by Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Strategic board games are staple entertainment for families all over the world, but what many do not know is that games can also be a valuable research tool. As her project for the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), Sara Turner is piloting an experiment that uses a game called the Forest Game, developed by IIASA and the Centre for Systems Solutions, to find out how policy decisions are made and how they change over time. “Games let you abstract from the specifics of a real-world case, but are more human-centric than, for example, computer simulations,” says Turner.

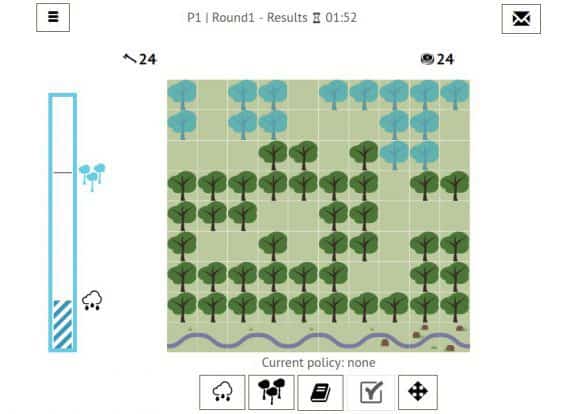

Interface of the Forest Game, © IIASA

In the Forest Game, a group of five to ten players is asked to make decisions about the management of a forest together. Harvesting trees yields returns for the players, while harvesting too many of them might destroy the forest or increase the risk of flooding. There are some uncertainties in the game – for example, the players do not know exactly how resilient the forest is. The goal of the research project is to run multiple iterations of the game with different players and starting conditions, and trace how group discussions and the resulting decisions change over time. This helps to generate hypotheses about the ways in which individuals interact to generate policy outcomes. Each game takes about an hour to play.

Even though the Forest Game deals with forest management, this is only one example of a broader class of decision-making dilemma: when a resource is limited, and it is costly to prevent access, people will tend to over-exploit the resource. This in turn leads to a wide range of problems, from over-fishing to air pollution. Although games cannot capture the complexity of real situations, they can still help us understand the core dynamics of the problem and develop ideas and strategies that are relevant to solving it. “The game is not designed to be directly applicable to real life, but it helps to come up with hypotheses that you can then compare to real-life cases,” explains Turner.

Questions about the sustainable management of resources have been studied for decades, but not a lot is known about the role values play in shaping group decision making and the stability of the implemented policies. To investigate this, each participant is asked to fill out a short ten-minute survey assessing their core values and beliefs, after which they are put into a group with people who either have a very similar or very different worldview from them. “It is really interesting to put a person in a decision-making context with other people and get some insight into how they work through that problem,” says Turner.

© Sara Turner

For example, if you are a person that strongly values equality, in the game you might be likely to argue in favor of a policy where all participants obtain the same amount of returns, regardless of the number of trees the individual player chooses to harvest. If many players in the group share your belief, that policy might be more likely to be implemented than in a very diverse group.

Another interesting question whenever you run a game for research purposes is, “Who are the right players?” Some games are targeted at real-world policymakers, but often games can also be educational for the broader public. ‘’People learn a lot during games, because of the way that information is processed and experienced,” says Turner. That is why many participants, although they might not see a connection between the game and their life at first, find themselves relying on the insights they gained while playing when faced with similar situations in the future.

In this case, the goal is to study group decision-making processes in general, so the details of who is playing are not particularly important. However, to obtain groups of players with heterogeneous worldviews, a high degree of diversity is preferable.

While the game has previously mainly been played by YSSP participants and students of the University of Vienna, Turner is currently trying to recruit a more diverse set of players from both within and outside of IIASA. “It would be ideal to have a pool of participants who come from a wide variety of educational and cultural backgrounds,” she says.

If you are interested in participating in the Forest Game, you can write Sara Turner an e-mail to turner@iiasa.ac.at.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.