Apr 28, 2017 | Alumni, Systems Analysis, Young Scientists

University of Tokyo researcher Ali Kharrazi credits the 2012 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) with strengthening his passion, and giving him the research skills, to make a positive impact on humanity and sustainable development. He continues to collaborate with the institute as a guest researcher.

Ali Kharrazi

What is your research focus?

I’m currently examining both theoretical and empirical dimensions related to resilience and the wider application of sustainability indices and metrics. Towards this end, I have lately completed a literature review of empirical approaches to the concept of resilience, examined the resilience of global trade growth, and examined the resilience of water services within a river basin network.

My future project includes the examination of the application of modularity for resilience and its impact on other system characteristics of resilience, such as redundancy, diversity, and efficiency. In addition, I am collecting more data on the water-energy-food nexus, to empirically examine the resilience of these critical coupled human-environmental systems to various shocks and disruptions. I am working with other researchers towards channeling the emergence of urban big data towards practical research in sustainability indices and metrics, especially those which are related to resilience. Finally, I am engaged in what may be called ‘action research’ towards better teaching and engaging the concept of resilience to students.

How do you define resilience for a layperson or a student?

At its simplest, resilience is the ability of a system to survive and adapt in the wake of a disturbance.

The concept of resilience has been dealt by various disciplines: psychology, engineering, ecology, and network sciences. The literature on resilience relevant to coupled social-environmental systems therefore is very scattered, not approached quantitatively, and difficult to rely upon towards evidence based policy making. There are few empirical approaches to the concept of resilience. This makes it difficult to measure, quantify, communicate, and apply the concept to sustainability challenges.

In a recent study, Kharrazi explored the resilience of the Heihe river basin in China ©smiling_z | Shutterstock

What is missing from current approaches of studying resilience?

There is a need for more empirical advancements on the concept of resilience. Furthermore, empirical approaches need to be tested with real data and improved for their ability to measure and apply in policymaking. If you look at the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) the concept of resilience is used numerous times, however the indicators used to reflect the concept need to be improved to better reflect the elements of the concept of resilience. This includes the ability to consider adaptation, the ability to integrate social and environmental dimensions, and the ability to evaluate systems-level trade-offs.

We need to apply the different empirical approaches to the concept of resilience towards real-world sustainability challenges. With the emergence of big data, especially urban big data, we can better apply and improve these models.

How did you personally become interested in this field of research?

I always wanted to make a positive impact for humanity and our common interest in sustainable development. When I first started my PhD, my PhD supervisor at Tokyo University, Dr. Masaru Yarime, told me to always set your sight on the ‘vast blue ocean’ and how as researchers we should dedicate our time to critically important yet less researched areas. Given the global discussions of SDGs and the Agenda 2020 at that time I became interested in the concept of resilience, its relationship to common sustainability challenges, and our inability to measure and quantify this importance concept. My research stay at IIASA and YSSP and especially my experience with the ASA group strengthened my passion to contribute to this area and therefore since my PhD I have continued to research in this area and apply it to various domains, such as energy, water, and trade.

How would you say IIASA has influenced your career?

Without IIASA and especially the YSSP in the Advanced Systems Analysis program, my academic career would have never taken off. I am truly indebted to the YSSP, where I learned how to engage in scientific research with others from diverse academic and cultural backgrounds and most importantly had the chance to publish high quality research papers. IIASA also gave me the chance to get experience in applying for international competitive funding schemes and truly believe in the importance of science diplomacy and influence of science on global governance of common human-environmental problems in our modern world.

Follow Ali Kharrazi on Twitter

Ali Kharrazi, second from left, received his certificate with other participants of the 2012 YSSP

References

Kharrazi A, Akiyama T, Yu Y, & Li J (2016). Evaluating the evolution of the Heihe River basin using the ecological network analysis: Efficiency, resilience, and implications for water resource management policy. Science of the Total Environment 572: 688-696. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/13594/

Kharrazi A, Fath B, & Katzmair H (2016). Advancing Empirical Approaches to the Concept of Resilience: A Critical Examination of Panarchy, Ecological Information, and Statistical Evidence. Sustainability 8 (9): e935. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/13791/

Kharrazi A, Rovenskaya E, & Fath BD (2017). Network structure impacts global commodity trade growth and resilience. PLoS ONE 12 (2): e0171184. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/14385/

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 2, 2016 | Alumni, Young Scientists

By Muenire Koeseoglu, Young Scientists Summer Program alumnus.

In the summer of 2016 I traveled to Austria to take part in the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP). Being part of this intense experience, not only in terms of scientific research but also in a social and networking sense, was very rewarding. I learnt a lot, travelled a bit, and made many new international friends and valuable connections for life. However, if you are thinking about applying to the YSSP, some prior preparation and an open mind are essential to absorb what the environment offers.

My YSSP project examined water pollution issues in Scotland, looking into a trading framework that would help address diffuse pollution. My advice to any potential YSSPer working on applied topics like myself is to identify their research question in broad terms with room for possible change. Understand the policy landscape around the issue to establish the policy relevance, and possible partners in the field who might be willing collaborate as a part of their preparation before arriving to IIASA. Establishing connections might be time-consuming, and people might not necessarily be interested in taking the time to help a postgrad student or in sharing information or data which might be confidential, yet even a few successful attempts will be useful in terms of getting site-specific information, data, and feedback. It will also save you time during the YSSP and potentially help clarify the real-life problems beyond the literature or directives. For instance, my initial proposal for the YSSP was to design a trading scheme based on water allowances among different water users at catchment level. However, after relevant consultations, I realized that designing a scheme that would enable trading permits to pollute rather to take water would be more applicable to Britain and especially Scotland, where diffuse pollution impacts affects many more catchments than do water shortages.

2016 YSSP participants. © IIASA

From my perspective there were many things that made my YSSP a special experience but the most important factor has been the people, my YSSP peers, the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program (ASA) where I was based, and especially my supervisors. As a PhD student in the field of applied land economics, working with mathematicians (as my supervisors and most of my ASA colleagues were), was a very formative experience, as the world of mathematicians is very different to my career so far. Crucially, my supervisors taught me to deal with uncertainty not only in the data but also in the research structure and short-notice changes, and to realise the wider applications and possible extensions of the project rather than being trapped in details. After all, you can return to the details once you have made progress in your overall aims. Moreover, mathematicians are fast thinkers with a “can-do” attitude: a perfect combination for finding a solution in mathematical terms to the next practical problem you face.

I believe I have benefited a lot from this trans-disciplinary cooperation and look forward to working with people from different disciplines again, to learn from their perspectives and expertise.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 10, 2016 | Alumni, Demography, Young Scientists

by Julia M. Puaschunder, alumna of the IIASA Young Scientist Summer Program 2016.

The world is on the move. Currently, more than 250 million people live outside their countries of birth. Of the moving masses, an estimated 6% are refugees fleeing across borders to more favorable environments. The ongoing European refugee crisis has increased the pressure to reap the benefits from migration while alleviating the burdens of societal movement.

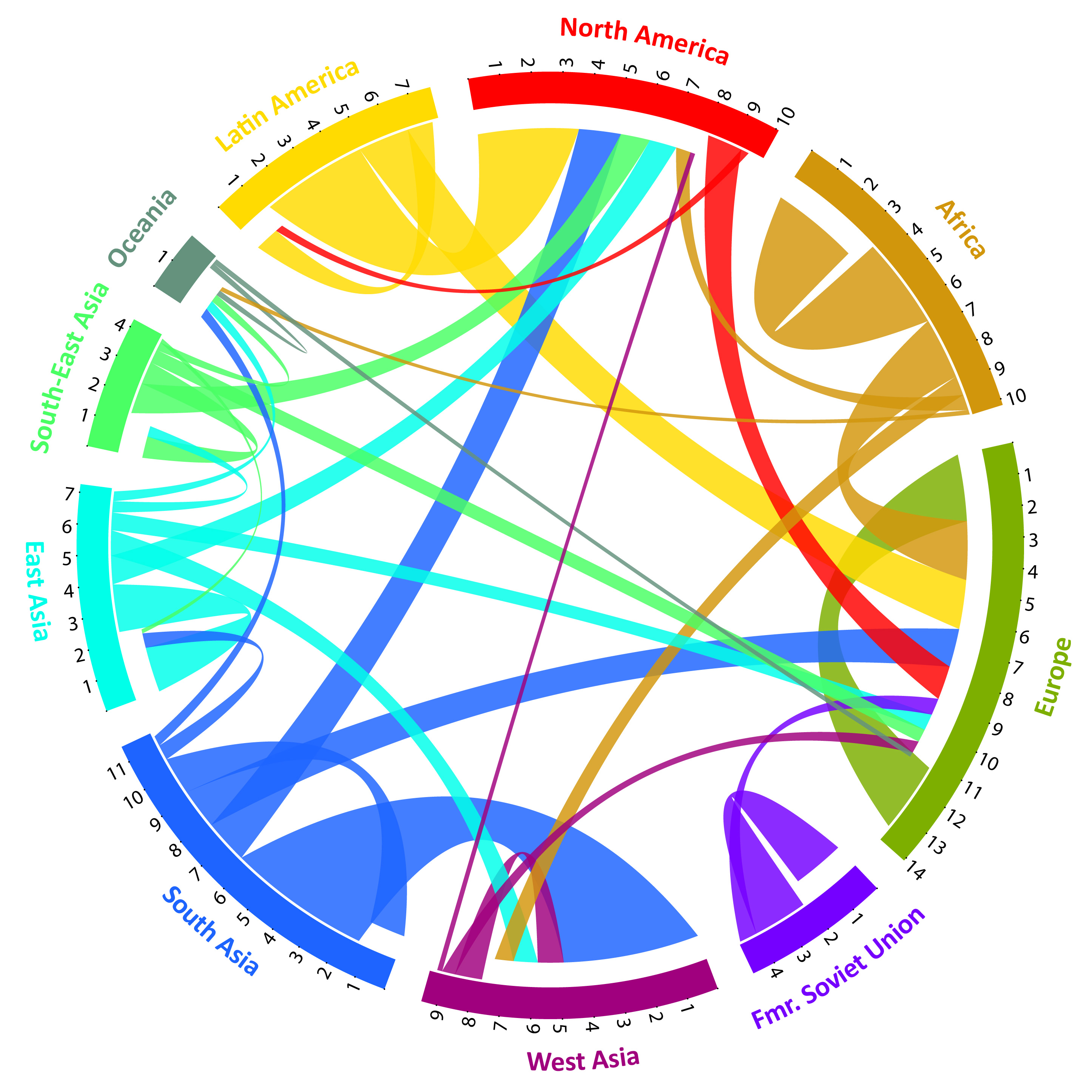

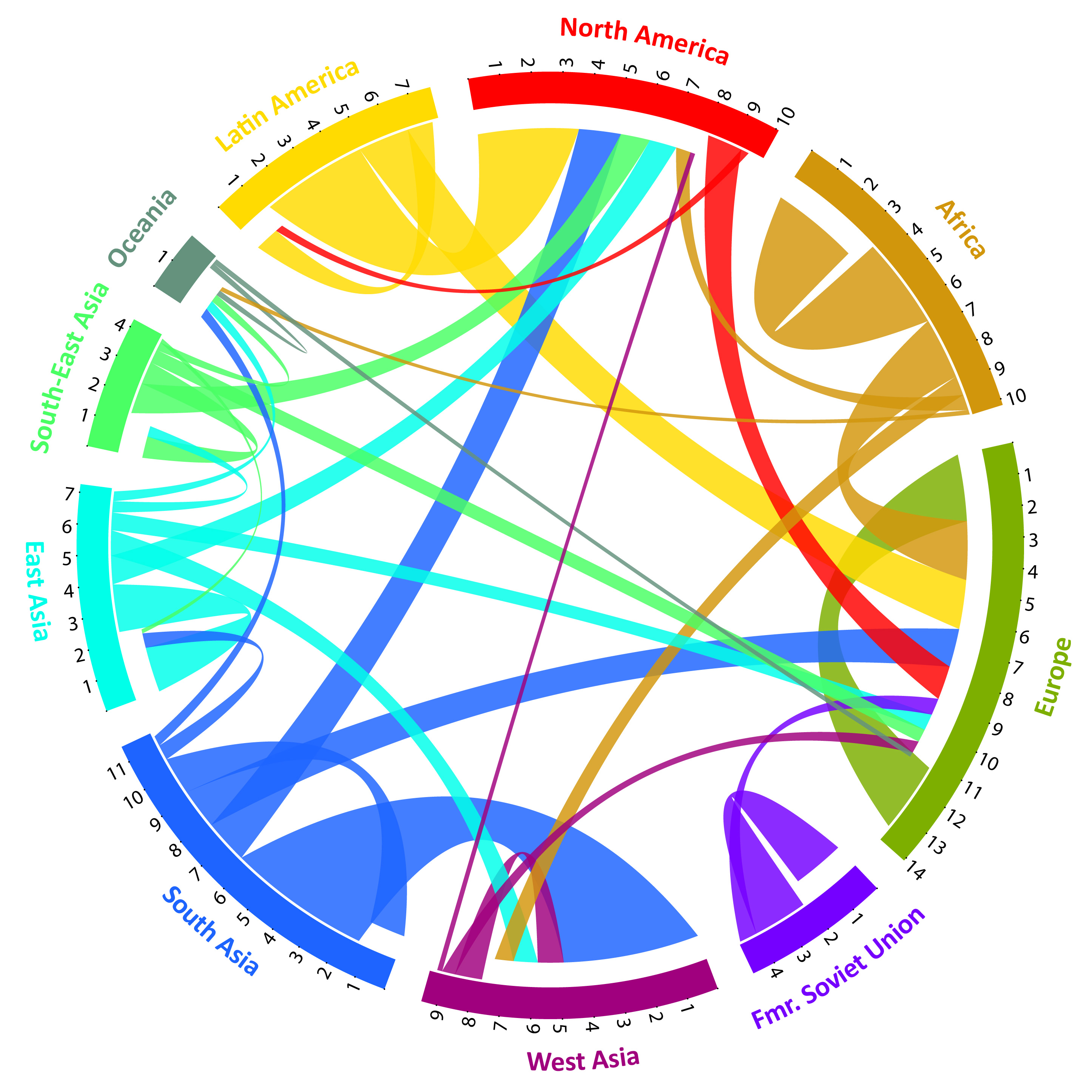

Estimates of directional flows between 123 countries between 2005-2010. Only flows containing at least 50,000 migrants are shown. “The Global Flow of People” (www.global-migration.info) is by Nikola Sander, Guy Abel & Ramon Bauer, and published in Science as “Quantifying global international migration flows” in 2014 (vol. 343: 1520-152).

Concerns were recently raised as to whether granting asylum to refugees—who often make up the most productive parts of their original populations—prevents (re)development in their fractionated home countries? An important consideration absent in these debates are the monetary gifts migrants send to their family members back home.

The World Bank estimates that migrants currently return around 450 billion US Dollars per year to the developing countries they came from, and this number is expected to rise. These monetary remittances have multiple positive impacts, including economic growth. As refugees are primarily younger to middle-aged, their remittances likely pay for their wives and children’s access to medical care and education, or support their parents when pension systems are missing.

Intergenerational monetary transfers are therefore the focus of my recent publication Gifts Without Borders. Contrary to conventional institutionalized sustainable development, remittances grounded in intergenerational care benefit from communication within families. Long-lasting family ties allow direct feedback. People truly care about their loved ones back home and families share their day-to-day experiences honestly. Intergenerational remittances beyond borders are thus a purer and potentially longer-enduring pathway to sustainable development, as these stable funding streams’ impact is more accountable than standard international aid.

Based on World Bank and OECD data covering almost all countries of the world, my forthcoming publication in the book ‘Intergenerational Responsibility in the 21st Century’ highlights that the intergenerational glue of a migrating population helps countries lacking socially responsible and future-oriented public sectors. Rather than blaming asylum-granting countries for removing the labor force from fragile territories, hosting refugees is portrayed as making use of human capital in stable economies, while refugees—at the same time—develop their former homelands by direct monetary contributions in a natural, transparent, and accountable way. In the age of migration, analyzing intergenerational networks and their financial flows is an important, but unexplored, facet of sustainable development. My findings open prospective research avenues on how we can align the economic outcomes of human capital mobility with sustainable development.

The IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program granted a vibrant setting to discuss my findings in a group of international, diverse, and multi-disciplinary future academic leaders during this summer, which was filled with beautiful moments in the historic Schloss Laxenburg in Austria. Recently IIASA also launched a Joint Research Centre of Expertise with the European Commission on Population and Migration, which aims to predict how migration will impact future economies and societies. In addition, the Advanced Systems Analysis (ASA) Program hosts the ‘Economic migration, capital flows, and welfare’ collaboration between ASA and the World Population Program to model dynamics of economic migration and investment. This research is also directly related to my New School Economic Review paper ‘Putty Capital and Clay Labor: Differing European Union Capital and Labor Freedom Speeds in Times of European Migration,’ which elucidates trade differences in capital and labor flows gravitating the benefits and burdens of globalization unequally and the potential problems arising for the European project from migration.

The Alpbach-Laxenburg Group Retreat 2016 on New Business Models for Sustainable Development. © Matthias Silveri | IIASA

Above all, attending the IIASA 2016 Alpbach-Laxenburg Group Retreat at the European Forum Alpbach helped to enhance my understanding of the relationship between migration and intergenerational responsibility. All these endeavors are targeted at contributing to sustainable development in a world on the move.

More information on the author of the post: www.juliampuaschunder.com

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 6, 2016 | Alumni, Systems Analysis

Chibulu Luo, PhD Student in the Department of Civil Engineering at the University of Toronto, and a 2016 participant in the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program

We cannot think about sustainable development without having a clear agenda for cities. So, for the first time, the world has agreed – under the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the New Urban Agenda – to promote more sustainable, resilient, and inclusive cities. Achieving this ambitious target is highly relevant in the context of African cities, where most future urban growth will occur. But it is also a major challenge.

Of the projected 2.4 billion people expected to be added to the global urban population between now and 2050, over half (1.3 billion) will be in Africa. The continent’s urban communities will experience dramatic shifts in living and place significant pressure on built infrastructure and supporting ecosystem services. As many cities are yet to be fully developed, newly built infrastructure (estimated to cost an additional US$30 to $100 billion per year) will impact their urban form (i.e. the configuration of buildings and open spaces) and future land use.

In order to realize the SDGs, African cities, in particular, need an ecosystem-based spatial approach to urban planning that recognizes the role of nature and communities in enabling a more resilient urban form. In this regard, more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics between urban form and the social and ecological aspects of cities is critical.

Unfortunately, research to investigate these relationships in the context of African cities has been limited. That’s why, as a Young Scientist at IIASA, I sought to address these research priorities, by asking the following questions: What is the relationship between urban form and the social and ecological aspects of African cities? How has form been changing over time and what are the exhibiting emergent properties? And what factors are hindering a transition towards a more resilient urban form?

Fundamentally, my research approach applies a social-ecological system (SES) lens to investigate these dynamics, where resilience is defined as the capacity of urban form to cope under conditions of change and uncertainty, to be able to recover from shocks and stresses, and to retain basic function. At the same time, resilience is characterized by the interplay between the physical, social, and ecological performance of cities.

Resilient urban forms are spatially designed to support social and ecological diversity, such as preserving and managing urban greenery

Photo Credit: Image of Lusaka, Zambia, posted on #BeautifulLusaka Facebook Page

Currently, Africa’s urbanization is largely unplanned. Urban expansion has led to the destruction of natural resources and increased levels of pollution and related diseases. These challenges are further compounded by inadequate master plans – which often date back to the colonial era in many countries – and capacity to ensure equitable access to basic services, particularly for the poorest dwellers. Consequently, over 70% of people in urban areas live in informal settlements or slums.

My summer research focused on the specific case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Lusaka, Zambia – two cities with very different forms, and social and ecological settings. I used the SES approach to develop a more holistic understanding of the local dynamics in these cities and emerging patterns of growth. My findings show that urbanization has resulted in high rates of sprawl and slum growth, as well as reductions in green space and increasing built-up area. This has ultimately increased vulnerabilities to climate-related impacts such as flooding.

Densely built slum in Dar es Salaam due to unplanned urban development

Photo Credit: tcktcktck.org

Using satellite images in Google Earth Engine, I also mapped land cover and urban forms in both cities in 2005 and 2015 respectively, and quantitatively assessed changes during the 10-year period. Major changes such as the rapid densification of slum areas are considered to be emergent properties of the complex dynamics ascribed by the SES framework. Also, urban communities are playing a significant role in shaping the form of cities in an informal manner, and are not often engaged in the planning process.

Approaches to address these challenges have been varied. On the one hand, initiatives such as the Future Resilience for African Cities and Lands (FRACTAL) project in Lusaka are working to address urban climate vulnerabilities and risks in cities, and integrate this scientific knowledge into decision-making processes. One the other hand, international property developers and firms are offering “new visions for African cities” based on common ideas of “smart” or “eco“ cities. However, these visions are often incongruous with local contexts, and grounded on limited understanding of the underlying local dynamics shaping cities.

My research offers starting point to frame the understanding of these complex dynamics, and ultimately support more realistic approaches to urban planning and governance on the continent.

References

Cobbinah, P. B., & Darkwah, R. M. (2016). African Urbanism: the Geography of Urban Greenery. Urban Forum.

IPCC (b). (2014). Working Group II, Chapter 22: Africa. IPCC.

LSE Cities. (2013). Evolving Cities: Exploring the relations between urban form resilience and the governance of urban form. London School of Economics and Political Science.

OECD. (2016). African Economic Outlook 2016 Sustainable Cities and Structural Transformation. OECD.

The Global Urbanist. (2013, November 26). Who will plan Africa’s cities? Changing the way urban planning is taught in African universities.

UNDESA. (2015). Global Urbanization Prospects (Key Findings).

Watson, V. (2013). African urban fantasies: dreams or nightmares. Environment & Urbanization.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 15, 2016 | Alumni, Climate, Climate Change, Young Scientists

César Terrer, participant in the IIASA 2016 Young Scientists Summer Program, and PhD student at Imperial College London, recently made a groundbreaking contribution to the way scientists think about climate change and the CO2 fertilization effect. In this interview he discusses his research, his first publication in Science, and his summer project at IIASA.

Conducted and edited by Anneke Brand, IIASA science communication intern 2016.

César Terrer ©Vilma Sandström

How did your scientific career evolve into climate change and ecosystem ecology?

I studied environmental science in Spain and then I went to Australia, where I started working on free-air CO2 enrichment, or FACE experiments. These are very fancy experiments where you fumigate a forest with CO2 to see if the trees grow faster. In 2014 I moved to London for my PhD project. There, instead of focusing on one single FACE experiment, I collected data from all of them. This allowed me to make general conclusions on a global scale rather than a single forest.

You recently published a paper in Science magazine. Could you summarize the main findings?

We found that we can predict how much CO2 plants transfer into growth through the CO2 fertilization effect, based on two variables—nitrogen availability and the type of mycorrhizal, or fungal, association that the plants have. The impact of the type of mycorrhizae has never been tested on a global scale—and we found that it is huge. I think it’s fascinating that such tiny organisms play such a big role at a global scale on something as important as the terrestrial capacity of CO2 uptake.

How did you come up with the idea? One random day in the shower?

Long story short, researchers used to think that plants will grow faster, and take up a lot of the CO2 we emit. They assumed this in most of their models as well. But plants need other elements to grow besides CO2. In particular, they need nitrogen. So scientists started to question whether the modeled predictions overestimated the CO2 fertilization effect, because the models did not consider nitrogen limitation. To find out, I analyzed all the FACE experiments and indeed I saw that in general plants were not able to grow faster under elevated CO2 and nitrogen limitation. However, in some cases plants were able to take advantage of elevated CO2 even under nitrogen limitation. I grouped together the experiments where plants could grow under nitrogen limitation and after a lot of reading I saw what they had in common: the type of fungi! It turned out that one type of mycorrhizae is really good at transferring large quantities of nitrogen to the plant and the other type is not.

How did that feel?

Awesome! When I saw the graph, I knew: this is going to be important. Of course, after this, my coauthors helped me to polish the story. Without them, the conclusions would not be as robust and clear.

So how does this process work? Where do the fungi get the nitrogen from?

Particular soils might have a lot of nitrogen, but the amount available for plants to absorb might be low. Also, plants have to compete with non-fungal microorganisms for nitrogen. So if there is not much there, the microorganisms take it all. It’s called immobilization. Instead of mineralizing nitrogen, they immobilize it so that plants cannot take it up, at least not in the short term. Some types of fungi are much more efficient in accessing nitrogen, and associated with roots they allow plants to overcome limitations.

Nitrogen mobilization abilities of different types of fungi. Growth of plants associated with fungi not beneficial for nitrogen uptake (illustrated as grass roots on the left) could be limited by low nitrogen availability in soil. Other plants have the advantage of increased nitrogen uptake due to their beneficial association with certain types of fungi (illustrated as yellow mushrooms connected to the roots of the tree on the right). ©Victor O. Leshyk.

What is the impact of your findings?

Plants currently take up 25-30% of the CO2 we emit, but the question is whether they will be able to continue to do so in the long term. Our findings bring good and bad news. On the one hand, the CO2 fertilization effect will not be limited entirely by nitrogen, because some of the plants will be able to overcome nitrogen limitation through their root fungi. But on the other hand, some plant species will not be able to overcome nitrogen limitation.

There was a big debate about this. One group of scientists believed that plants will continue to take up CO2 and the other group said that plants will be limited by nitrogen availability. These were two very contrasting hypotheses. We discovered that neither of the hypotheses was completely right, but both were partly true, depending on the type of fungi. Our results could bring closure to this debate. We can now make more accurate predictions about global warming.

What will you do at IIASA and how will you link it to your PhD?

I want to upscale and quantify how much carbon plants will take up in the future. If we are to predict the capacity of plants to absorb CO2, we need to quantify mycorrhizal distribution and nitrogen availability on a global scale. We are updating mycorrhizal distribution maps according to distribution of plant species. We know for instance that pines are associated with ectomycorrhizal fungi and always will be. To quantify nitrogen availability we use maps of different soil parameters that are available on a rough global scale.

© Adam Edwards | Dreamstime.com

About César Terrer

Prior to his PhD, Terrer studied at the University of Murcia in Spain and the University of Western Sydney in Australia.

Currently he is a member of the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London, UK. For this study he collaborated with researchers from the University of Antwerp, Northern Arizona University, Indiana University and Macquarie University.

In the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program, Terrer works together with Oskar Franklin from the Ecosystem Services and Management Program and Christina Kaiser from the Evolution and Ecology Program.

Further reading

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 18, 2016 | Alumni, Systems Analysis, Young Scientists

By Célian Colon, PhD student at the Ecole Polytechnique in France & IIASA Mikhalevich award winner

How can we best tackle risks in our complex and interconnected economies? With globalization and information technologies, people and processes are increasingly interdependent. Great ideas and innovations can spread like wildfire. However, so can turbulence and crises. The propagation of risks is a key concern for policymakers and business leaders. Take the example of production disruption: with global supply chains, local disasters or man-made accidents can propagate from one place to another, and generate significant impact. How can this be prevented?

Risk propagation is like a domino effect. Credit: Martin Fisch (cc) via Flickr

As part of my PhD research, I met professionals on the ground and realized that supply risk propagation is a particularly tricky issue, since most parts of the chains are out of their control. Supply chains can be very long, and change with time. It is difficult to keep track of who is working with whom, and who is exposed to which hazard. How then can individual decisions mitigate systemic risks? This question directly connects to the deep nature of systemic problems: everyone is in the same boat, shaping it and interacting with each other, but no one is individually able to steer it. Surprising phenomena can emerge from such interactions, wonderfully illustrated by bird flocking and fish schooling.

As an applied mathematician thrilled by such complexities, I was enthusiastic to work on this question. I built a model where firms produce and interact through supply chain relationships. Pen and paper analyses helped me understand how a few firms could optimally react to disruptions. But to study the behavior of truly complex chains, I needed the calculation power of computers. I programmed networks involving a large number of firms, and I analyzed how localized failures spread throughout these networks, and generate aggregate losses. Given the supply strategy adopted by each firm, how could systemic risk be mitigated?

With my collaborators at IIASA, Åke Brännström, Elena Rovenskaya, and Ulf Dieckmann, we have highlighted the key role of coordination in managing risks. Each individual firm affects how risks propagate along the chain. If they all solely focus on maximizing their own profit, significant amounts of risk remain. But if they cooperate, and take into account the impact of their decisions on the risk profile of their trade partners, risk can be effectively mitigated. Reducing systemic risks can thus be seen as a common good: costs are heterogeneously borne by firms while benefits are shared. Interestingly, even in long supply chains, most systemic risks can be mitigated if firms only cooperate with only one or two partners. By facilitating coordination along critical supply chains, policy-makers can therefore contribute to the reduction of risk propagation.

Colon’s model analyzes how firms produce and interact through supply chain relationships. Credit: Jan Buchholtz (cc) via Flickr

Drawing robust conclusions from such models is a real challenge. On this matter, I benefited from the experience of my IIASA supervisors. Their scientific intuitions greatly helped me focusing on the most fertile ground. It was particularly exciting to borrow techniques from evolutionary ecology and apply them to an economic context. Conceptually, how economic agents co-adapt and influence each other shares many similarities with the co-evolution of individuals in an ecological environment. To address such complex issues, I strongly believe in the plurality of approaches: by illuminating a problem from different angles, we can hope to see it more clearly!

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.