By Jessie Jeanne Stinnett, Co-Artistic Director of Boston Dance Theater

I recently had the privilege of artistically collaborating on Dancing with the Future, a project spearheaded by Gloria Benedikt and Piotr Magnuszewski of IIASA with Martin Nowak of Harvard University. The process involved five dancers joining two scientists to create an evening-length performance-debate that toured to Harvard University’s Farkas Hall and the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development at Columbia University this fall. The essence of this interdisciplinary project was a product of Nowak’s published research on altruism and evolution. Nowak proposes: “Evolution is not only a fight. Not mere competition. Also cooperation, cooperation is the master architect of evolution. Now that we have reached the limits of our planet, can you cooperate with the future?”

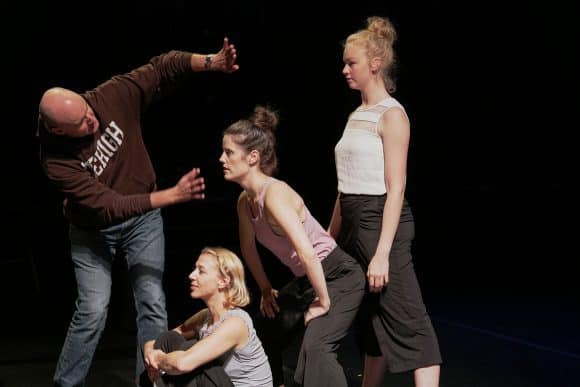

The cast from left to right: Hannah Kickert, Gloria Benedikt, Jessie Jeanne Stinnett, Mimmo Miccolis, Henoch Spinola © Daniel Kruganov

What can I do to contribute to a global effort to create sustainable practices that yield cooperation with the future? Why do I dance and what kind of impact does my dancing have on my environment and myself? As a co-artistic director, entrepreneur, choreographer, and performing artist of the young and fast-growing contemporary dance company Boston Dance Theater (BDT), I am turning to projects that are on the innovative cross-section between the arts, technology, and other disciplines because they have the most potential to have meaningful impact on the level of the creative team, the audience, and beyond. I too, am searching for practices and partnerships for BDT that yield pathways for collective problem solving, or ‘super-cooperation’. As Nowak notes, “[evolutionarily speaking] humans are super-cooperators.”

Overall, Dancing with the Future has revealed to me that scientists, dancers, and policymakers can successfully sit at the same table (or in the same theater or conference hall), tackle the same issues, and productively collaborate toward unearthing sustainable solutions.

We all had to be open to compromises — this is not an easy task in a room full of expert-leaders. I set a mantra for myself to remember that we were creating something completely new. Each time my choreographer-dancer brain sent up a red flag, I chose selectively when to share my opinion with the group. I elected to practice the Buddhist teachings of Shunryu Suzuki, captured poetically in Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.” This choice opened others and myself up to creative and peaceful solutions that I otherwise wouldn’t have seen.

Conversely, I was able to offer constructive solutions at moments when working with the scientific material seemed to overwhelm the studio process, for example, dividing the existing text and music into segments and giving each of those segments a specific choreographic task that related to the content of the scientific text. This was a very simple concept that had to do with pacing and sculpting time. Once we counted out the music, it was easy for us to construct the movement score and see the overall arc of the piece.

Rehearsal with Martin Nowak © Daniel Kruganov

I learned not to be afraid of using my voice and also listening deeply. It was, at first, very intimidating to be seated across from experts in fields outside of my own. I learned that scientists and policymakers can understand, respect, and respond to the decisions I make through a process of peaceful negotiation, even when we speak different languages, were born on different continents, and may have varying political opinions. My fear was ultimately unnecessary because the very nature of this project appeals to the humanity in us all.

This form of cross-disciplinary collaboration allows participants to see our own work in a new light and to discover new languages that are exciting because we have co-authored them. For the work to be successful, the dance, science, and debate components must all have equal weight and value. Otherwise, the movement and its choreographic structure becomes the visual representation of the science rather than an equal partner. When that happens, the magic of innovative collaboration falls flat into familiar territory.

During the process, we often referred to this Chinese proverb: “Tell me, and I’ll forget. Show me, and I’ll remember. Involve me, and I’ll understand.” Dancers understand this concept in a very concrete and visceral way. For scientists, policymakers, or the general audience to understand too, they must be involved as much as possible in the process of what we are doing. If we cannot for reasons of practicality, have them with us in the studio, then we must bring them into the process in another way. It is only by involving them as collaborators that we can generate large scale, super-cooperation.

Sometimes it feels like my dancer colleagues and I exist in a vacuum: we rehearse in the confines of the studio and historically perform on stages that make us appear as ‘other’ from the people we are performing for. Western concert dance has received criticism for being an inaccessible art form and according to the 2016 report from The Boston Foundation, is the most under-funded of Boston’s performing arts. Dancers aren’t typically trained to speak about their work, and often have a hard time receiving criticism. Contemporary dance in particular, can be challenging to general audience members because the language of the art and its conceptual frameworks are sometimes not evident in the work itself — many choreographers feel creatively stifled when asked to explain their work in language and wonder why the art work can’t speak for itself.

I have come to learn that these problems are not unique to dance. After our premiere of Dancing with the Future at Harvard University, scientists thanked me for helping them to understand new meaning within the scientific research presented through my performance. Their experience of live performance elicited a keen sense of empathy that drew them into deeper understanding of the scientific findings. This collaboration yielded a tri-fold, reciprocal impact for the artists, for the scientists, and for the public.

The cast in action © Daniel Kruganov

Our work helped to bridge the traditional gap between creative team and general audience member. It can be that when a member of the public enjoys a performance, they leave the venue with a good feeling and a nice memory as a souvenir. I believe that our art form has the power to do more — to make a greater impact and to be appreciated as an inherent and necessary aspect of our society and culture.

It is our civic responsibility to continue workshopping solutions toward global cooperation and cooperation with future generations. Dancing with the Future has encouraged me, on a micro scale, that this is a reasonable and plausible endeavor. With continued care, attention toward our common goals, compassion, listening, and risk-taking, we can understand one another through the process of creation regardless of what language we speak or where we were born. The next steps may be small, but nonetheless crucial. Next season, Boston Dance Theater will commission new works by three international choreographers with the stipulation that the pieces must speak to pressing global issues, and cross-disciplinary collaboration will be a cornerstone of that production.

Dancing with the Future has revealed to me that partnerships with super-cooperators such the teams at IIASA and Harvard’s Program for Evolutionary Dynamics can bring meaningful potential to catalyze change in me as an individual and in Boston Dance Theater as an organization, while enabling us to reach our extended communities. I can’t wait for the next project!

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.