Feb 14, 2020 | China, Environment, Food & Water, Water, Women in Science

By Maryna Strokal, Department of Environmental Sciences, Water Systems and Global Change, Wageningen University and Research, The Netherlands

Maryna Strokal discusses a new integrated approach to finding cost-effective solutions for nutrient pollution and coastal eutrophication developed with IIASA colleagues.

© Huy Thoai | Dreamstime.com

Have you ever wondered why the water in some rivers appear to be green? The green tinge you see is due to eutrophication, which means that too many nutrients – specifically nitrogen and phosphorus – are present in the water. This happens because rivers receive these nutrients from various land-based activities like run-off from agricultural fields and sewage effluents from cities. Rivers in turn export many of these nutrients to coastal waters, where it serves as food for algae. Too many nutrients, however, cause the algae and their blooms to grow more than normal. Because algae consumes a lot of oxygen, this lowers the available oxygen supply in the water, killing off fish and other marine life. Some algae can also be toxic to people when they eat seafood that have been exposed to, or fed on it. Polluted river water on the other hand, is unfit for direct use as drinking water, or for cooking, showering, or any of our other daily needs. Before we can use this water, it needs to be treated, which of course costs money.

To better understand and address these issues, I worked with colleagues from IIASA, Wageningen University, and China to develop an integrated approach to identify cost-effective solutions (read cheapest) to reduce river pollution and thus coastal eutrophication. Our integrated approach takes into account human activities on land, land use, the economy, the climate, and hydrology. We implemented the new approach for the Yangtze Basin in China.

The Yangtze is the third longest river in the world and exports nutrients from ten sub-basins to the East China Sea, where the coast often experiences severe eutrophication problems that may increase in the coming years. The Chinese government has called for effective actions to ensure clean water for both people and nature.

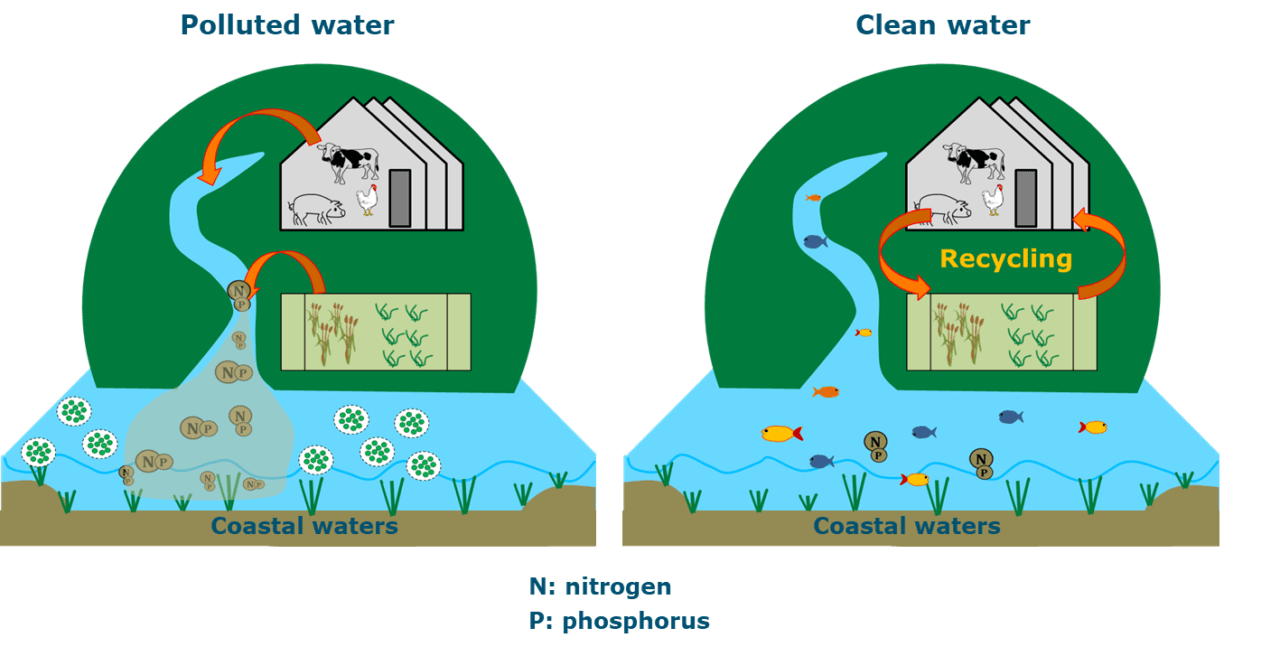

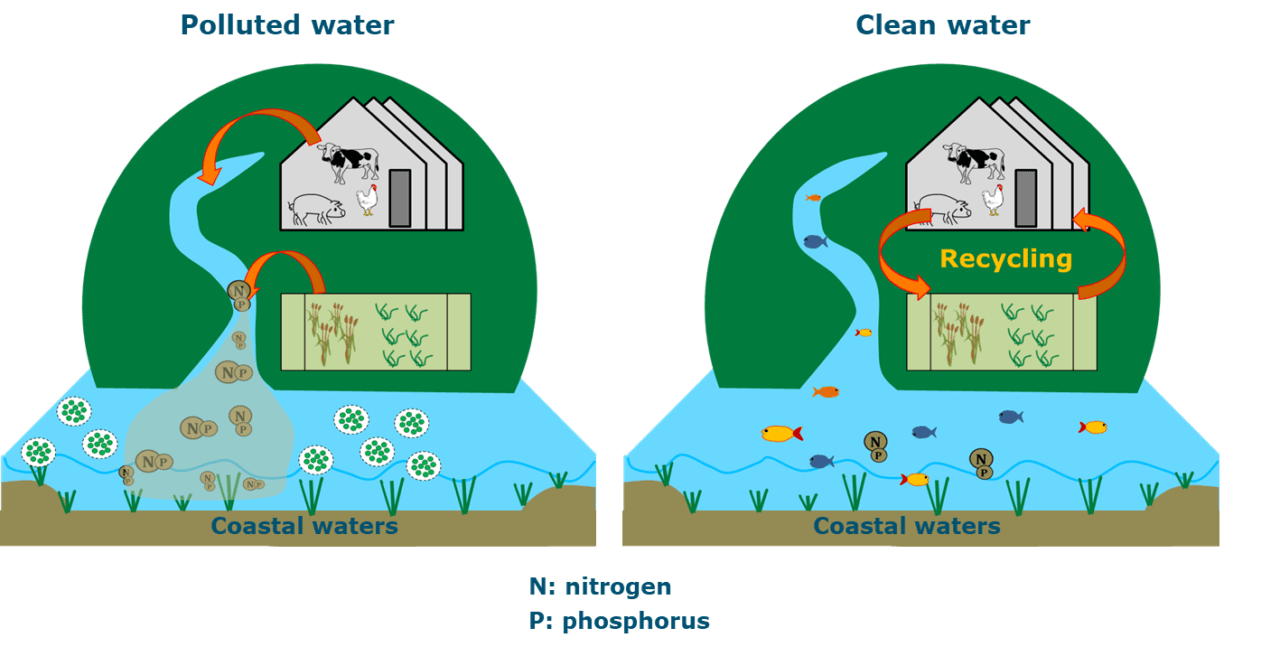

In our paper on this work, which was recently published in the journal Resources, Conservation, and Recycling, my colleagues and I conclude that reducing more than 80% of nutrient pollution in the Yangtze will cost US$ 1–3 billion in 2050. This cost might seem high, but it is actually far below 10% of the income level in the Yangtze basin. We also identified an opportunity in the negative or zero cost range, which would result in a below 80% reduction in nutrient export by the Yangtze. This negative or zero cost alternative involves options to recycle manure on land and reduce the use of chemical fertilizers (Figure 1). More recycling means that farmers will buy less chemical fertilizers and potential savings can then compensate for the expenses related to recycling the manure. We also illustrated the costs that would be involved for ten sub-basins to reduce their nutrient export to coastal waters.

Figure 1. Summarized illustration of eutrophication causes and cost-effective solutions for reducing nutrient export by Yangtze and thus coastal eutrophication in the East China Sea in 2050.

Recycling manure on cropland is an important and cost-effective solution for agriculture in the sub-basins of the Yangtze River (Figure 1). Manure is rich in the nutrients that crops need, and opting for this alternative instead of chemical fertilizers avoids loss of nutrients to rivers, and thus ultimately to coastal waters. Current practices are however still far from ideal, with manure – and especially liquid manure – often being discharged into water because crop and livestock farms are far away from each other, which makes it practically and economically difficult to transport manure to where it is needed. Another reason is the historical practice of farmers using chemical fertilizers on their crops – it is simply how they are used to doing things. Unfortunately, the amounts of fertilizers that farmers apply are often far above what crops actually need, thus leading to river pollution.

The Chinese government are investing in combining crop and livestock production, in other words, they are creating an agricultural sector where crops are used to feed animals and manure from the animals is in turn used to fertilize crops. Chinese scientists are working with farmers to implement these solutions.

In our paper, we showed that these solutions are not only sustainable, but also cost-effective in terms of avoiding coastal eutrophication. We invite you to read our paper for more details.

References

Strokal M, Kahil T, Wada Y, Albiac J, Bai Z, Ermolieva T, Langan S, Ma L, et al. (2020). Cost-effective management of coastal eutrophication: A case study for the Yangtze River basin. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 154: e104635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104635.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 11, 2019 | Alumni, Energy & Climate, IIASA Network, Water, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Lu Liu, postdoctoral research associate at Rice University, USA and IIASA YSSP 2016 participant

I have been attending the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting since 2013 when I was working with the Joint Global Change Research Institute. Ever since then, the AGU Fall Meeting has become one of my most anticipated events of the year where I get to share my research and make new friends.

The first time I attended the AGU Fall Meeting, I was overwhelmed with the size and scale of this conference. There are more than 20,000 oral and poster presentations throughout the week, and the topics cover nearly 30 different themes, from earth and space science, to education and public affairs. I was thrilled to see my research being valued and discussed by people from various backgrounds, and I was fascinated by other exciting research and rigorous ideas that emerged at the meeting.

Lu Liu at 2018 AGU poster session

At this year’s AGU, I presented my poster Implications of decentralizing urban water supply infrastructure via direct potable water reuse (DPR) in a session titled Water, Energy, and Society in Urban Systems. In a nutshell, my poster presents a quantitative model that evaluates the cost-benefits of direct potable water reuse in a decentralized water supply system. The concept of decentralization in an urban water system has been discussed in previous literature as an effective approach towards sustainable urban water management. Besides the social and technical barriers in implementing decentralization, there is a lack of analytical and computational tools necessary for the design, characterization, and evaluation of decentralized water supply infrastructure. My study bridges the gap by demonstrating the environmental and economic implications of decentralizing urban water infrastructure via DPR using a modeling framework developed in this study. The quantitative analysis suggests that with the appropriate configuration, decentralized DPR could potentially alleviate stress on freshwater and enhance urban water sustainability and resilience at a competitive cost. More about this research and my other work can be found here: https://emmaliulu.wixsite.com/luliu.

At the AGU Fall Meeting, I engaged in various opportunities to reconnect with old colleagues and build new professional relationships. What’s better than running into my former YSSP supervisors and IIASA colleagues after two years since I left the YSSP? Although my time spent at IIASA was short, I hold IIASA and the YSSP very close to my heart because the influence this experience has had on my professional and personal life is profound.

I will continue to attend the AGU Fall Meeting for the foreseeable future. After all, we all want to feel a sense of belonging and acceptance in a community, and I am glad I already found mine.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 20, 2018 | Systems Analysis, Water, Young Scientists

By Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Imagine you are heading home from work and are stuck in evening rush hour traffic. You see an opportunity to save time by cutting another driver off, but this will lead to a delay for other cars, possibly causing a traffic jam. Would you do it? Situations like these, where you can benefit from acting selfishly while causing the community as a whole to be worse off, are known as social dilemmas, and are at the heart of many areas of research in economics.

Tum Nhim (left) discusses water sharing with farmers and local authorities in rural Cambodia. © Tum Nhim

The social dilemma becomes particularly important when considering so-called common pool resources such as water reservoirs that are depleted when people use them. For instance, picture several farmers using water from the same river to irrigate their farmland. The river might carry enough water for all of them, but if there is no incentive for the upstream farmers to take the needs of the farmers living further downstream into consideration, they might use more than their share of the water, not leaving enough for the rest of the group. Situations like this are particularly relevant in developing countries, where small-scale farmers that manage the irrigation of their farmland themselves play a significant role in ensuring food security.

Growing up in southwestern Cambodia, YSSP participant Tum Nhim saw how the surrounding farmers shared water among themselves, and how important water was to their livelihoods. Not having enough water often meant that there were no crops for a whole year, and many farmers were forced to take on loans in order to feed their families. “Now that climate change is starting to affect Cambodia, and water scarcity is becoming an even bigger problem, it is more important than ever to investigate fair and efficient ways of sharing water,” explains Nhim.

As a water engineer, Nhim used to design and build water infrastructure. He however soon learned that not considering how human decision making affects the water supply will cause situations where the infrastructure provides enough water, but some farmers are still left high and dry. “I think that human behavior is the most important factor to consider when managing common pool resources,” he says.

To find possible solutions for distributing water in a way that yields an optimal outcome for the community, Nhim and his colleagues from the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program use a bottom-up approach–they model the behavior of a number of individual farmers that interact according to certain rules. The researchers can then look at the collective outcome of these interactions after a certain time and ask questions like, “Will the farmers cooperate?” or, “Will some farmers be left without water?” In their model the researchers take into account both the water itself, a common pool resource, and the water infrastructure, which is not depleted by use.

Several mechanisms can be used to ensure the fair distribution of water. Some of them are formal; like laws and regulations, but it is often difficult to keep people from extracting water, because using a given water resource might be a long-standing cultural tradition or legal right. There are however also more informal mechanisms that can help. For example, individuals often prefer to be good citizens in order to ensure that they have a high social standing in their community that will bring them benefits.

This reputational mechanism is especially relevant in small communities with everyday contact between members. If someone takes too much water, or doesn’t invest in the common water infrastructure, they will gain a bad reputation, which will in turn limit their ability to get support from their neighbors later on.

The main question Nhim is investigating in his YSSP project is if this mechanism can spread across several villages that share a common water resource and irrigation infrastructure, and lead to an outcome where everyone cooperates. If this turns out to be true, the reputational mechanism could be a very inexpensive and natural solution for managing common goods across several communities.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 7, 2017 | Data and Methods, Food, Postdoc, Water

By Valeria Javalera Rincón, IIASA CONACYT Postdoctoral Fellow in the Ecosystems Services and Management and Advanced Systems Analysis programs.

What is more important: water, energy, or food?

If you work in the water, energy or agriculture sector we can guess what your answer might be! But if you are a policy or decision maker trying to balance all three, then you know that it is getting more and more difficult to meet the growing demand for water, energy, and food with the natural resources available. The need for this balance was confirmed by the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, agreed by 193 countries, and the Paris climate agreement. But how to achieve it? Intelligent cooperation is the key.

The thing is that water, energy, and food are all related in such a way that are reliant on each other for production or distribution. This is the so-called Water-Energy-Food nexus. In many cases, you need water to produce energy, you need energy to pump water, and you need water and energy to produce, distribute, and conserve food.

Many scientists have tried to relate or to link models for water, agriculture, land, and energy to study these synergic relationships. In general, so far, there are two ways that this has been solved: One is integrating models with “hard linkages” like this:

© Daniel Javalera

In the picture there are six models (let’s say water, land use, hydro energy, gas, coal, food production models) that are then integrated into just one. The resulting integrated model then preserves the relationships but is complex, and in order to make it work with our current computer power you often have to sacrifice details.

Another way is to link them is using so-called “soft linkages” where the output of one model is the input of the next one, like this:

© Daniel Javalera

In the picture, each person is a model and the input is the amount of water left. These models all refer to a common resource (the water) and are connected using “soft linkages.” These linkages are based on sequential interaction, so there is no feedback, and no real synergy.

The intelligent linker agent

But what if we could have the relations and synergies between the models? It would mean much more accurate findings and helpful policy advice. Well, now we can. The secret is to link through an intelligent linker agent.

I developed a methodology in which an intelligent linker agent is used as a “negotiator” between models that can communicate with each other. This negotiator applies a machine-learning algorithm that gives it the capability to learn from the interactions with the models. Through these interactions, the intelligent linker can advise on globally optimal actions.

The knowledge of the intelligent linker is based on past experience and also on hypothetical future actions that are evaluated in a training process. This methodology has been used to link drinking water networks, such as Barcelona’s drinking water network.

When I came to IIASA, I was asked to apply this approach to optimize trading between cities in the Shanxi region of China. I used a set of previously development models which aimed to distribute water and land available for each city in order to produce food (eight types of crops) and coal for energy. The intelligent linker agent optimizes trading between cities in order to satisfy demand at the lowest cost for each city.

The purpose of this exercise was to compare the solutions with those from “hard linkages” – like those in the first picture. We found that the intelligent linker is flexible enough to find the optimal solution to questions such as: How much of each of these products should each city export/import to satisfy global demand at a global lower economic and ecological cost? What actions are optimal when the total production is insufficient to meet the total demand? Under what conditions is it preferable to stop imports/exports when production is insufficient to supply the demand of each city?

The answers to these questions can be calculated by the interaction with the models of each city just by the interfacing with the intelligent linker agent, this means that no major changes in the models of each city were needed. We also found that, under the same conditions, the solutions using the intelligent linker agent were in agreement with those found when hard linking was used.

My next challenge is to build a prototype of a “distributed computer platform,” which will allow us to link models on different computers in different parts of the world—so that we in Austria could link to a model built by colleagues in Brazil, for example. I also want to link models of different sectors and regions of the globe, in order to prove that intelligent cooperation is the key to improving global welfare.

References

Xu X, Gao J, Cao G-Y, Ermoliev Y, Ermolieva T, Kryazhimskiy AV, & Rovenskaya E (2015). Modeling water-energy-food nexus for planning energy and agriculture developments: case study of coal mining industry in Shanxi province, China. IIASA Interim Report. IIASA, Laxenburg, Austria: IR-15-020

Javalera V, Morcego B, & Puig V, Negotiation and Learning in distributed MPC of Large Scale Systems, Proceedings of the 2010 American Control Conference, Baltimore, MD, 2010, pp. 3168-3173. doi: 10.1109/ACC.2010.5530986

Valeria J, Morcego B, & Puig V, Distributed MPC for Large Scale Systems using Agent-based Reinforcement Learning, In IFAC Proceedings Volumes, Volume 43, Issue 8, 2010, Pages 597-602, ISSN 1474-6670, ISBN 9783902661913, https://doi.org/10.3182/20100712-3-FR-2020.00097.

Morcego B, Javalera V, Puig V, & Vito R (2014). Distributed MPC Using Reinforcement Learning Based Negotiation: Application to Large Scale Systems. In: Maestre J., Negenborn R. (eds) Distributed Model Predictive Control Made Easy. Intelligent Systems, Control and automation: Science and Engineering, vol 69. Springer, Dordrecht

Javalera Rincón V, Distributed large scale systems: a multi-agent RL-MPC architecture, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. Institut d’Organització i Control de Sistemes Industrials,Doctoral thesis. 2016. http://upcommons.upc.edu/handle/2117/96332

Note: This article gives the views of the author and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 25, 2017 | Water, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

Mexico City has been experiencing a major water crisis in the last few decades and it is only getting worse. To keep the water flowing, the city imports large amounts of water from as far as 150 kilometers.

Not only is this energy-intensive and expensive, it creates conflict with the indigenous communities in the donor basins. Over the last decade, a growing number of these communities have been protesting to reclaim their rights to water resources.

The ancient city of Tenochtitlan as depicted in a mural by Diego Rivera

(cc) Wikimedia Commons

As part of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program at IIASA, Francine van den Brandeler studied the struggle that Mexico City is facing as it tries to provide water to its growing population and expanding economy. Local aquifers have been over-exploited, so water needs to be imported from distant sources, with high economic, social, and environmental impacts. Van den Brandeler’s study assesses the effectiveness of water use rights in promoting sustainable water use and reducing groundwater exploitation in the city.

“A few centuries back, Tenochtitlan, the place where Mexico City stands today, was known as the lake city,” says Van den Brandeler. The Aztecs had developed a sophisticated system of dikes and canals to manage water and mitigate floods. However, that changed quickly with the arrival of the Spaniards, who transformed the natural hydrology of the valley. As the population continued to grow over the next centuries, providing drinking water became an increasing challenge, along with controlling floods. As the lake dried up, people pumped water from the ground and built increasingly large infrastructure to bring water from other areas.

Communities from lower-income groups, living in informal settlements on the outskirts of the metropolitan region are more vulnerable to this scarcity. Many live on just few liters of water every day, and do not have access to the main water supply network, instead relying on water trucks which charge several times the price of water from the public utility.

“In wealthier areas people consume much more than the average European does every day. It is a question of power and politics,” says van den Brandeler. “The voices of marginalized communities go unheard.”

Many people rely on delivery service for drinking water.

© Angela Ostafichuk | Shutterstock

The more one learns about the situation, the more complicated it becomes. The import of water started in the 1940’s. But with a massive increase in population in the last couple of decades, the deficits have become much worse.

The government’s approach has been to find more water rather than rehabilitating or reusing local surface and groundwater sources, or increasing water use efficiency, says van den Brandeler. Therefore wells are being drilled deeper and deeper—as much as 2000 meters into the ground—as the water runs out.

Some people have started initiatives to harvest rainwater, but it is not considered a viable solution by those in charge. “A lot of it has to do with their worldview and general paradigm. The people working at the National Water Commission and the Water Utility of Mexico City have been trained as engineers to make large dams and put pipes in the ground. They don’t believe in small-scale solutions. In their opinion when millions of people are concerned, such solutions cannot work,” says van den Brandeler.

Although the city gets plenty of rain during the rainy season, it goes directly into the drainage system which is linked to the sewage system. This contaminates the water, making it unusable. At the same time, almost 40% of the water in Mexico City’s piped networks is lost due to leakages.

Policy procedures and institutional functioning also remain top-down and opaque, van den Brandeler has found. One of the policy tools for curbing excess water use are water permits for bulk use, for agriculture, industry, or public utilities supplying water. Introduced in the 1940s, lack of proper enforcement has created misuse and conflicts.

For example, while farmers also require a permit that specifies the volume of water they may use each year, they do not pay for their water usage. However, it is difficult to monitor if farmers are extracting water according to the conditions in the permit. Since they do not pay a usage fee, there is also less incentive for the National Water Commission to monitor them. As a result, a huge black market has cropped up in the city where property owners and commercial developers pay exorbitant prices to buy water permits from those who have a license. Since the government allows the exchange of permits between two willing parties, they make it appear above-board. However, it has contributed to the inequalities in water distribution in the city.

With the water crisis worsening every year, Mexico City needs to find a solution before it runs out of water completely. Van den Brandeler is hopeful for a better future as she studies the contributing factors to the problem. She hopes that the water use permits are better enforced and users are given stronger incentives to respect their allocated water quotas. Further, if greater efforts are made within the metropolis to repair decaying infrastructure and scale up alternatives such as rainwater harvesting and wastewater reuse, the city won’t have to look at expensive solutions if adopted in a decentralized manner.

About the Researcher

Francine van den Brandeler is a third year PhD student at the University of Amsterdam in Netherlands. Her research is on the spatial mismatches between integrated river basin management and metropolitan water governance – the incompatibility of institutions and biophysical systems-, which can lead to fragmented water policy outcomes. Fragmented decision-making cannot adequately address the issues of sustainability and social inclusion faced by megacities in the Global South. She aims to assess the effectiveness of policy instruments to overcome this mismatch and suggest recommendations for policy (re)design. At IIASA she was part of the Water Program and worked under the supervision of Sylvia Tramberend and Water Program Director Simon Langan.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 7, 2017 | Climate Change, Food & Water, Water, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

In 2016, Bolivia saw its worst drought in nearly 30 years. While the city of La Paz faced an acute water shortage with no piped water in some parts, the agricultural sector was hit the hardest. According to The Agricultural Chamber of the East, the region suffered a loss of almost 50% of total produce. Animal carcasses lay scattered in plain sight in the valleys, where they had died looking for watering holes.

Lake Poopo (Bolivia) before it dried up © David Almeida I Flickr

One of the most dramatic results of this catastrophic drought was that Lake Poopo, (pronounced po-po) Bolivia’s second largest lake was drained of every drop of water. Located at a height of approximately 1127 meters, and covering an area of 1,000 square kilometers, what remains of it now resembles a desert more than a lake. This event forced the fishing community of Uru Uru, which depended on the lake, to either migrate to other lakes or look for alternate livelihood options.

Lake Poopo is located in the central South American Altiplano, one of the largest high plateaus in the world (Bolivia’s largest lake, Titicaca, is located in the north of the region). Due to its unique topography, the highland faces extreme climatic conditions, which are responsible for difficult lives as well as widespread poverty among the people who live there.

While Titicaca is over 100 meters deep, Poopo had a depth of less than three meters. Combined with a high rate of evapotranspiration, erratic rainfall, and limited flow of water from the Desaguadero River, Poopo was in a precarious position even during the best of times. Whatever little water flowed in from the river is further depleted by intensive irrigation activities at the south of Lake Titicaca before the water makes it way down to Poopo.

Sattelite images of Lake Poopo

Changes in water levels of Lake Poopo over 30 years © U.S. Geological Survey, Associated Press

The lake’s existence had been threatened several times in the past. However, the 2016 drought was one of the most devastating ones. According to the Defense Ministry of Bolivia, early this year the lake started recovering after several days of heavy rain, restoring as much as 70% of the water. However, since the lake is a part of a very fragile ecosystem, there have been some irreversible changes to the flora and fauna in addition to the losses to the fishing communities living around the lake.

Charting a better future

Claudia Canedo, a participant of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) at IIASA, is exploring the impact of droughts and the risk on agricultural production in the light of this event, after which Bolivia declared a state of water emergency. Canedo was born and raised in the city of La Paz and experienced water shortages while growing up close to the Altiplano. This motivated her to investigate a sustainable solution for water availability in the region. With the results of her study she is hoping to ensure that such a situation doesn’t arise again in the Altiplano – that other communities directly dependent on ecosystem services, like that of Lake Poopo, do not have to lose everything because of an extreme weather event.

For a region where more than half the population is dependent on agriculture for their livelihoods, droughts serve as a major setback to the national economy. “It is not just one factor that led to the drought, though. There were different factors that contributed to the drying up of the lake and also contribute to the agricultural distress,” she says.

“The southern Altiplano lies in an arid zone and receives low precipitation due to its proximity to the Atacama Desert. Poor soil quality (high saline content and lack of nutrients) makes it unsuitable for most crops, except quinoa and potato in some areas,” adds Canedo. Residents also lack the knowledge and the monetary resources to invest in newer technology, which could possibly lead to better water management.

A woman from one of the drought affected communities in Bolivia © EU – Photo credits: EC/ECHO/Laurence Bardon I Flickr

One of the most critical factors in the recent drought was the El Nino- Southern Oscillation, the warming of the sea temperatures in the Pacific Ocean, which in turn carries the warmer oceanic winds and lowers the rate of precipitation in the highland leading to increased evapotranspiration. In 2015 and 2016, the losses due to this phenomenon were devastating for agriculture in the Altiplano, says Canedo.

In her quest to find solutions, the biggest challenge is the lack of recorded data from local weather stations for the past years. Although satellite data is available, it is too generic in nature to do a local analysis. Therefore combining ground and satellite data could enhance the present knowledge and provide consistent results of the climate and vegetation variability. If done successfully, Canedo hopes to identify a correlation between precipitation and vegetation. With this information, she can improve climate forecasting that could help the local people adapt to droughts powerful enough to turn their lives upside down.

With weather forecasts and early warning systems for extreme weather events like droughts, farmers would know what to expect and would be able to plant resilient varieties of crops. This might not earn them the same profits as in a normal year, but would not result in a failed crop. Claudia aims to come up with a drought index useful for drought monitoring and early warning, which will integrate short-term and long-term meteorological predictions.

Perhaps, in the future, with this newfound knowledge, the price for extreme weather events won’t be paid in terms of lost ecosystems like that of Lake Poopo, robbing people of their lives and livelihoods.

About the Researcher

Claudia Canedo is a participant in the 2017 IIASA YSSP. She is pursuing a doctoral program in water resources engineering at Lund University, Sweden. She is interested in studying the hydrological and climatological conditions over small basins in the South American highlands. The aim of her research is to define water resources availability and find strategies for sustainable water management in the semi-arid region.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.