Aug 26, 2020 | Alumni, Climate Change, History, USA, Young Scientists

By Marcus Thomson, IIASA alumnus and a researcher at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), the University of California, Santa Barbara

IIASA alumnus Marcus Thomson explains how what we have learnt about prehistoric farming cultures can be used to provide useful insights on human societal responses to climate change.

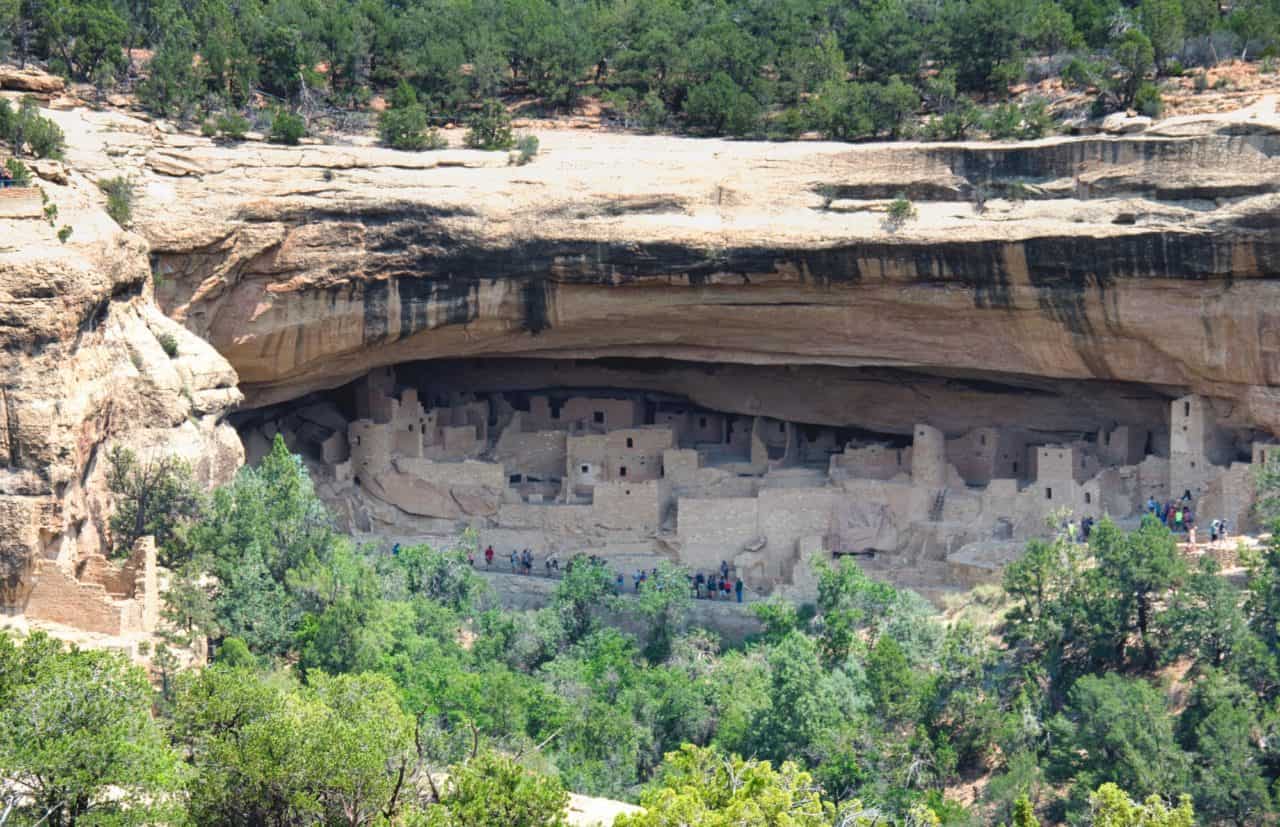

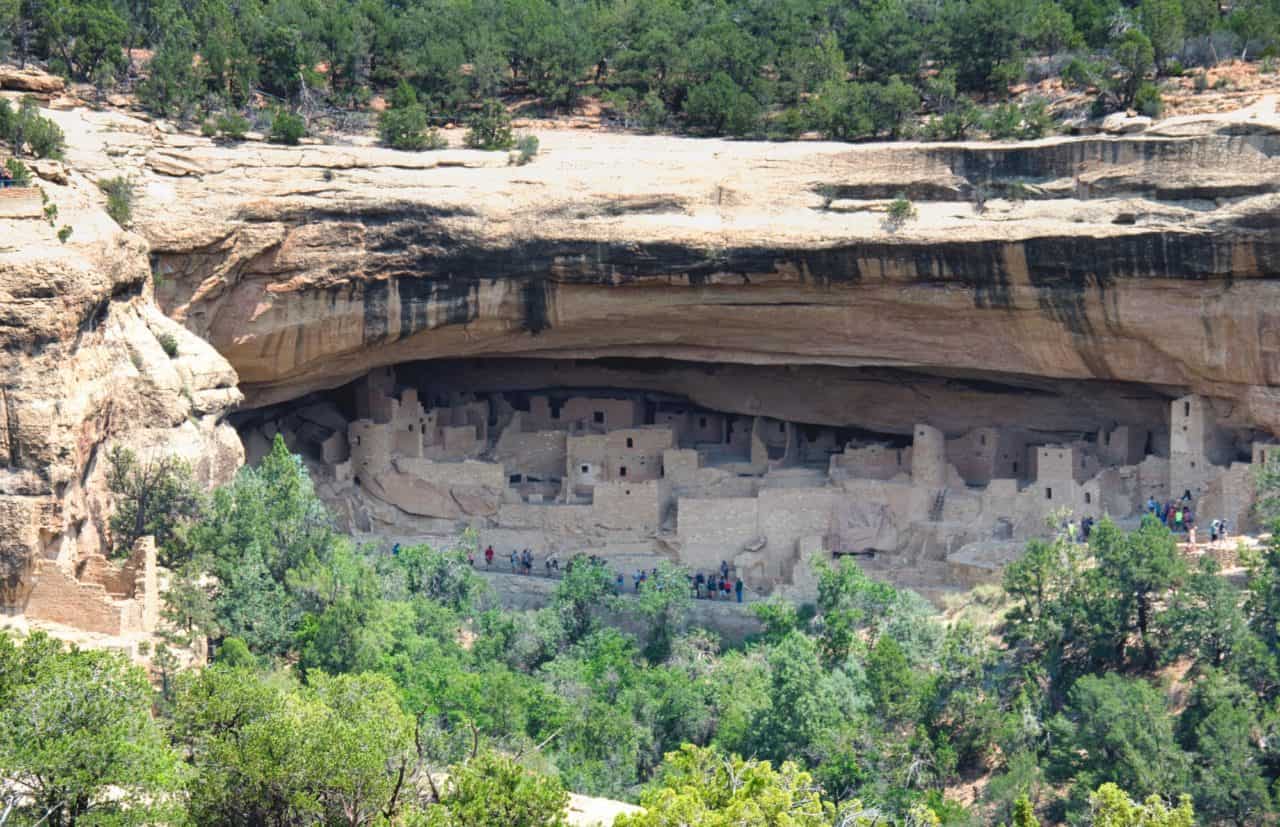

The climate of the western half of the North American continent, between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific coastal region, is dry by European standards. The American Southwest, in particular, centered roughly on the intersection of the states of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, is predominantly desert between high mountain plateaus. It is, and has always been, a challenging environment for farmers. Yet the prehistoric Southwest was home to complex maize-based agricultural societies. In fact, until the 19th century growth of industrial cities like New York, the Southwest contained ruins of the largest buildings north of Mexico — and these had been abandoned centuries before the Spanish arrived in the Americas.

© Mudwalker | Dreamstime.com

For more than a century, researchers have pored over data, from proxies of paleo-environmental change, to historiographies collected by explorers, to archaeology and computational models of human occupation, and produced a detailed picture of the socio-environmental, economic, and climatic conditions that could explain why these sites were abandoned. While details vary in fine-grained analyses of the various sub-groupings of peoples in the region, the big picture is one of societal transformation in adapting to climate change.

Also important is just how the climate changed during the period, because similar dynamics are expected to emerge in the future as a consequence of global warming. European historians point to a medieval era with generally warmer mean annual temperatures. In the Southwestern United States however, which is more sensitive to changes in drought than temperature, the period between roughly AD 850 to 1350 is known as the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA). The warm, dry MCA was followed by a long stretch of increased changes in the availability of water, known as the Little Ice Age (LIA). More frequent “warm droughts” at the end of the MCA, and generally increasing changes in water resources at the onset of the LIA, is thought to be a good analogy for future conditions in western North America.

When I had the good fortune to visit IIASA as a participant of the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) in 2016, I worked with research scholars Juraj Balkovič and Tamás Krisztin to develop a model of ancient Fremont Native American maize. The Fremont were an ancient forager-farmer people who lived in the vicinity of modern Utah. We used a climate model reconstruction of the temperature and rainfall between AD 850 and 1450 to drive this maize crop model, and compared modeled crop yields against changes in radiocarbon-derived occupations – in other words, the information gathered from carbon dated artifacts that show that an area was occupied by a particular people – from a few archaeological areas in Utah.

© Galyna Andrushko | Dreamstime.com

Among our findings was that changes in local temperatures appeared to play a larger role in the lives, practices and habits of the people who lived there than changes in regional, long-term temperature conditions [1]. Later, while a researcher at IIASA myself, I returned to the subject with one of our coauthors, professor Glen MacDonald of the University of California, Los Angeles, using an expanded geographic range and a more sophisticated treatment of radiocarbon dated occupation likelihoods.

We used the climate model to reconstruct prehistoric maize growing season lengths and mean annual rainfall for Fremont sites. We found that the most populous and resilient Fremont communities were at sites with low-variability season lengths; and low populations coincided with, or followed, periods of variable season lengths. This study confirmed the important dependence on climate variability; and more importantly, our results are in line with others on modern smallholder farming contexts.

More details on our latest study [2] have just been published online in Environmental Research Letters (ERL). It will become part of an ERL special issue looking at societal resilience drawing lessons from the past 5000 years. Studies like these can give useful insights on human societal responses to climate change because these ancient civilizations are, in a sense, completed experiments with complex human-environmental systems. For decision makers, who must plan early to commit resources to offset the effects of future climate change on smallholder farmers in similarly drought-sensitive, marginally productive environments, these studies indicate that year-to-year climatic variability drives occupation change more than long-term temperature change.

References:

[1] Thomson MJ, Balkovič J, Krisztin T, & MacDonald GM (2019). Simulated impact of paleoclimate change on Fremont Native American maize farming in Utah, 850–1449 CE, using crop and climate models. Quaternary International, 507, pp.95-107 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15472]

[2] Thomson MJ, & MacDonald GM (In press). Climate and growing season variability impacted the intensity and distribution of Fremont maize farmers during and after the Medieval Climate Anomaly based on a statistically downscaled climate model. Environmental Research Letters.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 5, 2018 | Climate, Climate Change, Ecosystems, Environment, Food, Food & Water, History, Young Scientists

© Marcus Thomson

By Marcus Thomson, researcher, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

While living in Cairo in 2010, I witnessed first-hand the human toll of political and environmental disasters that washed over Africa at the end of the last century. Unprecedented numbers of migrants were pressing into North Africa, many pushed out of their homelands by conflict and state-failure, pulled towards safer, richer, less fragile places like Europe. Throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, climate change was driving up competition for scarce land and water, and raising pressure on farmers to maintain the quantity and quality of their crops.

It is a similar story throughout the developing world, where many farmers do without the use of expensive chemical fertilizer and pesticides, complex irrigation, or boutique seed varieties. They rely instead on traditional land management practices that developed over long periods with consistent, predictable conditions. It is difficult to predict how dryland farmers will respond to climate change; so it is challenging to plan for various social, economic, and political problems expected to develop under, or be exacerbated by, climate change. Will it spur innovation or, as has been argued for the Syrian civil war[1], set up conflict? A major stumbling block is that the dynamics of human social behavior are so difficult to model.

Instead of attempting to predict farmers’ responses to climate change by modelling human behavior, we can look to the responses to environmental changes of farmers from the past as analogues for many subsistence farmers of the future. Methods to fill in historical gaps, and reconstruct the prehistoric record, are valuable because they expand the set of observed cases of societal-scale responses to environmental change. For instance, some 2000 years ago, an expansive maize-growing cultural complex, the Ancestral Puebloans (APs), was well established in the arid American Southwest. By AD 1000, members of this AP complex produced unique and innovative material culture including the famed “Great Houses”, the largest built structures in the United States until the 19th century. However, between AD 1150 and 1350, there was a profound demographic transformation throughout the Southwest linked to climate change. We now know that many APs migrated elsewhere. As a PhD student at the University of California, Los Angeles, I wondered whether a shift to cooler, more variable conditions of the “Little Ice Age” (LIA, roughly AD 1300 to 1850) was linked to the production of their staple crop, maize.

I came to IIASA as a YSSP in 2016 to collaborate with crop modelers on this question, and our work has just been published in the journal Quaternary International.[2] I brought with me high-resolution data from a state-of-the-art climate model to drive the crop simulations, and AP site information collected by archaeologists. Because AP maize was quite different from modern corn, I worked with IIASA soil scientist Juraj Balkovič to modify the crop simulator with parameters derived from heirloom varieties still grown by indigenous peoples in the Southwest. I and IIASA economic geographer Tamás Krisztin developed a statistical technique to analyze the dynamical relationship between AP site occupation and simulated yield outcomes.

We found that for the most climate-stressed high-elevation sites, abandonments were most associated with increased year-to-year yield variability; and for the least stressed low-elevation and well-watered sites, abandonment was more likely due to endogenous stressors, such as soil degradation and population pressure. Crucially, we found that across all regions, populations peaked during periods of the most stable year-to-year crop yields, even though these were also relatively warm and dry periods. In short, we found that AP maize farmers adapted well to gradually rising temperatures and drought, during the MCA, but failed to adapt to increased climate variability after ~AD 1150, during the LIA. Because increased variability is one of the near certainties for dryland farming zones under global warming, the AP experience offers a cautionary example of the limits of low-technology adaptation to climate change, a business-as-usual direction for many sub-Saharan dryland farmers.

This is a lesson from the past that policymakers might take note of.

[1] Kelley, C. P., Mohtadi, S., Cane, M. A., Seager, R., & Kushnir, Y. (2015). Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201421533.

[2] Thomson, M. J., Balkovič, J., Krisztin, T., MacDonald, G. M. (2018). Simulated crop yield for Zea mays for Fremont Ancestral Puebloan sites in Utah between 850-1499 CE based on temperature dailies from a statistically downscaled climate model. Quaternary International. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2018.09.031

Jun 26, 2018 | History, Science and Policy

By Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

In his lecture at IIASA, Maurizio Bona, senior advisor for relations with parliaments and science for policy, and senior advisor on knowledge transfer at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) discussed the question “Science and diplomacy–two different worlds?”, focusing on the dual role of CERN as both a research laboratory and an intergovernmental institution.

Maurizio Bona ©CERN

According to Bona, international research centers like CERN and IIASA foster international and intercultural communication by bringing together people with different backgrounds and ideas to work on a common goal. In this context, these organizations act as communication channels where science is used as a universal language.

CERN was established in 1953 to carry out research on particle physics, but also to reunite a Europe that was divided after World War II, and to re-open the dialogue between European countries and beyond. While CERN was not involved in politics directly, an important point of the lecture was that science can provide a neutral field for dialogue and connect people that would not meet otherwise. In this way, international research institutes can contribute to science diplomacy in a very indirect and informal way.

IIASA was founded in 1972 to find solutions to global problems, and with a similar goal of using scientific cooperation to build bridges across the Cold War divide. Despite the vastly different research done at CERN and IIASA, both organizations have roots in science diplomacy that stem from the fact that today’s problems, regardless of whether they are fundamental or applied in nature, are often too complex to be solved by one country or discipline alone.

Even though CERN is a European organization, it attracts researchers from all over the world, like IIASA. In January 2018, 41% of scientific users (researchers using CERN facilities that are not paid by CERN) were from non-member countries and contributed their expertise as well as research equipment. In order to ensure that scientific advancement and not national interests are the basis of the research objectives at CERN, it is based on a simple but strong Convention that excludes military applications and ensures transparency. Additionally, CERN stays away from political affiliations.

Based on the success of the CERN model, the first particle accelerator in the Middle East, Synchrotron-Light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East (SESAME), was established in 2004. Its organizational structure is based largely on that of CERN, and it was thought out explicitly as a way to bring together conflicting Middle Eastern countries, while at the same time advancing science. SESAME’s member states are Cyprus, Egypt, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Pakistan, Palestine, and Turkey and the facility has been open to scientific users from the Middle East and beyond since 2017.

Beyond fostering international and intercultural communication by bringing together people with different backgrounds and ideas to work on a common goal, international research institutes can also influence policy more directly. For example, CERN has been an observing member at the UN general assembly since 2012 and has had an influence on shaping the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, advocating for the importance of education and fundamental research.

IIASA goes one step further, explicitly aiming to shape policies and help politicians make informed, evidence-based decisions. IIASA research has for example shaped European air pollution policy and has led to real improvements in the sustainable management of scarce resources in a number of countries. The institute’s independence and political neutrality are key for its credibility as an adviser to policy makers. IIASA is nongovernmental and is instead sponsored by its 23 national member organizations. Today IIASA member countries make up 71% of the global economy and 63% of the global population, making IIASA particularly well-suited to address global challenges.

Maurizio Bona closed his lecture with the following quote by Daniel Barenboim, a world-famous pianist and conductor:

“Let me tell you something: This is not going to bring peace. What it can bring is understanding, the patience, the courage, and the curiosity to listen to the narrative of the other.”

Daniel Barenboim, Ramallah concert, August 2005.

This quote was originally meant to be understood in the context of international collaboration in music, but is also applicable to science, and in fact to any endeavor that brings together people from different backgrounds to work towards a common goal.

The lecture left the audience with some open questions, like how to measure the impact of science on society, or how involved science should be in diplomacy. Some of these questions were picked up on in a lively discussion after the talk. For now, I think it is fair to conclude that the histories of both CERN and IIASA show that international research institutes can have a positive impact on society while remaining politically neutral and unbiased in their scientific goals.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 6, 2014 | Alumni, History

By Aviott John, IIASA alumnus

Anyone who has seen before and after photos of Schloss Laxenburg—the home of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)—knows what an incredible physical transformation the building went through between 1972 and 1981 to become the home of IIASA.

Aviott John with his daughter Megala. He worked at IIASA for 37 years.

The functional and organizational changes that happened inside Schloss Laxenburg as IIASA developed, were just as striking as the physical ones. Here was an abstract idea taking shape, not only in the wood and stone of Schloss Laxenburg, but in the various actions of people; in the recruitment of staff from more than 40 different nationalities who had never worked together before; in joint study programs to discover how large organizations work successfully under different political systems; and in the solution of common ecological problems in different parts of the world. No less important were the social interactions that formed the basis for deep friendships that ultimately provide the glue for successful international relations

Today the word globalization slips glibly off the tongue. The ability to travel was not so taken for granted in the world of the 1970s. There were many reasons for that, the most obvious being the political systems in place at the time and the relatively high financial cost of air travel. Today the challenge the Institute must face is perhaps not the financial cost of air travel, but its environmental cost. The Institute no longer just works across the divide between East and Western Europe as in Cold War days, but now across the barriers between developed and developing countries, on all continents of the world. And so the transformations continue. I feel privileged to have been an observer of some of these transformations for 37 years.

IIASA Alumni Day will take place on April 29, 2014, and we are inviting alumni to send their memories and photos of their time at IIASA. This post comes from Aviott John, longtime IIASA employee in the library and communications departments, who retired last year. To contribute, please contact IIASA Development Assistant Deirdre Zeller.

Before: View of the inner courtyard of Schloss Laxenburg, 1962

After: View of the Schloss Laxenburg inner courtyard after renovation in 1978

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.