Aug 26, 2020 | Alumni, Climate Change, History, USA, Young Scientists

By Marcus Thomson, IIASA alumnus and a researcher at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), the University of California, Santa Barbara

IIASA alumnus Marcus Thomson explains how what we have learnt about prehistoric farming cultures can be used to provide useful insights on human societal responses to climate change.

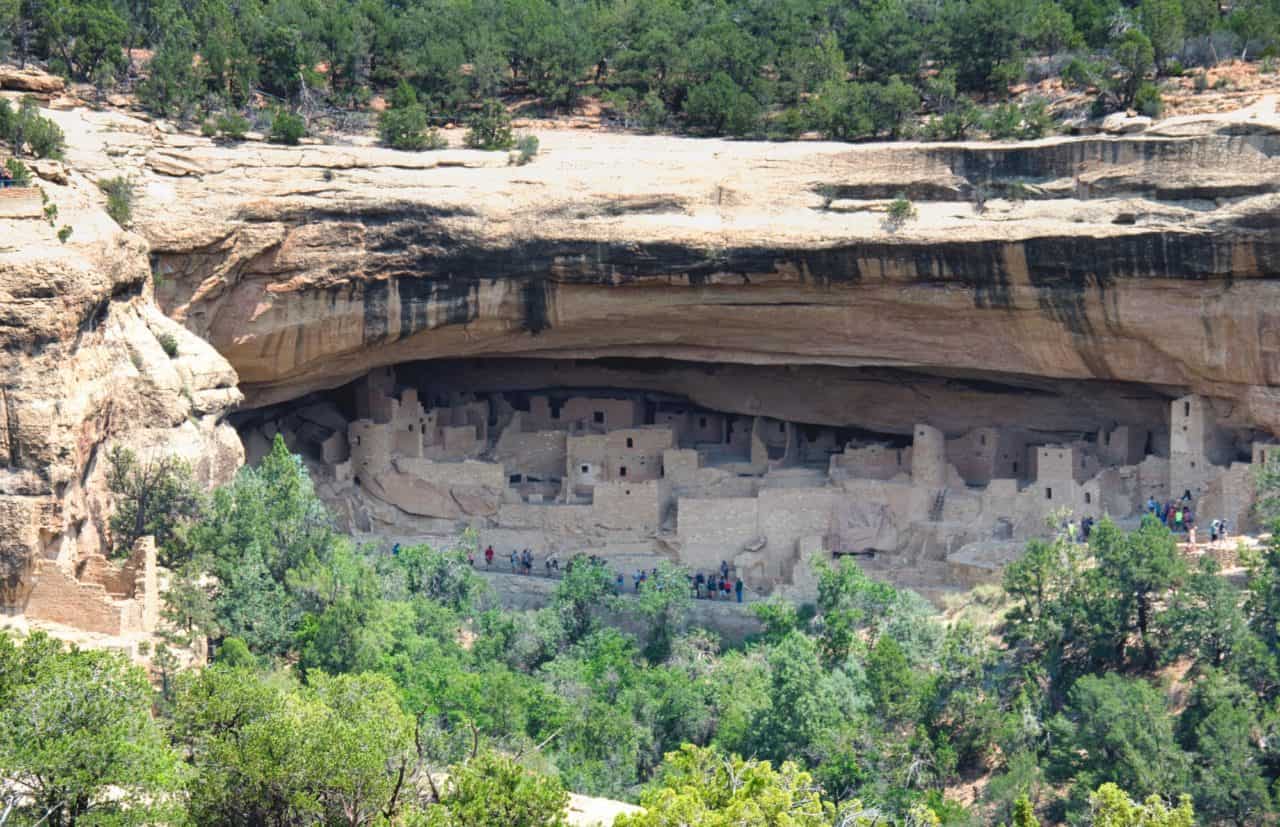

The climate of the western half of the North American continent, between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific coastal region, is dry by European standards. The American Southwest, in particular, centered roughly on the intersection of the states of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, is predominantly desert between high mountain plateaus. It is, and has always been, a challenging environment for farmers. Yet the prehistoric Southwest was home to complex maize-based agricultural societies. In fact, until the 19th century growth of industrial cities like New York, the Southwest contained ruins of the largest buildings north of Mexico — and these had been abandoned centuries before the Spanish arrived in the Americas.

© Mudwalker | Dreamstime.com

For more than a century, researchers have pored over data, from proxies of paleo-environmental change, to historiographies collected by explorers, to archaeology and computational models of human occupation, and produced a detailed picture of the socio-environmental, economic, and climatic conditions that could explain why these sites were abandoned. While details vary in fine-grained analyses of the various sub-groupings of peoples in the region, the big picture is one of societal transformation in adapting to climate change.

Also important is just how the climate changed during the period, because similar dynamics are expected to emerge in the future as a consequence of global warming. European historians point to a medieval era with generally warmer mean annual temperatures. In the Southwestern United States however, which is more sensitive to changes in drought than temperature, the period between roughly AD 850 to 1350 is known as the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA). The warm, dry MCA was followed by a long stretch of increased changes in the availability of water, known as the Little Ice Age (LIA). More frequent “warm droughts” at the end of the MCA, and generally increasing changes in water resources at the onset of the LIA, is thought to be a good analogy for future conditions in western North America.

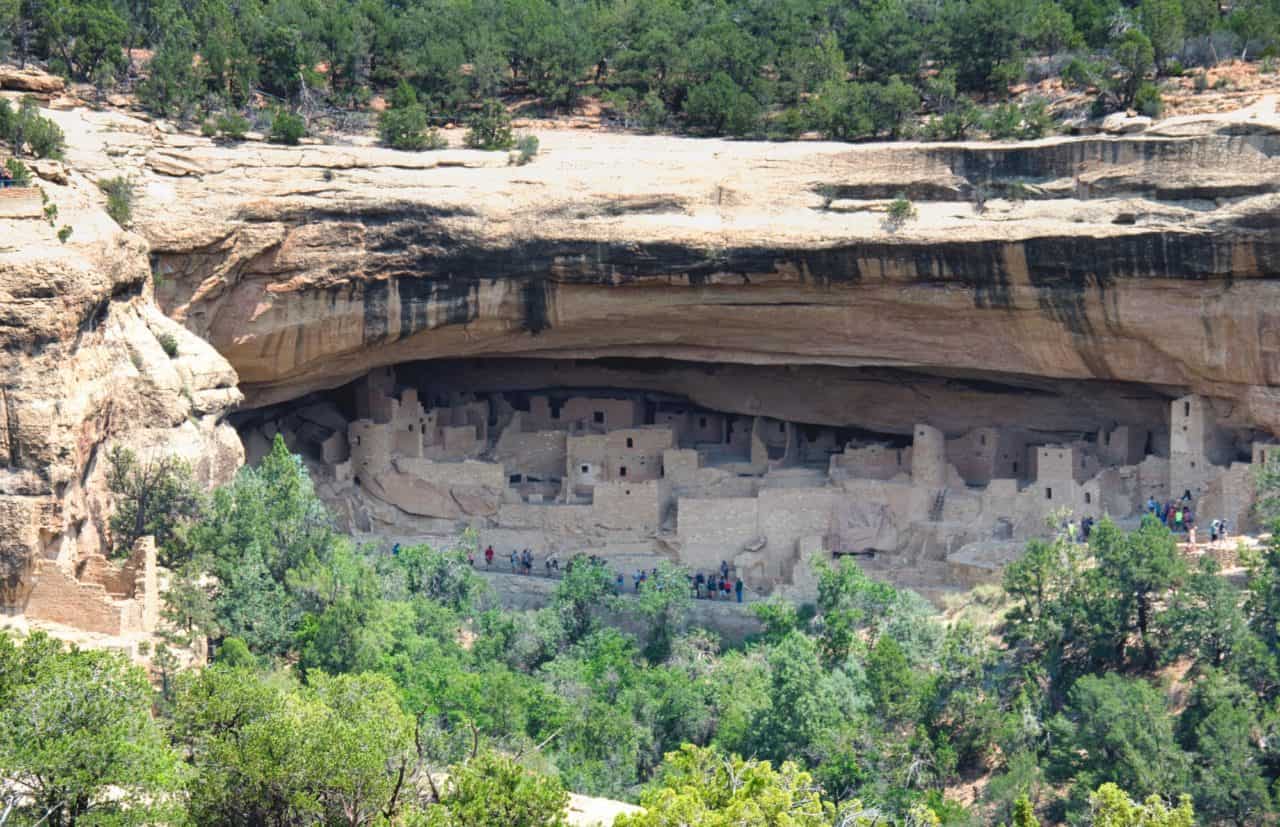

When I had the good fortune to visit IIASA as a participant of the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) in 2016, I worked with research scholars Juraj Balkovič and Tamás Krisztin to develop a model of ancient Fremont Native American maize. The Fremont were an ancient forager-farmer people who lived in the vicinity of modern Utah. We used a climate model reconstruction of the temperature and rainfall between AD 850 and 1450 to drive this maize crop model, and compared modeled crop yields against changes in radiocarbon-derived occupations – in other words, the information gathered from carbon dated artifacts that show that an area was occupied by a particular people – from a few archaeological areas in Utah.

© Galyna Andrushko | Dreamstime.com

Among our findings was that changes in local temperatures appeared to play a larger role in the lives, practices and habits of the people who lived there than changes in regional, long-term temperature conditions [1]. Later, while a researcher at IIASA myself, I returned to the subject with one of our coauthors, professor Glen MacDonald of the University of California, Los Angeles, using an expanded geographic range and a more sophisticated treatment of radiocarbon dated occupation likelihoods.

We used the climate model to reconstruct prehistoric maize growing season lengths and mean annual rainfall for Fremont sites. We found that the most populous and resilient Fremont communities were at sites with low-variability season lengths; and low populations coincided with, or followed, periods of variable season lengths. This study confirmed the important dependence on climate variability; and more importantly, our results are in line with others on modern smallholder farming contexts.

More details on our latest study [2] have just been published online in Environmental Research Letters (ERL). It will become part of an ERL special issue looking at societal resilience drawing lessons from the past 5000 years. Studies like these can give useful insights on human societal responses to climate change because these ancient civilizations are, in a sense, completed experiments with complex human-environmental systems. For decision makers, who must plan early to commit resources to offset the effects of future climate change on smallholder farmers in similarly drought-sensitive, marginally productive environments, these studies indicate that year-to-year climatic variability drives occupation change more than long-term temperature change.

References:

[1] Thomson MJ, Balkovič J, Krisztin T, & MacDonald GM (2019). Simulated impact of paleoclimate change on Fremont Native American maize farming in Utah, 850–1449 CE, using crop and climate models. Quaternary International, 507, pp.95-107 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15472]

[2] Thomson MJ, & MacDonald GM (In press). Climate and growing season variability impacted the intensity and distribution of Fremont maize farmers during and after the Medieval Climate Anomaly based on a statistically downscaled climate model. Environmental Research Letters.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 19, 2020 | Climate Change, COVID19, USA, Wellbeing, Young Scientists

By Lisa Thalheimer, 2020 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant in the Risk and Resilience and World Population Programs

Lisa Thalheimer shares her journey in researching climate-related migration in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic and the importance of taking mental health issues into account in climate science and the policy realm.

© Raul Mellado Ortiz | Dreamstime.com

COVID-19 has changed our idea of normal. These unprecedented, stressful times affect us all – some of us more than others. Fear and anxiety over a new disease without any promise of a vaccine anytime soon, global economic downturn, along with feelings of loneliness and emotional exhaustion due to the lockdown, can leave us mentally exhausted. Rates of depression and addiction-related suicide are in fact already on the rise among young people like myself.

Now imagine you are advised to stay at home, but you cannot do so because climate change has turned your entire life upside down: your house is no longer there, you have lost your job, your family or friends – you are likely to feel unhinged. This is a reality for many migrants across the globe. It is inevitable that existing migration patterns will be shifted beyond disasters alone. Cascading impacts form the still unfolding pandemic could compound. No matter if you are a migrant yourself or not, agency and the choice over the decision whether to leave your house or not, and the luxury to socially distance could potentially not be an option with a systemic shock like COVID-19.

These changes in circumstances have also affected me as a young scientist. I would have been in Laxenburg, getting to know my YSSP peers and IIASA colleagues, but this year’s journey has been rewritten – courtesy of the COVID-19 pandemic.

I was living in Oxford in the UK when I came to realise that mental health is a game changer in the way I manage my day, make decisions, my ability to care for my partner who suffers from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), and making progress on my PhD thesis. Everything felt more difficult. I was overwhelmed. I wanted to understand why this is the case. My interest soon evolved into researching the links between mental health and my PhD topic of climate-related migration.

For the article “The hidden burden of pandemics, climate change and migration on mental health”, I teamed up with an epidemiologist who specialises in mental health at my old university home, the Earth Institute in New York City. This research experience was an eye-opener, both personally and scientifically.

In our article, we focused on the US, as it has been hit hardest by COVID-19 – in mid-August, the number of COVID-19 cases exceeded five million. On top of this, depression and anxiety are already prominent among Americans, as is costly impacts from disasters. Hurricanes cost the US around US$ 17 billion every year, but estimates show a higher probability of extremely damaging hurricane seasons with climate change. We may know the impact of climate change on assets and on physical health, but what about mental health impacts?

© Raggedstonedesign | Dreamstime.com

Although my coauthor and I come from different scientific disciplines, I soon came to realize that our scientific approach has a common denominator: systems thinking. Accounting for interconnections and cascading effects, our article shed light on different systems affected by COVID-19 and situations where mental health issues are likely to become increasingly prevalent in a changing climate. The article focuses on already vulnerable parts of the population, for example those who have been impacted by Hurricane Katrina or Hurricane Harvey – the latter of which has been made worse by climate change. The article illustrates how COVID-19 becomes a risk multiplier for climate migrants in three distinct case studies: key workers in New York as urban setting, seasonal migration dynamics, and disproportionate effects on black and Latino communities. Unrelenting effects include loss of employment, and a lower likelihood of being able to work from home or to have health insurance than white people.

A better understanding of the mental health-migration-climate change nexus can help absorb adverse mental health outcomes from COVID-19, which would otherwise compound. We however need to tackle systemic risks affecting mental health through synergies in research and policy, and an integrated intervention approach. Free mental health support for key workers through tele-therapy and mental health hotlines provide a practical way forward. Personally, I learned that climate migrants have been relentlessly resilient to systemic shocks. Nevertheless, with mental health issues, it becomes increasingly hard to maintain such resilience. With this commentary, I hope that mental health and interdisciplinary research finds its way in climate science and in the policy realm. We all need a clear mind to attain the Sustainable Development Goals.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 11, 2019 | IIASA Network, USA, Women in Science

Rachel Potter, IIASA communications officer, interviews retired NASA Astronaut and Principal of AstroPlanetview LLC, Sandra H Magnus on insights about our world she has gained from her time living on the International Space Station.

©NASA Photo / Houston Chronicle, Smiley N. Pool

Q: Can you tell us a bit about your specific areas of research as a scientist?

A: My PhD was on a new material system being investigated for thermionic cathodes, which are used as electron sources for satellite communication systems. My research was an effort to look at the system methodically and from a science viewpoint to understand physically what was going on in order to inform the design of more robust devices. If you can operate the cathode at a lower temperature, that means a longer life for it, which is a good thing for satellites! Post-PhD I was however admitted to the Astronaut Office and that, quite frankly, pretty much put an end to my career as a researcher, or at least as a principal investigator (PI). The work I did on the International Space Station was at the direction of other PIs who had proposed, and been granted, experiments in space.

Q: Your career has spanned a wide range of settings from the NASA Astronaut Corps to your current role as Principal of AstroPlanetview LLC – what is the common thread or focus that has run through your work?

A: Following my curiosity and looking for challenges. I always want to be challenged and feel that I am learning new things. If I feel that I have become stagnant, I start looking for how to change that situation.

Q: What have been the personal highlights of your career?

A: Clearly flying in space! I feel very fortunate, however, to have been in the Astronaut Office during the era of the space station. I enjoyed very much working in a collaborative, multicultural, international environment where we had a big team of people from around the world working on something that benefits the planet.

Q: What are the greatest lessons you have learned from seeing the Earth from space?

A: I was so excited to FINALLY be going into space after hoping to do just that for over 20 years. The Earth is our spaceship – a closed system in which everything on the planet affects, and is connected to everything else on the planet. An action somewhere means a reaction somewhere else, even if it is not always first order (and usually it is not). Also, the planet looks incredibly beautiful and very fragile – we have to take care of it!

© NASA STS-126 Shuttle Mission full crew photo (5 March 2008), Sandra H Magnus far left.

Q: What do you see as key to solving the complex problems the Earth faces in terms of sustainability?

A: Having the will to do it as a community. If you have the will, commitment and a clear, agreed-to, articulation of the common goal, we can pretty much accomplish anything we want to.

Q: How do you see IIASA being able to build bridges between countries across political divides?

A: Well, when we want to solve problems, it really is all about relationships at the end of the day. It is easy to demonize or keep your distance from abstract ideas or the ubiquitous “They” but when you meet people, understand them as individuals and the context of their backgrounds that lead them to have different views and approaches to life and solving problems, it is much easier to visualize how you can work together to tackle issues. The relationships are the bridges.

Q: What advice would you give to young women researchers wanting to make it into Aeronautics?

A: To young women (and young men, too, really) I would say, “If you have a dream to go do something, then you owe it to yourself to go for it and try it!” Never let anyone else define who you are or tell you what you can or cannot do – believe in yourself and give it a try. Maybe you will make it, maybe you will not, but it will be on your own terms, with you pushing yourself and regardless of the outcome you will have a deeper understanding of yourself, and that is always a good thing.

Sandra H Magnus visited IIASA on 21 June 2019 in cooperation with the US Embassy Vienna, to give a lecture entitled “Perspectives from Space” to IIASA staff and this year’s participants of the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program. IIASA has a worldwide network of collaborators who contribute to research by collecting, processing, and evaluating local and regional data that are integrated into IIASA models. The institute has 819 research partner institutions in member countries and works with research funders, academic institutions, policymakers, and individual researchers in national member organizations.

Notes:

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 29, 2019 | USA, Young Scientists

By Matt Cooper, PhD student at the Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Maryland, and 2018 winner of the IIASA Peccei Award

I never pictured myself working in Europe. I have always been an eager traveler, and I spent many years living, working and doing fieldwork in Africa and Asia before starting my PhD. I was interested in topics like international development, environmental conservation, public health, and smallholder agriculture. These interests led me to my MA research in Mali, working for an NGO in Nairobi, and to helping found a National Park in the Philippines. But Europe seemed like a remote possibility. That was at least until fall 2017, when I was looking for opportunities to get abroad and gain some research experience for the following summer. I was worried that I wouldn’t find many opportunities, because my PhD research was different from what I had previously done. Rather than interviewing farmers or measuring trees in the field myself, I was running global models using data from satellites and other projects. Since most funding for PhD students is for fieldwork, I wasn’t sure what kind of opportunities I would find. However, luckily, I heard about an interesting opportunity called the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) at IIASA, and I decided to apply.

Participating in the YSSP turned out to be a great experience, both personally and professionally. Vienna is a wonderful city to live in, and I quickly made friends with my fellow YSSPers. Every weekend was filled with trips to the Alps or to nearby countries, and IIASA offers all sorts of activities during the week, from cultural festivals to triathlons. I also received very helpful advice and research instruction from my supervisors at IIASA, who brought a wealth of experience to my research topic. It felt very much as if I had found my kind of people among the international PhD students and academics at IIASA. Freed from the distractions of teaching, I was also able to focus 100% on my research and I conducted the largest-ever analysis of drought and child malnutrition.

© Matt Cooper

Now, I am very grateful to have another summer at IIASA coming up, thanks to the Peccei Award. I will again focus on the impact climate shocks like drought have on child health. however, I will build on last year’s research by looking at future scenarios of climate change and economic development. Will greater prosperity offset the impacts of severe droughts and flooding on children in developing countries? Or does climate change pose a hazard that will offset the global health gains of the past few decades? These are the questions that I hope to answer during the coming summer, where my research will benefit from many of the future scenarios already developed at IIASA.

I can’t think of a better research institute to conduct this kind of systemic, global research than IIASA, and I can’t picture a more enjoyable place to live for a summer than Vienna.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.