Jun 21, 2017 | Data and Methods

By Luke Kirwan, IIASA open access manager

At this year’s European Geosciences Union a panel of experts convened to debate the benefits of open science. Open science means making as much of the scientific output and processes publicly visible and accessible, including publications, models, and data sets.

Open science includes not just open access to research findings, but the idea of sharing data, methods, and processes. ©PongMoji | Shutterstock

In terms of the benefits of open science the panelists—who included representatives from academia, government, and academic publishing—generally agreed that openness favors increased collaboration and the development of large networks, especially in terms of geoscience data, which improves precision in the interpretation of results. There is evidence that sharing data and linking to publications increases both readership and citations. A growing number of funding bodies and journals are also requiring researchers to make the data underlining a publication as publicly available as possible. In the context of Horizon 2020, researchers are instructed to make their data ‘as open as possible, as closed as necessary.’

This statement was intentionally left vague, because the European Research Council (ERC) realized that a one size fits all approach would not be able to cover the entirety of research practices across the scientific community, said Jean-Paul Bourguignon, president of the ERC.

Barbara Romanowicz from Collège de France and Institut de Physique du Glove de Paris also pointed to the need for disciplines to develop standardized metadata standards and a community ethic to facilitate interoperability. She also pointed out that the requirements for making raw data openly accessible are quite different to those for making models accessible. These problems require increased resources to be adequately addressed.

Roche DG, Lanfear R, Binning SA, Haff TM, Schwanz LE, Cain KE, Kokko H, Jennions MD, Kruuk LEB (2014). Troubleshooting public data archiving: suggestions to increase participation. PLOS Biology. 12 (1): e1001779. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001779.

Playing devil’s advocate, Helen Glaves from the British Geological Survey pointed to several areas of potential concern. She questioned whether the costs involved in providing long-term preservation and access to data are the most efficient use of taxpayers money. She also suggested that charging for access could be used to generate revenues to fund future research. However, possibly a more salient concern for researchers that she raised was the fear of scientists that making their data and research available in good faith, could allow their hard work to be passed off by another researcher as their own.

Many of these issues were raised by audience members during the questions and answer session. Scientists pointed out that research data involved a lot of hard work to collate, they had concerns about inappropriate secondary reuse, jobs and research grants are highly competitive. However, the view was also expressed that paying for access to research fundamentally amounts to ‘double taxation’ if the research has been funded by public money, and that even restrictive sharing is better than not sharing at all. It was also argued that incentivising sharing through increased citations and visibility would both help encourage researchers to make their research more open and aide researchers in the pursuit of grants or research positions. To bring about these changes in research practices will involve investing in training the next generation of scientists in these new processes.

Here at IIASA we are fully committed to open access and in the library, we assist our researchers with any queries or issues they may have with widely sharing their research. As well as improving the visibility of research publications through Pure, our institutional repository, we can also assist with making research data discoverable and citable.

A video of the discussion is available on YouTube.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jun 12, 2017 | Citizen Science

By Linda See, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Satellites have changed the way that we see the world. For more than 40 years, we have had regular images of the Earth’s surface, which have allowed us to monitor deforestation, visualize dramatic changes in urbanization, and comprehensively map the Earth’s surface. Without satellites, our understanding of the impacts that humans are having on the terrestrial ecosystem would be much diminished.

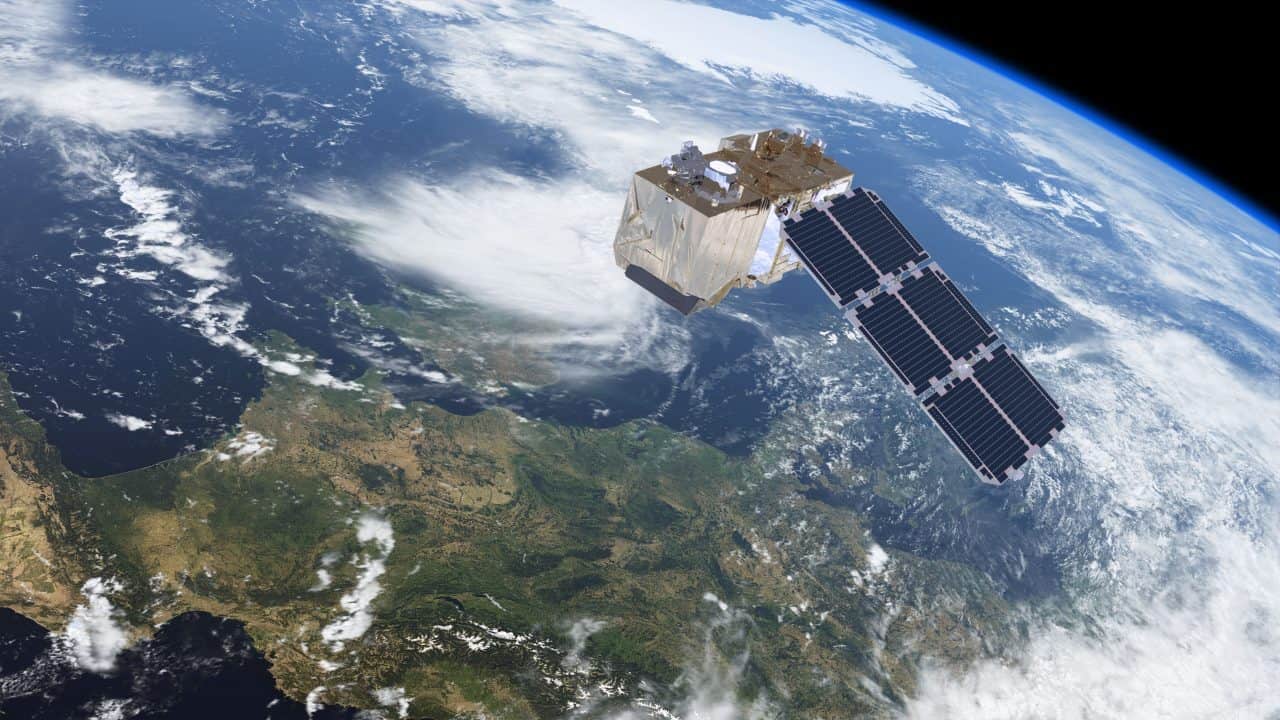

The Sentinel-2 satellite provides high-resolution land-cover data. © ESA/ATG medialab

Over the past decade, many more satellites have been launched, with improvements in how much detail we can see and the frequency at which locations are revisited. This means that we can monitor changes in the landscape more effectively, particularly in areas where optical imagery is used and cloud cover is frequent. Yet perhaps even more important than these technological innovations, one of the most pivotal changes in satellite remote sensing was when NASA opened up free access to Landsat imagery in 2008. As a result, there has been a rapid uptake in the use of the data, and researchers and organizations have produced many new global products based on these data, such as Matt Hansen’s forest cover maps, JRC’s water and global human settlement layers, and global land cover maps (FROM-GLC and GlobeLand30) produced by different groups in China.

Complementing Landsat, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Sentinel-2 satellites provide even higher spatial and temporal resolution, and once fully operational, coverage of the Earth will be provided every five days. Like NASA, ESA has also made the data freely available. However, the volume of data is much higher, on the order of 1.6 terabytes per day. These data volumes, as well as the need to pre-process the imagery, can pose real problems to new users. Pre-processing can also lead to incredible duplication of effort if done independently by many different organizations around the world. For example, I attended a recent World Cover conference hosted by ESA, and there were many impressive presentations of new applications and products that use these openly available data streams. But most had one thing in common: they all downloaded and processed the imagery before it was used. For large map producers, control over the pre-processing of the imagery might be desirable, but this is a daunting task for novice users wanting to really exploit the data.

In order to remove these barriers, we need new ways of providing access to the data that don’t involve downloading and pre-processing every new data point. In some respects this could be similar to the way in which Google and Bing provide access to very high-resolution satellite imagery in a seamless way. But it’s not just about visualization, or Google and Bing would be sufficient for most user needs. Instead it’s about being able to use the underlying spectral information to create derived products on the fly. The Google Earth Engine might provide some of these capabilities, but the learning curve is pretty steep and some programming knowledge is required.

Instead, what we need is an even simpler system like that produced by Sinergise in Slovenia. In collaboration with Amazon Web Services, the Sentinel Hub provides access to all Sentinel-2 data in one place, with many different ways to view the imagery, including derived products such as vegetation status or on-the-fly creation of user-defined indices. Such a system opens up new possibilities for environmental monitoring without the need to have either remote sensing expertise, programming ability, or in-house processing power. An exemplary web application using Sentinel Hub services, the Sentinel Playground, allows users to browse the full global multi-spectral Sentinel-2 archive in matter of seconds.

This is why we have chosen Sentinel Hub to provide data for our LandSense Citizen Observatory, an initiative to harness remote sensing data for land cover monitoring by citizens. We will access a range of services from vegetation monitoring through to land cover change detection and place the power of remote sensing within the grasp of the crowd.

Without these types of innovations, exploitation of the huge volumes of satellite data from Sentinel-2, and other newly emerging sources of satellite data, will remain within the domain of a small group of experts, creating a barrier that restricts many potential applications of the data. Instead we must encourage developments like Sentinel Hub to ensure that satellite remote sensing becomes truly usable by the masses in ways that benefits everyone.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 29, 2016 | Risk and resilience

By Nadejda Komendantova, IIASA Risk and Resilience Program

A transition to new energy sources—whether renewable, nuclear, or shale—does not just depend on technical availability and economic feasibility. In order for new projects to succeed, human factors, such as public and social acceptance, and willingness to use technology or to pay for it, are essential but often overlooked. It is important to understand these factors, because differences in views and perceptions of technology risks, benefits, and costs might lead to conflicts that could threaten the success of new projects.

Conflicts often appear between two or more parties with incompatible goals, different interests, or different risk perceptions, which can develop into either cooperation or conflict. For example, public opposition can lead to cancellation or delay of a planned project, and differences in views and risk perceptions can result in conflicts among different stakeholder groups. At the same time, if policymakers take into account this heterogeneity of views, the knowledge on the ground can lead to a better implementation of energy projects with more benefits for society and a smaller impact on the environment and hosting communities.

Row of high voltage pylons in the desert of Wadi Rum, Jordan ©Pierre Brumder | Adobe Stock Photo

An energy transition is currently taking place in the Middle East and North Africa. The region faces a number of challenges such as rising energy demand, unstable energy imports, increasing pressure on environmental resources, expectations of socioeconomic development, and political transformation. Morocco, Jordan, Tunisia, and other countries in the region are discussing new electricity infrastructure. Although large-scale deployment of renewable energy sources receives political support in this discussion, fossil fuels, and new emerging technologies such as shale oil and nuclear power are two prominent alternatives in the countries’ national development plans.

For this energy transition to succeed, policymakers in the region must adopt an adaptive and inclusive governance approach, which addresses possible risks, benefits, challenges, and socio-ecological shifts. In order to find compromise solutions, this approach should be based on an understanding of the positions of each stakeholder group involved in the project planning and affected by its implementation.

To understand these potential conflicts, a group of IIASA Risk and Resilience Program researchers, including myself, Jenan Irshaid, Love Ekenberg and Joanne Bayer, are conducting a series of six stakeholder workshops in Jordan. Each of the workshops targets different stakeholder groups such as local communities, NGOs, financial institutions, project developers, private companies, academia, young leaders, and national policymakers, including ministries of public works, of water and irrigation, energy and mineral resources, and municipal affairs. The goal of these workshops is to understand how different groups of stakeholders see risks and benefits of different electricity generation technologies, including renewables, fossil fuels, and nuclear, as well as views and visions of different stakeholders of Jordan in 2040 in terms of the social, environmental, and economic situation.

In our research we go beyond the existing discussion on social acceptance as a proxy of a Not-in-My-Back-Yard (NIMBY) attitude. NIMBY is often a misleading concept to understand local objections, because it is frequently understood as some kind of “social gap” between the need of policy intervention, settled at the national level, and the hostility towards its deployment at the local level. The NIMBY concept often includes skepticism of different stakeholder groups towards positions of the others. Also the term “acceptance” towards technology or infrastructure innovation often means a passive position towards something that cannot be changed. In contrary, willingness to use technology or to participate financially means a more active position.

In recent research, we discuss the usefulness of a model that we call “decide-announce-defend” (DAD), and try to understand how integration of various views and risk perceptions can lead to enhanced legitimacy of decision-making processes and trust. To understand the trade-offs between benefits of national energy goals and conflict sensitivity, we evaluated each electricity generation technology that could be relevant for Jordan against a set of criteria, including domestic value chain integration, use of domestic resources, technology and knowledge transfer, global warming potential, electricity system costs, job creation processes, pressure on land and water resources as well as safety, air pollution and non-emission waste.

Participants in the workshop. ©Nadejda Komendantova | IIASA

The workshops are organized in collaboration with the University of Jordan as part of the Middle East North African Sustainable Electricity Trajectories (MENA Select) project, which is supported by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and involves following partners: Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC), University of Flensburg, Germanwatch, Wuppertal Institute and IIASA as well as a number of partners in the MENA region, such as MENARES, University of Jordan, and DUN.

Further information

Ekenberg, L., Hansson, K., Danielson, M., Cars, G., (2017) Deliberation, Representation and Equity: Research Approaches, Tools and Algorithms for Participatory Processes, Open Book Publishers, 2017.

Komendantova, N., and Battaglini, A., (2016). Beyond Decide-Announce-Defend (DAD) and Not-in-My-Backyard (NIMBY) models? Addressing the social and public acceptance of electric transmission lines in Germany. Energy Research and Social Science, 22. Pp.224-231.

Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Scolobig, A., Ferlisi, S., Cascini, L. and Thompson, M. (2016) Expert engagement in participatory processes: translating stakeholder discourses into policy options. Natural Hazards, 81 (S1). pp. 69-88. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/view/iiasa/182.html

Yazdanpanah, M., Komendantova, N., Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Shirazi, Z., (2015). “Green or In Between? Examining Young Adults’ Perceptions of Renewable Energy in Iran”. Energy Research and Social Science 8 (2015), 78-85

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 10, 2016 | Alumni, Demography, Young Scientists

by Julia M. Puaschunder, alumna of the IIASA Young Scientist Summer Program 2016.

The world is on the move. Currently, more than 250 million people live outside their countries of birth. Of the moving masses, an estimated 6% are refugees fleeing across borders to more favorable environments. The ongoing European refugee crisis has increased the pressure to reap the benefits from migration while alleviating the burdens of societal movement.

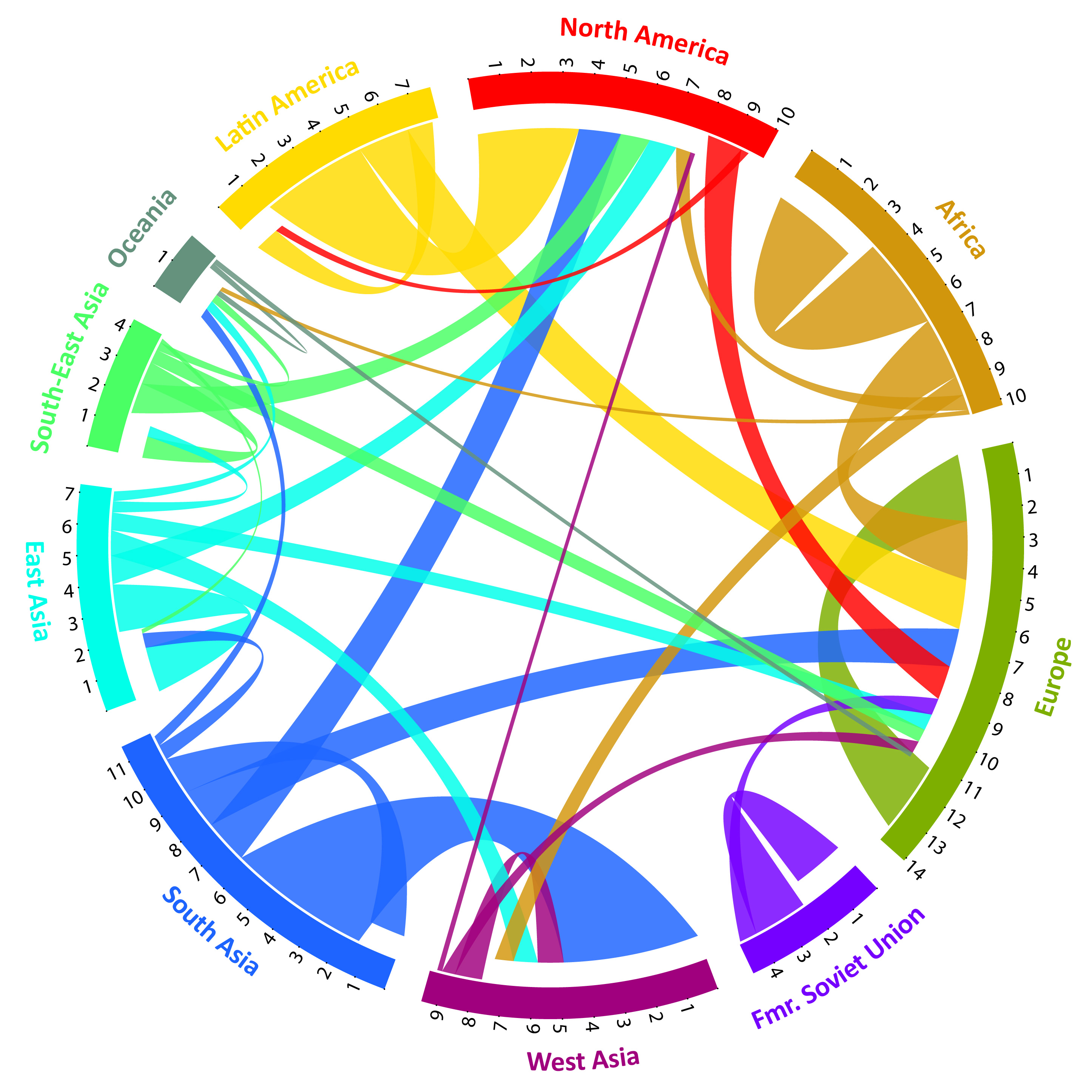

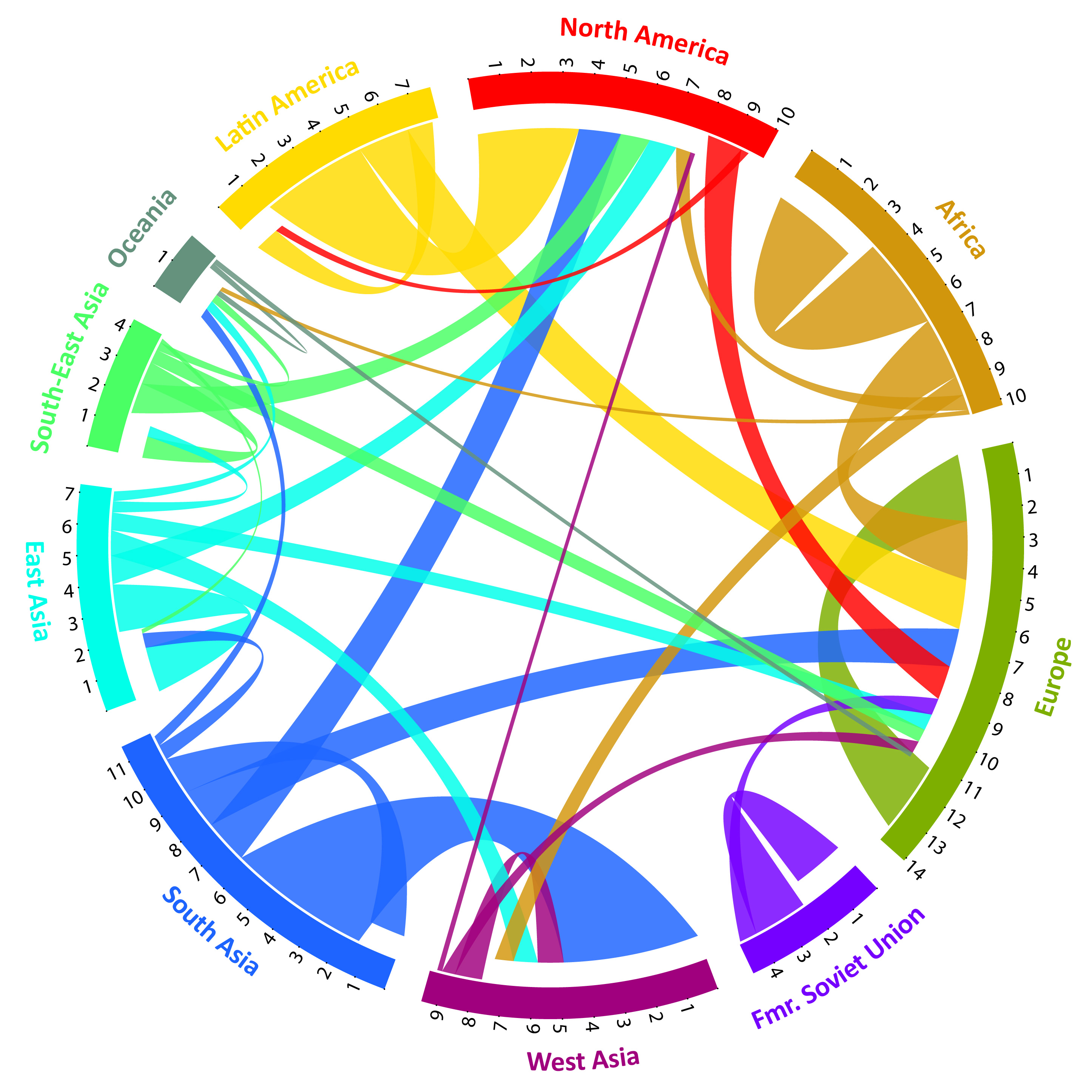

Estimates of directional flows between 123 countries between 2005-2010. Only flows containing at least 50,000 migrants are shown. “The Global Flow of People” (www.global-migration.info) is by Nikola Sander, Guy Abel & Ramon Bauer, and published in Science as “Quantifying global international migration flows” in 2014 (vol. 343: 1520-152).

Concerns were recently raised as to whether granting asylum to refugees—who often make up the most productive parts of their original populations—prevents (re)development in their fractionated home countries? An important consideration absent in these debates are the monetary gifts migrants send to their family members back home.

The World Bank estimates that migrants currently return around 450 billion US Dollars per year to the developing countries they came from, and this number is expected to rise. These monetary remittances have multiple positive impacts, including economic growth. As refugees are primarily younger to middle-aged, their remittances likely pay for their wives and children’s access to medical care and education, or support their parents when pension systems are missing.

Intergenerational monetary transfers are therefore the focus of my recent publication Gifts Without Borders. Contrary to conventional institutionalized sustainable development, remittances grounded in intergenerational care benefit from communication within families. Long-lasting family ties allow direct feedback. People truly care about their loved ones back home and families share their day-to-day experiences honestly. Intergenerational remittances beyond borders are thus a purer and potentially longer-enduring pathway to sustainable development, as these stable funding streams’ impact is more accountable than standard international aid.

Based on World Bank and OECD data covering almost all countries of the world, my forthcoming publication in the book ‘Intergenerational Responsibility in the 21st Century’ highlights that the intergenerational glue of a migrating population helps countries lacking socially responsible and future-oriented public sectors. Rather than blaming asylum-granting countries for removing the labor force from fragile territories, hosting refugees is portrayed as making use of human capital in stable economies, while refugees—at the same time—develop their former homelands by direct monetary contributions in a natural, transparent, and accountable way. In the age of migration, analyzing intergenerational networks and their financial flows is an important, but unexplored, facet of sustainable development. My findings open prospective research avenues on how we can align the economic outcomes of human capital mobility with sustainable development.

The IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program granted a vibrant setting to discuss my findings in a group of international, diverse, and multi-disciplinary future academic leaders during this summer, which was filled with beautiful moments in the historic Schloss Laxenburg in Austria. Recently IIASA also launched a Joint Research Centre of Expertise with the European Commission on Population and Migration, which aims to predict how migration will impact future economies and societies. In addition, the Advanced Systems Analysis (ASA) Program hosts the ‘Economic migration, capital flows, and welfare’ collaboration between ASA and the World Population Program to model dynamics of economic migration and investment. This research is also directly related to my New School Economic Review paper ‘Putty Capital and Clay Labor: Differing European Union Capital and Labor Freedom Speeds in Times of European Migration,’ which elucidates trade differences in capital and labor flows gravitating the benefits and burdens of globalization unequally and the potential problems arising for the European project from migration.

The Alpbach-Laxenburg Group Retreat 2016 on New Business Models for Sustainable Development. © Matthias Silveri | IIASA

Above all, attending the IIASA 2016 Alpbach-Laxenburg Group Retreat at the European Forum Alpbach helped to enhance my understanding of the relationship between migration and intergenerational responsibility. All these endeavors are targeted at contributing to sustainable development in a world on the move.

More information on the author of the post: www.juliampuaschunder.com

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jun 2, 2016 | Climate Change

By Katherine Leitzell, IIASA science writer and press officer (and cyclist)

In May over 50 IIASA staff members took part in the Austrian Bike to Work month (Osterreich Radelt zur Arbeit), logging 11,681 kilometers riding to and from the institute in Laxenburg. The institute took fifth place in Austria in terms of kilometers ridden, and first place in Lower Austria.

According to the Austrian initiative’s calculations, this effort translated into saving over 1900 kg of CO2 emissions, or on average 36 kg per person—which is approximately 4% of an average Austrian’s monthly CO2 emissions. However, this calculation assumed that each of the IIASA cyclists would have been otherwise driving alone in a car. Since many people ride the bus or take public transport if they’re not biking, the actual emission savings from our cycling efforts in May were in fact much less. In fact, since buses and trains run anyway, cycling to work may make no impact whatsoever on emissions of air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Does that mean it’s not worth it to make the effort?

The author’s route to the office. © Katherine Leitzell | IIASA

IIASA researcher Jens Borken has analyzed the impacts that our daily travel has on the individual climate footprint. Personal mobility—all kinds of travel—make up about one third of the average European’s annual greenhouse gas emissions: the rest come from consumption choices and household heating and energy use. Of the carbon footprint from mobility, he says, commuting generally only makes up 10-15% of that. The largest part of the mobility budget is related to shorter and longer distance leisure travel, and in particular from air travel.

“From a quantitative perspective, the climate benefit of riding your bike is small, but it can be one step on a path to a low-carbon lifestyle.” says Borken. “As researchers who work on climate change, riding a bike to work (and possibly further) brings one piece of our lives in line with the message that avoiding fossil fuel consumption is imperative. I think that that is valuable. But it need not stop there. Travel choices are important, especially for longer distances, but so are consumption choices and energy usage and efficiency.”

Charlie Wilson, a researcher at the Tyndall Centre and IIASA, recently won a grant from the European Research Council to explore the role that social influence plays in spreading climate innovations. He says, “As social animals we are strongly influenced by what others do; as psychological beings we strive for consistency. Changing a behavior – like cycling to work – may have a small impact in isolation. But this impact is magnified through positive spillover effects. Others may imitate or be inspired by our commitment to cycling. And this change in behavior may also strengthen the pro-environmental aspects of our own self-identity, reducing dissonance between our work and domestic lives, and supporting further changes in behavior.”

Of course there are benefits of cycling beyond the environmental or climate impact, which is one reason that once they start, many people keep it up. Cycling regularly can save money compared to commuting by car or public transport, and like any regular form of exercise, it can bring health benefits and stress relief. It also brings autonomy and flexibility compared to public transport.

Borken points to research showing that the health benefits of cycling outweigh the exposure to air pollutants that a cyclist might experience on busy city streets—and that automobile drivers are exposed to even higher levels of air pollution within their cars. Cyclists who ride to IIASA, located about 15km outside Vienna, probably have even lower exposure to air pollution riding along tree-lined bike paths.

“Riding to work in the morning wakes me up and prepares me for the day ahead. Even if windy and challenging, the return in the evening calms the mind while riding with colleagues at a pace that allows us to chat at the end of a busy workday. It’s truly one of the best ways to get exercise and stay healthy – good for the heart, good for the environment and, most importantly, good for the soul,” says Michaela Rossini, manager of the IIASA library and a co-organizer of Bike to Work Month at the institute.

For some staff members, one side benefit of cycling to IIASA is the beautiful sunrise along the Danube River ©Michaela Rossini | IIASA

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.