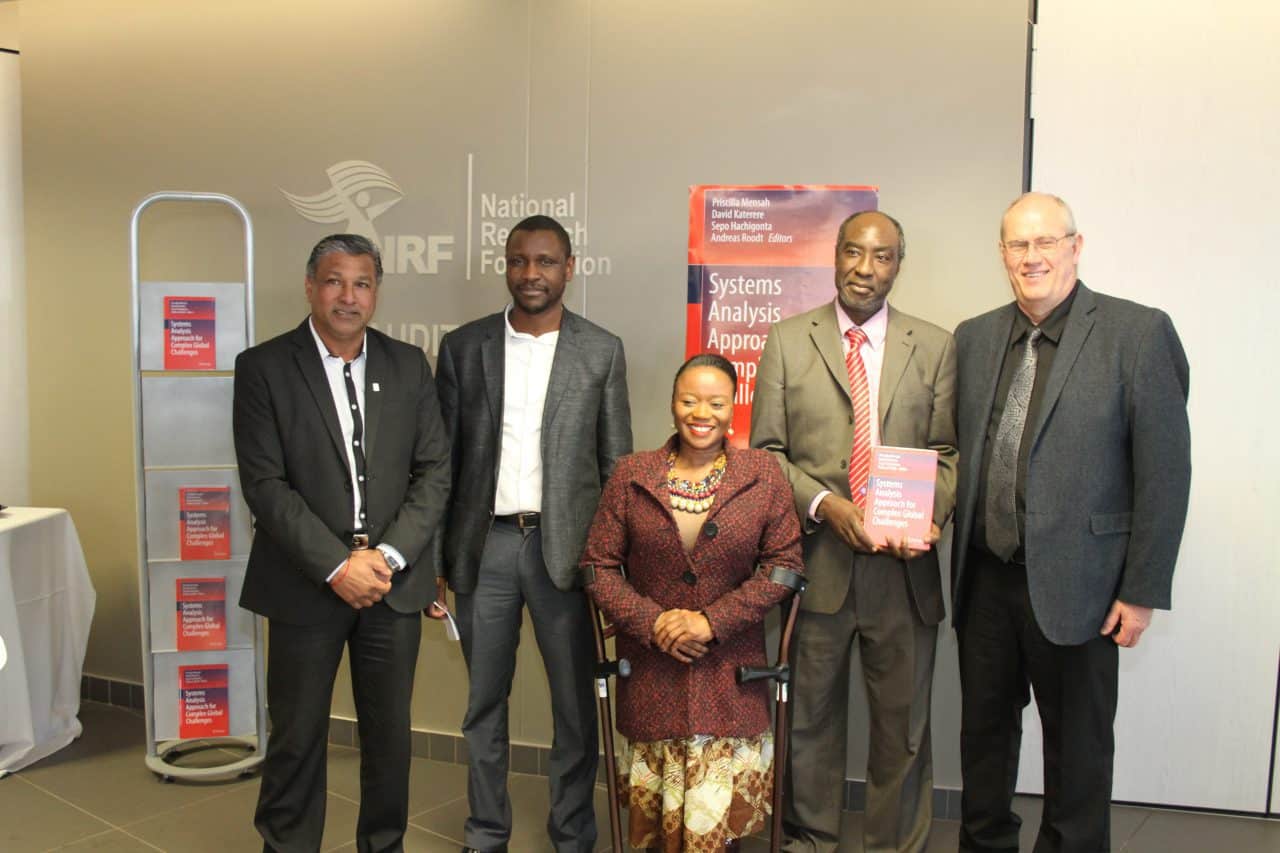

In 2007, Sepo Hachigonta was a first-year PhD student studying crop and climate modeling and member of the YSSP cohort. Today, he is the director in the strategic partnership directorate at the National Research Foundation (NRF) in South Africa and one of the editors of the recently launched book Systems Analysis for Complex Global Challenges, which summarizes systems analysis research and its policy implications for issues in South Africa.

From left: Gansen Pillay, Deputy Chief Executive Officer: Research and Innovation Support and Advancement, NRF, Sepo Hachigonta, Editor, Priscilla Mensah, Editor, David Katerere, Editor, Andreas Roodt Editor

But the YSSP program is what first planted the seed for systems analysis thinking, he says, with lots of potential for growth.

Through his YSSP experience, Hachigonta saw that his research could impact the policy system within his home country of South Africa and the nearby region, and he forged lasting bonds with his peers. Together, they were able to think broadly about both academic and cultural issues, giving them the tools to challenge uncertainty and lead systems analysis research across the globe.

Afterwards, Hachigonta spent four years as part of a team leading the NRF, the South African IIASA national member organization (NMO), as well as the Southern African Young Scientists Summer Program (SA-YSSP), which later matured into the South African Systems Analysis Centre. The impressive accomplishments that resulted from these programs deserved to be recognized and highlighted, says Hachigonta, so he and his colleagues collected several years’ worth of research and learning into the book, a collaboration between both IIASA and South African experts.

“After we looked back at the investment we put in the YSSP, we had lots of programs that were happening in South Africa, and lots of publications and collaboration that we wanted to reignite,” said Hachigonta. “We want to look at the issues that we tackled with system analysis as well as the impact of our collaborations with IIASA.”

Now, many years into the relationship between IIASA and South Africa, that partnership has grown.

Between 2012 and 2015, the number of joint programs and collaborations between IIASA and South Africa increased substantially, and the SA-YSSP taught systems analysis skills to over 80 doctoral students from 30 countries, including 35 young scholars from South Africa.

In fact, several of the co-authors are former SA-YSSP alumni and supervisors turned experts in their fields.

“We wanted to use the book as a barometer to show that thanks to NMO public entity funding, students have matured and developed into experts and are able to use what they learned towards the betterment of the people,” says Hachigonta. The book is localized towards issues in South Africa, so it will bring home ideas about how to apply systems analysis thinking to problems like HIV and economic inequality, he adds.

“It’s not just a modeling component in the book, it still speaks to issues that are faced by society.”

Complex social dilemmas like these require clear and thoughtful communication for broader audiences, so the abstracts of the book are organized in sections to discuss how each chapter aligns systems analysis with policymaking and social improvement. That way, the reader can look at the abstract to make sense of the chapter without going into the modeling details.

“Systems analysis is like a black box, we do it every day but don’t learn what exactly it is. But in different countries and different sectors, people are always using systems analysis methodologies,” said Hachigonta, “so we’re hoping this book will enlighten the research community as well as other stakeholders on what systems analysis is and how it can be used to understand some of the challenges that we have.”

“Enlightenment” is a poetic way to frame their goal: recalling the age of human reason that popularized science and paved the way for political revolutions, Hachigonta knows the value of passing down years of intellectual heritage from one cohort of researchers to the next.

“You are watching this seed that was planted grow over time, which keeps you motivated,” says Hachigonta.

“Looking back, I am where I am now because of my involvement with IIASA 11 years ago, which has been shaping my life and the leadership role I’ve been playing within South Africa ever since.”

Apr 26, 2018 | Communication

By Luke Kirwan, Open Access Manager at the IIASA Library

World Intellectual Property Day is celebrated annually on 26 April to bring a greater awareness of the role that intellectual property rights, such as copyright, patents, and industrial designs play in encouraging innovation and creativity. Unlike traditional property, intellectual property is intangible. It is far harder to protect one’s intellectual property from infringement or copying than it is to protect physical property. Intellectual property rights are important as, when well implemented, they provide the creator sufficient protection to benefit from their creation, but aren’t so stringent that they prevent widespread use.

Intellectual property refers to an individual’s original, intellectual creations, whether that is scientific, artistic, technical, or otherwise. As with other types of property, your intellectual property is covered by certain rights and protections automatically granted to the creator. These convey upon the owner rights over the control and utilization of their intellectual output. Depending on the situation, your intellectual property rights will also be covered by one or more types of protection, varying from patents to trademarks. These types of protection are intended to prevent unauthorized use or piracy of intellectual property, and to confer upon the creator time-limited, exclusive rights to their intellectual output.

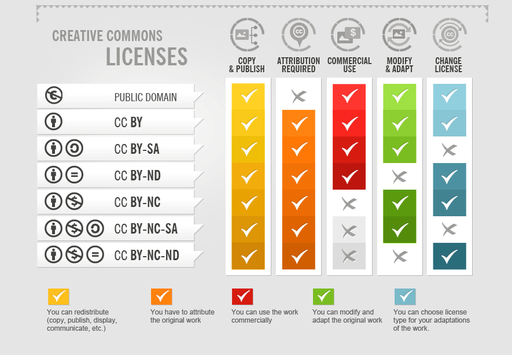

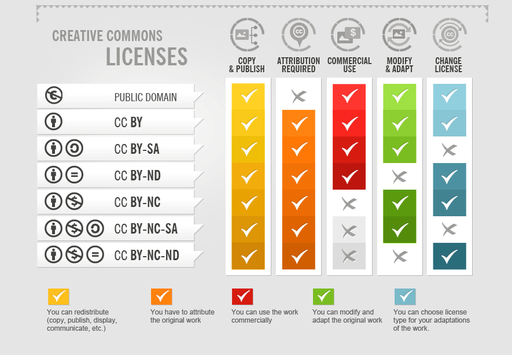

Creative commons licenses

When you write an article, that type of intellectual output is automatically covered by copyright. This is regulated through the Berne Convention. This convention confers a number of rights to the author, including the right to translate, make adaptations, and make reproductions of a work. Depending on the specific jurisdiction in which a work is created, copyright protection lasts for the lifetime of the creator plus a specific period (circa 50 to 70 years). In terms of producing a scientific article, one of the most important rights conferred upon an author by copyright protections is the right to sell or transfer these rights to another individual. Usually, when an author publishes an article with a journal, they sign a contract ceding their copyright to the publisher. Depending on the individual publisher, the author may retain some rights, such as the ability to distribute an earlier version of their paper and the right to proper attribution. However, the journal now has control of the dissemination, distribution, translation, and reproduction rights, among others.

Creative Commons licenses are designed to assist you in keeping your research openly accessible and distributable. For a creative commons license, the author retains all of the copyright, but has licensed their work for use and reuse under different circumstances, depending on the license. When publishing a paper under a creative commons license, rather than transferring the copyright to the publisher, the author instead licenses certain rights to the publisher to allow them to distribute the work. Creative commons licenses run from CC-0, which leaves a work completely free to reuse, redistribute, alter, and utilize in any manner, to CC-BY-NC-ND, which makes a work accessible, but restricts redistribution and commercial use. Similarly some license types employ an additional stipulation known as copyleft. In terms of a creative commons license this is known as share-alike. Essentially copyleft licensing allows people to freely distribute copies and modified versions as long as they adhere to the original licensing.

If you wish to make a paper open access, a journal will usually charge an Article Processing Charge (APC). However, the IIASA library maintains agreements with several publishers that allow a work to be made open access without charge. In instances where no waiver is in place, we also have an open access fund from which IIASA researchers can apply to have part of the APC charges paid for.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.