Nov 2, 2018 | Citizen Science, Ecosystems, Environment, Food

by Rastislav Skalsky, Ecosystems Services and Management Program, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Clay soil

As growers, we know soil is important. It supports plants, and provides nutrients and water for them to grow. But do we all appreciate how crucial the role of soil is in continuously supplying plants with water, even when it hasn’t rained for a few days or even weeks, even without extra water being added via watering?

Soil is like a sponge. It can retain rain water and, if it is not taken up by plants, soil can store it for a long time. We can feel the water in soil as soil moisture. Try it — take and hold a lump (clod) of soil — if it is wet it will leave a spot on your palm. If it’s only moist then it will feel cold — cooler than the air around. And if the soil is dry, it will feel a little warm.

Soil moisture not only can be felt, but it can also be measured — in the lab, or directly in the field with professional or low-cost soil moisture sensors.

Soil moisture in general indicates how much water is contained by the soil. But it is not always the case that soil which feels moist or wet is able to support plants. It could happen that, despite feeling moist, the soil simply does not hold enough water, or holds the water too tightly for the plants to extract it. Or the opposite, soil can sometimes contain too much water. To understand how this works, one has to learn more about how water is stored in the soil.

Water is bound to soil by physical forces. Some forces are too weak to hold water in the plant root zone and water percolates to deeper layers, where plants can no longer reach it. Other forces can be too strong, preventing water from being retrieved by the roots.

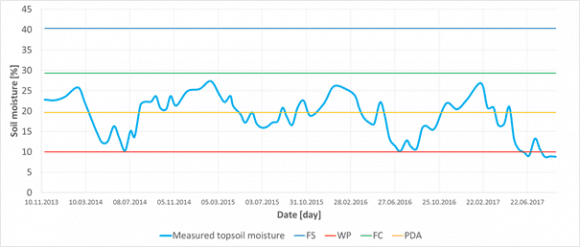

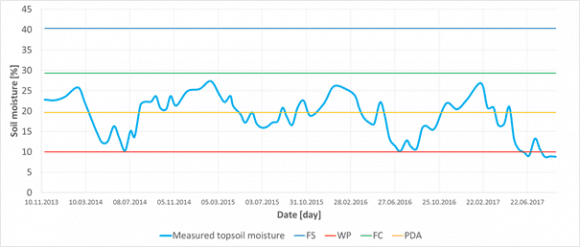

Figure 1

If soil moisture is measured at one place over time, it can reveal its seasonal dynamics. Having estimated important soil water content thresholds (FS — full saturation, FC — field capacity, PDA — point of decreased availability, and WP — wilting point) for that particular site, e.g. based on soil texture test or measurement, one can easily interpret if the measured soil moisture and say if there was enough water or not to fully support plants with water and air. In this particular case of sandy 0–30 cm deep topsoil from Slovakia, it was never wet enough to cause oxygen stress for plants, — in fact it never reached state of all capillary voids filled with water (FC). On the other hand, each summer the topsoil moisture dropped below the point of decreased availability (PDA), even got close to the wilting point or went through (WP), which means that during those periods plants suffered drought conditions.

Thresholds

In order to describe this behavior in more useful terms, plant ecologists and soil hydrologists came up with couple of important soil water content thresholds (Figure 1). These thresholds, also called “soil moisture ecological intervals”, define how easily plants can get the water out of the soil.

We speak about full saturation of soil when all empty spaces (pores/voids) are completely filled with water. Full saturation of the soil with water prevents air entering into the soil. Yet there is no force holding water in the soil. Roots need air as well as water so, if this situation continues, it eventually causes oxygen stress for most of the common plants because roots simply cannot breathe.

Soil also has different types of pores. Larger ones, which are called “gravitational pores”, are filled with water only when the soil is saturated and otherwise drains freely, and smaller ones called “capillary pores” which are small enough in size to prevent water from percolating down the soil profile by gravitation. These smaller pores can hold water even in well-drained soils and make it available for plants to extract. There are also even smaller pores where the water is held so tightly that plants cannot extract it.

Sandy soil

When all gravitational pores/voids are empty of water and it is present only in so called capillary pores/void we speak about the field water capacity — which is considered to be the best soil moisture status of the soil — enabling plants to retrieve the water they need, whilst leaving enough air for roots to breathe. If no new water is added into the soil, the soil dries as water is used by plants or evaporates. As soil dries less water is available to plants until the point of decreased availability when water remains only in the smallest capillary pores/voids. But this water is bound to soil particles so strongly that most plants are not able to extract it suffer from drought. Ultimately, all the available water is used up by plants, and the remaining water is inaccessible. Soil reaches the so-called wilting point and water is not available for the plants anymore. Plants permanently wilt and eventually die.

How Soil Characteristics Relate to Moisture

The tricky thing with soil moisture however is that the same amount of water (volumetric percent of the total soil column volume) can, in different soils, represent different amount of water available for plants. How big this difference could be is defined by many soil characteristics.

Loamy soil

The most important is the soil texture — a blend of all fine-earth soil mineral constituents (sand, silt, clay) and stones in various rates. In general, the finer the texture is (i.e. more clay, less sand) the more water is bound in the soil too tightly to be retrieved by plants. Even if the soil feels moist, plants can permanently wilt in clay soils. In contrast, those soils with coarse texture (i.e. more sand, less clay) can support plants with nearly all the water they can hold. Although the soil looks dry, plants can still effectively take the water out of it. The drawback here is that in coarse textured, sandy, soil nearly all water drains down the gravitational pores and therefore such a soil cannot support plants for very long time. That is also why medium textured soils (loam, silty loam, clay loam) are considered best for holding and providing the water for plants. Medium textured soils can effectively drain excess water, yet hold much water in capillary pores/voids for a long time, and still, only a relatively small amount of water remains unavailable for the plants.

A practical implication of this behavior of soil with different soil texture could be that one has to apply slightly different strategies to maintain soil moisture in the way that it can effectively supply plants with water. Sandy soils will require more frequent watering with smaller amount of water. It would not make any practical sense to try build-up a storage of water in these soils. All extra water added will simply drain out of the topsoil. Clay rich soils can absorb big amounts of water but a lot is bounded too strongly to the soil particles and thus not available for the plants. Therefore one should water even if the soil looks moist or wet — and if dry a lot of water must be added to recharge the topsoil so that it can support plants effectively. With loamy soils it is possible to be more relaxed with watering frequency, simply because one can build solid storage of water in such soils. Adding a bit more water than is necessary is perfectly fine with these soils because the water is effectively kept in the soil profile and it can be used later on.

Interested in learning more? Why not sign up for GROW Observatory’s next free online course – Citizen Research: From Data to Action – to discover how citizen-generated data on soils, food and a changing climate can create positive change in the world. Starts 5th November.

This blog was originally published on https://medium.com/grow-observatory-blog/moisture-matters-a9e33dc880a1

Mar 21, 2018 | Citizen Science, Environment

By Linda See and Inian Moorthy, Ecosystems Services and Management Program

A recent estimate indicates that there are around 3 trillion trees on the Earth’s surface, of which around 15 billion are cut down each year [1]. When we think of these vast numbers, we usually picture Amazonian rainforests or landscapes of evergreen trees surrounded by lakes and mountains. We rarely think of urban trees and the important role they play in making cities a healthier, greener place to live.

©Durch pecaphoto77 | Shutterstock

Raising awareness of the importance of urban forests for quality of life is part of the theme of this year’s United Nations International Day of Forests. At IIASA we are actively contributing to this awareness through an EU-funded project called LandSense. The aim of the project is to create a citizen-powered observatory for environmental monitoring of landscapes, particularly those that are changing and affecting citizen wellbeing, livelihoods, and biodiversity. Monitoring trees, and more specifically urban greenspaces, is a fundamental component of the LandSense project. Trees can reduce air pollution in cities by absorbing and filtering out the gases and particles that cause harm. Additionally, trees have a cooling effect on cities, which is increasingly important as temperatures rise due to climate change. In cities, the urban heat island effect results in higher temperatures during heat waves, often leading to health problems and even fatalities. Monitoring the presence of urban trees and fostering citizen access to urban greenspaces should therefore not be underestimated in terms of their contribution to promoting urban health, wellbeing, and sustainable cities.

With this urban focus in mind, the LandSense citizen observatory is engaging citizens in Vienna and Amsterdam in monitoring their local greenspaces, and in this way obtaining their perceptions about the quality and extent of these areas. A smart phone app developed at IIASA, guides participating citizens to specific locations in the city and asks them a series of questions, some of which relate to the quality of the trees in their area. This feedback can help city authorities to better understand the views of their citizens. The ultimate goal is to create dynamic and temporal maps of greenspace quality across the city, which can guide timely local decision making. The LandSense app will for example, directly contribute to STEP 2025, the urban development plan for Vienna.

This participatory approach not only gives citizens a better understanding of changing greenspaces in the city, but also empowers them to elicit action from city authorities in terms of improving poorly perceived greenspaces. By participating in this process, citizens are actively engaging in dialogue with the city authorities – getting their voices heard and influencing where future improvements will take place. Ultimately, by improving greenspaces and urban forests, citizens are helping to increase the wellbeing and quality of life of urban dwellers in the city.

We are currently testing the mobile app with students in Vienna and Amsterdam before launching broader citizen-based greenspace monitoring campaigns in the future. If you want to find out more, please visit the LandSense website for details or follow us on Twitter @LandSense.

References

[1] Crowther TW, Glick HB, Covey KR, et al (2015). Mapping tree density at a global scale. Nature 525:201–205. doi: 10.1038/nature14967

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 19, 2017 | Citizen Science, Food, Sustainable Development

By Myroslava Lesiv, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program.

The public can contribute considerably to science by filling the gaps of missing information in many research areas, for example, monitoring land use, biodiversity, or forest degradation. Crowdsourcing campaigns organized by research institutions bring together citizens interested in science and help solving research questions to the benefit of the whole world.

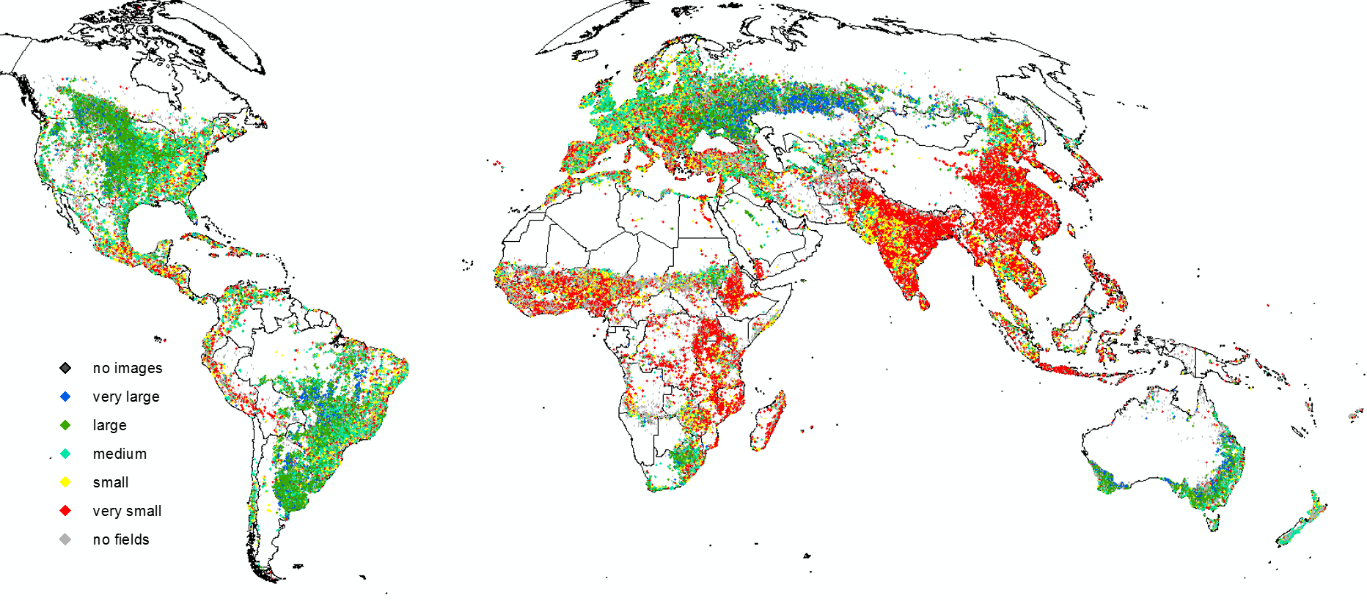

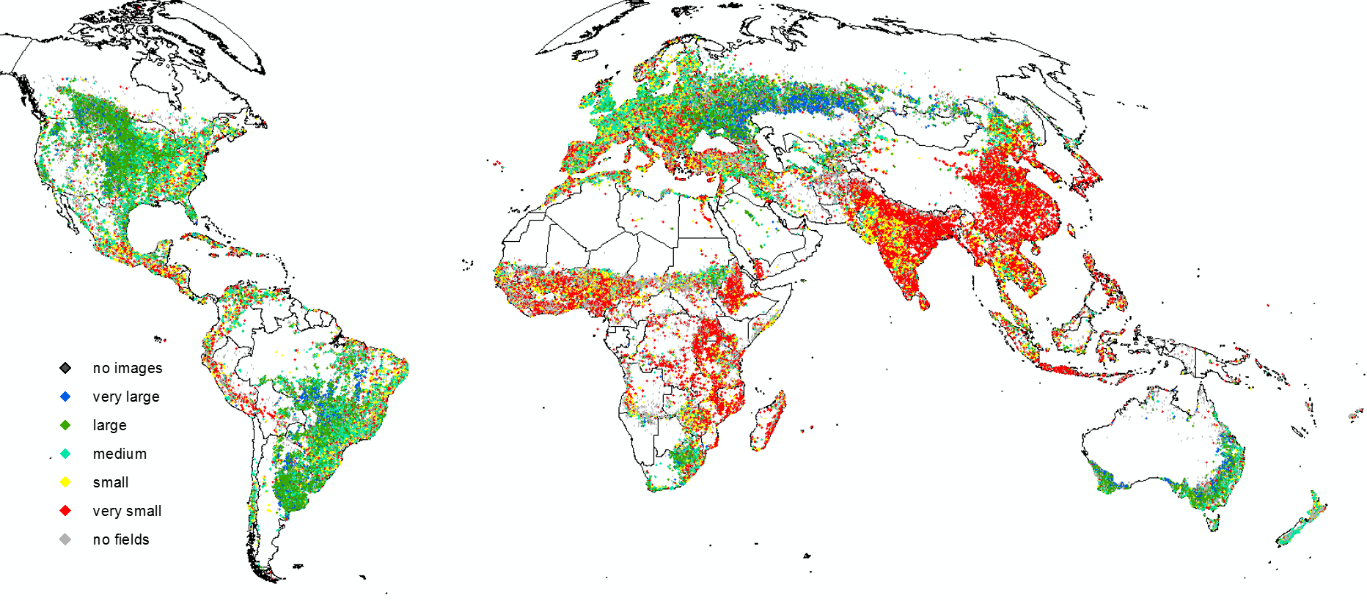

This June, the IIASA Geo-Wiki team ran the Global Field Size campaign, encouraging citizen scientists to classify field sizes on satellite images. Its aim was to develop a global field sizes dataset, which will be used as input to create an improved global cropland field size map for agricultural monitoring and food security assessments. The field sizes dataset can also help us determine what types of satellite data are needed for agricultural monitoring in different parts of the world.

Geo-Wiki interface for collecting field size data. Background layer: Google Maps.

Why are field sizes so important? They provide us with valuable information to tackle challenges of food security. A recent study showed that more than a half the food calories produced globally comes from smallholder farmers, who often make up the most vulnerable parts of population, living in poverty. Within this scope, the field size dataset fills the gaps of missing information, especially for countries that have a limited food supply and lack a well-developed agricultural monitoring system.

The Global Field Size campaign has been one of the most successful crowdsourcing campaigns run through the Geo-Wiki engagement platform. Within one month, 130 participants completed 390,000 tasks – that is, they classified the field sizes in 130,000 locations around the globe!

So we can see that crowdsourcing is powerful, but can we trust the data? Is it accurate enough to be used in different applications? I think it is! The Geo-Wiki team has significant experience in running crowdsourcing campaigns; one of the key lessons we have learned from previous Geo-Wiki campaigns is the importance of training the public to increase the quality of the crowdsourced data.

This campaign was designed so that the participants learned over time how to delineate fields in different regions of the world, and, at the same time, pay special attention to the quality of their submissions. At the end of the campaign, the majority of participants gave us a feedback that, to them, this campaign was indeed a learning exercise. From our end, I have to add, this was also a challenging campaign, as fields are so diverse in shape, continuity of coverage, crop type, irrigation, etc.

Global distribution of dominant field sizes. Cartography by Myroslava Lesiv. Country boundaries: GAUL. Software: ArcMap 10.1.

During the campaign, the crowd was asked to identify whether there were fields in a certain location, and determine the relevant field sizes by the visual interpretation of very high-resolution Google and Bing imagery. A “field” was defined as an agricultural area that included annual or perennial croplands, fallow, shifting cultivation, pastures or hayfields. The collected data can also be used to identify areas falsely mapped as cropland.

Now the team is focused on summarizing the results of the campaign, processing the collected field size data, and preparing them for scientific publication. We will ensure that the published dataset is of high quality and can be used by others with confidence!

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 30, 2017 | Environment, Food & Water, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

Two things are distinctly noticeable when you meet Cornelius Hirsch—a cheerful smile that rarely leaves his face and the spark in his eyes as he talks about issues close to his heart. The range is quite broad though—from politics and economics to electronic music.

Cornelius Hirsch

After finishing high school, Hirsch decided to travel and explore the world. This paid off quite well. It was during his travels, encompassing Hong Kong, New Zealand, and California, that Hirsch started taking a keen interest in economic and political systems. This sparked his curiosity and helped him decide that he wanted to take up economics for higher studies. Therefore, after completing his masters in agricultural economics, Hirsch applied for a position as a research associate at the Austrian Institute of Economic Research and enrolled in the PhD-program of the Vienna University of Economics and Business to study trade, globalization, and its impact on rural areas. Currently, he is looking at subsidies and tariffs for farmers and the agricultural sector at a global scale.

As part of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program at IIASA, Hirsch is digging a little deeper to analyze how foreign direct investments (FDI) in agricultural land operate. “Since 2000, the number of foreign land acquisitions have been growing—governmental or private players buy a lot of land in different countries to produce crops. I was interested in knowing why there are so many of these hotspots in the world— sub-Saharan Africa, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia—why are people investing in these areas?,” says Hirsch.

Farming in one of the large agricultural areas in Indonesia ©CIFOR I Flickr

Increased food demand from a growing world population is leading to an increased rate of investment in agriculture in regions with large stretches of fertile land. That these regions are largely rain-fed make them even more attractive for investors as they save the cost of expensive irrigation services. In fact, Hirsch argues that “the term land-grabbing is misleading. It should actually be water-grabbing as water is the foremost deciding factor—even more important than simply land abundance.”

Some researchers have found an interesting contrast between FDI in traditional sectors, such as manufacturing, and the ones in agricultural land. While investors in the former look for stable institutions and good governmental efficiency, FDI in land deals seems to target regions with less stable institutions. This positive relationship between corruption and FDI is completely counterintuitive. Hirsch says that one reason could be that “sometimes weaker institutions are easier to get through when it comes to such vast amount of lands. A lot of times these deals and contracts are oral and have no written proof—the contracts are not transparent anyway.”

For example in South Sudan, the land and soil conditions seem to be so good that investors aren’t deterred despite conflicts due to corrupt practices or inefficient government agencies.

One of the indigenous communities in Madagascar, a place which is vulnerable to land acquisitions © IamNotUnique I Flickr

One area that often goes unnoticed is the violation of land rights of indigenous communities. If a government body decides to sell land or give out production licenses to investors for leasing the land without consulting the actual community, it is only much later that the affected community finds out that their land has been given away. Left with no land and hence no source of livelihood, these communities are forced to migrate to urban areas.

A strain of concern enters his voice as Hirsch talks about the impact. “Land as big as two times the area of Ecuador has been sold off in the past—but it accounts for a tiny percentage of the global production area.” With rising incomes and greater consumption of meat, a lot of land is used to produce animal feed crops. “This is a very inefficient way of using land,” he says.

During the summer program at IIASA, Hirsch is generating data that will help him look at these deals in detail and analyze the main factors that are taken into consideration before finalizing a land deal. At the moment he is only able to give an overview of land-grabbing at the global level. With more data on the location of the deals he can look at the factors that influence these decisions in the first place such as the proximity between the two countries involved in agricultural investments and the size of their economies.

While there is always huge media coverage when a scandal about these land acquisitions comes out in the open, Hirsch seems determined to dig deeper and uncover the dynamics involved.

About the researcher

Cornelius Hirsch is a research associate at the Austrian Institute of Economics and Research (WIFO). At IIASA he is working under the supervision of Tamas Krisztin and Linda See in the Ecosystems Services and Management Program (ESM).

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 26, 2017 | Alumni, Climate Change, Poverty & Equity, Sustainable Development, Water, Young Scientists

Adil Najam is the inaugural dean of the Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University and former vice chancellor of Lahore University of Management Sciences, Pakistan. He talks to Science Communication Fellow Parul Tewari about his time as a participant of the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) and the global challenge of adaptation to climate change.

How has your experience as a YSSP fellow at IIASA impacted your career?

The most important thing my YSSP experience gave me was a real and deep appreciation for interdisciplinarity. The realization that the great challenges of our time lie at the intersection of multiple disciplines. And without a real respect for multiple disciplines we will simply not be able to act effectively on them.

Prof. Adil Najam speaking at the Deutsche Welle Building in Bonn, Germany in 2010 © Erich Habich I en.wikipedia

Recently at the 40th anniversary of the YSSP program you spoke about ‘The age of adaptation’. Globally there is still a lot more focus on mitigation. Why is this?

Living in the “Age of Adaption” does not mean that mitigation is no longer important. It is as, and more, important than ever. But now, we also have to contend with adaptation. Adaptation, after all, is the failure of mitigation. We got to the age of adaptation because we failed to mitigate enough or in time. The less we mitigate now and in the future, the more we will have to adapt, possibly at levels where adaptation may no longer even be possible. Adaption is nearly always more difficult than mitigation; and will ultimately be far more expensive. And at some level it could become impossible.

How do you think can adaptation be brought into the mainstream in environmental/climate change discourse?

Climate discussions are primarily held in the language of carbon. However, adaptation requires us to think outside “carbon management.” The “currency” of adaptation is multivaried: its disease, its poverty, its food, its ecosystems, and maybe most importantly, its water. In fact, I have argued that water is to adaptation, what carbon is to mitigation.

To honestly think about adaptation we will have to confront the fact that adaptation is fundamentally about development. This is unfamiliar—and sometimes uncomfortable—territory for many climate analysts. I do not believe that there is any way that we can honestly deal with the issue of climate adaptation without putting development, especially including issues of climate justice, squarely at the center of the climate debate.

COP 22 (Conference of Parties) was termed as the “COP of Action” where “financing” was one of the critical aspects of both mitigation and adaptation. However, there has not been much progress. Why is this?

Unfortunately, the climate negotiation exercise has become routine. While there are occasional moments of excitement, such as at Paris, the general negotiation process has become entirely predictable, even boring. We come together every year to repeat the same arguments to the same people and then arrive at the same conclusions. We make the same promises each year, knowing that we have little or no intention of keeping them. Maybe I am being too cynical. But I am convinced that if there is to be any ‘action,’ it will come from outside the COPs. From citizen action. From business innovation. From municipalities. And most importantly from future generations who are now condemned to live with the consequences of our decision not to act in time.

© Piyaset I Shutterstock

What is your greatest fear for our planet, in the near future, if we remain as indecisive in the climate negotiations as we are today?

My biggest fear is that we will—or maybe already have—become parochial in our approach to this global challenge. That by choosing not to act in time or at the scale needed, we have condemned some of the poorest communities in the world—the already marginalized and vulnerable—to pay for the sins of our climatic excess. The fear used to be that those who have contributed the least to the problem will end up facing the worst climatic impacts. That, unfortunately, is now the reality.

What message would you like to give to the current generation of YSSPers?

Be bold in the questions you ask and the answers you seek. Never allow yourself—or anyone else—to rein in your intellectual ambition. Now is the time to think big. Because the challenges we face are gigantic.

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.