Oct 18, 2021 | Climate, Climate Change, Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Marina Andrijevic, researcher in the IIASA Energy, Climate, and Environment Program

Marina Andrijevic tackles some inconvenient but fundamental issues around climate change adaptation.

© Lio2012 | Dreamstime.com

Anyone who followed climate-related headlines this summer would have noticed a more than usual amount of talk on climate change adaptation. As it goes with sudden epiphanies in aftermaths of humanitarian disasters in our Western realities, this time we’ve come to realize that we need to seriously think about doing some adaptation.

To be fair, the realization that adaptation is inevitable has for a long time been somewhat of a taboo in the “woke” climate policy and activist circles (the author of this blog is a millennial and would like to acknowledge that the reader’s idea of a long time in climate policy might be different). Admitting that there might be no other option but to adapt to whatever the locked-in effects of climate change are, is arguably defeatist and gives in to the notion that mitigation alone won’t cut it.

While this might be yet another depressing but accurate reflection of the reality under climate change, portraying adaptation and mitigation as different but equally urgent actions could set a dangerous trap if it produces ideas such as: if we adapt enough, perhaps our economies and energy systems won’t need to change so much.

Even if it would be enough (which it wouldn’t), adaptation will not necessarily just happen once we recognize it needs to be done, because the needs and abilities for it operate on different time horizons and geographical scales. Many parts of the world that need adaptation will not necessarily be able to take action, so we have to be very careful when we count on it as a solution to climate change.

This is where we must tackle some inconvenient but fundamental issues about adaptation. Climate change research, especially the areas positioned at the “interface” with policy, could play a crucial role here. In this role, it must be very prudent and avoid doing a disservice to decision makers, and even worse, to people affected by those decisions. In other words, the scientific assessments need to be careful when assuming for whom, where, and how adaptation can reasonably be expected.

We tried to illustrate why this matters in our recent paper that looks at the capacity of populations to adapt to heat stress. We used air-conditioning as a popular, albeit not (yet) climate-friendly adaptation option. My coauthors and I understand that air conditioning could well be maladaptation, meaning that it causes more harm than good in the long-run. Adaptation practices, however, it turns out, are quite difficult to measure, while installed air conditioners can literally be counted, which makes them handy for plugging into our statistical models. We contend with access to air conditioning currently being a good enough example of access to adaptation and promise to assess more options in the future.

Our paper shows how the capacities to protect against heat stress vary widely around the world. Like with many other unjust manifestations of climate change, people in the world’s hottest areas also have the least means to adapt. We found that countries with more income, more urban areas, and less income inequality, are also the ones where more people have access to air conditioning.

This does not come as the world’s biggest revelation, but it conveniently allows us to make informed guesses on how access to air conditioning might change in 2050 or 2100. This is possible because the research community has already engaged in a group effort to propose five different futures with regard to GDP, urbanization, and income distribution (in climate jargon: the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways or SSPs).

Coupling the potential rates of air conditioning with the people exposed to heat stress based on projections of climate models, lets us calculate the cooling gap – the difference between people exposed to heat stress and people who can protect themselves against it with the use of air conditioning.

Depending on whether we find ourselves in the best- or the worst-case scenario of socioeconomic development could mean anywhere between two billion and five billion people globally unable to protect themselves against heat stress with air conditioning in 2050. This range only grows with longer time horizons, with Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia being the areas of the world where these differences are the starkest.

We hope that our paper will motivate further investigations of potential gaps in adaptation that point to insufficient adaptive capacity and help to identify the areas and populations most at risk, as well as what additional work needs to be done in terms of socioeconomic improvements before we can reasonably expect adaptation to take place. Our findings on the importance of factors beyond just GDP, suggest that helping communities to build their adaptive capacity doesn’t mean only throwing money at them (although that would make for a decent start!), but international efforts must focus on issues such as eradicating inequalities, supporting smart urban development, strengthening institutions, and providing education.

So, let’s not take it for granted that we will all be able to adapt either now or in the future. Eliminating the causes of climate change must remain the number one policy objective that will help to reduce the need for adaptation in the first place. But number two could be helping communities that have no option but to cope with what’s already coming at them. Highlighting in our research what the implications of different adaptive capacities are for preservation of livelihoods, is a small step towards achieving this.

Reference:

Andrijevic, M., Byers, E., Mastrucci, A., Smits, J., & Fuss, S. (2021). Future cooling gap in shared socioeconomic pathways. Environmental Research Letters 16 (9) e094053. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/17411]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 18, 2021 | Austria, Climate, Climate Change, Communication, Education, Health

By Thomas Schinko, Acting Research Group Leader, Equity and Justice Research Group

Thomas Schinko introduces an innovative and transdisciplinary peer-to-peer training program.

What do we want – climate justice! When do we want it – now! The recent emergence of youth-led, social climate movements like #FridaysForFuture (#FFF), the Sunrise Movement, and Extinction Rebellion has reemphasized that at the heart of many – if not all – grand global challenges of our time, lie aspects of social and environmental justice. With a novel peer-to-peer education format, embedded in a transdisciplinary research project, the Austrian climate change research community responds to the call that unites these otherwise diverse movements: “Listen to the Science!”

The climate crisis raises several issues of justice, which include (but are not limited to) the following dimensions: First, intragenerational climate justice addresses the fair distribution of costs and benefits associated with climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as the rectification of damage caused by residual climate change impacts between present generations. Second, intergenerational justice focuses on the distribution of benefits and costs from climate change between present and future generations. Third, procedural justice asks for fair processes, namely that institutions allow all interested and affected actors to advance their claims while co-creating a low-carbon future. Movements like #FFF maneuver at the intersection of those three forms of climate justice when calling on policy- and decision makers to urgently take climate action, since “there is no planet B”.

Along with the emergence of these youth-led social climate movements came an increasing demand for the expertise of scientists working in the fields of climate change and sustainability research. To support #FFF’s claims with the best available scientific evidence, a group of German, Austrian, and Swiss scientists came together in early 2019 as Scientists for Future. Since then, requests from students, teachers, and policy and decision makers for researchers to engage with the younger generation have soared, also in Austria. Individual researchers like me have not been able to respond to all these requests at the extent we would have liked to.

In this situation of high demand for scientific support, the Climate Change Center Austria (CCCA) and The Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research (BMBWF) have put their heads together and established a transdisciplinary research project – makingAchange. By engaging early on with our potential end users – Austrian school students – a truly transdisciplinary team of researchers as well as practitioners in youth participation and education (the association “Welt der Kinder”) has co-developed this novel peer-to-peer curriculum. The training program, which runs over a full school year, sets out to provide the students not only with solid scientific facts but also with soft skills that are needed for passing on this knowledge and for building up their own climate initiatives in their schools and municipalities. One of the key aims is to provide solid scientific support while not overburdening the younger generation who often tend to put too high demands on themselves.

Establishing scientific facts about climate change and offering scientific projections of future change on its own does not drive political and societal change. Truly inter- and transdisciplinary research is needed to support the complex transformation towards a sustainable society and the integration of novel, bottom-up civil society initiatives with top-down policy- and decision making. Engaging multiple actors with their alternative problem frames and aspirations for sustainable futures is now recognized as essential for effective governance processes, and ultimately for robust policy implementation.

Also, in the context of makingAchange it is not sufficient to communicate science to students in order to generate real-world impact in terms of leading our societies onto low-carbon development pathways. What is additionally needed, is to provide them with complementary personal and social skills for enhancing their perceived self-efficacy and response efficacy, which is crucial for eventually translating their knowledge into real climate action in their respective spheres of influence.

Recent insights from a medical health assessment of the COVID-19 related lockdowns on childhood mental health in the UK have shown that we are engaging in an already highly fragile environment. In addition, a recent representative study for Austria has shown that the pandemic is becoming a psychological burden. The study authors are particularly concerned about young people; more than half of young Austrians are already showing symptoms of depression. Hence, we must engage very carefully with the makingAchange students when discussing the drivers and potential impacts of the climate crises. Particularly since some of them are quite well informed about research, which has shown (by using a statistical approach) that our chances of achieving the 1.5 to 2°C target stipulated in the Paris Agreement are now probably lower than 5%. Another example of such alarming research insights comes in the form of a 2020 report by the World Meteorological Organization, which warns that there is a 24% chance that global average temperatures could already surpass the 1.5°C mark in the next five years.

Zoom group picture taken at the end of the second online makingAchange workshop for Austrian school students. Copyright: makingAchange

The first makingAchange activities and workshops have now taken place – due to the COVID-19 regulations in an online format, which added further complexity to this transdisciplinary research project. Nevertheless, we were able to discuss some of the hot topics that the young people were curious about, such as the natural science foundations of the climate crisis, climate justice, or a healthy and sustainable diet. At the same time, we provided our students with skills to further transmit this knowledge and to take climate action in their everyday live – such as a climate friendly Christmas celebration in 2020. The school student’s lively engagement in these sessions as well as the overall positive (anonymous) feedback has proven that we are on the right track.

The role of science is changing fast from “advisor” to “partner” in civil society, policymaking, and decision making. By doing so, scientists can play an important, active role in implementing the desperately needed social-ecological transformation of our society without becoming policy prescriptive. With the makingAchange project, we are actively engaging in this transformational process – currently only in Austria but with high ambitions to scale-out this novel peer-to-peer format to other geographical and cultural contexts.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 20, 2020 | Climate, Energy & Climate, Women in Science, Young Scientists

By Chibulu Luo, PhD student at the University of Toronto (Civil Engineering) and 2016 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant.

Luo’s recent publication in the Journal of Cleaner Production considers the needs of the poorest and most vulnerable communities when exploring policy insights for Dar es Salaam’s energy transition.

Global discourse on sustainability rarely focuses on the Africa region as a key player in the global transition towards a cleaner low-carbon energy future. Filling this critical gap in the research is what has stimulated my doctoral studies.

Dar es Salaam © Timwege | Dreamstime

According to a recent report from the International Energy Agency, the Africa region contributed only 3.7% towards global energy-related GHG emissions in 2018, which perhaps explains why the region has remained largely ignored in current research on energy. However, with colleagues at the University of Toronto and Ontario Tech University, I assert that the growth of large cities such as Dar es Salaam should be critically considered in global efforts on climate change mitigation. My recently published paper estimates to the year 2050, the potential changes in residential energy use and GHG emissions in Dar es Salaam, among Africa’s most populous and fastest-growing cities. Like many African cities,contributes little to global GHG emissions; however, our paper projects a substantial increase in future emissions by the year 2050 – up to 4 to 24 times– which is quite overwhelming. According to our findings, this jump in emissions is due to a higher urban population in 2050 (expected to triple from 5 million in 2015, to as much as 16 million in 2050), and increased energy access and electricity consumption.

In developing these future estimates, we used the Shared-Socio-Economic Pathways (SSPs), developed by IIASA researchers, as a guiding narrative. While there may be some uncertainties with projecting GHG emissions pathways several years into the future, our findings could derive insights to the emissions pathways of other large African cities, and the critical role that these cities can play in global efforts to achieve the 1.5-degree, or even, 2-degree global warming target.

© Chibulu Luo

I first heard about the SSPs as a participant in the IIASA YSSP in 2016; this period was a tremendous time of growth and reflection in terms of my research direction. The opportunity to work amongst such a talented group of scientists in a collaborative environment and on issues that are globally relevant was an unforgettable experience. I especially enjoyed working with colleagues in the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program, where some of my early research ideas were formulated. At that time, I focused largely on resilience measures for infrastructure development in African cities, including Dar es Salaam.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

More updates from IIASA alumni or information on the IIASA network may be found here.

Nov 27, 2019 | Climate, Climate Change, Communication, Environment, IIASA Network, Women in Science

Award-winning climate communicator Katharine Hayhoe, an atmospheric scientist, professor of political science at Texas Tech University, and director of the Climate Center, discusses the importance of effective science communication in overcoming barriers to public acceptance of climate change in a recent interview with Rachel Potter, IIASA communications officer.

© Chris.Soldt | Boston College.MTS.Photography

Q: Can you tell us a bit about your specific areas of research as a scientist?

I study what climate change means to people, in the places where we live: how it is affecting our water supply, our health, our air quality, the integrity of our infrastructure, and other human and natural systems. Often when people think about climate change they think about polar bears or people who are living on low-lying islands in the South Pacific. I bring climate change down from the global scale to the local level because when we understand that it is an ‘everything issue’, that’s when we understand that we need to act.

Q: You have been widely recognized as a remarkable communicator. What do you see as key to effective science communication?

I believe effective communication begins with connecting and identifying shared values, and ends with talking about solutions. With climate change, sometimes people are overt in their opposition by outright saying the science isn’t real. More often however, it is passive opposition where people feel the problem is too big and there is nothing they can do to fix it. We need to present people with solutions that are practical and viable – in other words, actions that they can engage in.

Q: Why is science communication important?

Science communication explains how the world works. Today we are conducting an unprecedented experiment with our planet, the only one we have. Understanding this is one of the most important things anyone can do as a human being living on Earth.

Q: Can you briefly outline what you see as trends in public and political opinion with regard to human-induced climate change?

Our world is becoming increasingly polarized and we are dividing into tribes. It is happening with many issues and in many places around the world. When the world is changing so quickly, many of us feel uncomfortable with the rate of change, so we retreat to a more tribalized, divided society where we feel comfortable. But by doing so, we focus on the tiny fraction of what divides us rather than the vast preponderance of what unites us, because it makes us feel more secure to do so.

Climate change is a casualty of this fracturing, tribalism, and polarization that is happening – most notably in the US because there are only two political parties, so the tribalization there is much more obvious. In the US, the best predictor of whether people agree with the facts that: climate is changing, humans are responsible, and the impacts are serious, is not how much they know about science, it’s simply where they fall on the political spectrum. This politicization of science is also happening in the UK, Austria, across Europe, Canada, Australia, and Brazil.

© IIASA Katherine Hayhoe with members of the IIASA Women in Science Club

Q: How can this polarization and the barriers to dealing with climate change be challenged?

Climate change is a human issue – it doesn’t care if we are liberal or conservative, rich or poor, although the poor are being more affected than the rich. It affects all of us and almost everything we care about. For that reason, we must emphasize what unites us rather than what divides us. We need to challenge the idea that the solutions to climate change pose a bigger threat to our wellbeing, our comfort, the quality of our lives, our identity and who we are, than the impacts.

We must expose the myths that underlie inaction around climate change and examine them in an objective way. Will it really ruin our economy to fix climate change? Will it take us back to the Stone Age? If we don’t tackle the myths directly, they will continue to thrive in our sub-conscious. For example, in Canada there is an idea that a carbon tax will destroy the economy. I like to point out that there were four provinces in Canada that had a price on carbon before it became a federal policy, and those four provinces have led the country in terms of economic growth and output.

Q: What part do you see IIASA playing in being able to build bridges between countries across political divides?

IIASA stands in a key position at a pivotal time. It is a truly international organization in terms of its mandate, structure, governance, and the people that work here. Climate change is a global problem and IIASA is a global institution that can offer both big-picture and regionally-specific insights into climate impacts and solutions.

Katharine Hayhoe visited IIASA on 4 October 2019 to give a lecture titled, Barriers to Public Acceptance of Climate Science, Impacts, and Solutions, to IIASA researchers and to meet with the IIASA Women in Science Club. IIASA has a worldwide network of collaborators who contribute to research by collecting, processing, and evaluating local and regional data that are integrated into IIASA models. The institute has 819 research partner institutions in member countries and works with research funders, academic institutions, policymakers, and individual researchers in national member organizations.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Nov 6, 2019 | Climate, Climate Change, Health, Young Scientists

By Luiza Toledo, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2019

2019 YSSP participant Rory Gibb discusses his work at IIASA developing models to understand the effects of future land use, climate, and socioeconomic change on disease risk, focusing on Lassa fever in West Africa as a case study.

© Seth Doyle | Unsplash

Climate change is a fact and one of the most important environmental changes that populations will face in the coming decades. Changes in areas such as agriculture, energy, economics, and biodiversity, together with other natural and human-made health stressors, influence human health and disease in numerous ways. This is evident in the fact that the emergence and spread of many infectious diseases is on the rise, many of them transmitted from wildlife to humans – a trend that has been associated with the environmental changes we are currently experiencing. Warmer average temperatures can mean longer warm seasons, earlier spring seasons, shorter and milder winters, and hotter summers, during which the prevailing conditions may affect the population cycles of hosts, vectors (such as mosquitoes and ticks) and pathogens, thus increasing the incidence of certain vector-borne or zoonotic diseases. Changes to land use, such as expansion of agriculture, can impact ecological communities and bring people into greater contact with wildlife, again potentially facilitating the spread of pathogens.

Rory Gibb, a 2019 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant, is doing research to understand how global environmental changes – and in particular interactions between land use and climate change – affect zoonotic (animal-borne) infectious diseases. He applied for the YSSP this summer because of the institute’s research portfolio in different dimensions of human wellbeing, including poverty and inequality, food security, and water resilience. He hopes to contribute a dimension about infectious diseases.

©Liebentritt_Christoph | IIASA

Gibb is interested in understanding how the same kind of environmental pressures that affect biodiversity and ecosystems, such as agricultural expansion, intensification and urbanization, may also impact human health. He points out that even though many infectious diseases are widely studied, such as dengue fever and malaria, we still have a patchy understanding of the environmental factors driving many more neglected or recently emerging diseases – as is the case with Lassa fever, which occurs only in West Africa.

Lassa fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic illness recognized by global health institutions as an important rodent-borne disease, however, many important aspects of the disease’s ecology, epidemiology, and distribution remain poorly understood.

“We know that the spread of Lassa fever is very dependent on the environment, so it is sensitive to climate change, land use change, and other ecological changes, but we don’t have a very clear understanding of where it occurs and how many people are being affected every year,” Gibb explains.

Gibb aims to use current knowledge of the local ecological processes that drive the disease, including spatial modeling to determine the extent of the disease’s rodent reservoir host and its interactions with people, to develop a better understanding of the number of people infected with Lassa fever in West Africa. His YSSP project is focused on understanding how sensitive current patterns of disease risk may be to plausible future agricultural, climatic, and economic change in the region. To do this, he is projecting disease risk over large geographical areas using remotely sensed data on climate and landscape factors, and evaluating the effects of future socio-environmental scenarios on the predicted incidence of human disease. Ultimately, he is interested in how to develop better models to understand the relationship between environmental change and diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites that spread between humans and animals. He hopes that his research outcomes can help to guide disease surveillance efforts for policymakers.

“The spatial modeling work that I am doing will hopefully be useful in terms of giving some insight into regions of West Africa that are predicted to have a very high risk for Lassa fever, both now and under expected environmental changes, to assist in targeting public health interventions such as improving diagnostic test access. We can also identify important knowledge gaps, such as areas that are highly environmentally suitable for Lassa transmission, but in which the disease is apparently absent – these may be useful locations for intensified surveillance, or for showing that there are other ecological or epidemiological processes occurring that we are not accounting for.”

The impacts that environmental changes have on our health remind us how dependent we are on nature and how our own health depends on that of the environment. Environmental and human health cannot and should not be seen as two separate things.

“I want to do work that highlights the importance of understanding human dependence on nature and the necessity of understanding how we can preserve the health of both ecosystems and people,” Gibb concludes.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 31, 2019 | Climate, Risk and resilience

By Finn Laurien, research assistant at the IIASA Risk and Resilience (RISK) Program, and doctoral student at the Vienna University for Economics and Business.

A major challenge in understanding community flood resilience is the lack of an empirically validated measure of it. To plug this gap the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance (ZFRA) developed the Flood Resilience Measurement for Communities (FRMC). In the first phase of the Alliance we applied the FRMC tool in 118 communities in nine different countries. This is what we learnt from it.

What is the Flood Resilience Measurement for Communities?

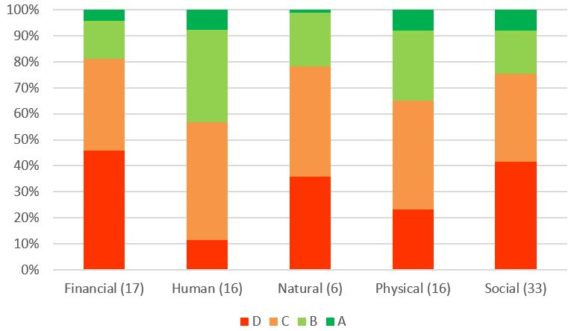

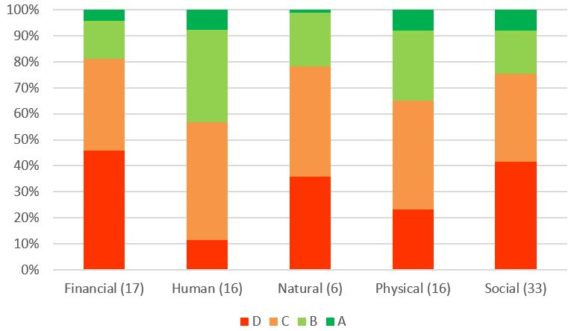

The FRMC approach holistically measures a set of “sources of resilience” before a flood happens (e.g. household savings or whether a community has a flood recovery plan) and looks at the post-flood impacts afterwards (e.g. level of loss and recovery time). The FRMC framework is built around the notion of five types of capital (the 5Cs: human, social, physical, natural, and financial capital) and the 4Rs of a resilient system (robustness, redundancy, resourcefulness, and rapidity). The data is collected and assessed via an integrated and hybrid platform. Each source of resilience is graded from A to D (best practice to significant below good standard) providing communities and decision-makers with an overview of the level of resilience capacity.

The 5 Capitals and 4 sources of resilience © Paulo Cerino

What did we learn from this large-scale analysis of community flood resilience?

Human and physical capital had the most sources assigned an A or B grade. The highest rated sources are education (value and equity), flood exposure perception, knowledge and awareness, communication, water, personal safety as well as health and sanitation. This could be a result of flood mitigation interventions traditionally being focused on building people’s skills and knowledge and/or physical structures.

Overview of frequency of grades for the sources of resilience by capital. Note: Number in bracket of capitals indicates the number sources in that capital. (Source: Campbell et al., 2019)

Despite the source-specific guidance and standardized data, grading is largely a judgment-based process and the FRMC includes a box where the assessor indicates how confident they are in the assigned grade. Since the trained assessors are practitioners with local understanding of the community the grades are influenced by their field expertise. The assessors were generally confident in the assigned grades and we found that their confidence increased the more data collection methods that were used.

Linking flood resilience and community characteristics

The FRMC was used in a range of different communities in developing and developed countries in contexts ranging from urban to rural and with some difference in past experience of flooding.

We discovered a correlation between poverty and lack of flood resilience and also found that having experienced very severe floods reduced a community’s level of resilience while experiencing frequent but less severe floods could help contribute to resilience, potentially by providing communities with relevant experience to adapt.

Does the FRMC process result in different interventions?

A key question we asked is whether the process of carrying out the baseline measurement and sharing results with the community resulted in interventions that were substantially different from what would have been implemented anyway. We find that it did, though to somewhat varying degrees.

Country teams overwhelmingly reported that the process helped them, their stakeholders, and communities to see flood resilience in a much more holistic way. For example, by broadening the perspective of flood resilience beyond that of physical infrastructure to also include social capital. The FRMC process influenced the implementation of a wide range of interventions, showing the breadth of the underlying conceptualization of resilience. The purpose of the FRMC approach is to help communities holistically strengthen their resilience and the broad range of interventions shows that this has worked.

Many country programs revised their project plans, log-frames and budgets as a result of the baseline measurement. Program staff highlighted how welcome it would be if other funders followed Zurich’s lead and allowed for similar in-depth analysis prior to intervention design and flexibility to act on the learning coming out of it to ensure the most effective intervention design.

What’s next for the FRMC?

This testing and data analysis has fed into the revision process for the development of the Next Generation FRMC which is currently being scaled to many more communities.

As the tool and measurement gets used in more communities and as part of more decision-making processes for flood resilient investments, we hope the usefulness and relevance of the tool will be demonstrated and adopted by many more organizations working to build community flood resilience.

Abel from Practical Action interviewing Consuelo, a community member in San Miguel de Viso, Peru as part of FRMC data collection ©Giorgio Madueño –

Reference:

Campbell KA, Laurien F, Czajkowski J, Keating A, Hochrainer-Stigler S, & Montgomery M (2019). First insights from the Flood Resilience Measurement Tool: A large-scale community flood resilience analysis. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 40: e101257. DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101257. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/16027/

Access available resources on the FRMC here.

This blog is reposted from a Flood Resilience Portal blog.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.