Oct 18, 2021 | Climate, Climate Change, Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Marina Andrijevic, researcher in the IIASA Energy, Climate, and Environment Program

Marina Andrijevic tackles some inconvenient but fundamental issues around climate change adaptation.

© Lio2012 | Dreamstime.com

Anyone who followed climate-related headlines this summer would have noticed a more than usual amount of talk on climate change adaptation. As it goes with sudden epiphanies in aftermaths of humanitarian disasters in our Western realities, this time we’ve come to realize that we need to seriously think about doing some adaptation.

To be fair, the realization that adaptation is inevitable has for a long time been somewhat of a taboo in the “woke” climate policy and activist circles (the author of this blog is a millennial and would like to acknowledge that the reader’s idea of a long time in climate policy might be different). Admitting that there might be no other option but to adapt to whatever the locked-in effects of climate change are, is arguably defeatist and gives in to the notion that mitigation alone won’t cut it.

While this might be yet another depressing but accurate reflection of the reality under climate change, portraying adaptation and mitigation as different but equally urgent actions could set a dangerous trap if it produces ideas such as: if we adapt enough, perhaps our economies and energy systems won’t need to change so much.

Even if it would be enough (which it wouldn’t), adaptation will not necessarily just happen once we recognize it needs to be done, because the needs and abilities for it operate on different time horizons and geographical scales. Many parts of the world that need adaptation will not necessarily be able to take action, so we have to be very careful when we count on it as a solution to climate change.

This is where we must tackle some inconvenient but fundamental issues about adaptation. Climate change research, especially the areas positioned at the “interface” with policy, could play a crucial role here. In this role, it must be very prudent and avoid doing a disservice to decision makers, and even worse, to people affected by those decisions. In other words, the scientific assessments need to be careful when assuming for whom, where, and how adaptation can reasonably be expected.

We tried to illustrate why this matters in our recent paper that looks at the capacity of populations to adapt to heat stress. We used air-conditioning as a popular, albeit not (yet) climate-friendly adaptation option. My coauthors and I understand that air conditioning could well be maladaptation, meaning that it causes more harm than good in the long-run. Adaptation practices, however, it turns out, are quite difficult to measure, while installed air conditioners can literally be counted, which makes them handy for plugging into our statistical models. We contend with access to air conditioning currently being a good enough example of access to adaptation and promise to assess more options in the future.

Our paper shows how the capacities to protect against heat stress vary widely around the world. Like with many other unjust manifestations of climate change, people in the world’s hottest areas also have the least means to adapt. We found that countries with more income, more urban areas, and less income inequality, are also the ones where more people have access to air conditioning.

This does not come as the world’s biggest revelation, but it conveniently allows us to make informed guesses on how access to air conditioning might change in 2050 or 2100. This is possible because the research community has already engaged in a group effort to propose five different futures with regard to GDP, urbanization, and income distribution (in climate jargon: the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways or SSPs).

Coupling the potential rates of air conditioning with the people exposed to heat stress based on projections of climate models, lets us calculate the cooling gap – the difference between people exposed to heat stress and people who can protect themselves against it with the use of air conditioning.

Depending on whether we find ourselves in the best- or the worst-case scenario of socioeconomic development could mean anywhere between two billion and five billion people globally unable to protect themselves against heat stress with air conditioning in 2050. This range only grows with longer time horizons, with Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia being the areas of the world where these differences are the starkest.

We hope that our paper will motivate further investigations of potential gaps in adaptation that point to insufficient adaptive capacity and help to identify the areas and populations most at risk, as well as what additional work needs to be done in terms of socioeconomic improvements before we can reasonably expect adaptation to take place. Our findings on the importance of factors beyond just GDP, suggest that helping communities to build their adaptive capacity doesn’t mean only throwing money at them (although that would make for a decent start!), but international efforts must focus on issues such as eradicating inequalities, supporting smart urban development, strengthening institutions, and providing education.

So, let’s not take it for granted that we will all be able to adapt either now or in the future. Eliminating the causes of climate change must remain the number one policy objective that will help to reduce the need for adaptation in the first place. But number two could be helping communities that have no option but to cope with what’s already coming at them. Highlighting in our research what the implications of different adaptive capacities are for preservation of livelihoods, is a small step towards achieving this.

Reference:

Andrijevic, M., Byers, E., Mastrucci, A., Smits, J., & Fuss, S. (2021). Future cooling gap in shared socioeconomic pathways. Environmental Research Letters 16 (9) e094053. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17411]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 18, 2021 | Austria, Climate, Climate Change, Communication, Education, Health

By Thomas Schinko, Acting Research Group Leader, Equity and Justice Research Group

Thomas Schinko introduces an innovative and transdisciplinary peer-to-peer training program.

What do we want – climate justice! When do we want it – now! The recent emergence of youth-led, social climate movements like #FridaysForFuture (#FFF), the Sunrise Movement, and Extinction Rebellion has reemphasized that at the heart of many – if not all – grand global challenges of our time, lie aspects of social and environmental justice. With a novel peer-to-peer education format, embedded in a transdisciplinary research project, the Austrian climate change research community responds to the call that unites these otherwise diverse movements: “Listen to the Science!”

The climate crisis raises several issues of justice, which include (but are not limited to) the following dimensions: First, intragenerational climate justice addresses the fair distribution of costs and benefits associated with climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as the rectification of damage caused by residual climate change impacts between present generations. Second, intergenerational justice focuses on the distribution of benefits and costs from climate change between present and future generations. Third, procedural justice asks for fair processes, namely that institutions allow all interested and affected actors to advance their claims while co-creating a low-carbon future. Movements like #FFF maneuver at the intersection of those three forms of climate justice when calling on policy- and decision makers to urgently take climate action, since “there is no planet B”.

Along with the emergence of these youth-led social climate movements came an increasing demand for the expertise of scientists working in the fields of climate change and sustainability research. To support #FFF’s claims with the best available scientific evidence, a group of German, Austrian, and Swiss scientists came together in early 2019 as Scientists for Future. Since then, requests from students, teachers, and policy and decision makers for researchers to engage with the younger generation have soared, also in Austria. Individual researchers like me have not been able to respond to all these requests at the extent we would have liked to.

In this situation of high demand for scientific support, the Climate Change Center Austria (CCCA) and The Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research (BMBWF) have put their heads together and established a transdisciplinary research project – makingAchange. By engaging early on with our potential end users – Austrian school students – a truly transdisciplinary team of researchers as well as practitioners in youth participation and education (the association “Welt der Kinder”) has co-developed this novel peer-to-peer curriculum. The training program, which runs over a full school year, sets out to provide the students not only with solid scientific facts but also with soft skills that are needed for passing on this knowledge and for building up their own climate initiatives in their schools and municipalities. One of the key aims is to provide solid scientific support while not overburdening the younger generation who often tend to put too high demands on themselves.

Establishing scientific facts about climate change and offering scientific projections of future change on its own does not drive political and societal change. Truly inter- and transdisciplinary research is needed to support the complex transformation towards a sustainable society and the integration of novel, bottom-up civil society initiatives with top-down policy- and decision making. Engaging multiple actors with their alternative problem frames and aspirations for sustainable futures is now recognized as essential for effective governance processes, and ultimately for robust policy implementation.

Also, in the context of makingAchange it is not sufficient to communicate science to students in order to generate real-world impact in terms of leading our societies onto low-carbon development pathways. What is additionally needed, is to provide them with complementary personal and social skills for enhancing their perceived self-efficacy and response efficacy, which is crucial for eventually translating their knowledge into real climate action in their respective spheres of influence.

Recent insights from a medical health assessment of the COVID-19 related lockdowns on childhood mental health in the UK have shown that we are engaging in an already highly fragile environment. In addition, a recent representative study for Austria has shown that the pandemic is becoming a psychological burden. The study authors are particularly concerned about young people; more than half of young Austrians are already showing symptoms of depression. Hence, we must engage very carefully with the makingAchange students when discussing the drivers and potential impacts of the climate crises. Particularly since some of them are quite well informed about research, which has shown (by using a statistical approach) that our chances of achieving the 1.5 to 2°C target stipulated in the Paris Agreement are now probably lower than 5%. Another example of such alarming research insights comes in the form of a 2020 report by the World Meteorological Organization, which warns that there is a 24% chance that global average temperatures could already surpass the 1.5°C mark in the next five years.

Zoom group picture taken at the end of the second online makingAchange workshop for Austrian school students. Copyright: makingAchange

The first makingAchange activities and workshops have now taken place – due to the COVID-19 regulations in an online format, which added further complexity to this transdisciplinary research project. Nevertheless, we were able to discuss some of the hot topics that the young people were curious about, such as the natural science foundations of the climate crisis, climate justice, or a healthy and sustainable diet. At the same time, we provided our students with skills to further transmit this knowledge and to take climate action in their everyday live – such as a climate friendly Christmas celebration in 2020. The school student’s lively engagement in these sessions as well as the overall positive (anonymous) feedback has proven that we are on the right track.

The role of science is changing fast from “advisor” to “partner” in civil society, policymaking, and decision making. By doing so, scientists can play an important, active role in implementing the desperately needed social-ecological transformation of our society without becoming policy prescriptive. With the makingAchange project, we are actively engaging in this transformational process – currently only in Austria but with high ambitions to scale-out this novel peer-to-peer format to other geographical and cultural contexts.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 26, 2020 | Alumni, Climate Change, History, USA, Young Scientists

By Marcus Thomson, IIASA alumnus and a researcher at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), the University of California, Santa Barbara

IIASA alumnus Marcus Thomson explains how what we have learnt about prehistoric farming cultures can be used to provide useful insights on human societal responses to climate change.

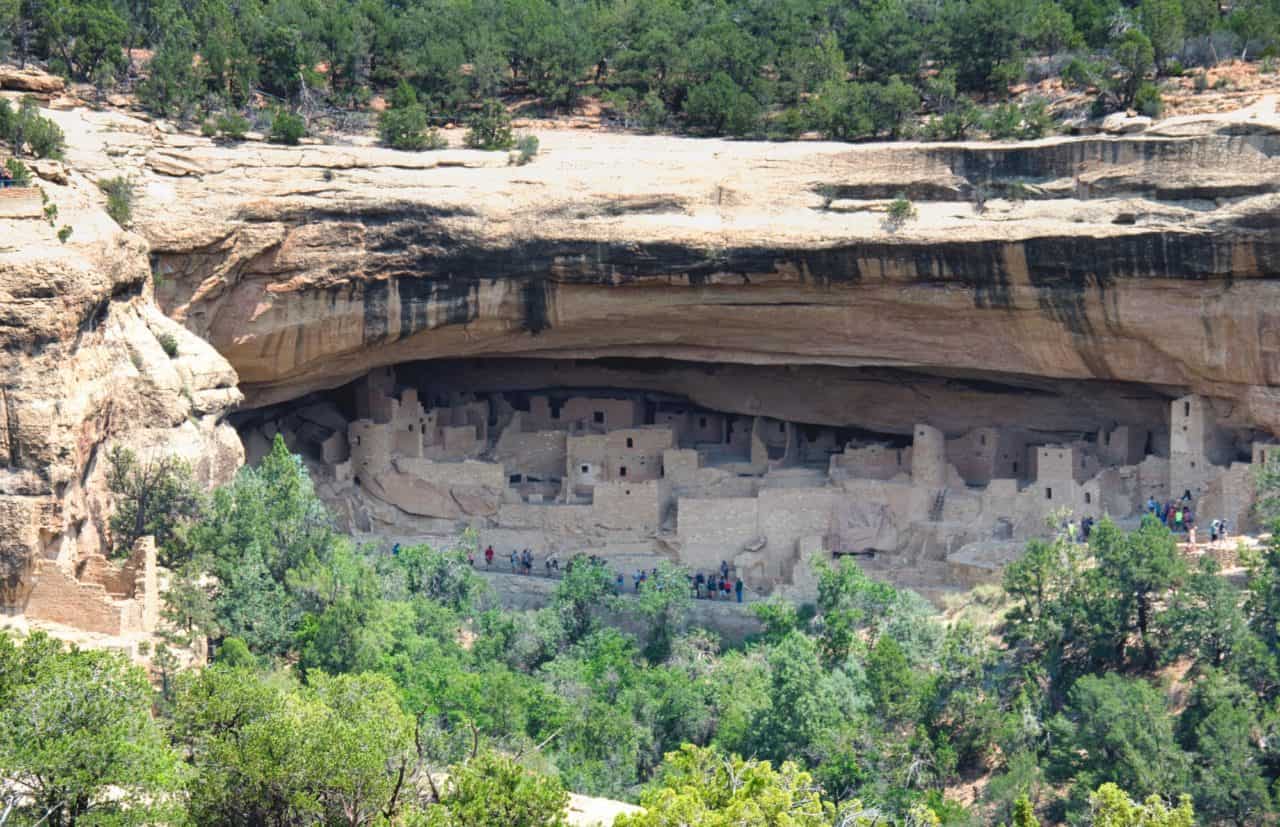

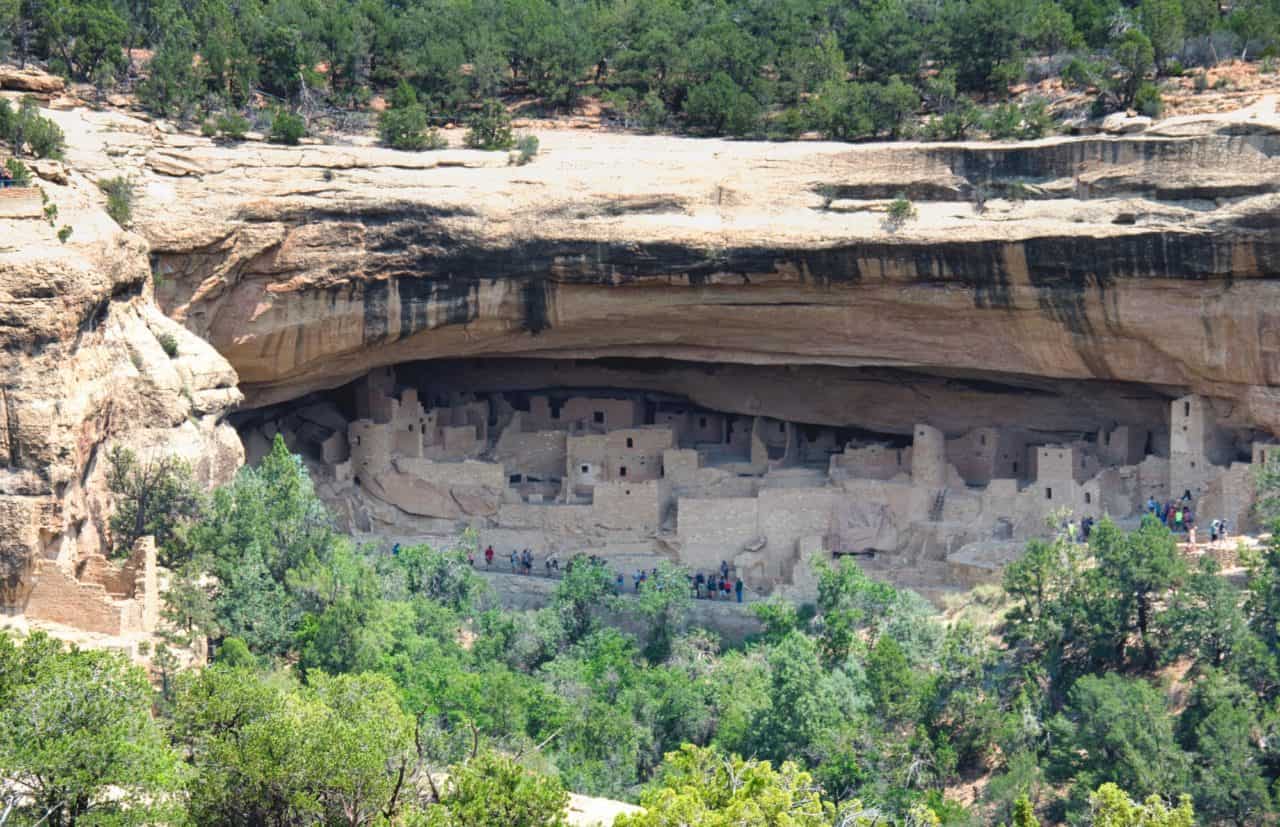

The climate of the western half of the North American continent, between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific coastal region, is dry by European standards. The American Southwest, in particular, centered roughly on the intersection of the states of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, is predominantly desert between high mountain plateaus. It is, and has always been, a challenging environment for farmers. Yet the prehistoric Southwest was home to complex maize-based agricultural societies. In fact, until the 19th century growth of industrial cities like New York, the Southwest contained ruins of the largest buildings north of Mexico — and these had been abandoned centuries before the Spanish arrived in the Americas.

© Mudwalker | Dreamstime.com

For more than a century, researchers have pored over data, from proxies of paleo-environmental change, to historiographies collected by explorers, to archaeology and computational models of human occupation, and produced a detailed picture of the socio-environmental, economic, and climatic conditions that could explain why these sites were abandoned. While details vary in fine-grained analyses of the various sub-groupings of peoples in the region, the big picture is one of societal transformation in adapting to climate change.

Also important is just how the climate changed during the period, because similar dynamics are expected to emerge in the future as a consequence of global warming. European historians point to a medieval era with generally warmer mean annual temperatures. In the Southwestern United States however, which is more sensitive to changes in drought than temperature, the period between roughly AD 850 to 1350 is known as the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA). The warm, dry MCA was followed by a long stretch of increased changes in the availability of water, known as the Little Ice Age (LIA). More frequent “warm droughts” at the end of the MCA, and generally increasing changes in water resources at the onset of the LIA, is thought to be a good analogy for future conditions in western North America.

When I had the good fortune to visit IIASA as a participant of the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) in 2016, I worked with research scholars Juraj Balkovič and Tamás Krisztin to develop a model of ancient Fremont Native American maize. The Fremont were an ancient forager-farmer people who lived in the vicinity of modern Utah. We used a climate model reconstruction of the temperature and rainfall between AD 850 and 1450 to drive this maize crop model, and compared modeled crop yields against changes in radiocarbon-derived occupations – in other words, the information gathered from carbon dated artifacts that show that an area was occupied by a particular people – from a few archaeological areas in Utah.

© Galyna Andrushko | Dreamstime.com

Among our findings was that changes in local temperatures appeared to play a larger role in the lives, practices and habits of the people who lived there than changes in regional, long-term temperature conditions [1]. Later, while a researcher at IIASA myself, I returned to the subject with one of our coauthors, professor Glen MacDonald of the University of California, Los Angeles, using an expanded geographic range and a more sophisticated treatment of radiocarbon dated occupation likelihoods.

We used the climate model to reconstruct prehistoric maize growing season lengths and mean annual rainfall for Fremont sites. We found that the most populous and resilient Fremont communities were at sites with low-variability season lengths; and low populations coincided with, or followed, periods of variable season lengths. This study confirmed the important dependence on climate variability; and more importantly, our results are in line with others on modern smallholder farming contexts.

More details on our latest study [2] have just been published online in Environmental Research Letters (ERL). It will become part of an ERL special issue looking at societal resilience drawing lessons from the past 5000 years. Studies like these can give useful insights on human societal responses to climate change because these ancient civilizations are, in a sense, completed experiments with complex human-environmental systems. For decision makers, who must plan early to commit resources to offset the effects of future climate change on smallholder farmers in similarly drought-sensitive, marginally productive environments, these studies indicate that year-to-year climatic variability drives occupation change more than long-term temperature change.

References:

[1] Thomson MJ, Balkovič J, Krisztin T, & MacDonald GM (2019). Simulated impact of paleoclimate change on Fremont Native American maize farming in Utah, 850–1449 CE, using crop and climate models. Quaternary International, 507, pp.95-107 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15472]

[2] Thomson MJ, & MacDonald GM (In press). Climate and growing season variability impacted the intensity and distribution of Fremont maize farmers during and after the Medieval Climate Anomaly based on a statistically downscaled climate model. Environmental Research Letters.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 29, 2019 | Science and Policy, Vietnam

Tran Thi Vo-Quyen, IIASA guest research scholar from the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (VAST), talks to Professor Dr. Ninh Khac Ban, Director General of the International Cooperation Department at VAST and IIASA council member for Vietnam, about achievements and challenges that Vietnam has faced in the last 5 years, and how IIASA research will help Vietnam and VAST in the future.

Professor Dr. Ninh Khac Ban, Director General of the International Cooperation Department at VAST and IIASA council member for Vietnam

What have been the highlights of Vietnam-IIASA membership until now?

In 2017, IIASA and VAST researchers started working on a joint project to support air pollution management in the Hanoi region which ultimately led to the successful development of the IIASA Greenhouse Gas – Air Pollution Interactions and Synergies (GAINS) model for the Hanoi region. The success of the project will contribute to a system for forecasting the changing trend of air pollution and will help local policy makers develop cost effective policy and management plans for improving air quality, in particular, in Hanoi and more widely in Vietnam.

IIASA capacity building programs have also been successful for Vietnam, with a participant of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) becoming a key coordinator of the GAINS project. VAST has also benefited from two members of its International Cooperation Department visiting the IIASA External Relations Department for a period of 3 months in 2018 and 2019, to learn about how IIASA deals with its National Member Organizations (NMOs) and to assist IIASA in developing its activities with Vietnam.

What do you think will be the key scientific challenges to face Vietnam in the next few years? And how do you envision IIASA helping Vietnam to tackle these?

In the global context Vietnam is facing many challenges relating to climate change, energy issues and environmental pollution, which will continue in the coming years. IIASA can help key members of Vietnam’s scientific community to build specific scenarios, access in-depth knowledge and obtain global data that will help them advise Vietnamese government officials on how best they can overcome the negative impact of these issues.

As Director General of the International Cooperation Department, can you explain your role in VAST and as representative to IIASA in a little more detail?

In leading the International Cooperation Department at VAST, I coordinate all collaborative science and technology activities between VAST and more than 50 international partner institutions that collaborate with VAST.

As the IIASA council representative for Vietnam, I participate in the biannual meeting for the IIASA council, I was also a member of the recent task force developed to implement the recommendations of a recent independent review of the institute. I was involved in consulting on the future strategies, organizational structure, NMO value proposition and need to improve the management system of IIASA.

In Vietnam, I advised on the establishment of a Vietnam network for joining IIASA and I implement IIASA-Vietnam activities, coordinating with other IIASA NMOs to ensure Vietnam is well represented in their countries.

You mentioned the development of the Vietnam-IIASA GAINS Model. Can you explain why this was so important to Vietnam and how it is helping to improve air quality and shape Vietnamese policy around air pollution?

Air pollution levels in Vietnam in the last years has had an adverse effect on public health and has caused significant environmental degradation, including greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, undermining the potential for sustainable socioeconomic development of the country and impacting the poor. It was important for Vietnam to use IIASA researchers’ expertise and models to help them improve the current situation, and to help Vietnam in developing the scientific infrastructure for a long-lasting science-policy interface for air quality management.

The project is helping Vietnamese researchers in a number of ways, including helping us to develop a multi-disciplinary research community in Vietnam on integrated air quality management, and in providing local decision makers with the capacity to develop cost-effective management plans for the Hanoi metropolitan area and surrounding regions and, in the longer-term, the whole of Vietnam.

About VAST and Ninh Khac Ban

VAST was established in 1975 by the Vietnamese government to carry out basic research in natural sciences and to provide objective grounds for science and technology management, for shaping policies, strategies and plans for socio-economic development in Vietnam. Ninh Khac Ban obtained his PhD in Biology from VAST’s Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources in 2001. He has managed several large research projects as a principal advisor, including several multinational joint research projects. His successful academic career has led to the publication of more than 34 international articles with a high ranking, and more than 60 national articles, and 2 registered patents. He has supervised 5 master’s and 9 PhD level students successfully to graduation and has contributed to pedagogical texts for postgraduate training in his field of expertise.

Notes:

More information on IIASA and Vietnam collaborations. This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 29, 2019 | USA, Young Scientists

By Matt Cooper, PhD student at the Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Maryland, and 2018 winner of the IIASA Peccei Award

I never pictured myself working in Europe. I have always been an eager traveler, and I spent many years living, working and doing fieldwork in Africa and Asia before starting my PhD. I was interested in topics like international development, environmental conservation, public health, and smallholder agriculture. These interests led me to my MA research in Mali, working for an NGO in Nairobi, and to helping found a National Park in the Philippines. But Europe seemed like a remote possibility. That was at least until fall 2017, when I was looking for opportunities to get abroad and gain some research experience for the following summer. I was worried that I wouldn’t find many opportunities, because my PhD research was different from what I had previously done. Rather than interviewing farmers or measuring trees in the field myself, I was running global models using data from satellites and other projects. Since most funding for PhD students is for fieldwork, I wasn’t sure what kind of opportunities I would find. However, luckily, I heard about an interesting opportunity called the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) at IIASA, and I decided to apply.

Participating in the YSSP turned out to be a great experience, both personally and professionally. Vienna is a wonderful city to live in, and I quickly made friends with my fellow YSSPers. Every weekend was filled with trips to the Alps or to nearby countries, and IIASA offers all sorts of activities during the week, from cultural festivals to triathlons. I also received very helpful advice and research instruction from my supervisors at IIASA, who brought a wealth of experience to my research topic. It felt very much as if I had found my kind of people among the international PhD students and academics at IIASA. Freed from the distractions of teaching, I was also able to focus 100% on my research and I conducted the largest-ever analysis of drought and child malnutrition.

© Matt Cooper

Now, I am very grateful to have another summer at IIASA coming up, thanks to the Peccei Award. I will again focus on the impact climate shocks like drought have on child health. however, I will build on last year’s research by looking at future scenarios of climate change and economic development. Will greater prosperity offset the impacts of severe droughts and flooding on children in developing countries? Or does climate change pose a hazard that will offset the global health gains of the past few decades? These are the questions that I hope to answer during the coming summer, where my research will benefit from many of the future scenarios already developed at IIASA.

I can’t think of a better research institute to conduct this kind of systemic, global research than IIASA, and I can’t picture a more enjoyable place to live for a summer than Vienna.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.