May 2, 2018 | Alumni, Economics, IIASA Network, Science and Policy

W. Brian Arthur from the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), and a former IIASA researcher, talks about increasing returns and the magic formula to get really great science.

Recently, Brian stopped in at the Complexity Science Hub Vienna, of which IIASA is a member institution, and spoke to Verena Ahne about his work.

Brian Arthur (© Complexity Science Hub)

Brian, now 71, is one of the most influential early thinkers of the SFI, a place that without exaggeration could be called the cradle of complexity science.

Brian became famous with his theory of increasing returns. An idea that has been developed in Vienna, by the way, where Brian was part of a theoretical group at the IIASA in the early days of his career: from 1978 to 1982.

“I was very lucky,” he recalls. “I was allowed to work on what I wanted, so I worked on increasing returns.”

The paper he wrote at that time introduced the concept of positive feedbacks into economy.

The concept of “increasing returns”

Increasing returns are the tendency for that which is ahead to get further ahead, for that which loses advantage to lose further advantage. They are mechanisms of positive feedback that operate—within markets, businesses, and industries—to reinforce that which gains success or aggravate that which suffers loss. Increasing returns generate not equilibrium but instability: If a product or a company or a technology—one of many competing in a market—gets ahead by chance or clever strategy, increasing returns can magnify this advantage, and the product or company or technology can go on to lock in the market.”

(W Brian Arthur, Harvard Business Review 1996)

This was a slap in the face of orthodox theories which saw–and some still see–economy in a state of equilibrium. “Kind of like a spiders web,” Brian explains me in our short conversation last Friday, “each part of the economy holding the others in an equalization of forces.”

The answer to heresy in science is that it does not get published. Brian’s article was turned down for six years. Today it counts more than 10.000 citations.

At the latest it was the development and triumphant advance of Silicon Valley’s tech firms that proved the concept true. “In fact, that’s now the way how Silicon Valley runs,” Brian says.

The youngest man on a Stanford chair

William Brian Arthur is Irish. He was born and raised in Belfast and first studied in England. But soon he moved to the US. After the PhD and his five years in Vienna he returned to California where he became the youngest chair holder in Stanford with 37 years.

Five years later he changed again – to Santa Fe, to an institute that had been set up around 1983 but had been quite quiet so far.

Q: From one of the most prestigious universities in the world to an unknown little place in the desert. Why did you do that?

A: In 1987 Kenneth Arrow, an economics Nobel Prize winner and mentor of mine, said to me at Stanford: We’re holding a small conference in September in a place in the Rockies, in Santa Fe, would you go?

When a Nobel Prize winner asks you such a question, you say yes of course. So I went to Santa Fe.

We were about ten scientists and ten economists at that conference, all chosen by Nobel Prize winners. We talked about the economy as an evolving complex system.

Veni, vidi, vici

Brian came – and stayed: The unorthodox ideas discussed at the meeting and the “wild” and free atmosphere of thinking at “the Institute”, as he calls the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), thrilled him right away.

In 1988 Brian dared to leave Stanford and started to set up the first research program at Santa Fe. Subject was the economy treated as a complex system.

Q: What was so special about SF?

A: The idea of complexity was quite new at that time. But people began to see certain patterns in all sorts of fields, whether it was chemistry or the economy or parts of physics, that interacting elements would together create these patterns…To investigate this in universities with their particular disciplines, with their fixed theories, fixed orthodoxies–where it is all fixed how to do things–turned out to be difficult.

Take the economy for example. Until then people thought it was in an equilibrium. And there we came and proved, no, economics is no equilibrium! The Stanford department would immediately say: You can’t do that! Don’t do that! Or they would consider you to be very eccentric…

So a bunch of senior fellows at Los Alamos in the 1980s thought it would be a good idea if there was an independent institute to research these common questions that came to be called complexity.

At Santa Fe you could talk about any science and any basic assumptions you wanted without anybody saying you couldn’t or shouldn’t do that.

Our group as the first there set a lot of this wild style of research. There were lots of discussions, lots of open questions, without particular disciplines… In the beginning there were no students, there was no teaching. It was all very free.

This wild style became more or less the pattern that has been followed ever since. I think the Hub is following this model too.

The magic formula for excellence

Q: Was this just a lucky concurrence: the right people and atmosphere at the right time? Or is there a pattern behind it that possibly could be repeated?

A: I am sure: If you want to do interdisciplinary science – which complexity is: It is a different way of looking at things! – you need an atmosphere where people aren’t reinforced into all the assumptions of the different disciplines.

This freedom is crucial to excellent science altogether. It worked out not only for Santa Fe. Take the Rand Corporation for instance, that invented a lot of things including the architecture of the internet, or the Bell Labs in the Fifties that invented the transistor. The Cavendish Lab in Cambridge is another one, with the DNA or nuclear astronomy…

The magic formula seems to be this:

- First get some first rate people. It must be absolutely top-notch people, maybe ten or twenty of them.

- Make sure they interact a lot.

- Allow them to do what they want – be confident that they will do something important.

- And then when you protect them and see that they are well funded, you are off and running.

Probably in seven cases out of ten that will not produce much. But quite a few times you will get something spectacular – game changing things like quantum theory or the internet.

Don’t choose programs, choose people

Q: This does not seem to be the way officials are funding science…

A: Yes, in many places you have officials telling people what they need to research. Or where people insist on performance and indices… especially in Europe, I have the impression, you have a tradition of funding science by insisting on all these things like indices and performance and publications or citation numbers. But that’s not a very good formula.

Excellence is not measurable by performance indicators. In fact that’s the opposite of doing science.

I notice at places where everybody emphasize all this they are not on the forefront. Maybe it works for standard science; and to get out the really bad science. But it doesn’t work if you want to push boundaries.

Many officials don’t understand that.

In Singapore the authorities once asked me: How did you decide on the research projects in Santa Fe? I said, I didn’t decide on the research projects. They repeated their question. I said again, I did not decide on the research projects. I only decided on people. I got absolutely first rate people, we discussed vaguely the direction we wanted things to be in, and they decided on their research projects.

That answer did not compute with them. They are the civil service, they are extraordinarily bright, they’ve got a lot of money. So they think they should decide what needs to be researched.

I should have told them – I regret I didn’t: This is fine if you want to find solutions for certain things, like getting the traffic running or fixing the health care system. Surely with taxpayer’s money you have to figure such things out. But you will never get great science with that. All you get is mediocrity.

Of course now they asked, how do we decide which people should be funded? And I said: “You don’t! Just allow top people to bring in top people. Give them funding and the task of being daring.”

Any other way of managing top science doesn’t seem to work.

I think the Hub could be such a place – all the ingredients are here. Just make sure to attract some more absolutely first rate people. If they are well funded the Hub will put itself on the map very quickly.

This interview was originally published on https://www.csh.ac.at/brian-arthurs-magic-formula-for-excellence/

Nov 21, 2017 | Alumni, Poverty & Equity, Young Scientists

By Nemi Vora, participant of the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) 2017 and PhD student at the University of Pittsburgh.

“Was it worth the flight?” asked my fellow alumna of the YSSP Karen Umansky, at the end of our first day of attending the World Science Forum in Jordan. The total journey from the USA to Jordan had taken 20 hours, layovers included. She was well aware of my travel anxiety, fear of immigration officials (an Indian passport doesn’t always make things easy), and fear of traveling alone on a militarized Dead Sea road at night (you can see the west bank on the other side). I had spammed her every day about it.

The IIASA delegation at the World Science Forum © IIASA

I didn’t have an answer; the panels I attended did not focus on anything new. We were all aware of issues: digitization without destruction, women in science, support for emerging scientists, meeting the sustainable development goals, and so on. However, every conference has a different key to unlock its potential and Jan Marco Müller, head of the IIASA directorate office and another recipient of my daily email spam, informed me that it was not the panels, but the corridor conversations that mattered here.

I soon found out that it was not just the corridors, but even the brief conversations in shuttles where the conference happened. I met a program manager for the US National Science Foundation who told me about research work on the food-energy-water nexus that they funded for the Nile, an area similar to my thesis. I met a regional director of UNESCO and a science minister from Colombia, who together set up new Africa-Latin America project partnerships during the shuttle ride.

One important part of each conversation was the significance of the place I was in, something I had previously missed completely. The ability of this small country, surrounded by conflict zones on each side, to arrange for such a large gathering of this kind, bringing together opponents and allies alike, and to take a stand for enabling peace through science, was remarkable.

True, the issues were not new, but the context was much more specific to the needs of a conflict-ridden world. For instance, discussing how to provide access to digital resources such as open data for policymaking or scientific journals for all the countries, promoting the achievements of Arab women scientists and those of the other developing regions amidst cultural and economic hardships, and fostering innovation in emerging scholars in the developing world where lack of resources was part of academic life.

Jordan also showcased the recently established SESAME facility: the Middle East’s first international science research center, a joint venture of a group of middle eastern countries, otherwise engaged in political conflicts. IIASA was representing a unique position here: originally founded as the bridge between East-West scientific collaboration during the Cold War, it served as an example, along with the fledgling SESAME, that geo-political boundaries did not hinder science and that such projects could be successful. Despite political tensions in individual countries, and having a passport that would not allow you to visit your colleague’s country, you could still work side-by side—a feat that SESAME scientists achieve every day.

As YSSPers, our goal was to talk about the benefits of global mentorship and how that could be leveraged to address the uneven distribution of resources. All of us came from different backgrounds: there was An Ha Truong from Vietnam, an energy economist studying optimization of biomass for coal power plants, there was Karen, the social scientist from Israel, studying emerging neo-Nazism in Europe, and then there was me—representing the USA and India as an environmental engineer.

Our co-panelists from the Berkeley Global Science Institute, also of diverse backgrounds, were engaged in setting up labs across the world, providing resources and mentorship to graduate students. While we had a lively session discussing our personal experiences, it wasn’t what we had to say but the session questions that struck a chord with us. The presence of conflicts add another layer of complexity to the already murky path of academia: how do you keep young scholars motivated to stay in the lab and work in a country threatened by war? How do you compete in cutting-edge science research when resources are scarce? How do you engage in public-private partnerships when your work may be more theoretical than applied?

The YSSPers taking part in a panel © IIASA

We need to collaborate more, provide access to the data and codes we use to carry out reproducible research, attempt to publish in open access platforms whenever feasible, and support our fellow scientists irrespective of their location or positions. This way, we would inch closer to solving some of these issues. Six months ago at IIASA, the HRH Sumaya bint El Hassan, co-chair of the World Science Forum, had asked me, “How do you eat an elephant?” Being a vegetarian, I couldn’t imagine ever eating one and I very naively told her so. On my way back from Jordan, with another long journey ahead of me, I realized the significance of her words: you eat it little by little.

Follow Nemi on twitter: @NemiVora

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 16, 2017 | Alumni, IIASA Network, Young Scientists

Lauren Hale, now professor of Family, Population and Preventive Medicine at the Stony Brook University School of Medicine talks about her time at the IIASA Young Scientist Summer Program in 1996, and her new role as part of the IIASA US National Member Organization.

©Lauren Hale

As a professor at Stony Brook University School of Medicine, I study how sleep is a mechanism through which policy and social factors can affect mental and physical health. I find that differences in sleep patterns across the population are contributing to disparities in health and wellbeing. My current study of nearly 1000 teens from across the USA seeks to understand the contributing factors (including school start times and screen-based media) of insufficient sleep and health concerns among the young. In addition, I serve on the board of directors of the National Sleep Foundation, and I’m the founding editor-in-chief of the academic journal, Sleep Health, which, ironically, has cut into my own sleep health.

Out of the thousands of colleges and universities in the USA where I could have ended up, it is a fortuitous coincidence that, just across the road, my initial IIASA mentor Warren Sanderson teaches in the Economics Department also at Stony Brook University. He still visits IIASA for three months every summer and continues to play a supportive role in my professional life.

I might never have pursued postgraduate work had it not been for my early experiences at IIASA. I had the unique opportunity to join IIASA for the Young Scientists Summer Program while still an undergraduate (long story). It was an incredible opportunity, as a college junior, to find myself within a week of my arrival in the summer of 1996, seated around a table with the world’s top demographers at an international workshop on world population projections. I credit Wolfgang Lutz for being so inclusive with the YSSPers. I found everything about systems dynamics and population modeling novel and exciting. For my summer project, I modeled the dynamics of tourism and fish populations off the coast of the Yucatan. Thankfully, I had enormous guidance and support from my mentor Warren Sanderson, and co-YSSPer Patricia Kandelaars. Patricia and I were both Aurelio Peccei scholars and invited back for a second summer, during which we pretended we were still in the YSSP program, joining for many heurigen evenings and other memorable weekend excursions.

Class of 1996 Young Scientists Summer Program © IIASA

Thanks to my positive experiences at IIASA, I entered a PhD program at Princeton University to pursue population studies, followed by a postdoctoral fellowship at the RAND Corporation, in Santa Monica, California. Although population sleep health research seems far afield from the interplay between fish and tourism in Mexico, I see a link to my experiences at IIASA, which is where I was introduced to systems thinking with policy relevance. Recently, I was honored to be invited to join the US National Member Organization for IIASA. Once again, I sought advice from Warren Sanderson, who encouraged me to accept the opportunity. I’m looking forward to giving back and reconnecting with IIASA.

Further info: Other YSSP stories.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 26, 2017 | Alumni, Climate Change, Poverty & Equity, Sustainable Development, Water, Young Scientists

Adil Najam is the inaugural dean of the Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University and former vice chancellor of Lahore University of Management Sciences, Pakistan. He talks to Science Communication Fellow Parul Tewari about his time as a participant of the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) and the global challenge of adaptation to climate change.

How has your experience as a YSSP fellow at IIASA impacted your career?

The most important thing my YSSP experience gave me was a real and deep appreciation for interdisciplinarity. The realization that the great challenges of our time lie at the intersection of multiple disciplines. And without a real respect for multiple disciplines we will simply not be able to act effectively on them.

Prof. Adil Najam speaking at the Deutsche Welle Building in Bonn, Germany in 2010 © Erich Habich I en.wikipedia

Recently at the 40th anniversary of the YSSP program you spoke about ‘The age of adaptation’. Globally there is still a lot more focus on mitigation. Why is this?

Living in the “Age of Adaption” does not mean that mitigation is no longer important. It is as, and more, important than ever. But now, we also have to contend with adaptation. Adaptation, after all, is the failure of mitigation. We got to the age of adaptation because we failed to mitigate enough or in time. The less we mitigate now and in the future, the more we will have to adapt, possibly at levels where adaptation may no longer even be possible. Adaption is nearly always more difficult than mitigation; and will ultimately be far more expensive. And at some level it could become impossible.

How do you think can adaptation be brought into the mainstream in environmental/climate change discourse?

Climate discussions are primarily held in the language of carbon. However, adaptation requires us to think outside “carbon management.” The “currency” of adaptation is multivaried: its disease, its poverty, its food, its ecosystems, and maybe most importantly, its water. In fact, I have argued that water is to adaptation, what carbon is to mitigation.

To honestly think about adaptation we will have to confront the fact that adaptation is fundamentally about development. This is unfamiliar—and sometimes uncomfortable—territory for many climate analysts. I do not believe that there is any way that we can honestly deal with the issue of climate adaptation without putting development, especially including issues of climate justice, squarely at the center of the climate debate.

COP 22 (Conference of Parties) was termed as the “COP of Action” where “financing” was one of the critical aspects of both mitigation and adaptation. However, there has not been much progress. Why is this?

Unfortunately, the climate negotiation exercise has become routine. While there are occasional moments of excitement, such as at Paris, the general negotiation process has become entirely predictable, even boring. We come together every year to repeat the same arguments to the same people and then arrive at the same conclusions. We make the same promises each year, knowing that we have little or no intention of keeping them. Maybe I am being too cynical. But I am convinced that if there is to be any ‘action,’ it will come from outside the COPs. From citizen action. From business innovation. From municipalities. And most importantly from future generations who are now condemned to live with the consequences of our decision not to act in time.

© Piyaset I Shutterstock

What is your greatest fear for our planet, in the near future, if we remain as indecisive in the climate negotiations as we are today?

My biggest fear is that we will—or maybe already have—become parochial in our approach to this global challenge. That by choosing not to act in time or at the scale needed, we have condemned some of the poorest communities in the world—the already marginalized and vulnerable—to pay for the sins of our climatic excess. The fear used to be that those who have contributed the least to the problem will end up facing the worst climatic impacts. That, unfortunately, is now the reality.

What message would you like to give to the current generation of YSSPers?

Be bold in the questions you ask and the answers you seek. Never allow yourself—or anyone else—to rein in your intellectual ambition. Now is the time to think big. Because the challenges we face are gigantic.

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 23, 2017 | Alumni, Water, Young Scientists

Firdos Khan Yousafzai, PhD student, University of Klagenfurt, Austria, and YSSP 2012 participant

In Pakistan, water supply fell from 5,260 cubic meters per capita in 1951 to 1,050 cubic meters per capita in 2010 according to the World Bank, and is likely to further fall in the future. According to the Falkenmark Water Stress Indicator, a country or a part of a country is said to experience “water stress” when the annual water supplies drop below 1,700 cubic meters per capita per year, and “water scarcity” if the annual water supplies drop below 1,000 cubic meters per capita per year. Water scarcity is especially critical for Pakistan because agriculture contributes 25% of the GDP and 36% of energy is obtained from hydropower.

In terms of geography, Pakistan is incredibly diverse, ranging from plain to desert, hills, forest, and plateaus from the Arabian Sea in the south and to the mountains of Karakorum in the north of the country. It has 796,096 square kilometers area—about the same size as Turkey–and approximately 200 million inhabitants.

The Karakorum mountains in northern Pakistan ©Piotr Snigorski | Shutterstock

Water availability is also different in different parts of the country. While various studies showed that climate change is happening all over Pakistan, research shows that the northern areas are more vulnerable. Possible reasons include the increasing population and deforestation, among others. Therefore, in my PhD work, which was also the subject of my work in the 2012 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program, I am investigating that how fast climate is changing and exploring its impacts on availability of water.

In a recent study we investigated this issue under four different climate change scenarios, from 2006 to 2039 in the future. Different scenarios have different assumptions about population growth, use of energy type, environmental protection, economic development, technological changes, etc. We calculated the changes on the basis of baseline and future time periods for climate and hydrological projections. We found an increasing trend in maximum and minimum temperature, while precipitation is also changing under each scenario.

To assess water availability and investigate the impacts of changing climate on the operation of reservoirs, we used Tarbela Reservoir as a measurement tool, developing hydrological projections for the reservoir under each scenario. Tarbela Dam is one of the biggest dams in the world, and has a storage capacity of approximately 7 million acre feet and the potential to produce 3,400 megawatts of electricity.

Cholistan Desert in southern Pakistan. Water scarcity varies widely throughout the geographically diverse country. ©image bird | Shutterstock

In our study, we considered all the relevant parameters related to water shortages and surpluses. To compare the status of water availability, we compared the baseline period and future time period. The results show an increasing trend in water availability, however, water scarcity is observed during some months under each scenario. Further, we also observed that there is a 23-40% increase in river flow under the considered scenarios while the average increase is approximately 35% during the future time period.

As a conclusion we can say that enough water is available in Pakistan, and will continue to be available in the future. Instead, the study confirms previous reports that the major problem is mismanagement.

The possible solution may include constructing more dams and storage capacity to store extra water during high river flow which then can be utilized during low river flow. This could probably also be helpful in flood control, raise the groundwater level, and provide cheap and clean electricity to national electricity grid—providing multiple benefits, in view of the fact that the country has faced ongoing energy crises for many years.

References

Ali S, Li D, Congbin F, Khan F (2015). Twenty first century climatic and hydrological changes over Upper Indus Basin of Himalayan region of Pakistan. Environmental Research Letters10 (2015) 014007. DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/10/1/014007.

Khan F, Pilz J, Ali S (2017). Improved hydrological projections and reservoir management in the Upper Indus Basin under the changing climate. Water and Environmental Journal. Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 235-244. DOI:10.1111/wej.12237.

Khan F, Pilz J, Amjad M, Wiberg D (2015). Climate variability and its impacts on water resources in the Upper Indus Basin under IPCC climate change scenarios. International Journal of Global Warming, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 46-69. DOI:10.1504/IJGW.2015.071583.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 9, 2017 | Alumni, Young Scientists

Former IIASA Director Roger Levien started the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) in the summer of 1977. After 40 years the program remains one of the institute’s most successful initiatives.

The idea for the YSSP came out of your own experience as a summer student at The RAND Corporation during your graduate studies. How did that experience inspire you to start the YSSP?

At RAND I was introduced to systems analysis and to working with colleagues from many different disciplines: mathematics, computer science, foreign policy, and economics. After that summer, I changed from a Master’s in Operations Research to a PhD program in Applied Mathematics and moved from MIT to Harvard, because I knew that I needed a broad doctorate to be a RAND systems analyst.

From that point on, I carried the knowledge that a summer experience at a ripe time in one’s life, as one is choosing their post university career, can be life transforming. It certainly was for me.

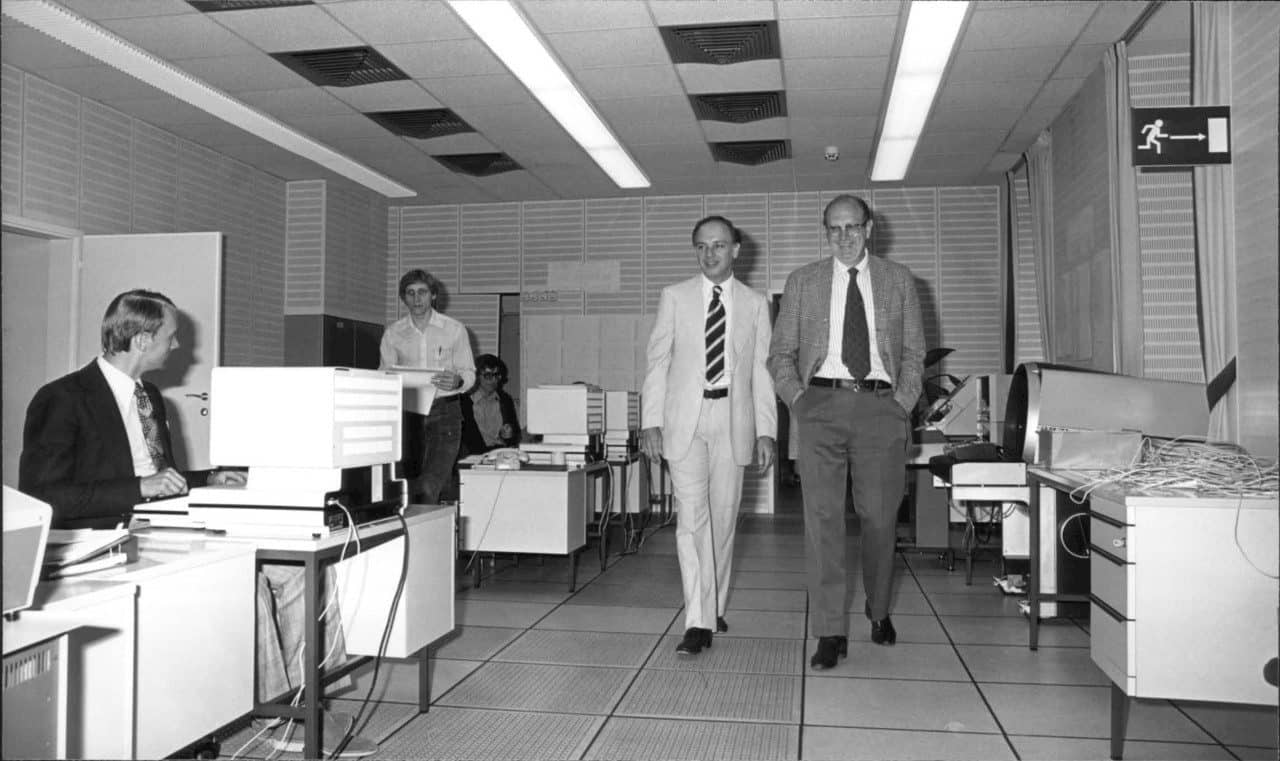

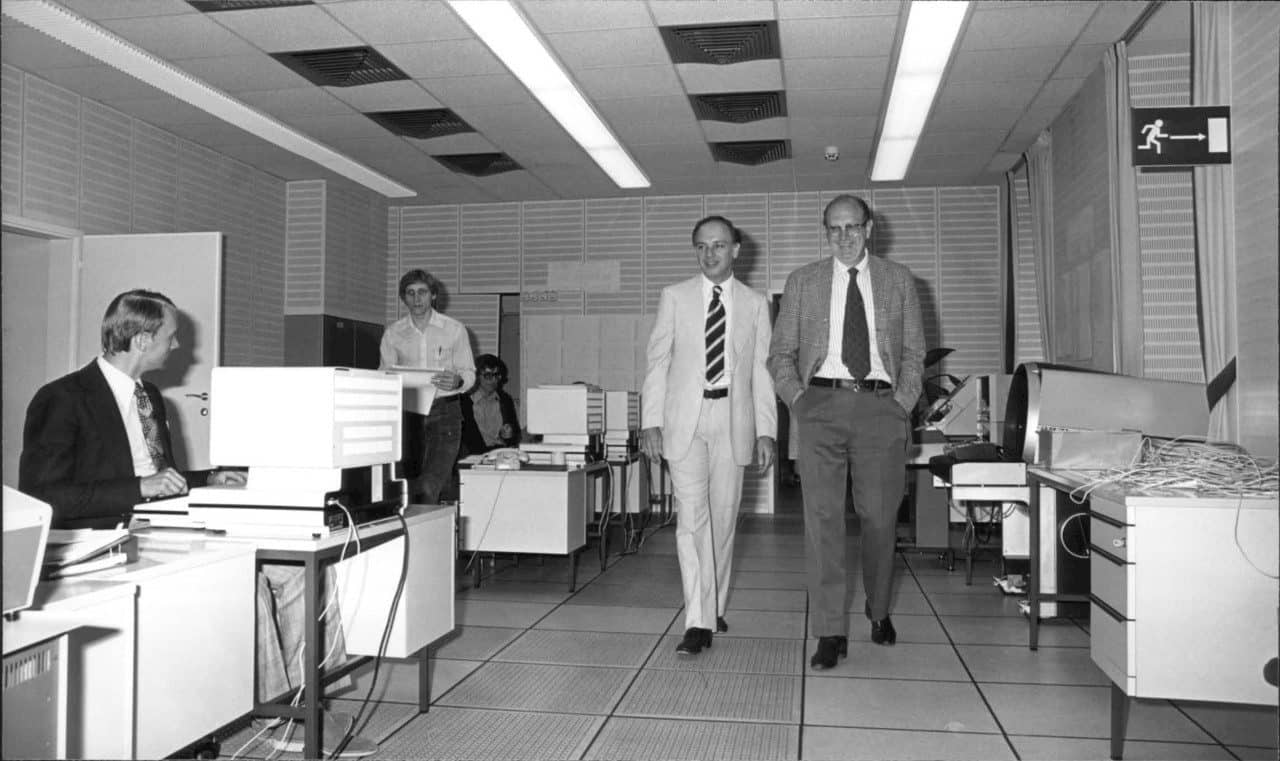

Roger Levien, left, with the first IIASA director Howard Raiffa, right. ©IIASA Archives

Why did you think IIASA would be a good place for such a summer program?

When I thought about such a program within the context of IIASA, it seemed to me that it would offer an even richer experience than mine at RAND. I thought, wouldn’t it be wonderful to bring young scientists from many nations together in their graduate-program years at IIASA. At that time, systems analysis was not well-known anywhere outside of the United States, and even there it was not very well known. In universities interdisciplinary research, and especially applied policy research, was almost nonexistent.

This would be an opportunity to introduce systems analysis to graduate students from around the world, who were otherwise deeply involved in a single discipline. It would be fruitful to bring them together to learn about the uses of scientific analysis to address policy issues, and about working both across disciplines and across nationalities.

What was your vision for the program?

I hoped that these students, who had been introduced to systems analysis at IIASA, would become an international network of analysts sharing a common understanding of international policy problems. And in the future, at international negotiations on issues of public policy, sitting behind the diplomats around the table would be technical experts, many of whom had been graduate students at IIASA, having worked on the same issue in a non-political international and interdisciplinary setting. At IIASA they would have developed a common language, a common way of thought, and perhaps working together at the negotiation they could use their shared view to help their seniors achieve success. A pipe dream perhaps, but also an ideal and a vision of what people from different countries and different disciplines who had studied the same problem with an international system analysis approach could accomplish.

Social activities have been an important component of the YSSP since the beginning ©IIASA Archives

The program is celebrating its 40th year. Why do you think it has been so successful?

I think there are many reasons for success. But for one thing, it’s my impression that just having 50 enthusiastic young scientists around brings an infusion of energy, which is a great boost to the institute. The young scientists also bring findings and methods on the cutting edges of their disciplines to IIASA.

What would be your advice to young scientists coming this summer for the 2017 program

It would be to engage as deeply as you can and as broadly as you can. This is an opportunity to learn about many things that aren’t on the curriculum of any university program. So, now’s the time to engage not only with other disciplines, but with people from other nations, to get their perspective. The people you meet this summer can be lifelong contacts. They can be your friends for life, your colleagues for life, and the opportunities that will open through them, though unpredictable, are bound to be invaluable, both professionally and personally.

This is a learning experience of an entirely different type from the typical graduate program, which goes deeper and deeper into a single discipline. You have a unique opportunity to go broader and wider, culturally, intellectually, and internationally.

IIASA will be celebrating the YSSP 40th Anniversary with an event for alumni on June 20-21, 2017.

This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.